Navid Asgari, Assistant Professor, Gabelli School of Business, Fordham University; Will Mitchell, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Contact: William.mitchell@rotman.utoronto.ca

Abstract

What is the message?

Value chain integration in the U.S. pharmaceutical ecosystem is shifting from leadership by pharmaceutical manufacturers to a major role for three-part configurations of specialty pharmacies, healthcare insurers (payers), and pharmaceutical benefit managers, which we refer to as PPP combinations. During the past half decade, these PPP combinations have gained negotiating power relative to manufacturers, with the potential to influence both pharmaceutical net prices and complementary “beyond the pill” strategies. The ongoing disruptions might put manufacturers at risk or, instead, may improve the ability of actors in the system to work together to design and implement complementary services that lead to improved health outcomes and greater cost effectiveness in the healthcare system.

What is the evidence?

The analysis uses data concerning revenues, profits, entries, and acquisitions in the pharmaceutical ecosystem between 1999 and 2019. We consider five types of actors: pharmaceutical manufacturers (both major biopharma and moderate pharma), health insurers, wholesalers, pharmacies, and pharmaceutical benefit managers (PBMs).

Submitted: May 3, 2020; accepted after review and revision: May 20, 2020

Cite as: Navid Asgari and Will Mitchell. 2020. The Evolution of Value Chain Integration in the U.S. Pharmaceutical Ecosystem. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.hmpi.org), Volume 5, Issue 2. Spring 2020.

The Pharmaceutical Ecosystem in the U.S. is Complex

The pharmaceutical industry continues to attract both criticism and, with the threat of the coronavirus, hope for innovative tests, treatments, and vaccines. Although most attention is targeted at pharmaceutical manufacturers, the pharmaceutical ecosystem is much more complicated than simply manufacturers. To bring drugs from development to consumers also requires a sophisticated ecosystem of providers, wholesalers, payers, pharmacies, and pharmaceutical benefit management (PBM) services.

This article highlights the growing complexity and sophistication of the pharmaceutical ecosystem, while comparing revenue growth and profitability trends in different parts of the sector. We emphasize the current strategic challenge of determining which actors will be the value chain integrators that shape the evolution of the sector and distribution of profits within it.

A recent trend is the emergence of combinations of specialty pharmacies, payers and PBMs, whether within single firms or as alliances. [1] These PPP combinations are now competing with pharmaceutical manufacturers to be the value chain integrators that lead and shape the sector.

Actors in the Pharmaceutical Ecosystem

Seven categories of major actors

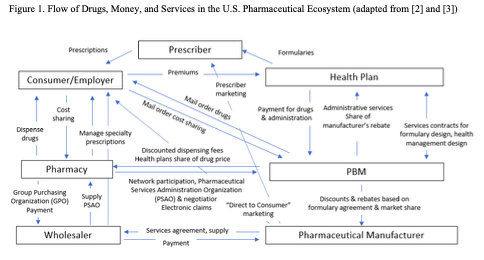

Figure 1 depicts a simplified version of relationships among seven actors in the pharmaceutical ecosystem: consumers, prescribers, manufacturers, wholesalers, pharmacies, health insurer payers, and PBMs. To maintain clarity, the figure omits other key actors such as firms and institutes that focus on drug discovery; contract research organizations and contract manufacturers; regulatory agencies; and academic institutions. Even with this simplification, the flow of drugs, money, and services that the figure depicts is complex.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers: Historically, drug companies based in North America, Europe, and Japan were the leaders of the pharmaceutical ecosystem. They developed drugs and/or acquired them from partners; brought them through the regulatory system; produced and/or coordinated production; set list prices; marketed their benefits to prescribers; and largely coordinated the flow of drugs through the system. In the past thirty years, however, as pharmaceutical prices have risen and drug regimens have become more complicated, other actors in the system have increased their power.

Wholesalers: Drug wholesalers such as McKesson, Cardinal, and AmerisourceBergen have long been visible players in the ecosystem, with a primary role in distributing drugs to hospitals and pharmacies. With the growth of biological and other complex medicines in the past two decades, the major wholesalers commonly also offer services required to help clinicians, insurers, and consumers prescribe, use, and pay for specialty pharmaceuticals.[i]

Pharmacies: Pharmacies such as CVS, Walgreens, and Rite Aid have a long-standing role in dispensing drugs. More recently, they have taken on more sophisticated activities involving group purchasing organizations and managing prescriptions for specialty pharmaceuticals.

Health insurers: Third-party health insurers such as UnitedHealth, Humana, Aetna, Cigna, Anthem, and Centene receive premiums from consumers and/or their employers, then manage payment for drugs. Like wholesalers and pharmacies, health insurers also commonly offer services for specialty pharmaceuticals.

Pharmacy benefit management services: PBMs began during the 1960s, primarily as mail-order services. During the past half century, they have become highly sophisticated – negotiating discounts with manufacturers that they in part pass on to payers; designing formularies and health management programs; providing administrative services to pharmacies and insurers; and organizing service networks.

Prescribers: Physicians and other prescribers traditionally were the primary actors in deciding what drugs were relevant for their patients, paying only limited attention to drug prices. During the past two decades, however, as drug prices have soared and pharmaceutical treatments have become part of multi-faceted health management regimens, insurers and PBMs have increasingly influenced providers’ prescription choices via formulary placement.

Consumers: Patients traditionally were “drug takers”, largely following the advice of their prescribers. Since at least the mid 1990s, though, patients have increasingly become decision-making consumers. Multiple trends have led to greater consumer agency, including the growth of direct to consumer marketing; access to on-line information about conditions and treatments; and the availability of mail and on-line channels for obtaining drugs.

Who are the value chain integrators?

