Raman Sohal, Onil Bhattacharyya, Will Mitchell, University of Toronto

Contact: Will Mitchell, william.mitchell@Rotman.Utoronto.Ca

Abstract

What is the message?

Social enterprises have been able to leverage resources from a range of partners along the health systems value chain in order to fulfil their core mission of health services delivery at the base of the pyramid. The ability to draw upon existing infrastructure and distribution channels has enabled these social enterprises to significantly reduce their start-up and ongoing costs and simultaneously expand their reach. As the examples illustrate, value chain integration requires health services organizations to be deliberate in reaching disparate types of partners that are needed along stages of their value chains from financing, setting up a clinic, and health service delivery. In doing so, the lead organizations benefit from enabling strategies in the form of developing an efficiency core and gaining strength in four key types of management skills.

What is the evidence?

A mixture of primary interviews plus reviews of studies in the published literature.

Submitted: October 17, 2017. Accepted after review: December 20, 2017

Cite as: Raman Sohal, Onil Bhattacharyya, Will Mitchell. Value Chain Integration Strategies in Global Health. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 3, Issue 1.

Introduction

Health systems around the world are increasingly recognizing the benefits of value chain integration (VCI) strategies to foster scalable services (Kim, Farmer, & Porter, 2013; Porter & Teisberg, 2006). VCI strategies involve coordinating the activities of partners that help design, develop, produce, and deliver goods and services to customers (Adner, 2006; Mitchell, 2014). These strategies help global health services that target base of the pyramid clients overcome barriers to growth that arise from the complexity of the broader ecosystem in which healthcare activities are embedded. VCI offers the potential for health service organizations to work with skilled partners for funding, health services delivery, logistics, political support, and other key elements of the healthcare value chain. Yet we are only beginning to understand the nature of VCI in global health, as well as the challenges that organizations face in implementing the strategies.

This qualitative study examines how health services delivery organizations use value chain integration to achieve scale lower and middle income countries. We describe how ten private sector global health organizations operating in Africa, the Americas, and Asia are using VCI strategies, highlighting both successful routes and challenges to achieving sustainable scale. We selected the cases based on their ability to help us refine and develop categories of VCI as an emerging conceptual framework in global health delivery. We identify three main mechanisms for using a VCI strategy to scale up health services delivery: identifying mutual dependency with partners, creating an efficiency core (Wong et al., 2014), and building a strong set of four types of management skills, including financial skill, quality management, supply chain management, and client relationships. The base conclusion is that – despite real challenges – creating value chain integration partnerships with diverse actors can help global health enterprises serve clients effectively.

Table 1 summarizes the ten cases. Four organizations operate in one country while the remaining six operate in two to 42 countries. Six have for-profit legal structures and four are non-profit.We drew on existing literature and then supplemented the data by interviewing leaders of five of the organizations. The published research and interviews provide lessons about how organizations implement VCI strategies.

| Table 1. Examples of Value Chain Integration Strategy | |||

| Organization | Mutual Dependency | Management Capabilties | Efficiency Core |

| 1. Healthy Entrepreneurs

(Congo, Uganda, Tanzania, Ghana, and Haiti)

Source: Literature |

Health Entrepreneurs (HE) has developed a full supply and distribution chain solution to bring high-quality and affordable health products to rural regions. HE streamlines the supply chain, reducing inefficiencies caused by “middlemen” and sub-contractors. Their team equips, trains, and provides technical support to a network of franchisees that in turn provide health education and sell essential medicines and products to remote communities. | Healthy Entrepreneurs offers of a combination of health education, screening, counseling, referral and access to products. HE has developed a full supply and distribution chain solution to bring high-quality and affordable health products to rural regions. |

|

| 2. Jacaranda Health

(Kenya)

Source: Literature and interviews |

By offering high-quality maternity services, Jacaranda has been able to develop strong relationships with government clinics in Kenya. Jacaranda provides capacity building training to government hospitals to help them improve their maternity services. | Jacaranda Health in Kenya, operates a chain of maternity hospitals and provides comprehensive maternity care at a fifth of the cost of other private hospitals. Jacaranda uses a fee-for-service model and combines quality and affordability in its service offering. The maternity hospitals are located in in peri-urban Nairobi, in the backyards of the women who need them most. The organization provides respectful patient-centerd obstetric care, safe delivery, family planning, and postnatal care. |

|

| 3. Lifenet International

(Burundi, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo) Source: Literature and interviews |

Lifenet originally piloted a nurse-led model in which nurses would do outreach in the communities to deliver primary care. During the pilot phase, however, Lifenet realized that existing church-run medical centers not only already provided healthcare to Burundi’s rural poor, but these centers had significant buy-in from the community. Rather than set-up a parallel system, Lifenet abandoned the nurse-led community model and developed a franchise conversion model to bring existing providers into the Lifenet network, which now includes 90 health centers in three countries in Africa in Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. | Lifenet provides comprehensive solutions to management, medical and supply problems. LifeNet International’s conversion franchise model includes nurse training, management training, growth financing, and pharmaceutical supply to transform quality of care and increase range of services in primary healthcare facilities in Burundi, Uganda, and the DRC. Lifenet provides logistics, financing, equipment and training services to existing, faith-ba sed health centers in East Africa. Lifenet’s partners finance their own operations, as well as medicine and equipment purchases, ensuring local responsibility and sustainability. |

|

| 4. North Star Alliance

(12 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa)

