Mark V. Pauly, Koushal Rao and David Futoran, The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania

Contact: pauly@wharton.upenn.edu

Abstract

What is the message? If medical care consumers are to make better choices among competing sellers of well-defined services, they will, we are told, need more transparency on the price they will pay, on quality, and on ease of access. Some states have established programs to mandate such information, and the federal government has recently required hospitals to disclose all prices charged and received. This paper explores the novel issue of the power of and interest by sellers themselves in furnishing information on price when they have decided to charge low prices in their local market—along with information on quality or access. We provide a conceptual discussion of why such information may or may not be supplied.

What is the evidence? We illustrate actual seller behavior by extracting data from provider websites in New Hampshire and Maine for a number of common procedures. We provide evidence that, as might be expected, those sellers charging lower prices in their markets are more likely to mention price or some proxy for it in their website, while higher priced sellers are silent about price but mention quality or convenience. However, we find that many low-priced sellers do not draw potential buyers’ attention to this fact, and consider some possible reasons for this apparent paradox.

Timeline: Submitted July 27, 2020; accepted after review August 3, 2020

Cite as: Mark Pauly, Koushal Rao, David Futoran. 2021. Light Under A Bushel: Medical Price Transparency Regulation And Low Priced Seller Behavior. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI.org), Volume 6, Issue 1, Winter 2021.

How Can We Achieve Price Transparency?

Hospitals and healthcare providers are caught in the crossfire between two groups that want to use very different methods to reduce spending on their services. Some critics want to move public policy toward stricter regulation of prices or reimbursements received, having them controlled or set by a single payer. Others envision a more aggressive competitive market in which consumer-patients searching for better deals put pressure on all sellers to keep down what consumers have to pay. The Trump administration recently won court approval for a regulation that requires hospital disclosure of prices received from all buyers, taking the view that consumers, especially those with higher deductibles in their insurance plans, can benefit from transparency of prices different buyers charged for medical services and that those prices should neither be obscured before services are rendered nor kept secret afterwards. [1]

Markets for medical services do not work the same as other potentially competitive markets because of the presence of health insurance, whose form can strongly affect the potential gain to consumers from knowing about lower priced sellers. Transparency is not of great value for heavily insured services, ones whose price exceeds the typical deductible, or ones for which there is little opportunity for patient choice. However, though it still only covers a minority of the population, the striking growth in high-deductible health insurance has generated interest in consumer price information for commodity-type-services priced high but below the deductible.

Variation in list prices for such medical services (where patient severity or other characteristics should have minimal effects on cost), such as MRI scans or routine colonoscopies appears to be large in most markets, and variation across payers transacting with a given provider are common. This evidence on price variation has led to proposals and legislation designed to bring about greater price transparency for these medical services, in order to assist consumers who could save by choosing lower priced sellers. In this policy discussion the presence of price variation and the absence of good information about prices have been taken as given, thus motivating the need for public regulation of transparency and public support for dissemination of that information.

In this paper we argue that there is another vehicle for price transparency which has been ignored—the firms that charge low prices may have an incentive themselves to bring that fact to the attention of consumer buyers. Sellers need not be viewed as passive price setters, some greedy and others neglectful of profit maximization, who just somehow generate the large variation in prices. Instead, some of those firms who choose to set below average prices may benefit from having buyers know about the bargains they offer.

Some Firms That Charge Low Prices Have Incentives To Publicize That Fact

We first describe the economic models in which some — but by no means all — firms might choose to provide information on their below-average prices. We then use data from states that have been most aggressive in the push for price transparency to show that in practice firms with prices at the lower end of the distribution of prices in a market do not just wait for buyers aided by government to arrive. Instead many of them take an active role. However, not all sellers make their prices transparent, and not even all low priced seller push out information about that fact. Sometimes there are good theoretical reasons for them to conceal, but sometimes government assistance might help.

It is important to add that price information alone is not sufficient for good consumer decisions; there also needs to be adequate information about the quality and amenities supplied by different providers, to be compared to prices. So, multidimensional transparency is a reasonable policy goal.

