Regina E. Herzlinger, McPherson Professor, Harvard Business School, and founder of the Global Educators Network for Health Innovation Education (GENiE)

Group analysis of universities: James Wallace, Senior Research Associate, Harvard Business School

Contact: Regina E. Herzlinger, rherzlinger@hbs.edu

Abstract

What is the message?

The expert participants of the October 2017 Global Educators Network for Health Innovation Education (GENiE) conference generated six predictions about key future healthcare innovations.

Content analysis of the focus and orientation of healthcare innovation courses at the top seven U.S. universities offering courses in medicine and healthcare management found only limited match to the predicted future needs of the healthcare system, particularly needs for nuanced knowledge of how to implement changes.

Interviews with key health care leaders and recruiters highlighted the innovation skills they wanted academia to teach. Academics agreed with these goals and identified the important collaborative efforts that needed to be implemented to achieve them.The article contains examples of academic institutions that have already attained them.

What is the evidence?

Content analysis of published curricula; interviews with 51 innovative healthcare CEOs and top healthcare recruiters; surveys of academics.

Submitted: November 25, 2017; Accepted after review: February 28, 2018

Cite as: Regina E. Herzlinger. 2018. Healthcare Innovation Education in Schools of Medicine and Healthcare Management: Is There Light at the End of the Tunnel? Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 3, Issue 1.

In many sectors of the economy, innovation not only raises productivity—which in turn controls costs, thus both increasing wealth and improving access to goods and services—but it also frequently raises quality. Consider the automobile industry, where costs declined relative to income, thus increasing access, and quality was vastly improved by process innovations, the Japanese model being a prime example.

Innovation in the large-scale healthcare delivery and payor sectors is critical to controlling costs and improving both quality and access. But instead, we are continually presented with mostly bigger versions of the same creaky, outdated machinery as successive consolidations and other attempts to refine existing ways of providing healthcare services raise prices with uncertain effects on quality and access.1,2 As but one example of declining quality offered by current healthcare institutions, a 2016 article estimated that 250,000 U.S. deaths per year were caused by medical error,3 while 18 years ago, the landmark book To Err is Human estimated the maximum number of deaths at 98,000.4 Although the tally of these deaths is somewhat controversial , this important metric of quality in US healthcare has not improved, despite massive cost increases.

The Global Educators Network for Health Innovation Education (GENiE) Group

One reason for the lack of transformational healthcare innovation is the paucity of education specifically designed to prepare executive candidates to innovate. The Global Educators Network for Health Innovation Education (GENiE) Group was created to make innovation a central part of the education of future leaders in healthcare. GENiE represents diverse, global academic institutions, professional organizations, and healthcare consultancies dedicated to teaching innovation to future leaders in healthcare.

When GENiE sponsored its latest conference in October 2017 at Harvard Business School in Boston, the GENiE researchers took advantage of this meeting of the minds to solicit the predictions of professionals seeking to make healthcare more efficient, affordable, and accessible. What innovations did they deem most and least likely in the healthcare space? What effects should those changes have on healthcare innovation education?

The participants at the October 2017 GENiE conference were acknowledged leaders in healthcare innovation from around the world, including current and former executives at Bain & Company, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Johnson & Johnson, Evercore, The World Bank, Massachusetts General Hospital, Cancer Treatment Centers of America, EIT Health (EU), Philips North America, The Cato Institute, Ribera Salud (Spain), TPG Growth (India), and the UnitedHealth Group. In parallel, a strong array of top-flight educational institutions represented health innovation education leaders from across the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Where Is Healthcare Innovation Heading?

