Michael Lefferts, Tina Liu, and Jonathan Friedlander, Harvard Business School

This article is based on the winning presentation of the Business Alliance of Healthcare Management MBA Case Competition in Berkeley, California, March 2017.

Abstract

What is the message?

Oscar Health Insurance, a 2012 medical insurance start-up in the U.S., faces an uncertain future due to ambiguity in national healthcare reform. Scenario planning tools help create road-maps to deal with multiple futures.

What is the evidence?

Analysis based on scenario planning tools.

Links: Exhibits

Submitted: July 10, 2017; Accepted after review: August 8, 2017

Cite as: Michael Lefferts, Tina Liu, and Jonathan Friedlander. 2017. Scenario Planning Tools For Organizations Struggling With Healthcare Reform Uncertainty – The Case Of Oscar Health Insurance. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 2, Issue 2.

Uncertainty Is Ubiquitous

“The only certainty is that nothing is certain.”

-Pliny the Elder

Strategic planning for organizations is always a challenge. Without knowing how the future will unfold, committing limited resources can spell disaster. At the moment, strategic planning for healthcare organizations may seem impossible. As the Republican caucuses in Congress have undertaken the task of healthcare reform, many healthcare organizations fear the outcome could pose an existential threat. In fact, the uncertainty itself has been paralyzing for health insurers that have been reluctant to bid on exchange plans because they cannot accurately price premiums without more foresight into how regulations will evolve or have raised rates precipitously because they fear the future.

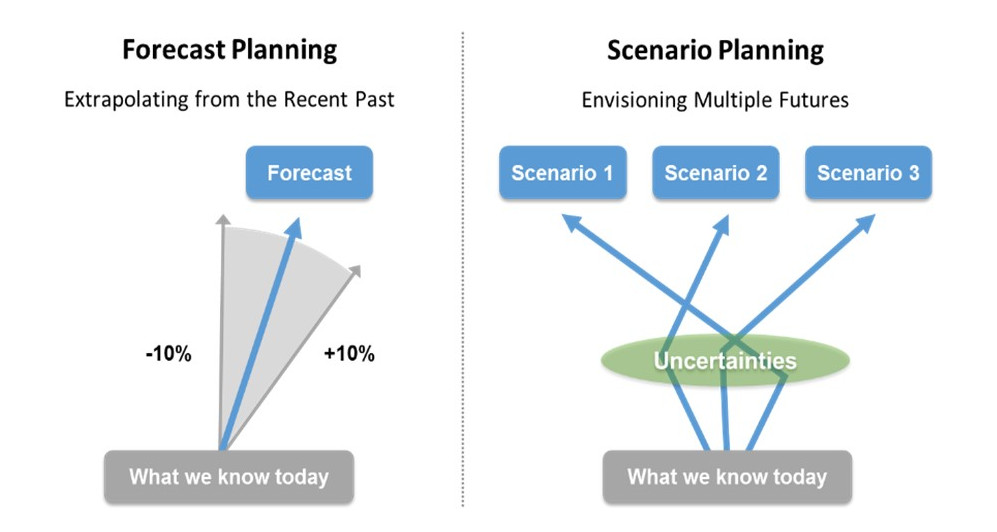

Scenario planning is a strategic tool that has been developed specifically to address these moments of paralyzing uncertainty. Unlike forecasting, which focuses primarily on projecting trends into the future with reasonable tolerance, scenario planning focuses on the most critical uncertainties an organization faces (see Figure A). The process of scenario planning was developed for military and corporate applications—most notably by Royal Dutch/Shell in the 1970s, one of the only oil companies that was able to anticipate and respond strategically to the oil embargo of 1973 (1). While scenario planning will not be able to predict the outcome of healthcare reform, it is a tool to help consider a wide range of possible futures and allow healthcare organizations to begin preparing now for whatever the future actually holds.

Figure A: Forecast Planning vs Scenario Planning (2)

In March 2017, the authors of this article prepared a case on Oscar Health Insurance, a medical insurance start-up founded in 2012, for the 2016-2017 Business School Alliance for Health Management (BAHM) case competition at the Haas School of Business at the University of California Berkeley. The competition’s challenge was to provide recommendations for a major healthcare organization in light of the uncertainty of health reform. We undertook a scenarios-based strategic planning approach from the perspective of Oscar’s management team in order to understand the implications of healthcare reform for Oscar and to develop recommendations for how Oscar could begin preparing to respond to the potentially existential threat that a repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) posed.