Source: Literature and interviews |

North Star has forged alliances with different types of actors in order to obtain the resources, both tangible and intangible, its needs in order to deliver healthcare to mobile populations along the transport corridor in Africa. North Star Alliance received significant public support from the humanitarian, government and the private sector. The impact of the HIV/AIDS crisis on a productive workforce (i.e., truck drivers) enabled North Star to leverage support from potential allies such as the United Nations World Food Programme and from partners in the commercial sector, such as the global courier company TNT Express. These partnerships enabled North Star to obtain resources and capabilities needed to launch the Roadside Wellness Centre network in ten countries in Africa. | North Star Alliance is a non-profit that has established a network of roadside health clinics at major truck stops and border crossings to serve hard-to-reach populations across Africa, including truck drivers, sex workers and general community members. North Star operates in collaboration with government, businesses and civil society partners and identifies disease hotspots along major transport routes, where clinics are housed in blue-box shipping containers. North Star forms teams of local community health workers to conduct outreach activities to reach its target population, which comprises mobile populations. North Star uses principles of logistics and supply chain management to establish network of Roadside Wellness Centres in 10 countries in Africa. The organization has developed an electronic health passport that syncs across 10 countries. |

|

| 5. Operation Asha

(Cambodia, India)

Source: Literature |

Operation ASHA partners in locations with extensive foot traffic. For patient convenience, Operation ASHA establishes TB treatment centers within strategically placed shops, homes, temples, and health clinics. The organization also works closely with other NGOs and governments at international and national levels. | Patient convenience, community mobilization, and comprehensive counselling form core components of the organization’s offering. Operation ASHA trains community members (often former patients) to become TB health workers who are responsible for identifying new patients, ensuring adherence to the drug regimen, and carrying out regular educational campaigns. |

|

| 6. Penda Health

(Kenya)

Source: Literature and interviews |

Penda Health partners with a range of partners including factories, universities and insurance companies in order to scale its operations in Kenya. By building alliances with organizations that can offer a paying client base, Penda not only scales up its operations, it also strengthens its sustainability. | Penda Health operates a chain of primary care clinics in Kenya. Penda offers affordable, high-quality, standardized, evidence-based medical care for the whole family, including scarce women’s sexual and reproductive services such as breast and cervical cancer screening, provided by friendly, caring staff via an outpatient clinic model. In addition to curative healthcare services, Penda offers “Wellness Checks” for men, women, and children and some counseling, which all fall under the umbrella of preventive healthcare services. |

|

| 7. Riders For Health

(Seven Countries In Sub-Saharan Africa)

Source: Literature |

The Riders for Health network of technicians regularly travels to service vehicles in the communities that health workers serve. Riders works with ministries of health, international and African NGOs, private-sector organizations, local community-based organizations, and religious groups, to improve access to healthcare for over 21 million people. | Riders for Health manages motorcycles, ambulances, and other four-wheel vehicles used in the delivery of healthcare in seven countries across Africa. Rider’s network of technicians regularly travels to service vehicles in the communities that health workers serve. Riders works with ministries of health, international and African NGOs, private-sector organizations, local community-based organizations, and religious groups to improve access to healthcare for over 21 million people. In addition, Riders’ programs provide training and employment opportunities to build local capacity. |

|

| 8. Unjani Clinics

(South Africa)

Source: Literature and interviews |

Unjani Clinics is backed by a logistics supplier, Imperial Health Sciences Ltd., through its CSR activities. Unjani has been able to obtain the start-up capital needed to establish a social franchise of primary care clinics through Imperial. Imperial provides the working capital for Unjani Clinics to be set up. Unjani Clinics also enable Imperial to pursue opportunities to grow new markets for clients in Africa. Imperial was cognizant that by catering for a segment of the population which was currently under served, Unjani Clinics offered a means to grow its core pharmaceutical and consumer clients’ sales volumes. | Unjani Clinics uses a social franchise model to achieve scale in South Africa. The clinics provide primary healthcare services at an affordable price to under-served communities in South Africa. The fee-based service model enables sustainability and the empowerment of black women through the use of a franchised business model. Unjani’s clinics are made in South Africa from converted second hand shipping containers. Critical to the success of each location is the selection of the nurse and the clinic location. Nurses are selected from the communities they serve. Unjani provides back-end support such as logistics, supply chain, pricing and supplier services, as well as training and mentoring to ensure that each nurse has the necessary tools to own and operate a sustainable business. | · Task-shifting

· Community nurses · Social franchise |

| 9. VisionSpring

(42 countries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas)

Source: Literature |

VisionSpring has leveraged its partnership with existing organizations, such as BRAC, to expand its reach in other countries. While in South America VisionSpring has adopted a hub-and-spoke model using its own stores as its main distribution channels and a variety of local partners, in Bangladesh VisionSpring leverages the national distribution capacity of a single partner – the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC). This partnership enables VisionSpring to take advantage of BRACs’ vast network as a distribution platform. | VisionSpring uses a “business in a bag” model to generate revenue that enables it to provide eye screening for the poor. The organization also uses shared distribution channels to expand its reach in 43 countries. VisionSpring uses a Vision Entrepreneur (VE) distribution model: this involves training and empowering local people, mostly women, to conduct basic eye exams in low-resource settings and to sell low-cost, durable reading glasses. One pair, with a case and cleaning cloth, costs from US$2.50 to $4.00. VisionSpring employs a retail component to its business in India through both stand-alone optical shops and shops located within partner hospitals and surgical centers. These optical shops serve base-of-the-pyramid customers by providing comprehensive eye exams and selling affordable prescription, reading and sunglasses. | · Hub-and-spoke model

· Vision Entrepreneurs · “Business-in-a-bag” model |

| 10. Ziquitza Healthcare Limited

(India)

Source: Literature |

Ziquitza Healthcare Limited offers “white labelling” opportunities, which enables private hospitals to brand Ziquitza ambulances. While the hospitals receive publicity and visibility through branded Ziquitza vehicles, Ziquitza in return is able to mobilize the financial resources it needs to subsidize its core operations, which focus on emergency transport for the poor. In sum, Ziquitza has established a range of revenue streams that allow it to remain socially inclusive and financially sustainable.