The 2017 GENiE conferees made a number of predictions about the most and least likely innovations in the healthcare space:

| 1. On the supply side, generation of potential new products and services by life sciences and technology innovators is highly likely to continue because they are well funded and amply taught |

| 2. On the demand-side, adoption of innovations among payors, providers, and other actors is much more doubtful |

| 3. Healthcare financial systems and payors’ choices tend to reduce adoption of innovation significantly. |

| 4. Patient/consumer-centric innovation is key to improving outcomes |

| 5. Corporate-backed venture capital in the form of “intrapreneurship”: divisions inside large companies that conduct their own R&D will continue to increase. |

| 6. Major regulatory reform, while strongly needed, is unlikely |

To evaluate these predictions, we drew upon diverse sources of information on the current role of innovation in the education of healthcare executives: a broad-based curriculum content analysis, interviews with CEOs and recruiters in the health sector, and surveys of academics who self-identified as being committed to teaching innovation in healthcare.

Where’s The Beef? Curriculum Content Analysis of Healthcare Innovation Courses

We performed content analysis of more than 3,000 online descriptions of courses taught at 32 schools within the top seven U.S. universities offering courses in medicine and healthcare management.5 (Because our purpose is across-the-board analysis with an eye towards educational reform we do not identify universities by name.) We constructed our content analysis of these courses along two axes: focus (narrow vs. broad) and orientation (implementation vs. research).

- Focus: Focus refers to the approach taken to target subjects. Generally, schools appear to focus on medical or healthcare management courses either narrowly (i.e., deep study of ONLY a few specific activities such as biomedical engineering or pharmacology) or more broadly (such as anatomy or digital health), with the chief objective of familiarization.

- Orientation: Courses with an implementation orientation are typically concerned with a particular outcome or objective, e.g., a tangible product, service, or result that is often commercializable. The search terms selected to denote implementation of innovation included entrepreneur, hatch, innovate, invent, patent, and startup. Courses that approach innovation with a “research” orientation, on the other hand, typically focus on experimentation and development of knowledge; the eventual result may be commercialized but that is not the immediate goal. Search terms denoting a research orientation included adopt, commerce, develop, experiment, incubate, research, science, service, and technology.

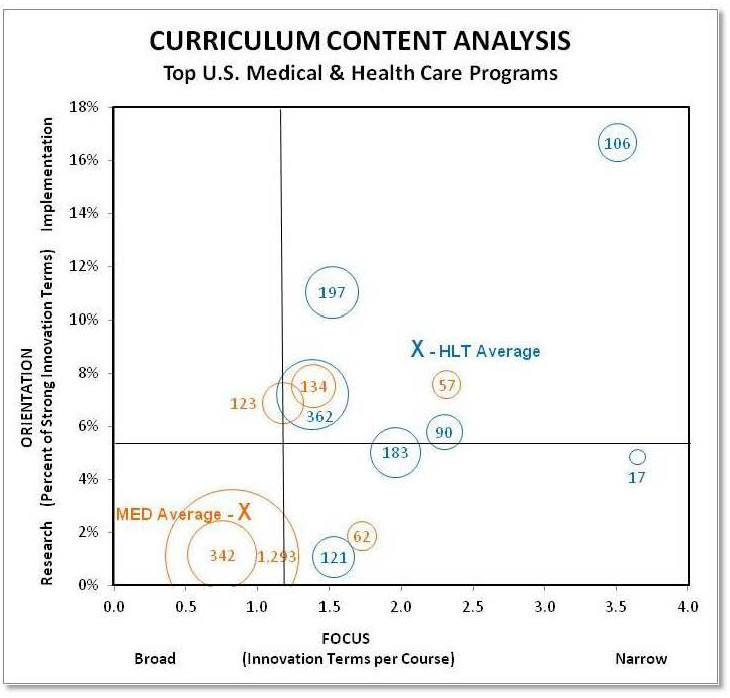

In six of the top seven universities’ course descriptions, only 5% of the course offerings were oriented towards implementation. The remaining 95% of the course descriptions contained words that placed them in the “research” category, i.e., a concentration on the accumulation/ analysis of knowledge (see Figure 1, Curriculum content analysis of top US medical and healthcare programs). Only in the seventh university, a large institution in the Upper Midwest (it is the bubble showing 106 courses in the upper right quadrant of Figure 1), were a more encouraging 16.5% of course offerings in the “implementation” category. The bottom line: even prestigious schools that self-identify as educating healthcare managers are sorely lacking in course offerings that focus on adopting and implementing innovation rather than researching and creating it.