There is, of course, an insurer model alternative to the consumer directed high-deductible plan in which the consumer’s insurer, not the individual, does the searching and bargaining over price and quality; this is still the more common arrangement in low-deductible plans and even in some high-deductible plans where insurers make their networks and discounted prices available to insureds who are under the deductible. There clearly is growth in plans where patients are supposed to take responsibility for price shopping and there does seem to be bipartisan sentiment for, at a minimum, disclosure of what the consumer will be expected to pay.

Current Policy Goals: Demands For Price Transparency

Current policy discussions by the Trump administration and industry critics have argued that more price transparency is needed. The Administration has proposed rules to use Medicare data to improve transparency [2]. The president claims this is important – “this is bigger than anything we have ever done in this particular realm.” [3]. The ultimate goal appears to be that of letting each consumer know where the use of lower priced sellers can lead to lower out of pocket payments, given the deductibles and coinsurance in each consumer’s policy.

However, because of the nature of insurance coverage and the emotional issues that often surround decisions about medical care, especially that for immediate health needs, so far it appears that many consumers in high deductible plans may not themselves choose to seek or shop for lower prices for such services [4]. Recent research using data from individual employers and plans suggests that individual consumers do not regularly search in their local markets to find lower priced sellers [5]. Still, it seems a matter of simple economics that somehow making it both important and easy for consumers to compare prices for standard services could increase effective competition that might lower spending on those services [6].

Why Transparency Policy Is Not Always Best

Despite the current demands for price transparency, there are two important issues here that have not been well considered. First, as George Stigler noted in his classic work [7], the absence of a perfectly competitive market structure and the presence of oligopolistic interaction between sellers may mean that better information might lead average prices actually paid to increase, as dominant firms more easily detect and punish price cutting by smaller rivals. We have treated the possibilities and the circumstances in which this might happen elsewhere [8]. This turns out to be a complex question with few a priori answers, with some empirical support for other industries in other countries (e.g, cement in Denmark) but no bulletproof evidence for the US insured medical care markets.

The second issue is much simpler but even more neglected in the discussion. If at least some semblance of competition is at work, there should be another source of information to consumers about prices: the sellers themselves [9]. This is because there is little financial advantage to those firms charging lower prices than others unless their prices attract a larger volume of business than would higher prices – and enough additional volume to offset the lower prices.

To outline the obvious, here is how that would work. Suppose there are five firms in a community selling MRI scans of the back. Seller A charges the lowest price, though we might wonder why. But if that seller seeks profits or net income, or even just a greater role in providing services to the community, it should be eager to inform buyers of its price and that its list price is the lowest in town – information that it could collect relatively easily. That should lead the second-lowest priced seller (seller B) to inform buyers that it is less costly than the other three sellers C, D, and E. This process will continue until only seller E is silent about its price, but consumers will know that silence must mean that it is the most expensive facility in town.

In short, a number of incentives should prompt sellers to furnish price information, with no necessary need for laws or grants or external agencies to compile buyers’ guides – though having public sector help in disclosing price would still help. Nor would rules compelling disclosure of lower prices be needed. In the words of one commentator, “One might think that providers who can deliver a comprehensive set of services at a (low) negotiated price would relish the notion of having that price fully disclosed.”[10]. In economics, the sellers should not only relish someone’s help in publishing low prices, they should actually publicize the low prices themselves. So do actual medical markets work the way economics suggests?

Economic Models of Price Dispersion

Logic

In perfectly competitive markets, economic theory proves that the Law of One Price will hold: all firms and all buyers will pay the same price which just generates normal profits. If there is a reasonably large number of sellers, in order to get a model that allows for dispersed prices, one needs to assume some impediment to buyer search, either “search costs” or “switching costs.” Such models have been proposed by Steven Salop and co-authors. [11.12].

Even then, if buyers can also provide information, as in the spirit of our introductory remarks, no equilibrium may exist or no search may exist [9]. Depending on the kinds of searching and the methods of searching, there can also be models where dispersed prices emerge but may or may not generate an equilibrium, as opposed to permanent churning [13]. Generally speaking, as long as at least some buyers only sample one seller while others sample more than one, an equilibrium with dispersed prices is possible.

These models all build on the early work of Stigler (1961) [7] on search costs, primarily on his theory but also on his empirical observation that price dispersion is smaller for consumer big ticket items where search provides more benefit. Stigler was concerned about oligopoly behavior (e.g., few sellers because of barriers to entry like small market size), noting that better information to competitors about rivals’ prices in such a situation may paradoxically lead to higher prices if it threatens secret discounts offered by some sellers, a prediction for which there is some theoretical evidence in markets for industrial products like concrete [14,15].