The scenario process starts by evaluating what is known – such as current regulations, proposals from both houses of Congress, and the President – and then introducing different potential outcomes for various things that are still uncertain, such as the form of insurance subsidies / tax credits, and timing of reforms. This approach provided us with several scenarios that organizations could encounter in coming months and years.

The following discussion describes the scenarios we developed in March 2017 based on the events around health reform at the time. While more recent developments since then are not reflected, the arc of these scenarios is still valid and useful as an illustration of the scenario planning approach for developing corporate strategy.

Case Study (March 2017): Scenario Planning For Oscar Health Insurance

Overview

The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) spurred the launch of state-run Health Insurance Exchanges (HIX) and with them several new innovative insurers. Oscar Health Insurance is among the most visible—founded in 2012, Oscar quickly captured the imagination of the industry and reached a $2.7 billion valuation in its latest round of venture funding in early 2016 (3). Despite the headwinds facing the individual HIX market, including fewer-than-expected enrollees, fewer-than-expected employers dropping coverage, and difficulties in pricing risk, Oscar has enrolled over 145,000 individuals across New York, California, and Texas and has captured over 20% market share on the New York City exchange (4). With a simple user-interface, free access to staff physicians by phone, a concierge team assigned to each member, and wearable-enabled monetary incentives, Oscar has changed the way individuals perceive their health plan.

Despite success “delighting” its members, Oscar has struggled to become profitable and has been forced to exit two markets (Dallas and New Jersey) (4). Now, with the ACA under assault by the new Republican administration, Oscar’s very raison d’être could disappear. Oscar itself has recognized that healthcare reform represents an existential threat to the individual marketplace and has already taken one defensive step by entering the small-group market in New York this February. While some industry observers question whether this will be enough to help Oscar survive the repeal-and-replace efforts should they re-emerge in Congress, there are many scenarios for legislation that could present opportunities for Oscar if it is agile enough to capitalize on them.