Figure 1. Curriculum content analysis of top US medical and healthcare programs.*

N = 3180 courses across 30 schools at the seven top universities offering courses in medicine and healthcare management.5

- Blue = schools of healthcare management (HLT); Orange = medical schools (MED)

- Bubble size/number = number of courses analyzed at that university

- Quadrants: The vertical bar at 1.2 is the average of the occurrence of any innovation term (implementation/research) per course; the horizontal bar at 5.8 is the average number of terms per course denoting a focus on innovation implementation (rather than research).

* Among the 7 universities analyzed, one had healthcare management courses but no medical school; thus there are 7 blue bubbles but only 6 orange bubbles.

Match Between Six Predictions of Where Healthcare Innovation Is Heading and Current Innovation Curriculum

Below is a comparison of the six predictions of the GENiE participants regarding where healthcare is going with the education offerings gleaned from our content analysis.

- Prediction 1: Generation of potential new products and services by life sciences and technology innovators is highly likely to continue because they are well funded and amply taught

- Response 1: There is clearly extensive teaching about innovation in medical technology, with notable hubs of innovation education; but there is much less education on the implementation of such improvements.

- Prediction 2: The adoption of innovations among payors, providers, and other actors on the demand-side is much more doubtful

- Response 2: There is very little education on innovation for delivery and insurance; of more than 3000 courses, there was not one on payors.

- Prediction 3: Healthcare financial systems and payors’ choices tend to reduce adoption of innovation significantly.

- Response 3: This is another area for which innovation education is sorely lacking.

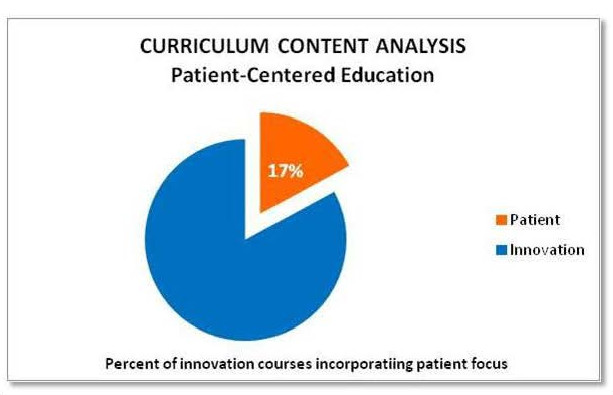

- Prediction 4: Patient/consumer-centric innovation is the key to improving outcomes.

- Response 4: Supportive evidence for this prediction found in the growth of high-deductible plans among well-informed consumers.8 But, again, appropriate education is sparse.

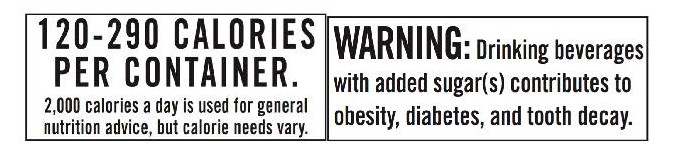

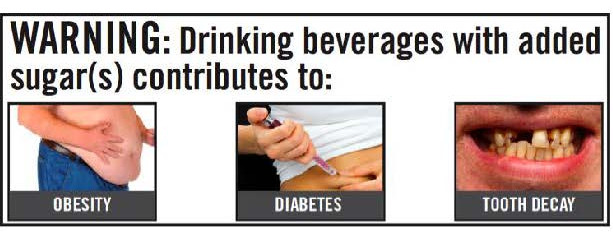

This kind of education can yield important, actionable results, such as the findings by Leslie K. John and colleagues on modifying consumer behavior. 11 Neither of the text warnings shown below produced a significant effect on consumer behavior.