In the application to medical services, the key assumption that some buyers search more than others seems eminently plausible. Among other reasons, if some buyers will pay out of pocket, or a larger proportion out of pocket, while others have more complete insurance coverage, there should be differences in search behavior.

The purpose of government efforts to improve price transparency is to help the high-deductible subpopulation, although it has proven challenging to do so. The reason is that data on payments to sellers by insurers often bear little relationship to what a consumer who has to pay will be charged. List prices that would be paid by a well-off but uninsured person almost always exceed insurer payments, while lower income uninsured may get discounts, and some of those with high deductible plans have access to insurer negotiated prices while others do not. [16,17]. In addition, different insurers may pay quite different amounts to the same seller for the same service. Discovering that someone else (or someone else’s insurer) paid less than you are being charged by a healthcare provider may make for irritation and a good argument but is unlikely to move the provider to change behavior if you have fewer options or lower bargaining skills than the bargain hunter. You are not going to be able to pay the Medicaid price.

These reasons may account for the general failure to find large positive impacts from state programs for price transparency, at least so far. [18, 19]. To illustrate these points further, we now present an empirical model of the relationship between prices firms set and actions firms take, and illustrate it with the oldest and most comprehensive publicly mandated price data on medical procedures, that from New Hampshire and Maine.

Conceptual Model

In order to develop a model with price dispersion in equilibrium, there must be some impediment to buyer ability to know about and patronize different sellers. Otherwise all buyers will move to the lowest priced sellers and price will be uniform. As noted above, one common assumption therefore is that buyers differ in terms of search costs or search strategies—some may choose or sample only one seller while others obtain information and consider using different sellers. A firm that sets a high price will therefore tend to sell to those who do little search, and will have low volume, while a firm with lower prices will attract more buyers among those who search.

Of course, a buyer searching – or even just ending up at – only one firm might by chance hit the lowest price seller, but the average price paid by low searchers will be higher than that paid by high searchers. However, profits per firm may be equal across firms with different prices, under plausible assumptions about economies of scale, as high-priced sellers make more profit per unit but sell fewer units than low-priced sellers. If profits are the same regardless of price chosen, within limits, there will be no incentive for a firm to change pricing to increase profits.

In the study to follow we needed to find settings in which price information was available to us as researchers. New Hampshire and Maine are two of the three states with the longest history and most explicit government efforts to create price transparency [20]. The other state (Massachusetts) has an array of other price regulation devices that may confound efforts to identify the role of price information alone, while the many states with public data files on hospitals generally do not make that information easy for consumers to use. If anything is going to happen, it should happen in New Hampshire and Maine.

For those buyers using state information, search costs are reduced, and so any seller provided with information will have an effect only if it calls attention to or adds to the information buyers can use. In the spirit of Stigler’s original work, making price information available to buyers also makes it available to other sellers and thus increases the ability of dominant firms in an oligopoly to detect and punish low-priced sellers, thus driving them out of business or getting them to fall in line with a higher price.

Hence it is an empirical question whether low-priced firms will find it advantageous to advertise their price; are they in an oligopoly game where almost every buyer gets a special confidential low price, or are they in a more competitive setting where large firms (or all other firms) do not automatically respond to individual firm price reductions? However, it will always be the case that it will be disadvantageous for high-priced firms to volunteer that information, unless they have some quality or convenience offset they want to publicize.

So we would expect seller efforts to publicize prices when their prices are low to characterize some though not necessarily all low-priced firms. High-priced firms will continue to have an incentive, perhaps even a stronger one, to publicize higher quality or convenience if they can furnish high enough above-average values to justify their prices. High-priced firms with mediocre quality or access will stay quiet in hopes that some foolish low searching buyers will happen their way.

Illustrating the Theory: Motivation and Design

Therefore, we look at information on what efforts sellers make to disclose price, using data on prices and disclosures from New Hampshire and Maine. We test the hypothesis that low-priced sellers provide information on their pricing behavior. Both states have programs in which a state agency collects seller- and service-specific price information and makes it available to the public. The New Hampshire program was graded as the best program in the country in a report card released by the Catalyst for Payment Reform and Health Incentives Improvements Institute in 2015 [21]. The New Hampshire state pricing website lists prices paid by different payers, including self pay or “uninsured.” The Maine site lists only insurer prices.

