Lilac Nachum, PhD, City University New York, Baruch College [1]

Contact: lilac.nachum@baruch.cuny.edu

What is the message?

How the balance between the global and the local is transforming the scope of opportunities and raising challenges for healthcare professionals and institutions.

What is the evidence?

This paper is derived from a course on the globalization of healthcare developed and taught by Professor Nachum as part of Baruch College MBA program for Healthcare professionals. It is based on a variety of secondary sources and was informed by class discussions with the healthcare professionals enrolled in the course

Submitted: March 19, 2018; accepted after review: June 15, 2018

Cite as: Lilac Nachum. 2018. Healthcare: An Industry Unlike Any Other Goes Global. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 3, Issue 2.

The Globalization of Healthcare

The healthcare industry[2] has been transformed in recent years from what was traditionally a primarily domestic industry into an increasingly global industry, defined by cross-national principles. In parallel to the forces that have driven the globalization of the industry, however, there have been others that have resisted these developments and anchored the industry in national systems of healthcare delivery and consumption. This interplay between the global and the local is emerging as a predominant feature of the industry that is shaping its contemporary dynamics and will have significant consequences in the years to come. In this paper, I seek to explicate this development and examine the opportunities and challenges that it holds for healthcare providers and the policymakers who oversee the industry.

Healthcare: An Industry Unlike Any Other

The healthcare industry is distinctive in at least three ways. For one, in contrast to most other industries in which the ultimate goal of firms is profit-maximization, in healthcare this goal often poses a challenge to value creation through quality care. As an industry whose value creation lies in extending lives and enhancing their quality, there is a strong moral dimension attached to value creation, producing a delicate balance between this imperative and the different and often conflicting demands of economic performance and survival. Notwithstanding notable successes in combining value creation with financial goals, these goals often conflict with each other and impose tradeoffs. The vague notion of what is to be maximized challenges the development of performance measurement and creates scope for different points of view as to the appropriate indicators that should be used.

Further, the industry is characterized by distinctive structural issues. The consumers – patients with symptoms – are typically ignorant about the cause of their symptoms and the required treatment for relieving them; the suppliers – healthcare professionals, in affiliation with healthcare institutions or on their own, who diagnose the cause of the symptom, prescribe the treatment and may implement it – are, at least in the developed world, typically not paid by the consumers. Rather, market transactions involve one and often more intermediaries who administer the payment.[3] These intermediaries themselves vary in terms of their goals, agency and power, and their impact on the engagement between the healthcare provider and the patient receiving treatment.

Lastly, the healthcare industry stands out in terms of the demand for its output. Given the complex structure of the industry, identifying the actual source of demand is a challenge as it includes the patient, the doctor who prescribes the treatment and may implement it, and the payer for the service (at least in countries where the payers and the customers are two separate entities). Demand is often inelastic (what is the monetary value of life?) and is prone to information asymmetries of numerous kinds that influence the transactions and place much power in the hands of the intermediaries who pay for the service.

The distinctive attributes of the healthcare industry assume additional complexity as the industry globalizes. The ambiguity regarding the ultimate goal of healthcare, along with the subsequent difficulty of devising corresponding performance measures (notably whether performance should be measured by financial indicators, quality of care, outcome of treatment, or other metrics), are magnified by country-specific philosophies of life and mortality and varying perceptions regarding universal access. The United Nations (UN) Universal Declaration of Human Rights has long declared access to healthcare a basic human right: ‘everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care’.[4] Although more than half a century old, this assertion has not been adopted by all countries that are members to the UN in a comprehensive way. Variations in moral philosophy surrounding healthcare and the extent to which it is seen to be a universal right introduce stark differences in the healthcare industry across countries. These variations are reinforced by varying views of human ability to influence life quality and longevity versus those of faith and religion, including different perceptions of the value of life itself.