This is a complex ecosystem. One of the learnings from strategic management research is that complex systems do not manage themselves. Instead, they benefit from having value chain integrators (VCIs) that coordinate activities throughout the system. [5] VCIs tend to shape the evolution of an industry and gather a substantial share of revenue and profits.

Historically, pharmaceutical manufacturers have played the VCI role in the pharmaceutical ecosystem. Over the past twenty years, though, there has been a substantial shift in power and revenues among the actors, as well as intriguing trends in profitability and corporate combinations that hint at ongoing changes in VCI power. We next report revenue and profitability trends. We then turn to the evolution of PBM entry ownership and to corporate combinations of insurers, specialty pharmacies, and PBMs.

Pharmaceutical Ecosystem: Revenue and Profitability Trends

Revenue trends

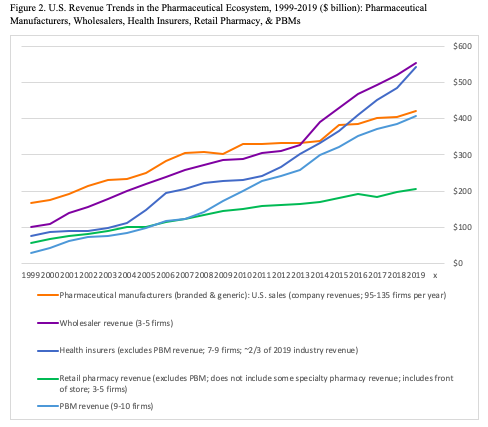

Figure 2 reports trends in U.S. revenue for five types of commercial actors in the pharmaceutical ecosystem: pharmaceutical manufacturers, wholesalers, health insurers, retail pharmacies and PBMs. The revenue data encompass most major players in each of the five categories from 1999 to 2019, including 18 PBMS, ten health insurers,[ii] five pharmacy chains, five wholesalers, and 154 pharmaceutical manufacturers.[iii] We obtained data from corporate annual reports and analyst discussions. The appendix lists the firms in the data.

Two points stand out in Figure 2. First, total revenue has grown massively in the past two decades. In 1999, total revenues across the five categories reached just over $400 billion. In 2019, the sum of the five categories exceeded $2.1 trillion: almost 5x growth in 20 years.

One must be careful here: the sums involve overlapping revenues as activities pass from one type of actor to another, so that the total substantially overstates the impact on pharmaceutical-related health expenditure in the country. Moreover, the health insurer total includes expenses other than pharmaceuticals, including med tech and medical services. Nonetheless, there is an unambiguous major increase in healthcare expenditure in the pharmaceutical ecosystem over the past two decades.

Second, in 1999, pharmaceutical manufacturers dominated the sector, with net revenues that accounte for almost 40 percent of the summed expenditure ($169 of $432 billion). By 2019, though, wholesalers and health insurers had passed the manufacturers and PBMs were close behind. Retail pharmacies (excluding their PBM revenue) lagged substantially at about $200 billion although this number is somewhat ambiguous about their pharmaceutical impact, because it includes sales of “front of store” consumer items but omits some of the companies’ specialty pharmaceutical service revenue. On a revenue basis, therefore, pharmaceutical manufacturers now share ecosystem leadership with insurers, wholesalers, and PBMs.

Profitability trends

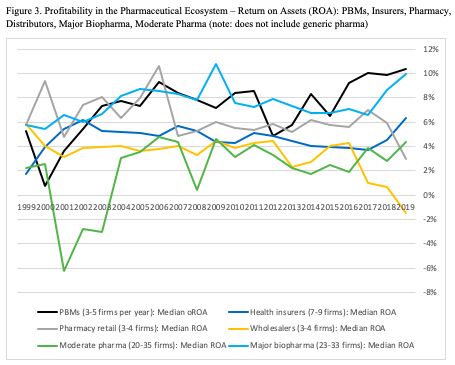

The next question is who is profiting from this activity? Figure 3 reports profitability trends for the categories based on return on assets (ROA). The comparison splits out the pharmaceutical manufacturers into major biopharma firms (e.g., Merck, Janssen, Sanofi, Roche, Takeda, Astellas, Amgen, Biogen) and moderate pharmaceutical firms (e.g., Valeant, Shire, UCB).[iv] The ROA trends are based on data from ten health insurers, four pharmacy chains, four wholesalers, eight PBMs, 39 moderate pharma firms, and 35 major biopharma firms.

Trends across ecosystem categories in Figure 3 need to be compared cautiously, for two reasons. First, the data include corporate return on assets (ROA) from five categories (insurers, pharmacy retail, wholesalers, moderate pharma, major biopharma), while using operating return on assets (oROA) for PBMs. The oROA calculations (typically based on earnings before taxes as a ratio of reported segment assets) will somewhat overstate final profitability but are relevant for activities within corporations that report segment-level revenues but do not report post-tax profits for the segments, which is the case for PBMs.

Second, the two pharmaceutical categories report global profitability because the firms rarely break out geographic profits (revenues for the other four categories are almost entirely from the U.S.). Hence, the within-category trends are somewhat more relevant than across-category comparisons, although substantial differences between categories are meaningful.

Three patterns stand out in Figure 3. First, although wholesalers may enjoy high revenue (Figure 2), they have the lowest profitability, with declining and even negative ROA over the past few years. Second, although there is substantial year-on-year variance within categories, the twenty-year trend is relatively stable. The major exception is the moderate pharma firms, which had negative median ROA in the early 2000s and now are moderately positive. Third, major biopharma firms and PBMs commonly lie at or near the top of the ROA range, particularly in the past few years.[v]

Currently, beyond the financial trends, the strategic question is whether the value chain integrator leadership will shift from pharmaceutical manufacturers to other types of actors. To begin to answer this question, it is useful to consider the evolution of PBM ownership over time, which the next section discusses.

