Onil Bhattacharyya, MD, and The University of Toronto Health Organization Performance Evaluation (T-HOPE) Team

Contact: Onil Bhattacharyya, MD, onil.bhattacharyya@wchospital.ca

Dr. Onil Bhattacharyya is the Frigon Blau Chair in Family Medicine Research at Women’s College Hospital in the University of Toronto. He practices family medicine and is an Associate Professor in Family and Community Medicine and the Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation.

Abstract

What is the message?

Low and middle income countries (LMICs) face a particularly large burden of mental and behavioral disorders. Four domains of activity by private sector organizations offer potential for both near-term and longer-term impact in improving access to mental health services in LMICs: (1) education programs for health care providers; (2) advocacy/research; (3) interactive on-line platforms; and (4) comprehensive care.

What is the evidence?

The study draws from The Centre for Health Market Innovations (CHMI) database of health programs in LMICs, identifying thirteen programs founded between 1961 and 2011 that focused on mental health. The study collected information on program design from the CHMI database, complemented with other publicly available materials such as program information and annual reports.

Links: Slide

Submitted: October 1, 2016; Accepted after review: January 26, 2017

Cite as: Ilan Shahin, John A. MacDonald, John Ginther, Leigh Hayden, Kathryn Mossman, Himanshu Parikh, Raman Sohal, Anita McGahan, Will Mitchell, and Onil Bhattacharyya. 2017. Innovations in Global Mental Health Practice. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 2, Issue 1.

|

Introduction

The importance of mental health services is rising around the world as the prevalence of infectious disease and other conditions declines. It is estimated that 7.4% of the disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost in the early 2000s is accounted for by mental and behavioral disorders, compared with 5.4% twenty years earlier (Murray, et al. 2012). Unipolar depression, which has seen a 37% increase in burden over 20 years, will be the second-leading cause of DALYs lost in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by 2030 (Mathers & Loncar, 2006). Moreover, measures such as DALYs do not fully capture the burden since much of it falls on family members, causing loss of productive time and stress on care givers.

Addressing mental health must be part of a strategy to address health and well-being because it figures prominently in prioritized health areas such as perinatal health and non-communicable disease. More generally, mental health interventions can improve patients’ economic status, thereby contributing to community development.

Despite the existence of effective and affordable treatments, delivery of services is extremely limited in most LMICs. For example, 76% to 99% of patients with serious mental disorders in Africa are inadequately treated (Faydi et al., 2011). The World Health Organization (2011) report on Human Resources in Global Mental Health estimates treatment rates of mental health disorders in LMICs to be only 30% to 50% due in part to a shortage of 1.18 million health workers.

This article describes innovative efforts among private-sector, non-profit, philanthropic, and public-private partnerships (here-after “private providers”) engaged in providing mental health services in the resource-limited settings of LMICs. We identified striking examples of private providers in several countries that offer initial evidence of opportunities for private models of mental health services to operate as complements to public services.

Two examples provide initial insights.

The Health[E] Foundation uses computer-based courses blended with in-person sessions to provide mental health services in more than a dozen countries in Asia, Africa, South America, and Eastern Europe.

The Anjali non-profit in India partners with the public health system in West Bengal to offer psychiatric and therapeutic services along programs to economically empower and reintegrate patients back into their communities.

We used a database of innovative efforts that address barriers and challenges in mental health services delivery. The Centre for Health Market Innovations (CHMI), managed by the Results for Development Institute, curates an open-access online database of over one thousand organizations in LMICs that catalogues novel approaches to improve health services for the poor.[1] The study draws on this dataset to map the landscape of innovation in mental health services, find evidence in practice at meaningful scale, and review the activities of the organizations in the database that describe a focus on mental health. We identify approaches to the delivery of mental health services that carry the potential to improve patient wellness, have capacity for scalability, and address barriers such as stigma and politicization to sustainability.

We identified 13 mental health organizations for the study. Nine of the 13 are private non-profits; three are public-private partnerships; and one is a for-profit organization. All 13 receive donor funding, while four are also financially supported by government sources and the for-profit venture also receives out-of-pocket payments from its clients.

[1] Available: http://healthmarketinnovations.org/programs.