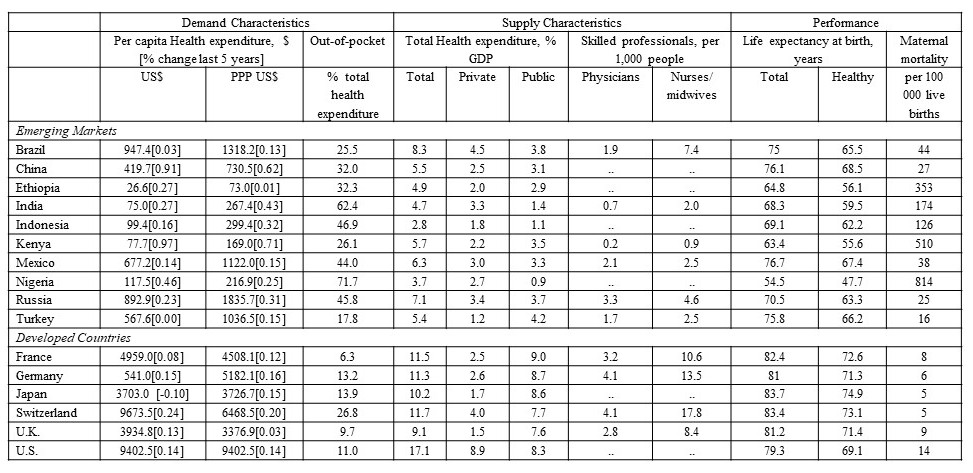

These philosophical and cultural differences bring about varying views as to who should be responsible for healthcare provision and who should pay for it. The UN International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights assigned the responsibility for the provision of healthcare to national governments: ‘[every nation is responsible for] ‘the creation of conditions which would assure, to all, medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness’. [5] But this declaration has not been universally practiced. The size adjusted government expenditure on healthcare varies enormously across countries (Table 1). Country-specific approaches differ in terms of the ultimate provider and payer for healthcare, whether private or public, or as is the case in many developing countries – by the consumers. There are also considerable country differences in terms of access to healthcare services and its coverage. As the data in Table 1 show, out-of-pocket payment accounts for up to three quarters of total healthcare expense in countries such as Nigeria and India, but represents around a tenth or less of the total in many developed countries. These variations are accentuated by differences in the level of economic development and that affect the availability and quality of services (Table 1).

Table 1. Selected Healthcare Indicators by Country

Latest available: 2014-2016

WHO, World Health Statistics http://who.int/entity/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2017/en/index.html; World Bank Development Indicators Database

Country differences also express themselves in the nature of demand. Varying perceptions of healthcare versus healing by forces of faith and religion, coupled with different views of modern versus traditional medicine, often determine the level of demand for healthcare services and its nature. In addition, education levels influence information asymmetries between participants in the complicated transactions that define the industry. Lastly, differences in life style, diet, and other ongoing activities affect the types of diseases prevalent across countries and their frequency.[6] The data in Table 1 show vast variations in per-capita healthcare expenditure, indicative of these differences in the demand for healthcare across countries. In the following sections I discuss how the tension between the global and the local is shaping the nature of supply and demand for healthcare around the world.

The Tension between the Global and the Local: Demand and Supply for Healthcare Services

The forces that are driving the healthcare industry to become increasingly global and those that connect it to national systems manifest themselves within the framework described above. They are apparent in relation to both the demand for healthcare services and its supply. On the one hand, major participants in the healthcare industry, including healthcare professionals and institutions, drug producers, and consumers, have become more mobile, drawing healthcare delivery and consumption into global networks of interactions. At the same time, cultural, institutional, and behavioral differences continue to anchor the industry to different countries and arrest globalization.

Global and Local Demand

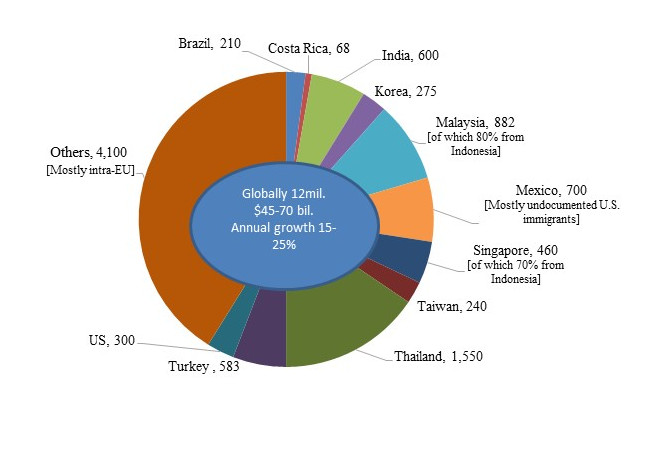

A major development that has globalized demand for healthcare is what has come to be known as ‘medical tourism’, that is, the travel by patients for medical treatments to other countries. While this phenomenon has existed for decades and by some accounts centuries, until recently it was small and confined to wealthy people from developing countries traveling to Western countries for medical treatment. What is new is the recent emergence of medical tourism from developed countries to emerging markets (Figure 1), driven by the development of local healthcare institutions in emerging markets and improvement in the quality of their healthcare services.