To explore how sellers view the program and how they set and publicize prices, we reviewed seller websites to see whether information to suggest lower prices was present or not. We made follow up phone calls if the information was unclear. This review was conducted in May and June 2016, and was updated in June 2017. This information allows us to see whether sellers themselves call attention to their pricing and which kinds do so. We also see whether higher quality sellers bring those facts to consumers’ attention, potentially as a countervailing influence if their price is high. We look at what sellers, charging higher prices, say about convenience and wait time, since time cost can offset money cost.

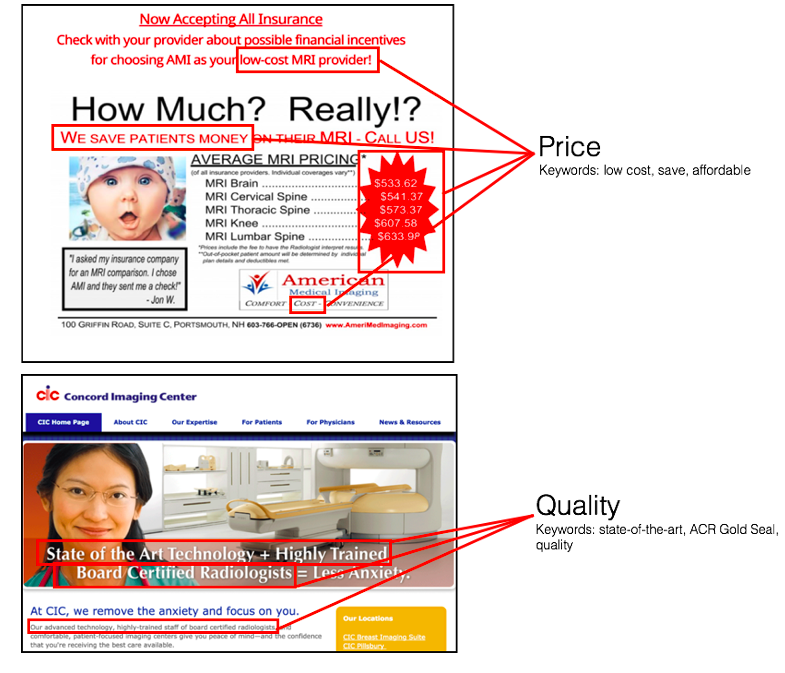

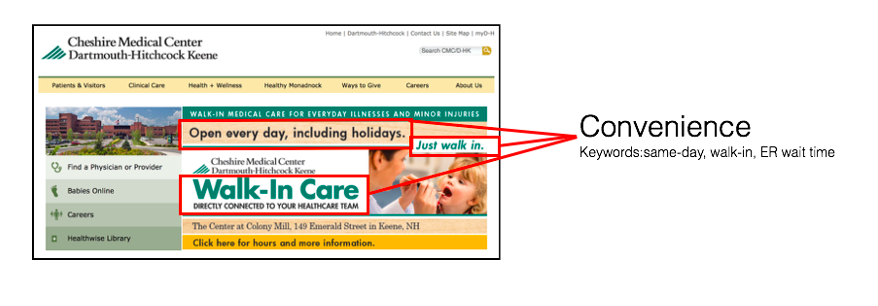

After a test exercise using older posts, a trained reader tabulated mentions of price, quality, or access on each site, blind to the relative price of other sellers. It was not difficult to identify specific mentions of price or affordability, as indicated in Exhibit A.

Exhibit A

The key words used to identify price were “low cost,” “save,” and “affordable.” Those for quality included “state-of-the-art,” “ACR Gold Seal,” and “quality.” Access was flagged if “same-day,” “walk-in, or “ER wait time” were mentioned. A given site could mention all or some of these characteristics.

The key words used to identify price were “low cost,” “save,” and “affordable.” Those for quality included “state-of-the-art,” “ACR Gold Seal,” and “quality.” Access was flagged if “same-day,” “walk-in, or “ER wait time” were mentioned. A given site could mention all or some of these characteristics.