The Evolution of PBM Ownership

PBM services over time

PBMs began in the 1960s largely as basic prescription mail order services. By the early 1990s, they had become more sophisticated and have become increasingly so. [2, 6-10] In 1993, for instance, the Diversified Pharmaceutical Services (DPS) unit within UnitedHealthcare expanded to manage the costs of UnitedHealth’s clients in delivering pharmaceutical benefit programs. These services included creating a pharmacy network and formularies for it; creating a pharmacy claims processing system; maintaining a prescription database; and negotiating discounts with pharmacy retailers and pharmaceutical manufactures. [11]

Today, these services form the backbone of modern PBMs. The PBM industry association, Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA), highlights cost reductions from providing home delivery; encouraging the use of generics on formularies (generics now exceed 90 percent of prescriptions in the U.S.); reducing waste; improving adherence to drug regimens; helping to create broad-based health management programs; managing expensive specialty drugs; and negotiating discounts with both pharmacies and manufacturers. [12] While services vary among PBMs, these are the core activities, with particular emphasis on negotiating discounts and rebates.[vi]

The expansion of PBM services has involved a wide range of entries, exits, and changes in corporate ownership. The appendix reports more than 60 PBMs that have operated during the half century between 1969 and 2020. Of those actors, 25 operate in 2020.[vii] Perhaps the two most notable features of the list are the ongoing pace of acquisitions in the industry and the varied types of actors that have attempted to operate PBMs.

PBMs and other actors in the pharmaceutical ecosystem

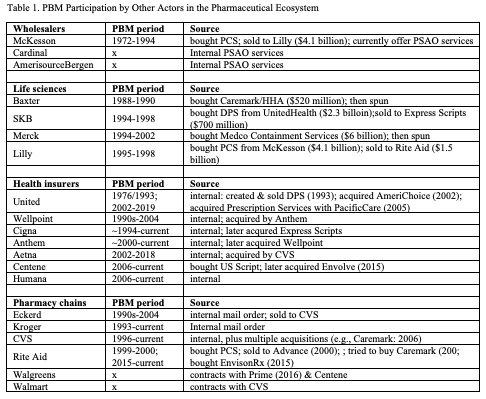

An important pattern arises with the types of actors that have operated PBMs. The four categories that we discussed earlier in this article are particularly notable: wholesalers; pharmaceutical manufactures and other life sciences companies; health insurers; and pharmacies. Over time, the wholesalers and pharmaceutical manufacturers have largely retreated, while health insurers and pharmacies continue to engage with PBM activity. Table 1 summarizes the participation.

Wholesalers: The pharmaceutical wholesaler McKesson purchased PCS, perhaps the first PBM (founded in 1969), in 1972 and continued to operate the unit for more than 20 years. By the 1990s, though, McKesson concluded that PCS did not fit well with its wholesale activities, in part because customers and federal agencies were concerned about potential conflicts between PBM strategy and wholesale contracts, and sold PCS to Eli Lilly in 1994. This marked the last time that a pharmaceutical wholesaler undertook full scale PBM activity as neither of the other two major wholesalers, Cardinal and AmerisourceBergen, have operated major PBMs. Nonetheless, all three major wholesalers do currently offer pharmacy services administration organization (PSAO) services that coordinate how independent pharmacies contract with insurers and PBMs.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers and other life science companies: Between the late 1980s and early 1990s, multiple life sciences companies entered the PBM industry. In 1987, Baxter was the first, purchasing Caremark/Home Healthcare of America (about $250 million revenues) out of independent ownership for about $528 million. Caremark’s major business at that time was home infusion and other home health services, while adding basic PBM support over time. In the 1990s, three major pharmaceutical manufacturers acquired PBMs. In 1993, SmithKlineBeecham purchased DPS (about $200 million revenue) from UnitedHealthcare for about $2.3 billion. Also in 1993, Merck purchased Medco Containment Services (about $1.8 billion revenues) for about $6 billion. In 1994, Lilly purchased PCS from McKesson (about $120 million revenues), for about $4.1 billion. Thus, the life sciences companies made substantial investments – particularly the three pharmaceutical companies – to enter the PBM market.

A major incentive for the acquisitions of PBMs by the pharmaceutical companies during the 1990s was a response to the first Clinton administration’s attempt to create a national healthcare system. Drug companies wanted to position themselves to negotiate prices if a public payment system emerged. It soon became apparent, though, that national health insurance was not going to be politically viable at that time. Moreover, the drug companies struggled to fit the PBM and pharmaceutical business models together. Challenges similar to those that led McKesson to sell its unit to Lilly, including Federal Trade Commission demands to maintain open formularies, limited the expected strategic benefits of combining pharmaceutical production with PBM intermediation.[9]

All four life sciences companies quickly exited the PBM business, sometimes with substantial losses. Baxter lasted three years, then spun off Caremark in 1990. Lilly sold PCS to Rite Aid for about $1.5 billion in 1998, far below the $4.1 billion it had paid three years earlier, when the anticipated strategic fits in pricing and formulary preferences did not materialize. SmithKlineBeecham sold DPS to a leading independent PBM, Express Scripts, for about $700 million in 1998, again far below the $2.3 billion price five years earlier. Merck spun off Medco in 2002 (ten years later, Express Scripts bought a much larger Medco for $29 billion by); in ten years of operations within Merck, the Medco PBM had declined from an independent business with more than 7 percent operating returns to a drug company subsidiary with less than 2 percent operating returns. Thus, neither the wholesaler McKesson nor the life sciences companies could find a successful fit between their core businesses and the PBM market.

Health insurers: Health insurers, by contrast with wholesalers and pharmaceutical companies, have been more successful in adding PBM services. UnitedHealth became the earliest of the major insurers to add a PBM when it created DPS in 1976. United sold DPS in 1993 but re-entered the PBM market when it acquired AmeriChoice in 2002 and then expanded through other acquisitions, including Catamaran in 2015. UnitedHealth’s OptumRx is now the third largest PBM in the country. Cigna created a PBM in about 1994, then expanded substantially to become the number two PBM when it acquired Express Scripts for $54 billion in 2018. The PBMs are now core part of the insurers’ business portfolios.