However, the graphic warning label below reduced daily purchase of sugary drinks by 15.5 percent and the average calories per drink purchased from 88 to 75.11

- Prediction 5: Corporate-backed venture capital in the form of “intrapreneurship”: divisions inside large companies that conduct their own R&D will continue to increase.

- Response 5: Issues of organizational design are of great importance, as evidenced in the many failures of innovation in most large, seemingly well-resourced organizations.7 And, in the eyes of an experienced healthcare venture capitalist who attended the 2017 GENiE conference, many accelerators and innovation labs fail: “… because they mute the sharp point of a free market. If an idea is good enough, all the things that accelerators provided will come along anyhow. In the breeding ground for ideas they created, the bad ones took resources away from the good ones.”

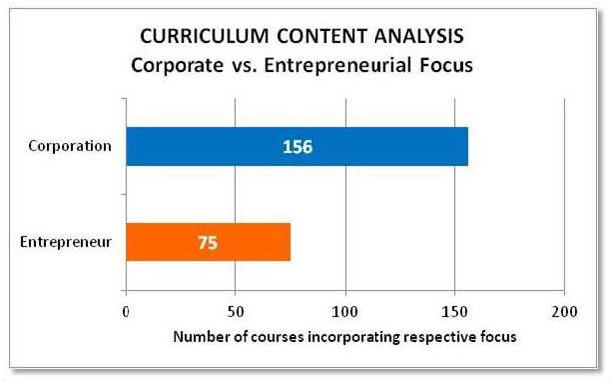

Yet, our content analysis revealed much greater focus on corporate management than on entrepreneurship.

Some of our panelists illustrated novel intrapreneurship divisions designed as largely separate from the parent company to protect them from the “bear hug” that kills off too much innovation. When it’s time to implement a promising innovation, though, the innovation can deploy the parent company’s size and infrastructure to support effective dissemination.

- Bruce Rosengard, Chief Medical, Science, and Technology Officer, Johnson & Johnson: “When I arrived, we started from scratch–which was an advantage. I was able to pull together elements of what is now J&J Innovation and J-Labs, creating a platform for new ventures inside Johnson & Johnson. This has allowed us to invest in early-stage funding, while other sources of seed funding have decreased.”

- Tommy Hawes, Managing Director, and Sandbox Industries: “When we started, we were trying to figure out how to innovate a function in a mature segment of the industry, i.e., venture funding in the Blue Cross Blue Shield system. We did this by ceding control of the investment decision to our investors, a unique concept in venture funding… and it worked because of our culture. We insisted on complete transparency, and over three funds, we moved from 11 to 31 of the 36 Blues plans as investors, and our results have followed this trend.”

- Michael Weintraub, former Managing Director, Optum Ventures: “How did we do it [innovation]? Shortly after (my company was)… acquired by UnitedHealth Group, I was asked a similar question at a conference. I answered, ‘We’re going to innovate at scale. We’re going to use the money, resources, and access to customers of a large company to accelerate our innovation, which is very hard for a small startup to do. And that’s what we did.”

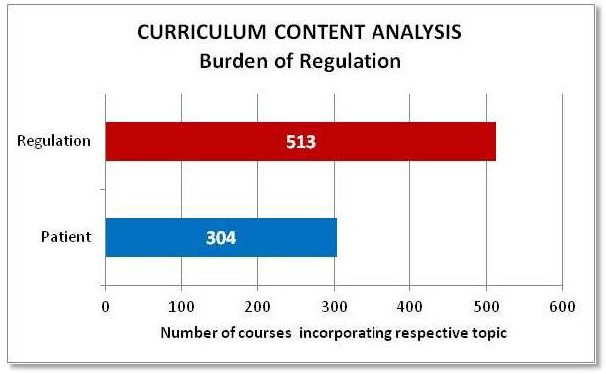

- Prediction 6: Major regulatory reform, while strongly needed, is unlikely.