|

Ziquitza is built on two models for emergency transportation: Dial 1298, a fully private service, and Dial 108, a public service supported by state governments. For its 1298 model, Ziquitza operates a private ambulance service in Mumbai, Kerala, Bihar, and Punjab that charges wealthier patients more to be transported to private hospitals, using that revenue to cross subsidize its discounted or free service to lower-income patients. Through the 1298 program, Ziquitza operates a network of fully equipped Advanced and Basic Life Support Ambulances across two states in India. 1298’s business model uses a sliding price scale driven by a patient’s ability to pay, which is determined by the kind of hospital to which patients choose to be taken. | · Cross-subsidization

· Tiered-pricing strategy · Narrow offering Revenue generation |

Table 2 lists nine common value chain steps for health services delivery: 1) financing, 2) infrastructure and set-up, 3) obtaining real-estate, 4) registration and permits, 5) recruitment, 6) supply chain management, 7) identifying clients, 8) marketing and branding, and 9) delivery.

| Table 2. Nine Value Chain Integration Steps For Health Services Organizations | |

| 1. Financing | Obtaining financial capital necessary to deliver the product or service. |

| 2. Infrastructure and set-up | Obtaining physical infrastructure (e.g., clinic) needed to deliver the health product or service |

| 3. Real estate | Obtaining the land from which the organization can operate in order to deliver a product or service |

| 4. Registration and permits | Obtaining necessary registration and permits (e.g., ministry of health permits) to provide a health service |

| 5. Recruitment | Hiring administrative and clinical personnel |

| 6. Supply chain management | Management sourcing of necessary supplies (e.g., medical supplies) |

| 7. Identifying clients | Identifying relevant customers |

| 8. Marketing and branding | Promoting the product or service |

| 9. Delivery | Providing the product or service to the target customers |

Mechanisms for a VCI Strategy

Identifying mutual dependency with partners

An underlying tenet of VCI strategy is that organizations should not try to do everything themselves, especially activities where other actors in the ecosystem have superior skills and positions (Porter, 1985; Mitchell, 2014). Capron and Mitchell (2013) highlight that strategic challenges lie not only in identifying which resources are needed, but how to obtain resources. The organizations in our sample developed alliances with partners at different stages of their value chains (Table 1). Resource-limited health services organizations that are effective at identifying relevant mutual dependencies can often borrow critical resources from partners in order to pursue expansion goals. Kramer and Pfitzer (2016), for example, note: “The first large-scale program to diagnose and treat HIV/AIDS in South Africa was introduced by the global mining company Anglo American to protect its workforce and reduce absenteeism.” In 2016, Anglo American formed an alliance with UNAIDS to support ProTest HIV, a global initiative that encourages people to be tested for HIV. Research demonstrates that scaling global health delivery requires support from a range of partners, including governments, bilateral and multilateral aid agencies, and the private sector (Bhattacharyya et al., 2010). Examples from our study offer powerful insights.