Other major insurers also have been active. Wellpoint created a PBM during the 1990s, then was acquired by Anthem in 2004. Anthem created a PBM about 2000, then expanded with the acquisition of Wellpoint four years later. Aetna created a PBM in 2002, which it operated until being acquired by CVS in 2018. Centene bought U.S. Script in 2006 and expanded with the acquisition of Envolve Health in 2015. Humana created a PBM in 2006, which is now the number four PBM in the country. At this point, all the major health insurers operate successful PBMs, creating effective matches between their insurance and PBM services.

Pharmacies: The major pharmacy chains also have been active with PBMs, though with more mixed success. Eckerd/JC Penney created a mail order PBM during the 1990s, which it sold to CVS in 2004 as part of Eckerd’s corporate dissolution. CVS launched a PBM in 1996 and then expanded through multiple acquisitions, including the purchase of Caremark in 2006, to become the largest PBM in the country. Rite Aid purchased PCS in 1999 only to sell it to Advance in 2000, then attempted to purchase Express Scripts in 2007 (losing the deal to Cigna), and finally re-entered with the acquisition of Envision in 2015. Some of the smaller pharmacy chains also are present. Kroger pharmacies, for instance, have operated a small PBM since about 1993. The other two major pharmacies, Walgreens and Walmart, do not operate substantial PBMs themselves but instead contract for PBM services: Walgreens with PBMs including OptumRX, Prime, and Centene; Walmart with CVS Caremark. Thus, the major pharmacy chains all engage with PBMs, either internally or via contracts, though only CVS has become a market leader.

The key point here is that PBMs are increasingly combining with insurers and/or pharmacies. These combinations are creating counterweights to the pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Tripartite Combinations: PBMs, Insurers, Specialty Pharmacies

PPP combinations

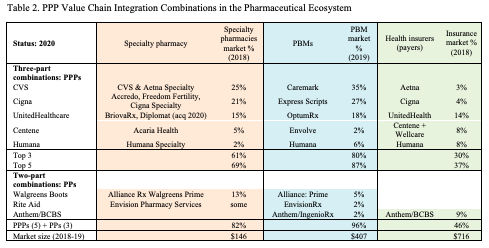

The convergence of PBMs with other actors in the pharmaceutical ecosystem has become even more extensive in the past half decade. The deals that we summarize above have led to a strong set of three-party PPP combinations, including PBMs, health insurers (payers), and specialty pharmacies. PBMs have been the linchpins in these combinations, linking services across the segments. Table 2 summarizes the current state of leadership across these three market segments.

Five corporate combinations dominate the cross-segment PPP positions in 2020. CVS owns Aetna and CVS specialty pharmacy services, the Caremark PBM, and Aeta insurance. Cigna offers multiple specialty pharmacy lines, the Express Scripts PBM, and Cigna health insurance. UnitedHealth has BriovaRx and Diplomat specialty pharmacy, the OptumRx PBM, and UnitedHealth insurance. Centene provides Acaria specialty pharmacy, the Envolve PBM, plus Centene and Wellcare insurance. Humana operates in the specialty pharmacy, PBM, and insurance segments. These five are major integrated players in the pharmaceutical ecosystem.

Several two-part PP combinations also have been created during the past five years. The pharmacy chain, Rite Aid, has operated in both the specialty pharmacy and PBM segments through its EnvisionRx service, acquired in 2016. The pharmacy chain, Walgreens Boots, has had an alliance with the Prime PBM since 2016 (Walgreens has also been in and out of insurance alliances with Anthem). The insurer, Anthem, also operates a PBM through its IngenioRx service, created in 2019. It is highly likely that the PP pairings will seek to add the third leg of the PPP tripod in the near future.

Together, as the table shows, five PPP and 3 PP combinations dominate much of the combined market. As of 2020, the eight amalgamations account for 82% of the 2018 specialty pharmacy market, 96% of 2019 PBM revenue, and 46% of 2018 health insurance revenue. In practice, these combinations are competing with the drug manufacturers to be the value chain integrators of the pharmaceutical ecosystem.

Disruption of traditional value chain integration

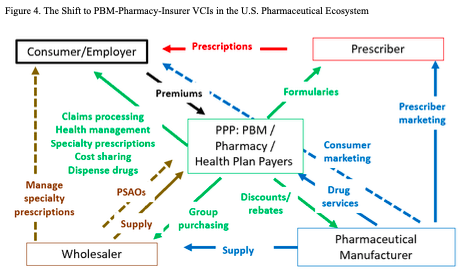

Figure 4 depicts the emerging relationships in the pharmaceutical ecosystem. The key point in the figure is that the PPP combinations are placing themselves at the center of the ecosystem. Pharmaceutical manufacturers continue to have substantial power. On the supply side, they bring new drugs to market. On the demand side, manufacturers continue to have meaningful market power in negotiating prices and services. The PPP combinations, though, now have substantial counter-balancing power as complementary value chain integrators.

Two major questions arise at this point, concerning prices and services. First, how extensively will PPP power bring down pharmaceutical profitability by negotiating even deeper discounts and rebates from list prices? While the major biopharma firms are comfortably profitable, on average, it would not take more than a moderate reduction in net prices to put this at risk, particularly for firms that tend to lie below the industry median profitability.[13] The moderate pharma firms, meanwhile, are even more at risk due to their lower average profitability. There is meaningful potential, therefore, for a substantial financially-driven disruption of the pharmaceutical manufacturer industry, particularly with the U.S. market accounting for about 40 percent of global pharmaceutical sales.