Accessed 30 September 2012

Study Results

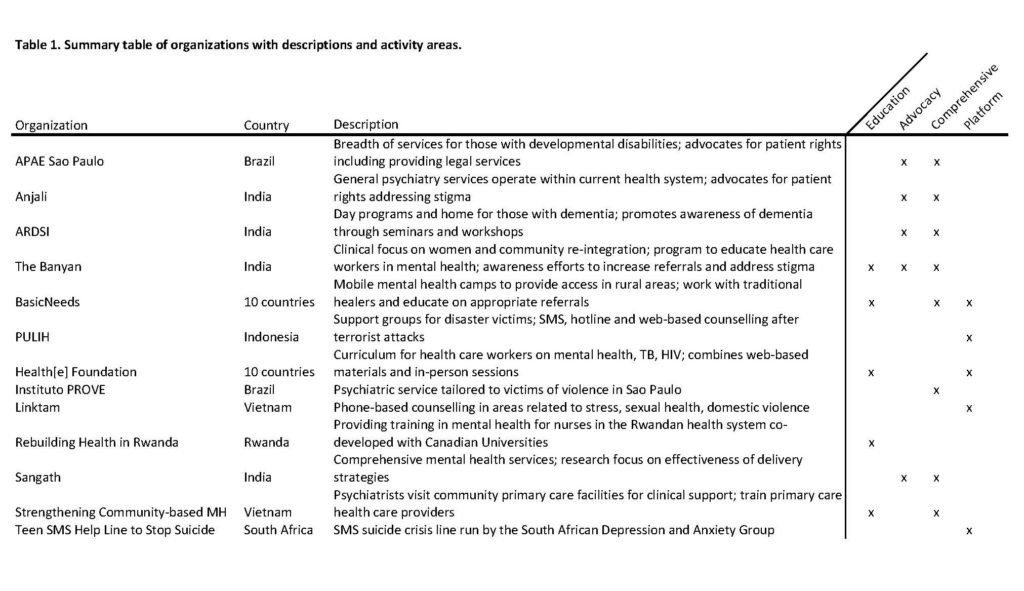

We clustered the organizations based on the activity domains they reported for their mental health services. Four domains of activity emerged from a qualitative analysis of the activities (Table 1): (1) education programs, (2) advocacy and research, (3) novel platforms for patient contact, and (4) comprehensive care.

The clustering procedure assessed the information that the organizations reported about their activities in the CHMI data base, along with information that they reported on their websites. We then aggregated the information into four categories that reflected both discussions in the literature and emergent patterns in the data.

Each of the four activity domains addresses a challenge to the access and availability of mental health services.

- Education programs for health care providers: Several programs offer education on mental health to multiple types of providers, reflecting the point that a lack of trained workers constrains the availability and quality of mental health services.

- Advocacy and research: Several organizations have established formal advocacy efforts and research programs relevant to the clinical context they work in. Some cover a wide range of mental health needs, while others target specific issues such as Alzheimer’s disease or women’s health.

- Novel platforms for patient contact: The availability and accessibility of mental health services can be improved through decentralization from large institutions in urban centres. Several programs have addressed this problem with low- and high-tech platforms.

- Comprehensive care: Current mental health services have left large treatment gaps for some populations. Private-sector organizations are seeking to address these inadequacies through comprehensive whole-person care, often designed for a particular condition.

Most of the 13 organizations engage in more than one of the four activity domains, with average coverage of two domains, but no organization participated in all four domains. Thus, no matter how important the four domains are for addressing mental health needs, no organization appears to have the resources – whether financial or organizational – to attempt to take on the full suite of demands. Instead, each has focused its efforts where it believes it can achieve impact given its resources and missions.

Discussion

Examples of programs in each of the four activity domains help illustrate the opportunities.

1. Education programs for health care providers

Lack of trained workers is a major barrier to improving mental health care. Integration of mental health care into primary care services can improve care delivery, so that education can be clinically effective. In addition, education that provides worker empowerment and experience of increased effectiveness can improve motivation.

Several of the organizations in the study educate health care workers. For instance, among its activities across ten countries in Asia and Africa, BasicNeeds, founded in 1999, engages traditional healers in countries such as Ghana. The approach respects the prominence of these healers in the communities they serve, while addressing the delays in receiving appropriate care. Traditional healers are trained in how to recognize mental illness and to refer to psychiatric services when their own treatments have proven inadequate. Traditional healers also distribute basic household items to patients and their families.

Two other examples stand out. In partnership with the nursing faculties at Canadian universities, Rebuilding Health in Rwanda, founded in 2005, has developed a mental health curriculum that has been integrated into a general nursing training program. Strengthening Community-Based Mental Health, an organization in Vietnam and Angola founded in 2011, uses a similar educational approach while focusing on primary health care workers. Psychiatrists in the Community-Based Mental Health program provide clinical support to primary care providers, seeking to strengthen the ability of the primary-care system to manage mental illness.