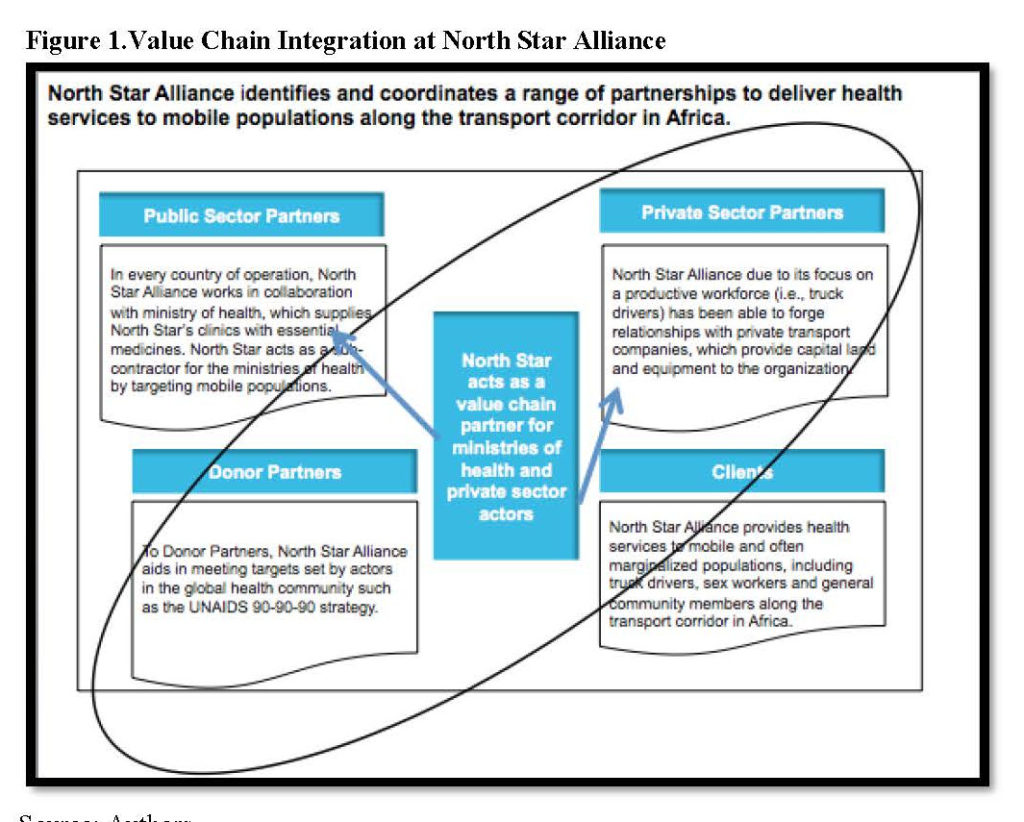

North Star Alliance

North Star Alliance in Sub-Saharan Africa has used value chain partners predominantly in steps one, three, four, six, and seven of the value chain. North Star’s value chain requires that the organization acquire land, set up clinic infrastructure, maintain medical stock supply in order to provide healthcare delivery to truck drivers and sex workers. As a non-profit health services organization, North Star has developed alliances with different types of actors in order to obtain tangible and intangible resources it needs to deliver healthcare to mobile populations along transport corridors in several African countries. When it launched its operations, North Star received significant public support from the humanitarian, government, and private sectors. The impact of the HIV/AIDS crisis on a productive workforce of truck drivers enabled North Star to leverage support from potential allies such as the United Nations World Food Programme (UNWFP) and partners in the commercial sector such as the global courier company TNT Express. These partnerships allowed North Star to obtain the financial resources needed in the first stage of the value chain to establish a network of 36 Roadside Wellness Centres in ten countries.

Health services organizations that can align goals throughout their partnerships often can expand their resource base. In Kenya, as Figure 1 depicts, North Star Alliance has been able to formulate an alliance, along step three of its value chain, to procure free land for all eight of its clinics from the Kenya National Highway Authority (KENHA). While many entrepreneurs bid for the same land, North Star reached an agreement to set up its clinics along the transport corridor and write-off rent – a significant cost. KENHA, due to its contracts with investment banks, must provide HIV/AIDS services to its contract employees, who are highway construction workers. A manager from KENHA told us that “Because of our agreements with the investment banks, there is a clause that we have to provide HIV services to our workers. We don’t have the capability to do this on our own. We had a hard time finding an NGO that provides HIV services to immigrant workers on contract along the highway. North Star is the only organization we know of. North Star is helping us.”

Unjani Clinics

Unjani Clinics is a social franchise that has established nurse owned and operated clinics for the underserved in South Africa. Unjani is the corporate social responsibility arm of a pharmaceutical company, Imperial Health Sciences. The Unjani Clinic model contributes to strengthening South Africa’s health system and creating employment under the national Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) program. The BEE Codes of Good Practice compel large companies to spend three percent of their net profit to develop small and medium enterprises with a majority black shareholding – two percent for businesses within their corporate supply chain and one percent to help grow other businesses (Gordon Institute of Business Science, 2016). Mutual dependency between Unjani and this South African government initiative in turn helped Imperial Health Sciences position itself to attract government tenders (step one in the value chain) for its core business operations.

Leveraging shared distribution channels

Leveraging shared distribution channels offers a powerful means of benefiting from mutual dependency. Within the value chain, an important stage is setting up infrastructure to establish clinics (step two). Procuring real estate to set up operations can be costly for social enterprises targeting the base of the pyramid. One means through which organizations in our sample have managed to reduce or write-off set-up costs is by leveraging shared distribution channels.

Lifenet International

Lifenet’s conversion franchise model largely dispenses with staffing and focuses on managing existing providers in the healthcare delivery value chain in Burundi, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lifenet originally piloted a model in which nurses would do outreach in the communities to deliver primary care. During the pilot phase, Lifenet realized that existing church-run medical centers not only already provided healthcare to Burundi’s rural poor, but also had significant buy-in and trust from the community. Rather than create a parallel system, Lifenet abandoned the nurse-led model and developed a franchise system to bring existing providers into the Lifenet network. This enabled the providers to increase the value of their primary care delivery to the rural poor. Lifenet’s franchise model includes nurse training, management training, growth financing, and pharmaceutical supply.

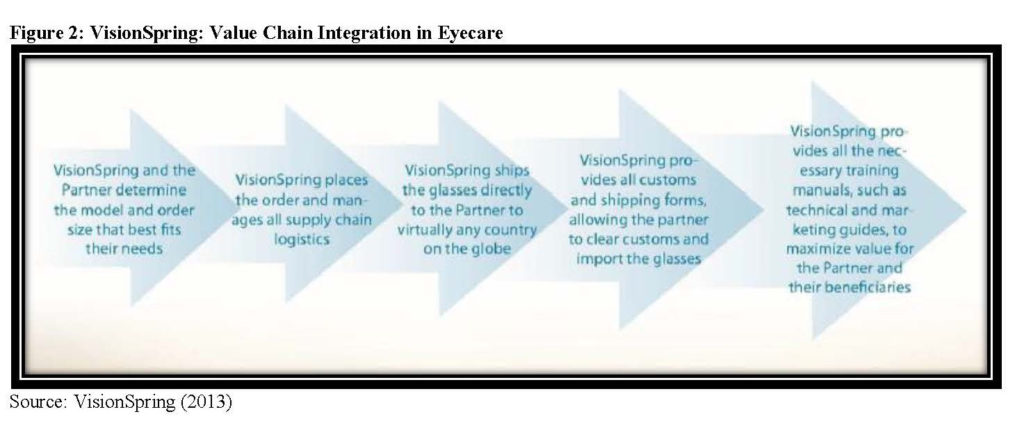

VisionSpring

VisionSpring partners even more intensively than Lifenet to supply eyeglasses to partners via an existing distribution system’s existing client base in countries throughout the world. In Bangladesh, VisionSpring has leveraged the national distribution capacity of the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC). VisionSpring uses BRAC’s existing sales force, which includes approximately 80,000 women who sell baskets of health-related goods such as Band-Aids and Aspirin (Hassey & Kassalow, 2014). By partnering with BRAC, VisionSpring achieved rapid scale and reduced its own training and administrative costs. In South Africa, VisionSpring partnered with Unjani Clinics (Center for Health Market Innovations, 2013). While Unjani’s patients are able to access primary care services at the clinics, vision screening was problematic as the Unjani network did not want to offer the screening without offering clients the ability to purchase the glasses at the point of care. VisionSpring places orders for eyeglasses for its partners and manages all supply chain logistics (VisionSpring, 2013). VisionSpring has found a sustainable specialized position in healthcare delivery and is coordinating a focused piece of the healthcare delivery value chain through extensive partnerships.