Figure 1. Medical Tourism

Destination countries by number of patients (in thousands), 2015

Patients Beyond Borders, http://www.patientsbeyondborders.com/medical-tourism-statistics-facts

Based on estimates by Deloitte, McKinsey, Gallup, the Economist, host countries health and tourism ministries

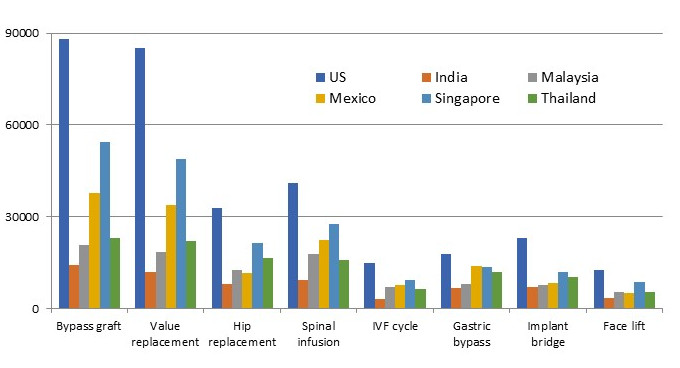

These institutions offer medical services for a fraction of the costs in developed countries (Figure 2) and minimal waiting time.[7] Combining a low-cost labor force with efficient delivery, assisted by state-of-the-art technology, hospitals in emerging markets have managed to cut costs and shorten delivery time to levels unimaginable in the developed world.[8] Accreditation by U.S. and Global Accreditation Associations provides quality assurance for patients and payers, and have removed major obstacles for the growth of medical tourism. By 2016 more than 600 hospitals worldwide were accredited by the Joint Commission International Accreditation, a number that has been growing by about 20% annually[9]. In 2015 medical tourism amounted for an estimated $40-$75 billion worth of economic activity, or about 1% of global healthcare expenditure.

Figure 2. Cost Variations of Medical Procedures

US$: 2015

Patients Beyond Borders

The development of medical tourism has captured the attention of healthcare insurance services in the developed world. Large U.S. insurers have examined these offshore developments as low-cost alternatives for U.S. services, and some have incorporated them in their offerings. Britain’s NHS is considering partnerships with leading players in India and Thailand as a way to cut waiting times.

The growth in medical tourism suggests that at least in the short term, it offers solutions to limitations of healthcare systems in developed countries (i.e., high costs in the U.S. and long waiting lists in Europe). The long-term impact of this development on progress in addressing the causes that generate the demand for medical tourism is unclear. It appears likely that in the mostly privately-owned U.S. industry, competition from low-cost alternatives would create pressure for increased efficiency and lower costs, as I discuss in some detail below. This in turn could reduce demand for low-cost solutions elsewhere. The response of the government-owned healthcare system is Europe is more difficult to predict, as it less likely to be subject to market forces. European governments may opt for using medical tourism as a low-cost alternative that enables reduction of government resources allocated for healthcare rather than adding capacity to their local industries.

At the same time that demand for healthcare continues to expand globally, the type of demand varies significantly across countries, reflecting for the most part country variations in the prevalence of diseases. For instance, the number one cause of death in the developed world is heart disease, accounting for more than 12% of total deaths, whereas in mid- and low-income countries most deaths are caused by cerebrovascular disease (14%) and respiratory infections (11%).[10] Likewise, the incidence of cancer is three times higher in China than in India. The disparity in Africa is even greater.[11]