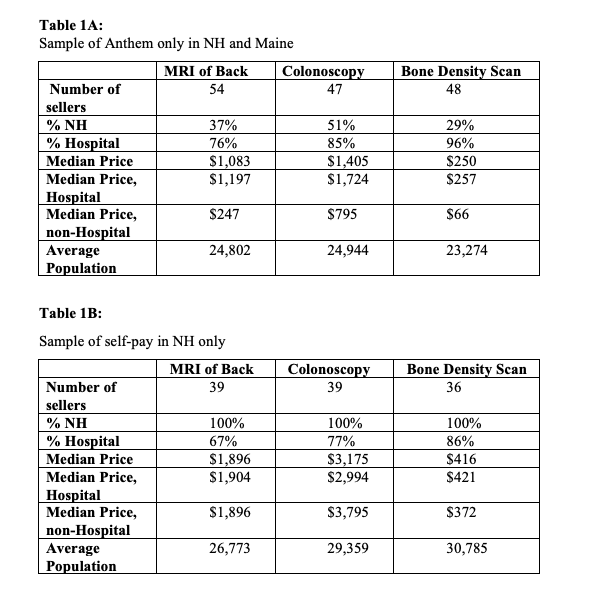

For Maine data, only one price, that facing insurers, was published. For New Hampshire, different prices for the two largest insurers (Anthem and Harvard Pilgrim) along with the list price for those reporting self pay or no insurance coverage for a particular service. We analyzed the New Hampshire data and found high correlation between the three price schedules. We therefore used only Anthem prices for the main analysis. Unfortunately, the New Hampshire sample was too small to allow meaningful analysis of differences between insurer paid prices and prices for the self-paying public. Tables 1A and 1B provide descriptive information on the numbers, types, locations, and median prices of sellers in our analysis sample.

Results

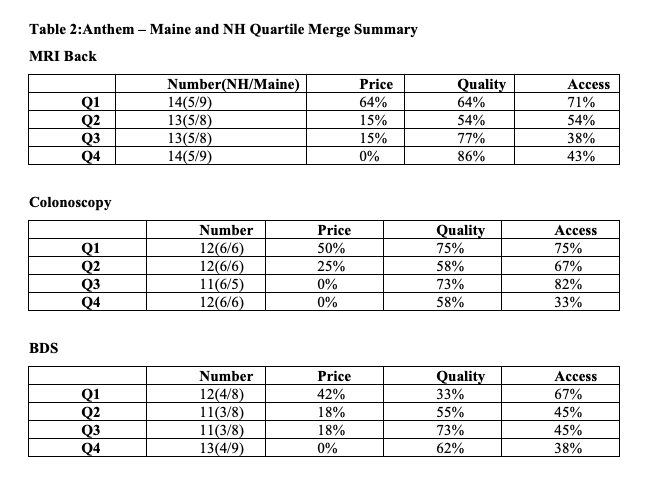

The main purpose of this study is to show the relationship between price charged and the type of information provided. As can be seen in Table 2, provision of price information was almost strictly limited to non-hospital organizations in the bottom quartile or bottom half of the price distribution for all three services.

This difference in the proportion of sellers advertising price as a function of the quartile of price is statistically significant versus the null hypothesis of equal proportions in each price quartile for all three procedures (at the 0.001 level for MRI, and at the 0.05 level for the other two procedures). It also shows that the frequency of advertising price was zero in the highest quartiles but most common in the lowest priced quartile.

However, even among these low-priced sellers, almost none of which were hospital based, many did not advertise price. Many sellers who chose to set prices much lower than average did not mention that fact as a main way they communicate with potential buyers, although more of them did so than their higher-pricing counterparts. So, a puzzle remains, one we will discuss but not resolve further below.

For the other dimensions of care that might matter to consumers – quality and convenience – mention was more common on websites than was mention of price, and mention of either dimension was either unrelated to price or only weakly (and directly) related. Higher priced sellers sometimes were more likely to tout quality. Information on either of these dimension, in contrast to price, was usually not comparative—e.g., “our goal is to provide high quality and convenient care” — but without information on ranking or performance relative to competitors.