These examples illustrate how social enterprises have been able to leverage resources from a range of partners in order to fulfil their core mission of health services delivery at the base of the pyramid. The ability to draw upon existing infrastructure and distribution channels has enabled these social enterprises to significantly reduce their start-up and ongoing costs and simultaneously expand their reach. As the examples illustrate, value chain integration requires health services organizations to be deliberate in reaching disparate types of partners that are needed along stages of their value chains from financing, setting up a clinic, and health service delivery.

Simply creating and managing partnerships is not enough for a successful VCI strategy. In addition, the lead organizations benefit from enabling strategies in the form of developing an efficiency core (Wong, Zlotkin, Ho, & Perumal, 2014) and gaining strength in four key types of management skills.

Enabling Strategy 1: Developing an Efficiency Core

The global health literature highlights standardization and simplicity as necessary ingredients for scaling interventions (Cooley & Kohl, 2006; Simmons, Fajans, & Ghiron, 2009). The notion of the efficiency core refers to the standardized part of a model that can be replicated with minimal modification to fit local contexts (Wong et al., 2014). Each of our cases has an identifiable efficiency core, as Table 1 summarizes.

- North Star Alliance: North Star has an efficiency core consisting of a blue-box shipping container that provides the office, together with a lean staffing model comprised of five individuals: clinical officer, HIV testing counselor, site coordinator, receptionist, and security guard.

- Unjani Clinics: Unjani has an efficiency core consisting of a shipping container clinic owned and operated by a nurse from in the local community. Unjani trains nurses in entrepreneurship and business management.

- VisionSpring: VisionSpring has an efficiency core consisting of Vision Entrepreneurs who use a “Business-in-a-Bag” approach to operate micro franchises, traveling from village to village to conduct vision camps, check eyesight, and sell glasses through door-to-door sales (Hassey & Kassalow, 2014).

- Riders For Health: Riders’ efficiency core is a fleet management system. The system involves managing health workers’ motorcycles, conducting regular preventive maintenance, and training workers (Business, 2014). Riders developed a replication team that can introduce their system in any country or any project of any size. For example, the team replicated the Riders system in less than two months in Liberia during the Ebola crisis.

- Jacaranda Health: Jacaranda uses a standardized model targeted on maternity care for its chain of clinics in Kenya.

In addition to creating an efficiency core as part of pursuing a VCI strategy, organizations need strong management capabilities in order to create value for hard-to-reach and last mile populations at the base of the pyramid.

Enabling Strategy 2: Four Types of Management Capabilities

Four types of management capabilities support the VCI strategies in our organizations. The first three categories are supply-side factors: developing financing strategies, driving quality, and investing in strong supply chain management. The fourth category emphasizes the demand-side factor of building strong client relationships. Table 3 offers examples.

| Table 3. Four Types of Necessary Management Capabilities | |

| Management capabilities | Examples |

| 1. Supply-side: Developing financing strategies | Ubuntu Afya Kiosks: Ubuntu Afya operates medical centers in Kenya that are co-owned by communities organized into cooperative societies. The community groups develop business enterprises that yield income to cross-subsidizes the costs of providing Maternal and Neonatal Health (MNH) services. Examples of income-generating activities include soft drink depots, safe water sales, motorbike taxi services, and mobile money pay stations. The medical centers are run by clinical officers and Community Health Volunteers that have a stake in the enterprise. |

| 2. Supply-side: Driving quality | Penda Health: Penda has developed a system whereby a mystery patient is sent to each Penda clinic every week to identify risks that may undermine the delivery of quality care. A clinic receives one demerit score per identified risk and the goal is to achieve a score under ten per month. While Penda’s clinics are run by nurses the organization has developed a Medical Advisory Board whereby physicians conduct chart review of nurses’ charts. Physicians audit ten per cent of the charts per week; where there are gaps in care, physicians provide support to the nurses to ensure clinical quality. |

| 3. Supply-side: Investing in strong supply chain management | Lifenet: Operating in Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Uganda, management training comprises a key component of Lifenet’s efficiency core. By linking rural partner health centers with local and regional wholesalers, which deliver medicines directly to health centers, Lifenet has removed bottlenecks in the medical supply chain. Prior to launching the program, Lifenet discovered health center nurses were often purchasing medicines themselves: spending days traveling to the capital cities by public transportation in order to buy whatever was in stock at whatever price and quality available, before making the long return journey to their health centers. |

| 4. Demand-side: Building strong client relationships | Operation ASHA: Patient convenience, community mobilization, and comprehensive counselling form core components of Operation ASHA’s offering. By establishing centers where there is significant foot traffic of base-of-the-pyramid consumers, Operation ASHA is able to address many of the critical demand side factors that prohibit lower-income consumers from seeking and adhering to TB treatment, such as transportation and time lost due to travelling to and from clinics. |

Supply side: Develop financing strategies

A crucial stage of any value chain is the financing stage, which involves the ability of an organization to fund core operations in a scalable manner (Chandy, Hosono, Kharas, & Linn, 2013). Several of the organizations use fee-for-service models, commonly with consultation fees plus additional fees for medicines and lab services. However, fee-for-service models can face strong challenges. Jacaranda Health, which launched its operations in 2011, runs a fee-for-service model in two maternity clinics in Kenya. The CEO of Jacaranda notes: “Hospitals are high-fixed cost ventures. We still haven’t broken even. We’re almost there and we hope to do so by this December.” Beyond fee-for-service, several organizations use complementary financing models that support free or subsidized services. The following examples focus on the first step of the value chain, where developing a sustainable financing strategy is in integral component of an organization’s value chain.