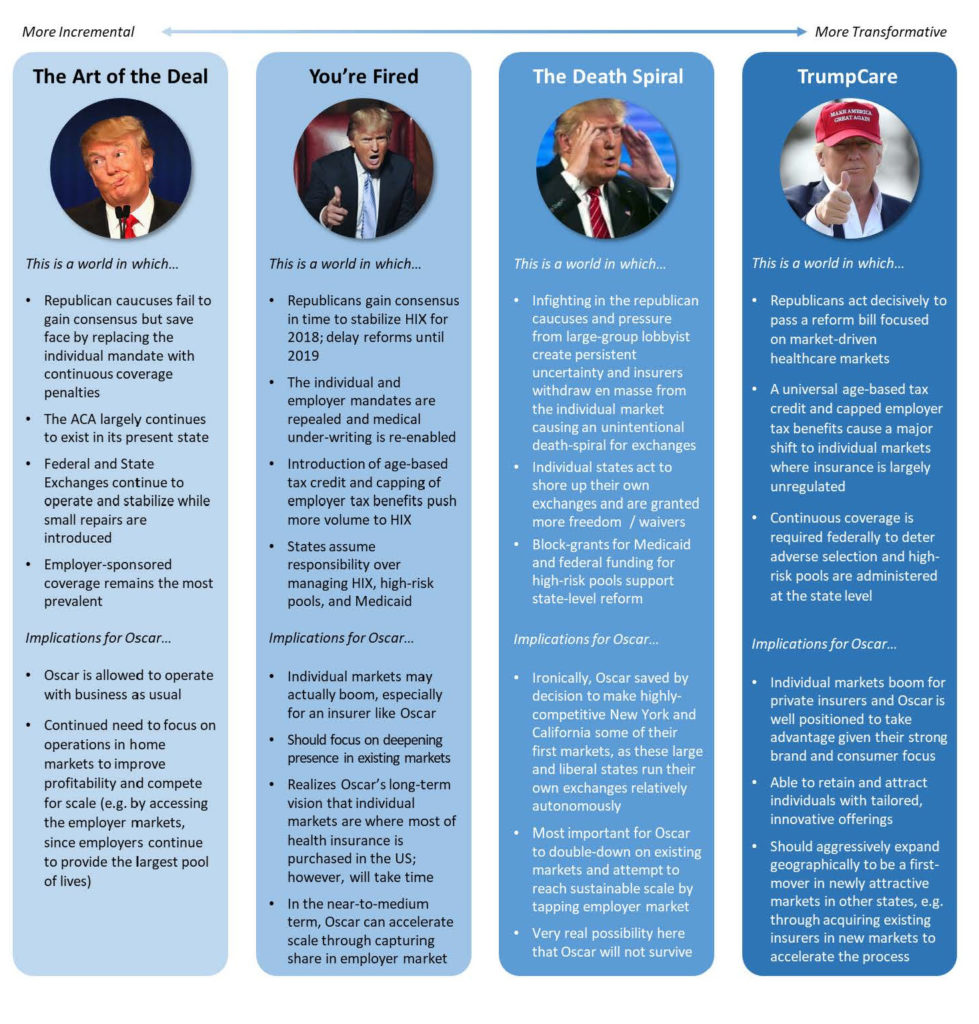

Given the continuing uncertainty surrounding reform efforts – Figure B summarizes the critical policy uncertainties relevant for Oscar – we have mapped out a range of possible scenarios and evaluated the implications for Oscar across this spectrum of potential futures. Figure C outlines the four scenarios, which exist on a continuum spanning moderate incremental “repairs” to wholesale repeal-and-replace legislation that moves the U.S. to a market-driven individual insurance marketplace. In every scenario, Oscar would benefit from limiting its geographic expansion and instead driving scale by further penetrating existing markets. In three out of four scenarios, we find that Oscar can and should supplement its deepening strategy by entering the employer-based coverage market by focusing on mid-size companies.

Oscar Health Background

Oscar Health was founded in 2012 by Harvard Business School classmates Mario Schlosser, Kevin Nazemi, and Josh Kushner to take advantage of the new opportunities anticipated to be created by the ACA. The company focused on offering individual plans, both directly and through health insurance marketplaces. It branded itself as a modern-era company offering a far simpler, more consumer-friendly experience to plan members. Exhibit 1 summarizes Oscar’s value proposition to customers. For example, members are assigned a four-person concierge team consisting of a nurse and three aides trained in navigating the health care system, who have access to the patient’s medical history and who can locate an in-network specialist and even set up the appointment. Members also have free access to video-conference consultations with Oscar-employed doctors who can provide medical advice, write prescriptions, or triage to an in-person visit (Exhibit 2 summarizes Oscar’s telemedicine services. Consumer marketing campaigns on platforms like the NYC subway and on TV have reinforced Oscar’s brand image among its target audience – Exhibit 3 provides an example of Oscar ads.

Oscar was inspired by personal frustration with an explanation of benefits received from a health insurance company. The new company subsequently launched its insurance business in New York City in 2014, hoping to ride the new market created by the ACA health insurance exchanges. In its first year, Oscar attracted 16,000 members and generated revenue of $72 million (5). In the following year, Oscar expanded coverage to New Jersey and grew to 40,000 members, with revenue of $180 million and the average subscriber paying annual fees of $4,500. In 2016, the company expanded further into Southern California (Los Angeles, Orange County) and Texas (San Antonio, Dallas), rising to 135,000 members with about half in New York. In 2017, consistent with other exchange participants, Oscar raised its exchange rates by about 20%; in that same year, the company entered Northern California while exiting New Jersey and Dallas (6). According to Schlosser, a quarter Oscar members have been sourced through exchanges, while three-quarters purchased plans directly through Oscar’s website, with one third of members hearing of Oscar via word-of-mouth. Oscar currently commands about 20% market share in New York City on the individual exchange (4).

Oscar’s premium price point ($50-$60 per member per month (PMPM) above the cheapest plan in the New York market) and tech-focused benefits attract a younger, millennial-heavy member population –average age of 39, with the highest-volume age bracket being 26-35 (4). According to traditional insurer wisdom, this customer segment is attractive, as they are less likely to be sick and thus less expensive to insure than older, more chronically ill patients.