Discussion

The most striking finding with this modest data, though the best available, here is that, consistent with the assumptions of Peter Diamond’s model: sellers do not just passively set prices. Instead, if they set low prices they are more likely to publicize that fact, explicitly or subtly, in the information they provide on websites. This relationship is strongest for MRI imaging, consistent with the high volume of demand for that test and its relatively high fixed cost and price, but it also is apparent for the other services we examined. There is also a strong hint that high-priced firms turn to publicizing their quality, whatever it is, to offset their high prices. Some mention greater convenience or say nothing at all on their website other than characteristics of the entity and its address and phone number.

Why do some low-priced sellers not mention that fact on their websites? We do find strong evidence that free-standing sellers mention price more often than low-priced hospitals, who are less common. There is some suggestion that price mention is more likely in more populous markets where there are presumably more alternatives.

Perhaps some organizations do not have net revenue maximization or fiscal growth as a goal; they just want to offer low-priced care in their communities even though they could charge more and sell about the same amount. Others may not be so attentive to fiscal matters as long as they are breaking even. We cannot determine these motives from this data, obviously, but they deserve to be explored with more targeted inquiries.

Other Issues

It is also possible that some insurance companies may play a role in why many firms do not advertise their low prices. Some insurance companies have adjusted their benefit-design plans in a way that uses the newly available information about the low-priced firms to incentivize their patients to see the low-priced providers. Accordingly, providers may care more about making their price information available to insurance companies rather than to patients via advertisements.

Perhaps, as well, low-priced firms feared customers would judge quality by price, though we found little evidence that low-priced firms offered reassurance on quality to any greater extent than other firms. If that hypothesis were true, however, it would pose the further question of why then the firm charged a low price if doing so would only deliver the wrong message to buyers. Indeed, the most serious gap in our understanding of how price transparency works is the absence of an explanation of why there are low-priced sellers in the initial case.

Another possible explanation for low-priced sellers is that they may not have a choice. Large hospitals that service tens of thousands of patients have a strong negotiating standpoint to demand higher payments. Smaller independent facilities may lack that same negotiating power and be forced to accept lower payments from insurance companies as a result. It was observed, in fact, that although the prices across no insurance, Anthem insurance, and Harvard Pilgrim insurance were correlated, the prices for uninsured individuals were invariably higher than those for insured individuals.

Still, there was significant variation across firms among the prices offered to uninsured individuals, which returns us to the question of why the low-priced sellers exist in the market. Perhaps, however, some low priced sellers decided to specialize in attracting Anthem or Harvard Pilgrim customers. While some firms have emerged to attempt to help consumers seek better buys (e.g. Castlight, https://www.castlighthealth.com/), breaking the code of silence that seems to affect many sellers may be the key to making price transparency matter.

Policy Issues

As noted earlier, there has been bipartisan support for regulations that require all hospitals or other sellers of medical services to be fully transparent about the prices they charge and receive from different buyers. Some sellers who would have wanted buyers to know anyway about their lower prices, or higher value for a given price, may benefit from such actions. However, others who have pursued a strategy of secret price concessions to foil large oligopolistic competitors may lose from such a one-size process.

Perhaps it is reasonable to consider an alternative policy, one that begins with a template or model of full price disclosure set up by government and then permits different sellers to decide voluntarily whether they want to participate. That is, sellers can choose to be certified as low priced but they are not required to disclose low prices. In addition, public policy would provide clear and easy to access information on the prices charged by those sellers who participate, as well as explicit identification of those firms that have decided to keep their prices hidden.

There are complex legal issues that would have to be addressed if such a policy were to be formulated for concrete application. However, we believe that this kind of regulation/deregulation might generate less opposition and more realized consumer benefits than other approaches. Of course, any steps that could be taken to reduce oligopoly power — access to larger numbers of sellers, limitations on mergers and acquisitions — would also be desirable. Sometimes it may be desirable to permit some sellers to keep present and especially future bargains confidential. Nonetheless, as long as those consumers who must function as individual buyers can work around such limits by using other sellers, the potential of hidden discounts to offer better deals to those whose insurers shop for them may be of value.

Looking Forward

The conclusion is that the pattern of firm-provided information in two states is broadly consistent with what one would expect if profit-seeking firms were competing for business. However, the pattern is by no means precise and universal. Price disclosure by all such firms so far does not seem to be something that sellers can be shown to relish; a sizeable fraction of firms do not communicate their low prices.