These examples show how a community’s capacity to address mental health can be increased by working with both non-medical and medical stakeholders. The approaches aim to engage patients where they come to seek care, rather than attempt to change existing entrenched health-seeking behaviors.

Ideally, the curriculum of national health education programs would include more training in the issues that these private organizations are addressing. However, formal educational programs face limits in both time allocation and institutional constraints in curriculum contents. Hence, there is a meaningful educational role for private sector organizations.

2. Advocacy and research

Many barriers to improved care in mental health can be overcome by political will, especially insufficient funding of services. Challenges to improving funding include fragmented advocacy efforts, the perception that mental health care is not cost effective, and stigma. These challenges undermine the success of programs.

Advocacy must address policy, resource distribution, and funding priorities at the health systems level. One example of this is Anjali (see the “Extended Examples”) in India, an organization that works closely with the public health system in three mental health hospitals in West Bengal. Anjali has positioned itself with a broader clinical mandate within the health system, seeking to drive policy and resource allocation and carry out focused research on epidemiology. The partnership relationships allow Anjali to deliver services efficiently, while also allowing them to participate in health policy development through advocacy rooted in a rights-based framework.

Other examples of advocacy stand out. APOE Sao Paulo has engaged in advocacy efforts at the legislative level in Brazil, since 1961. In 2010, there were 30 legislative proposals at the state level and 24 at the municipal level pertaining to the rights of those living with disabilities. These are the results of collaborative efforts with other concerned organizations. In India, meanwhile, the Alzheimer’s and Related Disorders Society of India (ARDSI), founded in 1993, promotes improvement of programs directed at Alzheimer’s disease.

Some organizations also contribute to the systematic research base on mental health. Only 3% to 6% of articles on mental health in high-impact journals are from LMICs (Eaton et al., 2011; Razzouk et al., 2010). Hence, we need substantially more knowledge of challenges and practices in multiple LMIC contexts.

Sangath, founded in India in 1996, delivers a broad slate of mental health services through traditional and non-traditional workers while also linking services with research on epidemiology and the testing of delivery models. The organization has over 23 peer-reviewed publications. Sangath tests interventions such as using lay health workers through rigorous designs, describe the patient experience in LMICs with qualitative studies, describe outcomes for patients using observational designs, and make the case for addressing mental health internationally in journals such as The Lancet.

Sangath’s research efforts capture knowledge gained from extensive experience in delivering care and translate it effectively to other care providers through a credible process. This experience shows how rigorous research on models of care can be carried out in low-resource settings, identifying key mechanisms and highlighting effective ways of improving clinical practice in mental health.

The Banyan, which is an Indian organization founded in 1993 that cares for wandering women in Chennai, offers an example of advocacy and research, seeking to engage the community in order to increase awareness and reduce stigma. Banyan’s range of services now includes outpatient psychiatric care for 470 patients per month, as well as providing homes to help with the rehabilitation and community reintegration of 180 patients at any given time.

Recognizing the need for advocacy and research to identify best practices and barriers to improve care, the organization founded the Banyan Academy for Leadership in Mental Health. Its research is focused on the effect of social determinants of health on those with mental illness and its activities help empower various stakeholders to affect policy and promote access to care. Training seminars and courses address grassroots awareness of mental health issues and demand for mental health care.

The key point is that organizations like these that have been successful in delivering care have the potential to disseminate their knowledge to improve services beyond the scale and clinical reach of the focal organization. These advocacy and research activities help to develop effective policy and health planning, and improve access to mental health services for those in need.

3. Online platforms

Online platforms based on phones, SMS, and the web offer substantial potential benefits for mental health services. Immediate counselling is an obvious target. For instance, e-Counseling PULIH (Indonesia), LinkTam (Vietnam), and Teen SMS Help Line to Stop Suicide (South Africa) use the web, phone, and SMS to provide counseling services. On-line platforms such as in these examples offer desirable options when confidentiality, geography, and/or cost are barriers to client access.

Some platform innovations also support educational and training activity. Health[e] Foundation (see the “Extended Examples”) is an innovative education program that trains health care workers in multiple countries in Asia, Africa, and South America via an online platform, in conjunction with face-to-face training sessions. BasicNeeds, meanwhile, uses mobile mental health camps to provide access to psychiatrists, therapists, and medications to rural communities in multiple countries.

4. Comprehensive care of mental health needs

Several programs illustrate approaches to providing comprehensive care that addresses ongoing mental health needs, rather than attempting to deal with individual incidents that flare up into long term problems.

