Barak Richman, Katherine T. Bartlett Professor of Law and Professor of Business Administration, Duke University

Contact: richman@law.duke.edu

Abstract

What is the message: Efforts to make healthcare markets work efficiently are laudable but often suffer from ideological blinders, a failure to assess the nuances of empirical research, and an inadequate approach to the morality of the marketplace. Critics of market approaches often exhibit the same shortcomings.

What is the evidence: This article assesses the empirical literature on the successes of market transparency and healthcare consumerism, offers some tempered enthusiasm for certain market-based efforts, and identifies the underemphasized value of agency as a guidepost for healthcare reform.

Timeline: April 21, 2022; accepted after review: April 22, 2022.

Cite as: Barak Richman. 2022. Shopping for Healthcare: Can We Be Good Consumers? Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.HMPI.org), Volume 7, Issue 2.

This article is adapted from the 2019 Nordenberg Lecture at the University of Pittsburgh. I thank Sydney Engle and Jennifer Behrens for outstanding research assistance, and I thank Alan Meisel, Mark Nordenberg, the University of Pittsburgh Health Law Faculty for their invitation and hospitality during that visit.

I additionally want to recognize Mark Nordenberg and the late Thomas Detre for creating the Nordenberg Lecture. Their collaboration offers a model that this article aspires to follow: providing good healthcare requires a consultation with many values, and improving the health sector requires contributions from multiple disciplines and perspectives. The collaboration between Thomas Detre and Mark Nordenberg offers a model for the rest of the academic community. Thomas Detre was the chancellor of the health system. Mark Nordenberg was the chancellor of the university. Dr. Detre was a refugee from Budapest and a survivor of the Holocaust from Budapest. Professor Nordenberg grew up in the upper Midwest and spent his entire career in the heartland of America. They came to their jobs and to their careers with vastly different outlooks and life histories, but they collaborated to bring the resources of the university together to improve healthcare for their communities and for America. That is a model for moving forward.

Introduction: A Picture Is Worth 1,000 Words

On June 27, 2019, President Trump issued Executive Order #13877, “Improving Price and Quality Transparency in American Healthcare To Put Patients First,” to require disclosure in one of the least transparent and most important parts of our healthcare system: what insurers and payers are paying for healthcare services.[1] Seema Verma, then the administrator of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said that the Executive Order would be a first step toward consumerism.[2] If everyone knows what the prices are, then everyone can act as intelligent and effective consumers.

To show its support, the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) distributed a T-shirt with the truism: “American Health Care Danish Cement.”[3]

To show its support, the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) distributed a T-shirt with the truism: “American Health Care Danish Cement.”[3]

The T-shirt, not the truism, is worth the proverbial thousand words. The committee, like the Executive Order, was operating under the common presumption that markets can function properly only when consumers can compare prices, and thus healthcare markets can work when prices for physician and hospital services are disclosed. But then some Danish researchers threw a wrench into that neat theory. Government-Assisted Oligopoly Coordination? A Concrete Case revealed after the Danish government publicly published prices for concrete, concrete prices increased by 15% to 20%.[4] Though the article cannot determine whether prices went up because of the price disclosures, its findings certainly challenge the syllogism that more information leads to better competition and lower prices.

Source: Margot Sanger Katz (@sangerkatz). August 20, 2019. https://twitter.com/sangerkatz/status/1163830456963555335

The T-shirt offers two lessons. First, the Senate HELP Committee’s shirt reveals more than just an underlying debate about the effect of price transparency on healthcare prices. It shows that this debate veers toward the ideological and away from the empirical. By posting the truism that concrete is not the same as healthcare, and that Denmark is not the same as the United States, the committee is trying to marginalize, rather than learn from, an important and relevant article.

And second, more fundamentally, the T-shirt reveals that we lack the most basic understandings of how American healthcare markets operate, including the degree to which market information is beneficial. There is a comforting logic to thinking that healthcare markets conform to the theories taught in an economics undergraduate classroom, where markets operate smoothly and rationally. But it is equally comforting to think that American healthcare markets are exceptional and operate in ways that are antithetical to the laws of economics. Policymakers tend to occupy these polar extremes and participate in a dichotomous debate over whether healthcare markets work (or not). Both of these extreme positions, with their ideological parsimony, fit neatly onto T-shirts (did the HELP Committee say how the two markets are different? There wasn’t enough room on the shirt to say. But would they have bothered?). But those of us who think the answer is somewhere in the middle – that sometimes, the disclosure of information helps healthcare consumers shop intelligently, and sometimes it does not – need more than a T-shirt to explain.[5] This article tries to do that.

The Problem with Non-Disclosure

The prices that payers and providers negotiate have long been claimed to be trade secrets, and industry leaders have fought aggressively to keep them secret. It is hard to suggest that markets can work with this degree of opacity, just as it is hard to defend a regime that defends keeping prices unknown to the public. This is probably true in every market. In Flash Boys, Michael Lewis tells a story about a bunch of renegades on Wall Street who try to bring transparency to electronic high-frequency trading, a particularly impenetrable sector that Lewis argues has been exploiting consumers. Brad Katsuyama, one of the leaders of this upstart, said, “The fact that it is such an opaque industry should be alarming. The fact that the people who make the most money want the least clarity possible—that should be alarming, too.”