Moreover, because price reductions may be only partially passed on to consumers and their employers, there may be only limited concomitant financial benefits for end-users. Indeed, larger rebates commonly reflect higher list prices and service fees, again adding costs at multiple points in the system. [10]

Second, which players will take the lead in putting together bundles of services around pharmaceutical medicines. Players throughout the ecosystem are currently experimenting with multiple forms of complementary services, including pay for performance; infusion and other drug delivery support; compliance programs; nutrition and wellness programs; chronic disease management; patient tracking; and multiple forms of value-based healthcare designs. Some such services are integrated within existing players, while others involve partnerships with firms in other sectors, such as wearable devices; ingestible products; implantable devices; information technology providers; and artificial intelligence algorithms.

Such sets of complementary services have the potential to substantially improve health outcomes for consumers. They also may be able to increase cost-effectiveness by ensuring that expensive pharmaceuticals are used in the most effective contexts. Hence, beyond the pill innovations are critically important for the future of the pharmaceutical ecosystem, particularly for end-user consumers.

To date, beyond the pill strategies have had some effect but many attempts have taken hold more slowly than some expected. One of the reasons for the slow uptake has been the substantial fragmentation in the ecosystem that Figure 1 highlighted. A key question going forward is whether the more integrated ecosystem of Figure 4 will be more effective in designing and delivering such complementary strategies.

Two futures

There is no guarantee that the PPP configurations will be stable. Just as PBMs have moved in and out of other corporate configurations for the past half century, future misfits also are possible. Nonetheless, for the near term at least, the PPPs will affect competition, prices, and services in the pharmaceutical ecosystem.

Two near-term futures seem possible here. In one, leaders in the new ecosystem spends most of their efforts on price negotiations. In this first scenario, there is a lot to lose. The changes risk damaging the viability of pharmaceutical manufacturers, with no real gains in health outcomes. Moreover, even if the PPPs do negotiate deeper rebates, it is likely that only a limited amount of the reductions will reach consumers or their employers.[10]

In a second future, there is much more to gain. In this second scenario, the manufacturers and PPP combinations will find mutual benefit in working together to design and implement the complementary services that provide both cost effectiveness and improved health outcomes. Clearly, this is by far the superior path.

Looking Forward

The current challenge in the pharmaceutical ecosystem is to get past the historical obsession and political posturing about prices. Instead, we need to obsess about pursuing value in a way that respects the needs of each of the players in the system and, ultimately, the end user. Our primary goal needs to be creating strong cost-effective health value for consumers, with broad-based access to services.

Reaching this goal likely requires greater transparency of financial flows through the multiple parts of the pharmaceutical value chain. Perhaps counter-intuitively, the current lack of transparency does have benefits in maintaining the sustainability of the industry. It allows pharmaceutical manufacturers to negotiate higher net prices with some payers and so create price discrimination in which higher payers help cover the gap between average variable costs and average total costs that arise in the industry due to extensive need for fixed costs investments in research and related activities. [13] However, the extensive ambiguity in financial flows, partly reflecting the complexity of the sector and partly driven by confidentiality agreements between players, makes it difficult to evaluate what parts of the pricing chain are efficient, which mask systemic inefficiencies, and which reflect market power.

The current COVID-19 pandemic is teaching us about the importance of having a robust commercial life sciences sector, including pharmaceutical manufacturers. When we face crises such as this one, we need firms with the technical, organizational, and financial strength to respond in partnerships with public, non-profit, and academic actors across the globe. We also need sufficient clarity to be able to assess the robustness of the system.

The current shift to PPP value chain integration within the pharmaceutical ecosystem has the potential to either damage or strengthen the ability of life sciences companies to play the roles that we need them for. Reaching the positive potential will take thoughtful leadership by people throughout the ecosystem.

References

[1] Adam J. Fein. May 29, 2019. CVS, Express Scripts, and the Evolution of the PBM Business Model. Drug Channels. https://www.drugchannels.net/2019/05/cvs-express-scripts-and-evolution-of.html

[2] Patricia Danzon. 2015. Pharmacy Benefit Management: Are Reporting Requirements Pro- or Anticompetitive, International Journal of the Economics of Business, pages 245-261

[3] Economic Report on U.S. Pharmacies and Pharmacy Benefit Managers, 2017 [https://marketrealist.com/2017/10/walgreens-versus-cvs-discussing-pbm-strategies]

[4] Navid Asgari, Vivek Tandon, Kulwant Singh, and Will Mitchell. 2019. Dynamic Complementary Assets: Impact on Entrant and Incumbent Industry Leadership Duality. Working paper (available from the authors)

[5] Will Mitchell. 2014. Why Apple’s product magic continues to amaze–skills of the world’s #1 value chain integrator. Strategy & Leadership, 42 (6): 17-28, 2014.

[6] Robert F. Atlas 2004 The role of PBMs in Implementing the Medicare Prescription Benefit. Health Affairs, 23 (Supplement 1). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.W4.504

[7] Cole Werble. 2017. Pharmacy Benefit Managers. Health Affairs, September 14, 2017. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20171409.000178/full

[8] Helene L. Lipton, David H. Kreling, Ted Collins, Karen C. Hertz. 1999. Pharmacy Benefit Management Companies: Dimensions of Performance. Annual Review of Public Health. 20:361-401. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.361

[9] Kevin A. Schulman, L. Elizabeth Rubenstein, Darrell R. Abernathy, Damon M. Seils, Daniel P. Sulmasy. 1996. The effect of Pharmaceutical Benefit Managers: Is it being evaluated. Annals of Internal Medicine, 124: 906-913.

[10] Kevin A. Schulman, Matan Dabora. 2018. The relationship between pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and the cost of therapies in the US pharmaceutical market: A policy primer for clinicians. American Heart Journal, 206:113-122.