Penda Health: Fee for service

Penda Health has adopted a fee-for-service model for its chain of primary care clinics in Kenya. Penda’s co-founder notes: “When we first started operations in 2012 it took us years and years to break even. Now if we set up a clinic we can break even in six to eight months.” Penda’s financing strategy involves finding a client base amongst populations that have the ability to pay, such as factory workers and university students.

Penda partners with schools and factories to drive high volumes to their clinics. For example, Penda partnered with the Management University of Africa (MUA) to support a university-sponsored capitated health insurance scheme for students and staff at MUA. The on-campus clinic at MUA caters to 800 students and staff who have employer-sponsored insurance. Penda also partnered with the Masaai Flowers Factory to provide health services to factory workers, using a post-paid model. Under this model, the factory workers do not pay out-of-pocket at the point of service. Instead, Penda invoices Masaai Flowers at the end of each month and the company deducts the healthcare costs from the employees’ pay cheques. Penda is currently expanding its post-paid model to attract other large employers.

Unjani Clinics: Social franchises

In South Africa, Unjani’s fee-based service model enables sustainability and the empowerment of black women through franchised businesses. The ownership model has a built in incentive whereby the professional nurse increases her ownership share annually, based on a franchise agreement with Imperial Health Sciences Limited. The nurse initially pays about US$790 as a commitment fee, which covers the cost of management training in areas such as marketing, standard operating procedures, bookkeeping, record keeping, IT skills, and Unjani systems. When Unjani began in 2010 the nurses were paid a full salary, as Imperial was not convinced the nurses had an appetite for financial risk (Gordon Institute for Health Sciences, 2016). Once the pilot phase was over, however, the model was structured such that as a clinic breaks even, the extra profit becomes the nurse’s salary. Imperial also provides working capital. Each Unjani clinic receives working capital of $900 a month for the first 8 months, then $600 per month for the next 8 months, and finally $300 for the next eight months. The contribution helps the clinic to set up and to build up a client base.

Ziquitza Healthcare Limited: Complementary revenue

Ziquitza Healthcare operates an ambulance service in India. Ziquitza’s business model uses a sliding price scale driven by a patient’s ability to pay, which is determined by the kind of hospital to which patients choose to be taken (public or private). Ziquitiza generates complementary revenue from private hospitals that advertise their services on Ziquitza ambulances (Center for Health Market Innovations, 2016).

Supply side: Drive quality

Driving quality refers to all nine steps of the value chain. As social enterprises expand in size, managers face challenges to maintain quality along each stage. Growth requires robust monitoring to ensure that quality control mechanisms are adhered to by each franchise or clinic.

Penda Health’s eight clinics in Kenya have systematically found ways to compete on quality. Penda has developed a system whereby a mystery patient visits each Penda clinic every week to identify risks that may undermine the delivery of quality care. A clinic receives one demerit score per identified risk – the goal is to achieve under ten demerits per month. Penda’s co-founder told us that “clinics that perform above average are given a bonus.”

In addition, Penda has created a Medical Advisory Board. Physicians who are members of the Medical Advisory Board review nurses’ charts, auditing ten percent of the charts per week. Where there are gaps in care, physicians provide the nurses with advice about clinical quality. Penda’s co-founder reports that where there is clustering of errors in a particular category, the nurses receive refresher training. Penda further surveys its clients to understand whether clients are satisfied with the care they receive at the clinic.

Supply side: Invest in strong supply chain management

Supply chain management, step six, is a key component of value chain integration. The supply chain is focused on conveying products and services from a beginning point to an end point. Supply chain management involves bulk storage and transportation (Feller, Shunk, & Callarman, 2006).

Healthy Entrepreneurs

Health Entrepreneurs deploys a last-mile distribution model to deliver affordable and reliable health products and services to the poorest families in rural areas. Healthy Entrepreneurs has created its own end-to-end distribution chains. Through a network of trained micro-entrepreneurs who operate pharmacies and health facilities, the organization manages an end-to-end value chain of reliable products and practical health information. In order to prevent stock outs, Healthy Entrepreneurs delivers products directly to the entrepreneurs via local depots (Center for Health Market Innovations, 2016).

Lifenet International

By linking rural partner health centers with local and regional wholesalers that deliver medicines directly to the centers, Lifenet has removed bottlenecks in the medical supply chain. Prior to launching the program, nurses were often purchasing medicines themselves: spending days traveling to cities by public transportation in order to buy whatever was in stock at whatever price and quality available, before making the long return journey to their health centers. By developing supplier relationships with local and regional wholesalers, Lifenet’s health centers avoid stock-outs, manage debt, and are financially viable, ensuring their sustainability.

Demand side: Build strong client relationships

While healthcare organizations face temptations to focus on supply side factors, the last stage of a social enterprises’ value chain is often the delivery of a healthcare service. Research reveals that simply providing a needed health service often is not enough (Wong et al., 2014). Koh, Hedge, & Karamchandani (2014) note that some markets offer “pull” products, which most target customers readily demand, such as microfinance loans to credit-starved households at much lower interest rates than money lenders.

In contrast, health is commonly a “push” product. Consumers “do not readily perceive the need for these [push] products as they are unaware of the problem, solution, or both. Often, even if they are aware of the problem, they are unable to easily try out the new solution to understand its value proposition, leading them to make do with established, inferior solutions” (Koh et al., 2014: 23). For social enterprises providing health services to lower-income populations, addressing the last stage of the value chain, which centers on the demand side, is key to driving scale and viability.