- Response 6: Our content analysis revealed a greater focus on studying the nature of present regulation than on considering how regulation affects patients.

CEOs and Recruiters: Desired Qualities of Healthcare Innovation Executives

To determine desirable qualities in future healthcare innovation leaders from the perspective of employers, GENiE worked with a market research consultancy to interview 56 CEOs from the world’s largest and most innovative health-sector companies; those transcripts then underwent content analysis. 6

In addition, interviews with 16 leading U.S. healthcare recruiters provided insights in what they look for in senior-level candidates.6 Unsurprisingly, a content analysis of these interviews revealed ‘healthcare’ was the most frequent search term; but some form of the words ‘innovate’ or ‘entrepreneur’ came in second, ahead of ‘company,’ ‘industry,’ and ‘system.’

The recruiters found the hospital sector actively resistant to hiring innovators: “Where you’re getting innovation is everything outside of our hospital institutions.” They noted that, at least among employers who are healthcare providers, they see little “out-of-the-box thinking” and a lack of willingness to reward the type of risk required for substantial innovation. They opined: “institutions are looking for ‘regulated’ and ‘incremental change,’ not radical transformation”. Recruiters also squarely blamed academia for recruiting the wrong kinds of students and teaching them the wrong things in the wrong way. One noted, academia is “still teaching people and tracking people who want to be hospital administrators … you don’t get people who are really gung-ho…to do entrepreneurial things.”

Both recruiters and executives wanted to see students with deep knowledge of the healthcare domain, including a “strong strategic sense of the inter-relationships of manufacturers, distributors, providers, insurers and patients,“ as well as comfort with finance and venture capital and the utilization of data and technology. They were especially eager to find candidates prepared to take the risk of predicting and driving the future, who are self-reflective and -directed; the type of people “not content to have good jobs, but who want to run and build their own companies.” In a word: entrepreneurs.

Academic Leaders’ Views of Healthcare Innovation Education

Surveys of academics reflect an acknowledgment of the urgent need to educate students skilled in innovation—but also keen awareness of a number of roadblocks, including a shortage of business educators knowledgeable about healthcare delivery and insurance, health IT, and medical technology.4 They believe that public health and health administration faculty, on the other hand, often lack knowledge of appropriate managerial skills, entrepreneurial approaches to global health, venture capital, and the case method. These shortcomings are exacerbated by faculty resistance to curricular changes, together with academic incentives to conduct and publish traditional research rather than to foster innovation projects and innovate curricula. Additionally, scholars may have difficulty accessing data on real-world organizations or course material that integrates healthcare and business school curricula.

Conclusions

Those of us who educate healthcare executives have before us a daunting task—and an exhilarating opportunity. Global healthcare faces a threefold crisis of unsustainable economics, erratic quality, and unequal access. The GENiE researchers find that CEOs are keenly aware of this crisis and of the vital role of innovation in finding our way out of it. The same is true of many academics, but they face considerable obstacles in reshaping curricula to support the necessary focus on education towards innovation.

We can support world leaders who are equal to the challenge of innovating 21st-century healthcare if we create unprecedented collaboration among disciplines and between academia and business; revamp curricula that may no longer serve us; and use the academic tools we know to be effective. We have already been notable examples of progress. In the US and Canada several noteworthy academic programs in healthcare innovation have been created.

- Harvard Business School launched its Healthcare Initiative (HCI) in 2005, offering courses, industry speakers, career coaching, treks, and alumni engagement for aspiring healthcare innovation leaders.

- The University of Alabama Collat School of Business offers MBA students (and non-MBA graduate students in science) a Graduate Certificate in Technology Commercialization and Entrepreneurship. The program blends classroom and experiential learning to move scientific discovery and inventions out of the lab and into the marketplace.