Instituto Prove was founded in 2008 by a psychiatrist and professor at the School of Medicine of the Federal University of São Paulo. The institute offers free psychiatric treatment to victims of violence in São Paulo, Brazil. The Brazilian public healthcare system does not specifically target violence victims. The Institute treats people who witnessed or were victims of violence. Treatment includes targeted and specific psychotherapy sessions, as well as antidepressant and antianxiety medicines. The institute is supported by the university and also receives funding from Instituto Rukha in Brazil and private donors.

Comprehensive care programs work both independently and in partnership with public facilities. Instituto Prove and The Banyan, which we described above, are examples of specialized facilities. The Anjali example that we described earlier, by contrast, operates within state hospitals, seeking to leverage available resources and encourage the state to engage with its responsibility towards mental health.

No one of the comprehensive care programs is a full solution. Nonetheless, they offer models for expanding the availability of care. Indeed, eight of the 13 organizations in the study address elements of comprehensive care, typically in combination with activities in other activity domains. Moreover, the gains from the other three domains – education, advocacy, and on-line platforms – can help generate systemic changes that provide the basis for additional longer-term advances in comprehensive care.

Two Extended Examples

Health[e] Foundation

The Health[e] Foundation demonstrates how online platforms can be used to educate health care workers at an unprecedented scale across multiple clinical areas and in many countries.

Health[e] Foundation was launched in 2006 as a not-for-profit dedicated to supporting nascent health care systems through the education of its health care workers. Initially developed as an HIV curriculum, the organization has expanded to include dozens of modules spanning areas such as mental health, child health and communicable diseases. The organization now operates in more than a dozen countries in Asia, Africa, South America, and Eastern Europe.

The foundation’s courses bring knowledge of best practices in care to resource poor settings using computer-based courses blended with in-person sessions. Using this platform allows for easy implementation and uptake in new settings but also allows for expansion to cover other health areas as they have so successfully done thus far. By 2014, 4,600 health care workers had been trained since inception. In 2011, ten courses were given to 867 trainees in nine countries. The budget for 2012 was under €700,000.

Anjali

Anjali demonstrates that private partnerships with resource-challenged public health systems in LMICs can improve access to services, reduce costs and affect policy through effective, collaborative advocacy efforts.

Anjali is a not-for-profit based in West Bengal, founded in 2008, with a strong dedication to advocacy. It offers a breadth of psychiatric and therapeutic services as well as programs to economically empower and socially reintegrate patients back into their communities.

Anjali operates within the public health system at three mental hospitals. This relationship increases access and also reduces costs. For instance, Anjali is able to offer rehabilitation in half-way homes at a cost of $870 per year, less than half the community average.

In India, less than one percent of health expenditures are earmarked for mental health, so the organization uses its relationship with the government to advocate for the mentally ill and put their priorities and rights on the policy agenda. They have described their relationship with the government as “a fine balance of confrontation and support”.

Conclusion

Near-term benefits in achieving impact in mental health services in LMICs can arise in each of the four activity domains. Education and advocacy both have potential for high impact beyond the life or reach of a single organization, helping to raise all boats. On-line platforms based on phone or web technology, whether to provide client services and/or in support of education programs, meanwhile, have substantial potential for immediate impact. Comprehensive care has immediate impact for the target clients, while providing models for similar programs.

Activities in the four domains also interact to contribute to longer term gains. The organizations we studied commonly have found ways to engage education and advocacy within existing channels of care to deliver mental health services. This is being done with both traditional healers and primary care providers. Education can also be carried out using online platforms, leading to rapid expansion to train thousands of health care workers in multiple countries.

Advocacy can be done either embedded within or outside the public health system, such as through community awareness programs aimed at reducing stigma or through legislation in pursuit of recognizing the rights of those with mental illness. Ongoing research can support advocacy, strengthening the case for making mental health a priority in development policy at local and global levels, all the while improving clinical care through thoughtful knowledge translation. Moreover, advances in health systems and related infrastructure that stem from education, advocacy, and platform innovation are likely to improve the long-term landscape for comprehensive care.

A key issue in any of the activity domains is program sustainability. All initiatives included in the study received at least part of their revenue from donor funding, which creates challenges for ongoing renewal. Nonetheless, most of the organizations in the study have operated for many years, with the oldest being founded in 1961 and a median founding year of 2000. Hence, these organizations, at least, have succeeded in meeting the pressure to maintain donor support.

One limit to the study concerns assessing the impact that the organizations have achieved. It is difficult to determine systematic outcomes of interventions of this nature because they are upstream, making measurement of relevant indicators challenging and forcing the attribution of downstream causality to be less direct. There is some evidence of programs achieving notable outputs, but a lack of evidence quantifying health impact. T-HOPE (2015) suggests a set of metrics that provides a feasible, credible, and comparable approach to measuring impact.