Nevertheless, Oscar’s business is highly capital intensive. Health insurance companies compete on scale, as large customer bases allow insurers to negotiate lower provider rates and/or offer a wide provider network, which helps attract yet more customers in a reinforcing cycle. To start the flywheel of attracting customers, Oscar must suffer large losses for years before it is able to attain sustainable scale. In 2015, Oscar reportedly lost about $100 million (7); its 2016 minimum-loss-ratio (the portion of premiums that it spends on providing medical care) was 115%, indicating significant unprofitability (4).

Additionally, beyond the traditional struggles of a new insurer, Oscar has suffered pains similar to other participants on the newly created and less-than-ideally-oiled individual exchanges: fewer-than-expected enrollees (12 million sign-ups in 2016) and fewer-than-expected employers dropping coverage. According to Schlosser, the government owes the company about $200M for backstop insurance that the government had promised to exchange participants to entice initial entry (4).

Despite the market challenges, Oscar has continued to invest in developing its business operations. The company initially rented its New York provider network from MagnaCare, but has transitioned over time to its own narrow networks (8). Beginning 2017, Oscar members were restricted to only the providers that Oscar has negotiated to participate in its limited network; in New York, that includes Mt. Sinai Health System, Montefiore, and Long Island Health Network (5). Schlosser has indicated that these providers were particularly strong partners for Oscar’s data-driven, highly integrated care management approach and are typically at risk, thus aligning incentives between insurer and provider (4).

Oscar has also begun experimenting with its business model, diverging from the classic insurer in December 2016 through opening its own dedicated clinic in New York, in collaboration with Mount Sinai Health System, offering primary care and wellness to members(5). Beginning in February 2017, Oscar expanded beyond the individual market into small groups (companies with fewer than 100 employees) in New York(5). Their stated goal is to eventually serve medium-sized companies(5).

The company maintains that while it took advantage of the ACA exchanges to enable lift-off, it can now power ahead regardless of exchange developments. The company is still significantly funded, having raised $750 million in total from Thrive Capital, General Catalyst, Khosla Ventures, and others. Oscar’s most recent round of investments in 2016 valued the company at $2.7 billion (3).

Critical Uncertainties: Many Different Proposed Policies

While President Trump proposed seven planks to reform healthcare legislation in a policy brief during his campaign (summary list provided in Exhibit 4)(9), he and his chief healthcare deputy Tom Price went “all in on” the House Republican’s February 16th plan (10). The plan has elements of all the major Republican plans proposed to date but differs from both Paul Ryan and Tom Price’s previous plans in important ways. For example, the House’s proposal suggests repealing the individual mandate, something neither Ryan nor Price’s plans proposed (see Exhibit 5 for a summary of all major Republican proposals). The Senate Republicans subsequently released multiple proposals – those proposals failed in July 2017, though may yet reemerge in some uncertain form, whether as legislation or executive action outside the legislative system.