[11] UnitedHealthcare. 1994. Form 10-K, Annual Report to the Securities and Exchange Commission, page 6.

[12] Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA). https://www.pcmanet.org/the-value-of-pbms/ [accessed May 2, 2020]

[13] Will Mitchell. 2018. Pharma Prices Are Not Too High (Usually). Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 3, Issue 2.

[1] “Specialty pharmaceutical” is a recent designation of medicines that involve high-cost, complex development and production, as well as complicated administration to patients commonly involving injections or infusions. These can include drugs based on biologicals, complex small cell therapeutics, regenerative medicine, vaccines, therapeutic peptides, and others. Specialty pharmaceuticals typically are prescribed and administered by a limited set of medical specialists [4].

[2] The health insurer data include about 2/3 of 2019 industry revenue. Other health insurers include Kaiser, HSCS, and Guidewell; as mutual holdings, they do not report public financials. Several general insurers, including Prudential, John Hancock/Manulife, State Farm, and Allstate also have smaller health insurance portfolios.

[3] The 154 pharmaceutical manufacturers with revenue in Figure 2 include 55 major biopharmaceutical firms; 39 moderate pharmaceutical firms; and 60 primarily generic pharmaceutical firms with sales in the U.S. from 1999 to 2019. The firms were based in North America, Europe, or Asia. The figure reports estimates of U.S. revenues.

[4] The “moderate pharma” category includes firms that sell portfolios of branded drugs commonly in-licensed or acquired from other companies; although they are often referred to as “specialty pharma” firms we use the term “moderate pharma” in this article to distinguish them from “specialty pharmaceuticals”, which may be sold either by major biopharma firms or by moderate pharma firms. The appendix lists the firms in each category.

[5] We also calculated return on sales (ROS) and operating return on sales (oROS) for the firms in the six categories. The patterns are similar, other than substantially higher ROS for major biopharma firms; the extensive asset investment by these firms brings the apparent high profitability generated by sales (ROS) down to earth when net income needs to cover the firms’ asset investments (ROA).

[6] See, for instance, the 2002 10-K from Health Net (page 6), which highlights pharmacy benefit design; clinical programs; claims processing; appropriate medication; and discounts with retailers and manufacturers.

[7] Both the list of 60 and the current set of 25 PBMs are a subset of total PBM activity. Some analysts place the aggregate total during the life span of the industry at over 150 PBM programs, while the current total may reach close to 50 programs. Nonetheless, the figures capture the vast majority of major programs, both over time and currently. In 2020, the primary industry association, PCMA, reports 16 members, which together encompass most reported income for the industry (we are aware of only four PBMs operating in 2020 with at least moderate revenue that are not members of the PCMA; one of those, which is in our data, just entered the sector).

Appendix 1: Firms Included in Analysis Data

| A. PBMs in analysis data | Data period |

| Advance PCS (acquired by Caremark) | 2001-2003 |

| Anthem Wellpoint (contracted to Express Scripts) | 2000-2009 |

| Anthem/IngenioRx | 2019 |

| Catamaran / SXC (acquired by OptumRx) | 2008-2014 |

| Cigna | 1999-2019 |

| CVS | 1999-2019 |

| Envision Rx (Acquired by Rite Aid) | 2001-2014 |

| Express Scripts (acquired by Cigna) | 1999-2018 |

| Humana | 2009-2019 |

| Magellan Health / Magellan Rx | 2013-2019 |

| Medco Inc. (acquired by Express Scripts) | 2003-2012 |

| MedPartners / Caremark RX / AdvancePCS (acquired by CVS) | 1999-2006 |

| Merck Medco (spun into independence) | 1999-2002 |

| OptumRx (UnitedHealth) | 2005-2019 |

| PCS / Rite Aid (sold to Advance Paradigm) | 1999-2000 |

| Prime (BCBS) | 1999-2019 |

| Rite Aid / EnvisionRX | 2015-2019 |

| Wellpoint (acquired by Anthem) | 1999-2004 |

Note: Other PBMs operating during the 1999-2019 period (not in data) include Abarca; Accredo; Aetna (before being acquired by CVS); Argus; Catalyst; Centene/US Script/Envolve; CerpassRx; Diplomat; Eckerd; Envolve; First Health Group; First Health Coventry; Integrated Prescription Management; Kroger Prescription Plans; LDI; MaxorPlus; National Pharmaceutical; Navitus; Omnicare; PartnersRx; PerformRx; Pharmacy Gold; Prescription Solutions; ProAct; RxAdvance; Serve You; US Script; and WellDyneRx.

| B. Retail pharmacies in analysis data | Data period |

| CVS | 1999-2019 |

| Eckerd (acquired by CVS & Jean Coutu) | 1999-2003 |

| Jean Coutu / Brooks / Eckerd (U.S. operations acquired by Rite Aid) | 1999-2008 |

| Rite Aid | 1999-2019 |

| Walgreens | 1999-2019 |

Note: Other pharmacies operating during the 1999-2019 period (not in data) include Walmart, food and retail store pharmacies; and multiple small to mid-size pharmacies.

| C. Health insurers in analysis data | Data period |

| Aetna (acquired by CVS) | 1999-2018 |

| Anthem | 1999-2019 |

| Centene | 1999-2019 |

| Cigna | 1999-2019 |

| CVS / Aetna | 2019 |

| Humana | 1999-2019 |

| Molina | 1999-2019 |

| UnitedHealthcare | 1999-2019 |

| Wellcare (2020: acquired by Centene) | 2001-2019 |

| Wellpoint (acquired by Anthem) | 1999-2004 |

Note: Other insurers with health insurance coverage operating during the period (not in data) include HCSC; Kaiser; Guidewell; Allstate; Prudential; and John Hancock (Manulife)