North Star

While North Star establishes its container clinics along the transport corridor, interviews with managers, clinic staff, and clients revealed that despite the proximity of the clinics to the truck-stop parking lots, it was often difficult for drivers to leave their trucks in order to seek care. A truck driver parked at the border of Kenya and Tanzania told us: “If my turn boy [assistant] is not here and I leave, in 15 minutes some of my fuel is taken and cargo stolen.” Another truck driver told us: “We are tracked by GPS by our companies. If I go off one road, we get a call from the company.”

Recognizing the difficulty for truck drivers to access its clinics, North Star developed an outreach strategy. Each week, HIV testing counsellors visit truck drivers during their breaks or while they park overnight at a border crossing. A HIV testing counsellor in Salgaa, Kenya notes: “most of the time we need to do outreach and do HIV tests in the truck drivers’ cabins. Most of them will not come to the clinic.” North Star notes that its clinic teams along the transportation corridors must conduct regular behaviour change and communication sessions in nearby communities in order to meet their target volumes, typically aiming for 25-30 clients per day per clinic.

Operation ASHA

By establishing tuberculosis clinics where there is significant foot traffic by base of the pyramid consumers, Operation ASHA address many of the critical demand side factors that prohibit people from seeking and adhering to TB treatment, such as transportation and time travelling to and from clinics. Patient convenience, community mobilization, and comprehensive counselling form core elements of Operation ASHA’s services (Center for Health Market Innovations, 2016). Providing convenience for customers in accessing TB treatment is a crucial aspect of Operation ASHA’s model given that promoting adherence to TB is often challenging (Makanjuola, Taddese and Booth, 2016).

These two examples highlight the point that, for social enterprises targeting lower-income consumers, it is often necessary to adjust offering to meet patient demand in order to achieve goals of the last stage of the value chain, which focuses on the delivery of a health product or service. The Operation Asha example illustrates how adapting services to the needs and interests of local populations is critical for scaling success. The North Star case emphasizes that targeting different types of mobile populations from truck drivers and sex workers requires understanding local realities and constraints.

Despite the successes, health services organizations also face major issues with VCI strategies. Below we discuss cases from our sample in which organizations confronted scaling challenges.

Pitfalls in Value Chain Integration

Failure to create effective partnerships for key resources can constrain an organization’s expansion goals.

Penda Health

In Kenya, Penda sought to expand its presence in Machakos, near Nairobi. While factories in the area were keen to have Penda offer its services to their employees, the partnerships fell through because Penda could not find an appropriate location for a clinic. Penda told us: “…we thought we had secured the perfect location for partnering with many of the factories in that area, but illegal actions by the landlords there caught us off-guard and, after a protracted struggle, we withdrew from this location.” Penda further noted: “We learned that finding a location, is very, very hard, so you should start with a location and then find the community partners nearby. Or, have the community partner give you space.” This example illustrates how external actors can undermine expansion efforts. Penda secured a partnership to attract a paying clientele, but was unable to realize the gains from this partnership because it could not identify partners at another stage of its value chain, procuring real estate.

North Star

Attracting paying clients forms a key value chain stage for most of our cases. In Kenya, North Star Alliance learned it is not always possible to exploit revenue-generating opportunities due to scale barriers that lie outside the boundaries of the organization. North Star has developed partnerships with several transport companies, many of which were willing to provide contracts for North Star to conduct annual medical check-ups for their long-haul truck drivers. A manager from Roy Hauliers, which manages a fleet of 250 long-haul truck drivers, told us: “we wanted to give North Star this business so they could do the medical check-ups of our drivers.” North Star was keen to take advantage of the opportunity. However, its clinics are staffed by clinical officers or nurses, but the Ministry of Health guidelines stipulated that check-ups require a doctor. The inability to manage regulatory barriers in North Star’s ecosystem limited its ability to create an alternative revenue stream.

Conclusion

This study offers suggestive analysis of how private sector ventures that target the base of the pyramid in health services delivery use value chain integration strategy. We argue that adopting VCI strategy combined with enabling strategies of an efficiency core and four types of management capabilities helps social enterprises increase their scale.

The ability of health services organizations to draw resources from disparate partnerships with government and private sector actors along different stages of their value chains is central to scaling success. Partnerships along a venture’s value chain are critical precisely because many of the scale barriers lie outside the boundaries of social enterprises. Our research emphasizes why VCI strategy and the enabling strategies of efficiency core and management skills matter for scaling health services delivery to the base of the pyramid.

The study has limitations that require additional research. Our sample is relevant, but small. We omit some value chain partnerships that we were not able to derive from published data and interviews. Further research comparing organizations that adopted a VCI strategy to those that did not would yield valuable insights. Moreover, inquiry is needed on how social enterprises coordinate their value chain partnerships.

The study offers insights on how social enterprises pursue value chain integration. By using VCI strategy as a practical framework, our research illustrates how and why the broader ecosystem matters for scaling success. The core point is that partners not directly involved in an organization’s core mission can advance or thwart long term success. Hence, global health organizations need to pay close attention to value chain integration strategy and its enabling activities.

References

- Acumen Fund. Ziquitza Healthcare Limited. https://www.healthyentrepreneurs.nl/our-concept/. Accessed August 10, 2017.

- Adner R. Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harvard Business Review. 2006;84(4):98-107;148.

- Bhattacharyya O, Khor S, McGahan A, Dunne D, Daar A, Singer P. Innovative health services delivery models in low-and-middle-income countries: what can we learn from the private sector? Health Research Policy and Systems. 2010;8(24):1-11.