- The University of Texas at Austin’s Dell Medical School, whose stated mission reads, “We will revolutionize how people get and stay healthy.” That is further broken down into: “Improving health in our community as a model for the nation; Evolving new models of person-centered, multidisciplinary care that reward value; Advancing innovation from discovery to outcomes; Educating leaders who transform healthcare; and Redesigning the academic health environment to better serve society.”

- Duke University’s Masters of Management in Clinical Informatics program engages students with concepts and practice at the frontier of digital health.

- The University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management has launched a Global Executive MBA program in Healthcare and the Life Sciences, focused on engaging experienced leaders from the full health sector value chain and helping them learn how to engage at the interfaces of traditional silos.

Across the Atlantic, the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) has formed EIT Health, a consortium that promotes research, education, and business expertise to “accelerate entrepreneurship and innovation in healthy living and active ageing with the aim to improve quality of life and healthcare across Europe.”7 The Copenhagen Business School has both a Department of Innovation and Organizational Economics and is affiliated with the Innovation Growth Lab, which describes itself as “A global laboratory for innovation and growth policy, bringing together governments, researchers and foundations to trial new approaches to increase innovation, accelerate high-growth entrepreneurship and support business growth.”10

All the stakeholders – providers, payors, life sciences, investors, and government – must support educational innovators like these in disseminating their efforts to create the executives healthcare needs.

We are hopeful. If any scholars should believe in their ability to spearhead substantial change, it is those in healthcare. After all, their area of expertise has more than once vanquished the seemingly impossible, whether by substantially increasing life spans or revoking the death sentence of AIDS in the developed world. Will our crowning achievement be to broaden access to healthcare across the world through cost-effective managerial innovations?

References

- Herzlinger RE, Richman BD, Schulman KA. Market-based solutions to antitrust threats–the rejection of the Partners settlement. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(14):1287-1289.

- Gaynor M, Mostashari F, Ginsburg PB. Making Healthcare Markets Work: Competition Policy for Healthcare. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2017;317(13):1313-1314.

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. British Medical Journal. 2016;353:i2139.

- Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000. https://doi.org/10.17226/9728.

- Best U.S. Healthcare Management Programs. U.S. News & World Report. https://www.usnews.com/best-graduate-schools/top-health-schools/healthcare-management-rankings?int=abc409. Accessed October 19, 2017

- Herzlinger RE. Benchmarks for Confronting the Challenges for Innovation in Healthcare with a Modern Curriculum. GENiE 2012 Annual Conference; Boston, MA. Harvard Business School, 2012. http://www.thegeniegroup.org/publications/. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- Herzlinger R, Wiske C. Disseminating and Diffusing Internal Innovations: Lessons from Large Innovative Healthcare Organizations. Health Management Policy and Innovation. 2017;2(2). https://hmpi.org/2017/09/08/disseminating-and-diffusing-internal-innovations-lessons-from-large-innovative-healthcare-organizations/. Published July 1, 2017. Accessed October 19, 2017.

- Thaler, RH. Why So Many People Choose the Wrong Health Plans. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/04/business/why-choose-wrong-health-plan.html. Published November 4, 2017. Accessed January 1, 2018.

- EIT Health. https://www.eithealth.eu/. Accessed December 30, 2017.

- Copenhagen Business School. Innovation Growth Lab. http://www.innovationgrowthlab.org/affiliations/copenhagen-business-school. Accessed December 30, 2017.

- Donnelly GE, Zatz LY, Svirsky D, John LK. Graphic Warning Labels Curb Sugary Drink Purchasing. GENiE 2017 Annual Conference; Boston, MA. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/534853fbe4b021e125a8a4ee/t/5a859a8041920237fe9124b0/1518705282259/GENiE+2017+White+Paper+2018+02.13.pdf. Published February 14, 2018. Accessed February 23, 2018.