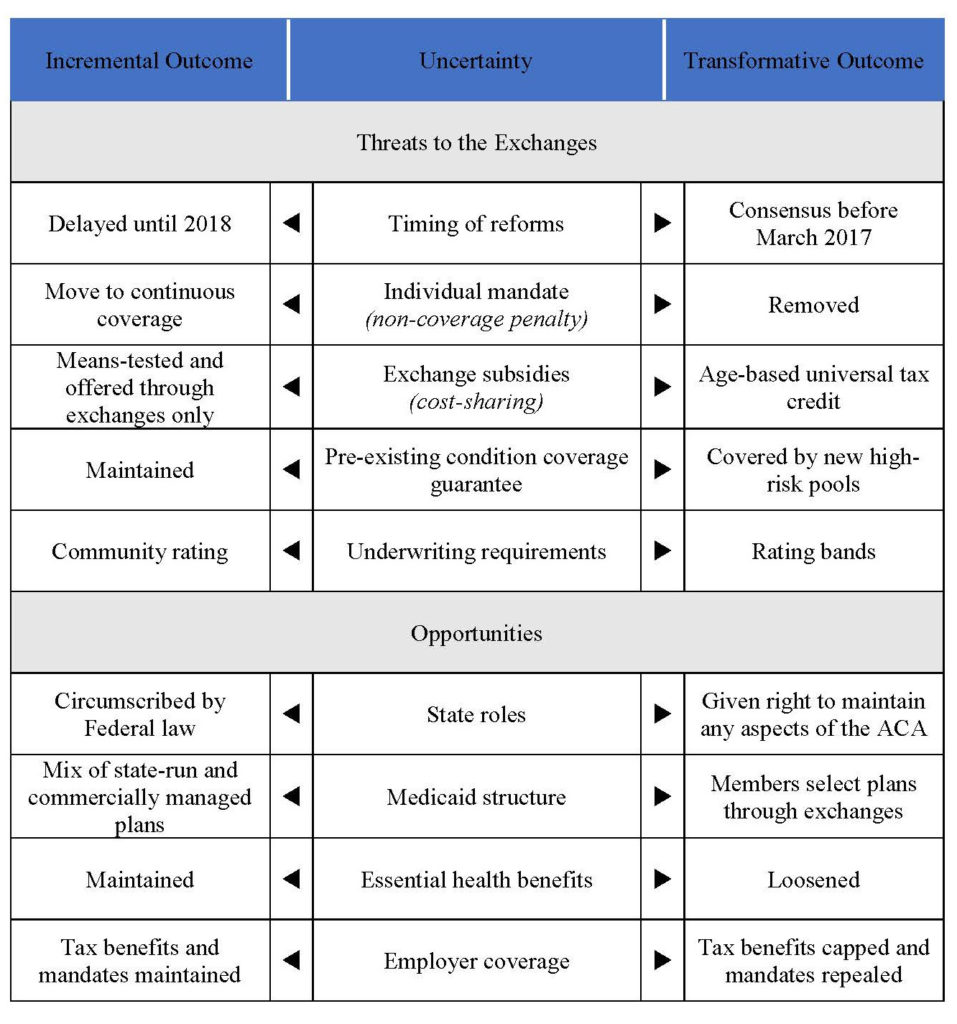

Rather than predicting the exact outcome of every proposal, we have outlined key policies that have been put on the table and outlined the two ends of the range of possible outcomes based on recent proposals. We’ve further narrowed the list of uncertainties that are most critical for Oscar Health. For example, while there is uncertainty around the health savings account (HSA) contribution limit and what new items may be covered, this uncertainty is more “incremental” than “critical” for Oscar in particular. To be considered “critical”, the uncertainty would have to pose a major (perhaps existential) threat or opportunity for Oscar (see Figure B for a complete list).

The timing of the possible reform is among the most important uncertainty facing Oscar and other stakeholders in the industry. Timing is particularly important for state governments that will have to undertake their budget planning process in the coming months and insurers on the government exchanges that had to bid for plans starting in March. Without more clarity on the form and timing of policy, state governments may not be prepared for the budgetary consequences of reforms (e.g., maintaining exchanges and subsidies, reforming Medicaid under capitated model) and insurers may not submit bids on the exchanges due to inability to underwrite lives without understanding how the individual insurance marketplace will change (e.g., rules for rating premiums, pre-existing condition coverage guarantee, individual mandate). Already many larger insurers, including Humana, Aetna, Anthem, Cigna and Humana, have publicly stated they will likely retreat from individual exchanges. (11,12)

While larger insurers currently have a limited presence on the exchange, a shift to universal tax deductibility and capping tax benefits to employers that offer group coverage could cause these large plans to re-evaluate the need to participate in the individual markets. Likewise, smaller insurers such as Oscar may have to take a major bet on how to best underwrite risk that will cost them significant profits if their predictions turn out wrong. Notably, smaller insurers have the fewest financial resources to weather an actuarial miss.

As such, even without additional certainty around the timing and form of legislation, it is possible that the individual exchanges and state-run Medicaid programs in their current form may collapse regardless of the eventual form of policy changes. Through the Internal Revenue Serices and Health and Human Services department, the administration attempted to project some certainty before reforms were implemented but it is still unclear whether it will be enough to keep the exchanges from collapsing (13). That said, some of the certainty they are suggesting—for example, not enforcing penalties that the ACA imposed on people who did not purchase coverage—could ultimately destabilize the exchanges.