D. Pharmaceutical wholesalers in analysis data |

Data period |

| AmerisourceBergen | 1999-2019 |

| Bergen Brunswig (merged with Amerisource) | 1999-2001 |

| Cardinal | 1999-2019 |

| Kinray (acquired by Cardinal) | 1999-2010 |

| McKesson | 1999-2019 |

Note: Henry Schein also distributed pharmaceuticals during the period.

| E1. Moderate pharmaceutical firms in analysis data | Data period |

| Abraxis | 2005-2019 |

| Acorda | 2001-2019 |

| Alkermes | 1999-2019 |

| Allergan | 1999-2014 |

| Allergan-Watson | 1999-2019 |

| AMAG | 1999-2019 |

| Amarin | 1999-2019 |

| Auxilium | 2002-2014 |

| Bausch | 1999-2019 |

| Baxalta | 2012-2015 |

| Bracco | 2003-2015 |

| Dendreon | 1999-2014 |

| Dompe | 2004-2018 |

| Elan | 1999-2011 |

| Emergent | 2004-2019 |

| Endo | 1999-2019 |

| Forest | 1999-2013 |

| Grifols | 2000-2019 |

| Horizon | 2008-2019 |

| Incyte | 1999-2019 |

| Indivior | 2011-2019 |

| Ionis | 1999-2019 |

| Ipsen | 2002-2019 |

| Jazz | 2015-2019 |

| King | 1999-2009 |

| Leo | 2008-2018 |

| Lundbeck | 1999-2019 |

| Mallinckrodt | 2011-2019 |

| Meda | 1999-2015 |

| Medicines Co | 1999-2018 |

| Merz | 2015-2019 |

| Millenium | 1999-2007 |

| Nu Skin | 1999-2019 |

| Nycomed | 2002-2010 |

| Servier | 2004-2019 |

| Shire | 2004-2018 |

| Talecris | 2005-2010 |

| UCB | 1999-2019 |

| Vertex | 1999-2019 |

E2. Major biopharma firms in analysis data |

Data period | ROA |

| Abbott | 1999-2012 | y |

| AbbVie | 2013-2019 | y |

| Alexion | 1999-2019 | y |

| Amgen | 1999-2019 | y |

| Astellas | 2005-2019 | y |

| AstraZeneca | 1999-2019 | y |

| Aventis | 1999-2003 | |

| Bayer (pharma) | 1999-2019 | |

| Beecham | 1999 | |

| Biogen (Biogen Idec) | 1999-2019 | y |

| Biogen (pre Idec) | 1999-2002 | |

| BioMarin | 1999-2019 | y |

| Boehringer Ingelheim | 1999-2019 | y |

| Bristo Myers Squibb | 1999-2019 | y |

| Celgene | 1999-2019 | y |

| Chiron | 1999-2005 | |

| Chugai | 1999-2019 | y |

| Daichi | 1999-2004 | |

| Daichi Sankyo | 2005-2019 | y |

| Eisai | 1999-2019 | y |

| Eli Lilly | 1999-2019 | y |

| Fujisawa | 1999-2004 | |

| Genentech | 1999-2008 | |

| Genzyme | 1999-2010 | |

| Gilead | 1999-2019 | y |

| GSK | 1999-2019 | y |

| HGS | 1999-2012 | y |

| J&J (Janssen pharma) | 1999-2019 | y |

| Kyowa Hakko Kirin | 1999-2019 | y |

| MedImmune | 1999-2006 | |

| Merck | 1999-2019 | y |

| Merck AG | 1999-2019 | y |

| Mitusbishi Tanabe | 1999-2019 | y |

| Novartis | 1999-2019 | y |

| Novo Nordisk | 1999-2019 | y |

| Otsuka | 1999-2019 | |

| Pfizer | 1999-2019 | y |

| Pharmacia | 1999-2002 | |

| Regeneron | 2004-2019 | y |

| Roche | 1999-2019 | y |

| Sankyo | 1999-2004 | |

| Sanofi | 1999-2019 | y |

| Schering AG | 1999-2005 | |

| Schering Plough | 1999-2007 | |

| Seattle Genetics | 1999-2019 | y |

| Serono | 1999-2005 | |

| Shionogi | 1999-2019 | y |

| Sumitomo Dainippon | 1999-2019 | y |

| Taisho | 1999-2019 | y |

| Takeda | 1999-2019 | y |

| United Therapeutics | 1999-2019 | y |

| Upjohn | 1999 | |

| Warner Lambert | 1999 | |

| Wyeth | 1999-2007 | |

| Yamanouchi | 1999-2004 |

Appendix 2: Notable PBMs – Entries and Exits

| Examples of PBM entry and exit | Parent type | PBM Started | PBM exited | Entry mode | Exit mode |

| Anthem/IngenioRx | Insurer | 2019 | operating | Internal | |

| Diplomat Pharmacy Services | Pharmacy | 2017 | 2020 | Bought LDI & National | Sold to OptumRx |

| CerpassRx | PBM | 2015 | operating | Internal | |

| Rite Aid / EnvisionRX | Pharmacy | 2015 | operating | Bought EnvisionRx | |

| Magellan Rx | HC services | 2010 | operating | Bought First Health; later bought Partners Rx | |

| RxAdvance | PBM | 2013 | operating | Internal | |

| Integrated Prescription Management (IPM) | PBM | 2009 | operating | Internal | |

| Catamaran / SXC | PBM | 2008 | 2014 | Internal | Sold to UnitedHealth |

| Navitus Health (Dean Health / SSM Healthcare) | HC services | 2008 | operating | Bought Navitus Health | |

| Humana | Insurer | 2006 | operating | Internal | |

| Centene / US Script / Envolve | Insurer | 2006 | operating | Bought US Script; later bought Envolve (2015) | |