It is plausible to assume that seller provision of information about prices, quality, and convenience does help consumers looking for low prices and high value, especially those with high- deductible health plans who are not assisted by their insurers. The generally small or zero effects thus far of state efforts, like those of these two states, to improve price transparency suggests that federal regulation requiring disclosure may not be safe and effective in all settings.

Since policy efforts to date have been primarily directed at consumers, it might be time to broaden the focus to include sellers. If an imaging center was willing to go with the slogan “fifteen minutes can save you 15% on the cost of your MRI scan,” there might be a disruptive change in the market at last.

References

- Kliff, S., Sanger-Katz, M. Hospitals sued to keep prices secret. They lost. The New York Times, 2020 June 23. Retrieved July 12, 2020 from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/upshot/hospitals-lost-price-transparency-lawsuit.html

- Commins, J CMS unveils sweeping proposed mandates on hospital pricing transparency. Health Leaders. 2019 July 29. https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/finance/cms-unveils-sweeping-proposed-mandates-hospital-pricing-transparency. Accessed November 6, 2019

- CBS News. Trump signs executive order to make health costs more transparent. 2019 June 25. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-signing-executive-order-health-care-costs-2019-06-24-live-updates/. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- Mehrotra, A, Chernew, ME , Sinaiko, AD. Promise and reality of price transparency. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018; 378(14): 1348-1354.

- Brot-Goldberg, Z, Chandra, A, Handel, BR, Kolstad, J. What does a deductible do? The impact of cost-sharing on health care prices, quantities, and spending dynamics. NBER Working Paper 21632; 2015. http://www.nber.org/papers/w21632. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- Sinaiko, AD, Kakani, P, Rosenthal, MB. Marketwide price transparency suggests significant opportunities for value-based purchasing. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2019; 38(9). https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05315. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- Stigler, George J. The economics of information. Journal of Political Economy. 1961; 69(3): 213-225.

- Pauly, MV, Burns, LR. When is medical care price transparency a good thing (and when isn’t it)? Advances in Health Care Management. In press.

- Diamond , P. A model of price adjustment. Journal of Economic Theory. 1971; 3(2): 156-168.

- De Brantes, F. HCI3 Update from the field: The cost of hope. Newtown, CT: Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute; 2013. Available at: http://www.hci3.org/content/hci3-update-field-cost-hope. Accessed 2013.

- Salop, S, Stiglitz, J. Bargains and ripoffs: A model of monopolistically competitive price dispersion. Review of Economic Studies. 1977; 44(3): 493-510.

- Perloff, J, Salop, SC. Equilibrium with product differentiation. Review of Economic Studies. 1985; 52(1): 107-120.

- Burdett, K, Judd, KL. Equilibrium price dispersion. Econometrica 1983;51(4).

- Albaek, S, Møllgaard, P, Overgaard, PV. Government assisted oligopoly coordination? A concrete case. Journal of Law and Economics. 1997; 45 (December): 429-443.

- Austin, DA, Gravelle, JG. Does price transparency improve market efficiency? Implications of empirical evidence in other markets or the health sector.” Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2007. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/secrecy/RL34101.pdf. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- Melnick, GA, Fonkych, K. Hospital pricing and the uninsured. Do the uninsured pay higher prices? Health Affairs. (Millwood.) 2008; 27(1). https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w116. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- White, C, Whaley, C. Prices paid to hospitals by private health plans are high relative to medicare and vary widely. Santa Monica, California: The Rand Corporation; 2019. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3033.html. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- Gustafsson, L, Bishop, S. Hospital price transparency: Making it useful for patients. New York: The Commonwealth Fund. February 12, 2019. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/hospital-price-transparency-making-it-useful-patients. Accessed November 6, 2019.

- Tu, H, Lauer, J. Impact of health care transparency on price variation: The new hampshire experience. Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2009.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Public reporting of cost measures in health. Washington, D.C.: AHRQ; 2015. Retrieved July 11, 2020 from https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/public-reporting-cost-measures/technical-brief

- Delbanco, SF. The payment reform landscape: States show little progress in past year. Health Affairs. (Millwood) 2015 July 9. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150709.049227/full/. Accessed November 6, 2019.