Together, timing and other policy changes pose an existential threat to individual exchanges such as Oscar. That said, there are potential opportunities for Oscar to do well depending on the outcome of regulations if the individual market were to expand and the role of employers in sponsoring group coverage were to diminish. A potential move to age-based universal tax credits and away from means-tested exchange subsidies potentially broadens the pool of individuals shopping for insurance as does capping the tax benefits that employers receive for providing group coverage. Likewise, providing Medicaid enrollees more freedom to choose commercial individual coverage could present an opportunity to enroll more lives for Oscar. The outcomes of premium rating rules could also allow Oscar to price plans more cheaply for its target demographic—young, healthy millennials.

Figure B summarizes the critical uncertainties and their range of outcomes. Combining outcomes from these uncertainties will help us construct a range of scenarios Oscar may face.

Figure B: Critical Policy Uncertainties for Oscar Healthcare (14)

Scenarios: The Spectrum of Possible Futures Confronting Oscar

Using the critical uncertainties detailed above, we conducted a half-day scenarios workshop to create a range of possible scenarios that represent the full spectrum of possible outcomes given the degree of uncertainty surrounding reform (see Figure C below). The scenarios represent narratives on how policy could evolve beyond the conventional wisdom (if there is any at this time).

Figure C: Summary of Scenarios[1]

[1] Result of half-day scenarios workshop.

Common Strategies

While Oscar’s operating environment varies significantly across the four scenarios described above, four recommendations hold true.

Focus on key geographies: First, since a health insurer’s ability to reach profitability depends in large part on its ability to reach scale, we would advise Oscar to focus on only a few key geographies and continue going deep within them, as opposed to rapidly expanding across several geographies. The latter may be attractive given the relative newness of the individual insurance markets and thus the first-mover advantages that would seem to exist. However, several factors test the wisdom of this rapid geographical expansion. Plans must re-bid for participation and members must re-select their plans every year, reducing the stickiness of any given plan. Additionally, since provider dynamics and regulatory requirements vary significantly across states, Oscar’s experience in any given state may not be relevant for entry into other states, thus reducing the ease of geographical expansion. Most importantly, since scale is the lifeblood of an insurer, Oscar’s survival depends on achieving it in its existing homes; this needs to be the company’s first priority.

Employer market: Our second universal recommendation to Oscar is to develop a product in the employer market to widen the funnel of members it can feed into its provider network. Although we believe Oscar’s vision that all Americans will eventually live on individual exchanges may prove true in the far future, the vast majority of private health insurance today is still offered through employers. Oscar needs to tap this reservoir of members if it will achieve the scale it needs to survive to the day where individual markets rule.

The company is just beginning to penetrate employers through the small group insurance market, which we view as wise given its adjacency to the individual market. If this market were to go away under future reform, however, we think Oscar’s best approach to serving medium and large employers will have to be through partnering with existing administrative services only organizations (ASOs) that already offer the broad provider network these employers require. Oscar will need to leverage its high-tech, service-oriented front-end as the asset of value to trade in this relationship. Understanding the partner’s willingness to integrate and truly collaborate will be critical to Oscar’s success in this approach. As such, we recommend a joint-venture structure to help align incentives. Health Care Service Corporation may be a willing first partner as it is fragmented by state and small-scale pilots could be conducted selectively. Likewise, there is the opportunity in some geographies to be a value-added partner and maintain a visible brand.

Another possible point of entry into the employer-sponsored space, could be through participation on private health exchanges such as Liazon or Aon Hewitt that offer group plans. Oscar is already sold through private exchanges serving individuals like Health Sherpa so has some experience in this channel but would need to adapt its offering for the group-plan space. The biggest challenge may be identifying an exchange that serves employers that are geographically limited to the markets where Oscar already has a provider network.

Medicaid: Third, Medicaid is the most likely insurance program to see significant changes in the next round of healthcare reform and many of the scenarios envision a future in which Medicaid beneficiaries are given a subsidy to purchase insurance on individual exchanges. Individual states will potentially have substantial discretion with Medicaid and Oscar’s current home base of New York will be among the states most likely to maintain current benefits and program administration. That said, as Oscar gains scale, it should consider how it might be able to use its data-driven narrow networks and high-touch concierge team to profitably insure Medicaid beneficiaries. While many insurers avoid this market because the spend is high and reimbursement is low, the high-touch concierge model is successfully being innovated in low-income communities by providers like Oak Street Health that manage Medicare beneficiaries and dual-eligibles (15).