In addition, we must improve our understanding of the organizational characteristics and activities that are associated with scale. The organizations in the CHMI-derived subset are all private, with some working in close partnership with government sources. Further work should determine patients’ health seeking behaviors and attitudes towards private providers and to what extent this overcomes traditional barriers to accessing psychiatric care such as stigma.

This article has identified potentially promising programs that could serve as templates for addressing mental health services in LMICs. Rigorous measurement of these activities focusing on efficiency, quality, and scale will help identify the most promising approaches for support or replication by governments, donors or others.

Authors

[1] Ilan Shahin, MD, MBA (Research Associate, Women’s College Hospital, University of Toronto); John A. MacDonald, MD (MBA Candidate, MIT Sloan School of Management); John Ginther, MBA (Research Associate, Toronto Health Organization Performance Evaluation, (T-HOPE), University of Toronto); Leigh Hayden, PhD (Research Coordinator, North York General Hospital); Kathryn Mossman, PhD (Research Coordinator, Women’s College Hospital); Himanshu Parikh, MD, MSC (Study Delivery Leader, AstraZeneca Canada Inc); Raman Sohal, MBA, MA (PhD Candidate, Institute of Health Policy Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto); Anita McGahan, PhD (Rotman Chair in Management, Professor of Strategic Management, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto); Will Mitchell, PhD (Anthony S. Fell Chair in New Technologies and Commercialization, Professor of Strategic Management, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto); Onil Bhattacharyya, PhD, MD (Frigon Blau Chair in Family Medicine Research, Women’s College Hospital; Associate Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto).

References

Center for Health Market Innovations (CHMI). 2016. Available: http://healthmarketinnovations.org/programs. Accessed 30 September 2012.

Eaton J, McCay L, Semrau M, Chatterjee S, Baingana F, Araya R, Ntulo C, Thornicroft G, Saxena S. 2011. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 378: 1592-1603.

Faydi E, Funk M, Kleintjes S, Ofori-Atta A, Ssbunnya J, Mwanza J, Kim C, Flisher A. 2011. An assessment of mental health policy in Ghana, South Africa, Uganda, and Zambia. Health Research Policy and Systems, 9: 17.

Murray CJL, et al. 2012. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 380: 2197-2223.

T-HOPE. December 2015. Assessing health program performance in low- and middle-income countries: Building a feasible, credible, and comprehensive framework, Globalization and Health.

http://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-015-0137-5; DOI: 10.1186/s12992-015-0137-5

World Health Organization. 2011. Human resources for mental health: workforce shortages in low- and middle-income countries. Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501019_eng.pdf. Accessed 4 October 2012.

Mathers CD, Loncar D. 2006. Projections of Global Mortality and Burden of Disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med, 3(11) :e442.

About T-Hope

Toronto Health Organization Performance Evaluation (T-HOPE) includes a diverse group of medical, management, and social science experts based at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management and Department of Family and Community Medicine. This interdisciplinary research team combines health and management experience and expertise with the aim of connecting theory to practice in the field of global health innovation and performance.

Bringing together MBA students and medical residents to solve real world global heath challenges, the research group is led by Dr. Onil Bhattacharyya, Frigon-Blau Chair in Family Medicine Research at Women’s College Hospital and Associate Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto, as well as Dr. Anita McGahan, Rotman Chair in Management, Professor of Strategic Management, at the Rotman School and Dr. Will Mitchell, Anthony S. Fell Professor of New Technologies and Commercialization, Professor of Strategic Management at the Rotman School.

By engaging in rigorous and responsive research, the team strives to improve performance reporting of innovative health programs, understand and promote the scale up and sustainability of high-impact health initiatives, and identify successful innovations for improved health quality and access in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

[1] Authors: Ilan Shahin, MD (Resident Physician, Dept. of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto); John A. MacDonald, MD (Resident Physician, Department of Family Medicine, University of Toronto); John Ginther, MBA (Research Associate, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute and Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto); Leigh Hayden, PhD (Research Manager, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto); Kathryn Mossman, PhD (Research Coordinator, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto); Himanshu Parikh (Master’s Student Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto); Raman Sohal, MBA (Research Associate, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute and Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto); Anita McGahan, PhD (Rotman Chair in Management, Professor of Strategic Management, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto); Will Mitchell, PhD (Anthony S. Fell Chair in New Technologies and Commercialization, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto); Onil Bhattacharyya, PhD, MD (Clinician Scientist, Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital; Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Toronto)

[2] Available: http://healthmarketinnovations.org/programs.

Accessed 30 September 2012