| Abarca Health LLC (FL/PR) | PBM | 2005 | operating | Internal | |

| UnitedHealth / OptumRx | Insurer | 2005 | operating | Internal; later bought AmeriChoice & Prescription Services | |

| First Health / Coventry | HC services | 2005 | 2009 | Bought First Health Group | Sold to Magellan |

| Medco3: Medco Inc. (post Merck) | PBM | 2003 | 2012 | Spun by Merck | Sold to Express Scripts |

| Envolve Health | HC services | 2002 | 2015 | Internal | Sold to Centene |

| Navitus Health Solutions | PBM | 2002 | 2007 | Internal | Sold to Dean Health / SSM |

| Aetna | Insurer | ~2002 | 2019 | Internal | Sold to CVS |

| Envision RX | PBM | 2001 | 2014 | Internal | Sold to TPG (2013) & Rite Aid (2014) |

| PCS5: Advance PCS / Advance Paradigm (post Rite Aid) | HC services | 2001 | 2003 | Bought from Rite Aid | Sold to Caremark Rx / MedPartners |

| Partners Rx | PBM | 2001 | 2013 | Internal | Sold to Magellan |

| Anthem Wellpoint | Insurer | ~2000 | 2009 | Internal; later bought Wellpoint (2004) | Contracted PBM to Express Scripts (2009) |

| PCS4: Rite Aid (post Lilly) | Pharmacy | 1999 | 2000 | Bought from Lilly | Sold to Advance Paradigm |

| Perform Rx | PBM | 1999 | operating | Internal | |

| ProAct (KPH Healthcare, Kinney Drugs) | Pharmacy | 1999 | operating | Internal | |

| US Script | PBM | 1999 | 2005 | internal | Sold to Centene |

| Catalyst Health Solutions | HC services | 1999 | 2012 | Internal | Sold to SXC/Catamaran |

| Regence Rx / Cambia Health Solutions | HC services | 1999 | operating | Internal | |

| Prime (BCBS) | PBM | 1998 | operating | Internal | |

| First Health Group / Health Compare | HC services | 1998 | 2004 | Bought First Health Services | Sold to Coventry |

| Accredo Health / Nova Holdings | HC services | 1996 | 2005 | Internal | Sold to Medco |

| CM5: CVS Caremark | Pharmacy | 1996 | operating | Internal; later bought Caremark (2006) & others | |

| CM4: Caremark Rx / MedPartners / AdvancePCS | HC services | 1996 | 2006 | Bought Caremark | Sold to CVS |

| PCS3: Lilly (post McKesson) | Life science | 1995 | 1998 | Bought from McKesson | Sold to Rite Aid |

| Pharmacy Gold / Aware Integrated (BCBS MN) | Insurer | 1994 | operating | Internal | |

| Cigna | Insurer | ~1994 | operating | Internal; later bought Express Scripts (2018) | |

| Alta Health Strategies / First Financial Management | HC services | 1992 | operating | Bought Alta | |

| Medco2: Merck Medco | Life science | 1994 | 2002 | Bought by Merck | Spun by Merck |

| DPS2: SKB (post United) | Life science | 1994 | 1998 | Bought from United | Sold to Express Scripts |

| National Pharmaceutical Services | PBM | 1993 | 2017 | Internal? | Sold to Diplomat |

| Prescription Solutions (PacifiCare) | Insurer | 1993 | 2005 | Internal | Sold to United (became OptumRx) |

| Kroger Prescription Plans | Pharmacy | 1993 | operating | Internal | |

| WellDyneRx / RxWest | PBM | 1992 | operating | Internal | |

| MaxorPlus (Maxor) | HC services | 1991 | operating | Internal | |

| CM3: Caremark International | PBM | 1991 | 1995 | Spun by Baxter | Sold to MedPartners |

| Health Net of California (Foundation Health) | HC services | 1990 | 2016 | Internal? | Sold to Centene |

| Wellpoint | Insurer | 1990s | 2004 | Internal | Sold to Anthem |

| First Health Services | HC services | ~1990s | 1997 | Internal | Sold to Health Compare (took First Health Group name) |

| Integrated Pharmaceutical Services (Foundation Health) | HC services | ~1990s | 1999 | Internal | Sold to Advance PCS |

| LDI Integrated Pharmacy Services | HC services | ~1990s | 2017 | Internal? | Sold to Diplomat |

| EcKerd Health Services / TDI | Pharmacy | ~1990s | 2004 | Internal | Sold to CVS |

| CM2: Caremark / Baxter | Life science | 1988 | 1990 | Bought Caremark | Spun by Baxter |

| MedImpact Healthcare Systems | PBM | 1989 | operating | Internal | |

| Value Rx | PBM | 1987 | 1998 | Internal | Sold to Express Scripts |

| Serve You Custom Prescription Management | PBM | 1987 | operating | Internal | |

| Express Scripts | PBM | 1986 | 2018 | Internal | Sold to Cigna |

| Alta Health Strategies (UT) | HC services | ~1986 | 1992 | Internal | Sold to First Financial Management |

| Medco1: Medco Containment Services (pre Merck) | PBM | 1983 | 1993 | Internal | Sold to Merck |

| Argus / DST / SS&C Technologies | HC services | 1983 | operating | Internal | |

| Omnicare | HC services | 1981 | 2015 | Internal | Sold to CVS |

| CM1: Caremark / Home Healthcare of America | PBM | 1979 | 1987 | Internal | Sold to Baxter |

| DPS1: United Healthcare | Insurer | 1976 | 1993 | Internal | Sold to SmithKlineBeecham |

| PCS2: McKesson | Wholesale | 1972 | 1994 | Bought PCS | Sold to Lilly |

| PCS1 | PBM | 1969 | 1971 | Internal | Sold to McKesson |

Note: Dates and modes are based on public sources, which sometimes conflict; the tables report best estimates.