Exit options: Our fourth recommendation for Oscar is to consider the worst case world of exit options. Starting a new health insurance company was always a high risk, asset intensive endeavor. If the regulatory environment truly turns hostile, Oscar’s survival as a full health insurance company is under certain threat. Its alternatives may consist of selling to a larger company or pivoting to an ASO model so the company is no longer at risk. While not the original vision of the founders, the continued availability of Oscar’s services to members still represents a lot of value created.

Conclusion

“Plans are nothing; Planning is everything.”

-Dwight D. Eisenhower

While these scenarios were developed before March 2017 (well before the House bill passed and before the failure of the Senate’s proposed legislation in July), they are still very much relevant for Oscar and provide, at a high level, a broad range of possible outcomes for continuing reform. The implications of “The Art of the Deal” and “The Death Spiral” scenarios both stand in large part, even if some of the underlying uncertainties have shifted (e.g., repeal of the individual mandate seems unlikely). While scenario planning should be an iterative process, robust scenarios should provide a wide enough range of likely futures that they provide lasting insights. More than anything, the scenarios-based process demonstrates that organizations, even faced with paralyzing uncertainty, can take steps to begin preparing for the future. In fact, merely understanding the implications in various scenarios will allow an organization to more proactively respond than had they made an incorrect forecast or done nothing at all.

In the case of Oscar, we discovered that healthcare reform offered as many opportunities as threats. Major changes to undermine the individual markets could pose an existential threat; however, in all scenarios the HIXs in Oscar’s select home markets should survive and may even expand. This continues to be true even now. More recent discussions of bipartisan legislation to repair elements of the ACA was even accounted for as a possibility in the “The Art of the Deal.” Repairs could ultimately help Oscar’s profitability by changing the competitive dynamics in the marketplace or allowing Oscar to make small changes to capture more profitable, risk-adjusted members. Any substantive changes to employer-sponsored care through reform of tax policy could also prove a boon to the individual market that Oscar would be well-positioned to capture.

Healthcare organizations would do well to embrace scenario planning in the current context of critical uncertainty. For many, it could mean the difference between survival and extinction and for others it could help them spot opportunities that propel them to future success. For Oscar, it is too soon to tell how it will fare, but there are steps they can begin taking now to prepare for an uncertain future.

References

- Scearce D, Fulton K. What If? The Art of Scenario Thinking for Nonprofits. Global Business Network. 2004.

- Global Business Network.

- Bertoni S. Oscar Health Gets $400 Million and A $2.7 Billion Valuation from Fidelity. Forbes. 2016 Feb 22.

- Schlosser M. Presentation at Harvard Business School. 2017.

- Levy S. Oscar Is Disrupting Health Care in a Hurricane. Backchannel. 2017 Jan 5.

- Abelson R. Health Insurer Hoped to Disrupt the Industry, but Struggles in State Marketplaces. The New York Times. 2016 Jun 19.

- Kosoff M. Josh Kushner’s Health-Insurance Start-Up Is Still Bleeding Money. Vanity Fair. 2016 Nov 16.

- Marone V, Dafny L. Oscar Health Insurance: What Lies Ahead for a Unicorn Insurance Entrant? Harvard Business School. 2016.

- Donald J Trump – Healthcare Reform Policy Paper. DonaldJTrump.com. 2016.

- Pear R, Kaplan T. House G.O.P. Leaders Outline Plan to Replace Obama Health Care Act. The New York Times. 2017 Feb 17.

- Keane A. US Health Insurers Give Notice on Obamacare Marketplace. Financial Times. 2017 Feb 6.

- Abelson R. Humana Plans to Pull Out of Obamacare’s Insurance Exchanges. The New York Times. 2017 Feb 14.

- Goldstein A. IRS Won’t Withhold Tax Refunds if Americans Ignore ACA Insurance Requirement. The Washington Post. 2017 Feb 15.

- Kalogeropoulos G. 6 Republican plans to replace Obamacare — an overview. Mediumcom. 2017 Feb 7.

- Porter M. Oak Street Health: A New Model of Primary Care. Harvard Business School. 2017 Feb 24.