Global and Local Supply

On the supply side, the major providers of healthcare, notably healthcare professionals, hospitals, and pharmaceutical and other med-tech companies, have vastly broadened their global reach in recent decades. Movement of healthcare professionals, predominantly from emerging markets to developed countries, is not new, but its magnitude has grown considerably, fostered by reduction in traveling costs and liberalization of immigration policies for healthcare professionals. Initially, nurses came most commonly from the Philippines, but more recently, their national origins have widen considerably.[12]

These developments have often been driven by mismatches between supply and demand that have proliferated around the world – according to the World Health Organization (WHO) by more than seven million healthcare professional providers in 2016, a number that is estimated to double by 2035. More than two-third of the 300 respondents to the American College of Healthcare Executives’ annual survey reported experiencing shortage of registered nurses and primary care physicians, and more than half noted shortage of specialized physicians.[13] Leading U.S. hospitals have been importing nurses since the 1980s in the face of a large nursing shortage.

The movement of doctors across countries has also been prevalent, although less common than that of nurses due to different qualification requirements. According to one estimate almost 40,000 Nigerian doctors practice outside Nigeria, three-quarter of them in the U.K.[14] Whereas for the most part, these moves are initiated by individuals seeking to further their careers and better their lives, in some cases they are assisted by governments. For instance, the Cuban government, under the auspices of the WHO, exports local doctors to Brazil, pays their salaries, and receives payment for their services from Brazilian authorities, turning these transfers into a major source of the government’s foreign currency.[15]

Industry has a longer track record of global expansion. Pharmaceutical companies, in particular, have long been global. The high cost of drug development that gives rise to vast scale economies, coupled with short spans of patent protection, have pushed pharmaceutical companies to expand the market for their drugs across the globe.

Most recently, hospitals, which were traditionally deeply grounded in particular localities, also have started to globalize. Leading hospitals in emerging markets are rapidly expanding overseas. India’s Apollo Hospitals Group, the largest private hospital group in Asia, operates 55 hospitals with 9,215 beds, and has facilities in India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Ghana, Nigeria, Mauritius, Qatar, Oman, and Kuwait, and plans for further global expansion. Only regulations have prevented it from entering the U.S. [16]. Some of the most prestigious U.S. hospitals, among them Johns Hopkins, Cleveland Clinic, Harvard, and Duke, have formed partnerships that offer combined treatments in the U.S. and overseas. Similarly, Canadian hospitals such as SickKids Children’s Hospital have begun to expand internationally.

The major barrier for the globalization of healthcare supply is country regulations. Doctors are tied to the locality in which they receive their medical training by varying qualification requirements that raise the cost of movement across countries. Foreign hospitals’ expansion is also limited by country restrictions, making this segment of the healthcare sector the least global. The share of FDI in healthcare services is a fraction of total service FDI in both developed and developing countries, although it registered substantial growth over the last decade. In an era where cross-border M&A activity has been mushrooming across industries, there has been almost no cross-border acquisitions of hospitals (although domestic mergers are common).[17]

U.S. hospitals and other healthcare providers have been among the world’s most active foreign investors, particularly in Latin America and the U.K.[18]. The Federation of America Hospitals lists almost a hundred overseas hospitals owned by U.S. major hospitals. However, there is no corresponding activities the other way around. For instance only regulations prevented Indian hospitals from establishing themselves in the U.S. Whereas countries around the world, most notably developing countries, have become increasingly open to foreign ownership of healthcare services, the U.S. has been highly restrictive.

Regulations and country variations have been a drag also on the global expansion of pharmaceutical companies. The regulatory environment that surrounds drug development, testing, and approval varies considerably around the world, undermining advantages of global scale. Varying levels of patent protection across countries are another challenge for the globalization of pharmaceutical companies, and variations in diseases and their prevalence impact global standardization of drug development.

Implications for the Healthcare Industry

As the home of some of the world’s most prestigious hospitals and healthcare professionals, developed country institutions and professionals are well-positioned to benefit from the globalization of the healthcare industry. Global developments increasingly make it possible to scale the reputation of hospitals and professionals globally and exploit them on a global scale. It enables local institutions in these countries to attract patients from around the world to their existing facilities and increase their share of the rapidly growing medical tourism. As emerging market consumers become wealthier, demand for high quality healthcare services in these countries is increasing, and could foster medical tourism to developed countries.