- Stanford Graduate School of Business. Riders for Health: Prospective Trial Results from Southern Province Zambia. https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/sites/gsb/files/files-fpp/22766/research-briefing-riders-for-health.pdf. Published October 2014. Accessed January 15, 2018.

- Capron L, Mitchell W. (2013). Build, borrow, or buy: Solving the growth dilemma: Boston, MA; Harvard Business Press: 2012.

- Chandy L, Hosono A, Kharas H, Linn J. Getting to scale: how to bring development solutions to millions of poor people. Washington, D.C.; Brookings Institution Press: 2013.

- Cooley L, Kohl R. Management Systems International. Scaling up from vision to large scale change: a management framework for practitioners. http://www.msiworldwide.com/wp-content/uploads/MSI-Scaling-Up-Framework-2nd-Edition.pdf. 2012.

- Feller A, Shunk D, Callarman T. Value chains versus supply chains. http://www.stephbti.ac.in/notes/33171-value-chain-vs-supply-chain.pdf. BPTrends. March 2006.

- Hassey K, Kassalow JS. Stanford Social Innovation Review. VisionSpring Aims to Provide Eyeglasses to Millions. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/visionspring_aims_to_provide_eyeglasses_to_millions. Published May 29, 2014. Accessed January 1, 2018.

- Healthy Entrepreneurs. Our Concept. https://www.healthyentrepreneurs.nl/our-concept/. Accessed October 16, 2017.

- Healthy Entrepreneurs. Healthy Entrepreneurs. http://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/healthy-entrepreneurs. Accessed on October 20, 2017.

- Health Innovations. 3 Lessons from Partnering with Factories in Kenya. http://www.pendahealth.com/index.php/component/easyblog/entry/3-lessons-from-partnering-with-factories-in-kenya?Itemid=435. Accessed July 15, 2017.

- Jacaranda Health. Jacaranda’s Model.https://jacarandahealth.org/maternity-in-east-africa/jacarandas-model/. Accessed on July 10, 2017.

- Kim JY, Farmer P, and Porter ME. Redefining global health-care delivery. Lancet. 2013;382:1060-1069.

- Koh H, Hedge N, Karamchandani A. The Rockefeller Foundation. Beyond the Pioneer: Getting Inclusive Industries to Scale. https://assets.rockefellerfoundation.org/app/uploads/20140508153451/Beyond-the-Pioneer-Report.pdf. Published April 2014. Accessed Janaury 1, 2018.

- Kramer MR, Pfitzer MW. The ecosystem of shared value. Harvard Business Review. 2016;94(10):80-89.

- Lifenet International. The Model. http://www.lninternational.org/what-we-do/model/. Accessed from July 10, 2017.

- Makanjuola T, Taddese HB, Booth A. Factors Associated with Adherence to Treatment with Isoniazid for the Prevention of Tuberculosis amongst People Living with HIV/AIDS: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Data. PLoS One. 2014;9(2): e87166.

- Mangham LJ, Hanson K. Scaling up in international health: what are the key issues? Health Policy and Planning. 2010;25(2):85-96.

- Mitchell W. Why Apple’s product magic continues to amaze–skills of the world’s# 1 value chain integrator. Strategy & Leadership. 2014;42(6):17-28.

- Operation Asha. Tubercolosis. http://www.opasha.org/our-work/our-operation/. Accessed July 13, 2017.

- Porter ME. Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. New York, NY: FreePress; 1985.

- Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining health care: creating value-based competition on results. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2006.

- Simmons R, Fajans P, Ghiron L (Eds.). Scaling up health services delivery: from pilot innovations to policies and programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

- Sutherland M, Krige K. .Unjani “clinics in a container”: social franchising in South Africa. Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1108/EEMCS-06-2016-0151.

- Unjani Clinics. Unjani Clincs. http://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/unjani-clinics. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- VisionSpring. VisionSpring’s Distribution Channels. http://visionspring.org/distribution-channels/. Accessed September 13, 2017.

- Wong J, Zlotkin S, Ho C, Perumal N. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Replicating Parts, not the Whole to Scale. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/replicating_parts_not_the_whole_to_scale. Published August 7, 2014. Accessed January 1, 2018.

- Yamey G. What are the barriers to scaling up health interventions in low and middle income countries? A qualitative study of academic leaders in implementation science. Globalization and Health. 2012;8(11).

Websites

- Acumen Fund. (2017, August 10). Ziquitza Healthcare Limited. Retrieved from: https://www.healthyentrepreneurs.nl/our-concept/

- Healthy Entrepreneurs. (2017, October 16). Our Concept. Retrieved from: https://www.healthyentrepreneurs.nl/our-concept/

- Health Entrepreneurs. (2017, October 20). Healthy Entrepreneurs. Retrieved from: http://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/healthy-entrepreneurs

- Health Innovations. (2017, July 15). 3 Lessons from Partnering with Factories in Kenya. Retrieved from: http://www.pendahealth.com/index.php/component/easyblog/entry/3-lessons-from-partnering-with-factories-in-kenya?Itemid=435

- Jacaranda Health. (2017, July 10). Jacaranda’s Model. Retrieved from: https://jacarandahealth.org/maternity-in-east-africa/jacarandas-model/

- Lifenet International. (2017, July 10). The Model. Retrieved from: http://www.lninternational.org/what-we-do/model/

- Operation Asha. (2017, July 13). Tubercolosis. Retrieved from: http://www.opasha.org/our-work/our-operation/

- Unjani Clinics. (2017, September 20). Unjani Clincs. Retreived from: http://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/unjani-clinics

- VisionSpring. (2017, September 13). VisionSpring’s Distribution Channels. Retrieved from: http://visionspring.org/distribution-channels/