In addition to attracting patients to developed countries, these constituencies should also be able to expand their scope globally by establishing themselves overseas, by either direct investment or through various forms of partnerships with local providers in foreign countries. This process will vary according to the type of services provided and their comparative advantage in different countries.

Some reputable U.S. hospitals have recently been experimenting with such endeavors, and would likely pursue these further as a means to leverage on their expertise and increase market share. The Directory of U.S. Hospital Partnerships with Foreign Hospitals, published by the American College of Healthcare Executives and the American Hospital Association, lists dozens of partnerships. To qualify for inclusion in the Directory, partnerships need to be deep and comprehensive, and form ‘a cooperative and mutually beneficial relationship between a U.S. hospital and a hospital in a different country, … designed to facilitate the exchange of knowledge, technical information and other insights that contribute to improved healthcare services in both hospitals.’[19]

At the same time, global developments could also pose considerable challenges to hospitals and healthcare professionals in the developed world. The forces that enable them to broaden the potential market for their services also increase cost pressures and put them in competition with low-cost providers. These constituencies, notably in the U.S., have little experience in cost-driven competition and this could pose a serious challenge for them. The strongest impact of these forces will probably be felt in what are today the most lucrative parts of the industry, namely the highest cost operations and procedures. The high cost of these treatments compared to the emerging alternatives overseas will increase the incentives to travel elsewhere. These developments will put pressure to improve the consumer experience (for instance, by providing rehabilitation facilities for medical tourists and accommodation for accompanying relatives) and at the same time cut costs in order to stay competitive.

The challenge for these constituencies lies in designing strategies that are responsive to the tension between the global and the local that I outlined in this paper, and take advantage of them by articulating the appropriate balance, considering their distinctive sources of strengths and weaknesses. The rewards for doing this properly are vast.

References

- This paper is derived from a course on the globalization of healthcare developed and taught by Professor Nachum as part of Baruch College MBA program for Healthcare professionals. An earlier version of this paper appeared as Baruch College’s Weissman Center Occasional Paper, 2018. The author acknowledge with deep gratitude the excellent comment of the Editor during the review process.

- The health care industry is defined broadly to include health care professionals (e.g., doctors, nurses), healthcare institutions (e.g., hospitals), pharmaceutical companies, and producers and suppliers of equipment for healthcare.

- This is the common practice in developed countries. In developing countries large share of healthcare costs is covered by the consumers, as will be discussed below.

- Article 25, 1948

- Article 12, 1966

- Farmer et al., Reimagining Global Healthcare: An Introduction. 2013; Holtz C. (ed.), Global Health Care: Issues and Policies. 2017; Reid, The Healing of America: A Global Quest for Better, Cheaper, and Fairer Health Care. 2010.

- Siciliania, Moranb and Borowitz. Measuring and comparing health care waiting times in OECD countries. Health Policy, December 2014

- Wall Street Journal, The Henry Ford of Heart Surgery: a Factory Model for Hospitals. November 25, 2009; Hub and Spoke, HealthCare Global. Harvard Business School Case #313030, 2015.

- Joint Commission International https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/about-jci/jci-accredited-organizations/

- World Health Organization (WHO), The Global Burden of Disease Project.

- International agency for research on Cancer, http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx

- Brush et al., Imported Care: Recruiting Foreign Nurses to U.S. Health Care Facilities. Health Affairs 2004

- http://www.ache.org/pubs/research/ceoissues.cfm

- https://www.vanguardngr.com/2017/12/medical-tourism-ambode-harps-retraining-medical-practitioners/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/29/world/americas/brazil-cuban-doctors-revolt.html?_r=1

- Health City Cayman Islands. Harvard Business School Case #714510, 2014.

- Holden, C. The Internationalization of Corporate Healthcare: Extent and Emerging Trends. Competition & Change, 2005, 9(2), 185-203; Holden, C. The Internationalization of Long Term Care Provision. Global Social Policy, 2002, 2(1), 47-67; Herman L. Assessing International Trade in Healthcare Services. The European Centre for International Political Economy Working Paper No. 03/2009, Brussels 2009.

- Jasso-Aguilar, R. et al. Multinational corporations and health care in the United States and Latin America: strategies, actions, and effects. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour, 2004, 45, 136-157.

- https://www.ache.org/foreignhospitaldirectory.cfm