Katsuyama’s comment maps neatly onto how industry players reacted to the Administration’s proposal for greater transparency. Following the Trump Administration’s Executive Order, the American Hospital Association, the Federal of American Hospitals, the Rural Hospital Coalition, Association of American Medical Colleges, and the Association of Health Insurance Plans voiced strong opposition to the Administration’s transparency effort.[6] They succeeded in part when the Trump Administration shelved its transparency proposal.[7] However, the administration promised to revisit the rule, and it did.[8] During the last few months of the administration, the U.S. Department of Labor and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services finalized a rule requiring plans and insurers to disclose cost-sharing estimates to consumers ondemand.[9]

But even if opacity benefits the insiders that enjoy information advantages, it does not mean that disclosure of market information always benefits consumers. The question of whether more price transparency leads to better consumer behavior, and thus to lower prices and more competitive markets, is the question provoked by the Danish cement study, and it the question that might have answers in a careful assessment of the effects of information disclosure and dissemination on healthcare behaviors.

So, would transparency lead to more effective markets and more intelligent consumer behavior? Several states have already instituted price disclosure rules, forcing hospitals and payers to disclose prices. A good place to start is to evaluate the information that those laws disclosed and their effect on prices, consumers, and markets.

Pricing Transparency and Its Effect on Consumer Behavior

The Ugly: Posting Prices and Little More

California was among the first states to force pricing transparency[10] when it developed the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPOD).[11] Among the OSHPOD’s first initiatives was to construct a website that would collect and disclose the prices that hospitals charge.

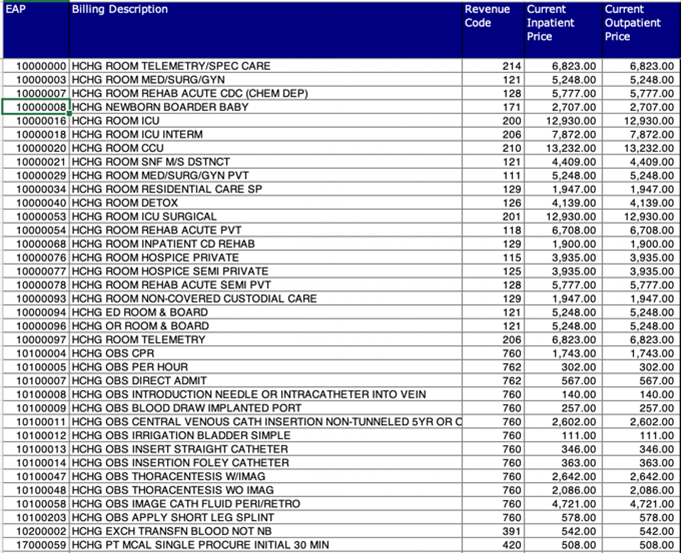

Sample price data from OSHPOD

The result, however, can only be described as a Kafkaesque. Price data is located behind tabs that are ambiguously named “Data & Reports” and “Topics.” The disclosed price data includes ten years of complex hospital chargemasters, which are lists of off-the-street prices for various hospital services. The consumer must download a large file to view each chargemaster, and they then are confronted with procedure codes that would even confound the physicians that perform those services. If this is what transparency looks like, then it is worth rethinking the entire strategy. Gathering the data might be useful for researchers, but it’s not useful for patients, and there is reason to conclude that industry is revealing itself to be hostile to the entire enterprise.

Massachusetts offers another venture into state-led transparency. To its credit, the state has invested significant legislative effort and political resources into gathering health price data, and the recently created Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA) and home to what is probably the most comprehensive All-Payer Claims Database in the nation.[12] But, even though CHIA offers more helpful information than the OSPHOD website, it, too, has produced disappointing results. In 2019, the Massachusetts Attorney General issued a comprehensive assessment of the state’s transparency efforts that concluded that those efforts have not controlled healthcare spending.[13] While remarking that “price transparency for consumers is essential,” the Attorney General called for “real solutions to control escalating costs.”[14] Evidently, disclosure alone did not constrain consistent price inflation, and there seems to be a disconnect between the transparency that states impose and the market effects they want to achieve.

These transparency failures, at the very least, should give caution to transparency enthusiasts. To be sure, they do not suggest that all transparency initiatives are ill-conceived – indeed, the theoretical underpinnings of transparency are compelling; markets simply cannot work if prices are entirely hidden. But a good theoretical argument should not fuel policy that is uninformed by empirical realities.

For the late Uwe Reinhardt, who many call his generation’s top health economist, and who I call perhaps the top economist-moralist, the failure of transparency initiatives to help patients caused enormous cause for alarm. He worried, consistent with discussions surrounding the HELP T-shirt ploy, that the transparency debate had devolved into an ideological fight, and that there was a growing danger that transparency proponents will be unswayed by facts. Reinhardt warned:

For the late Uwe Reinhardt, who many call his generation’s top health economist, and who I call perhaps the top economist-moralist, the failure of transparency initiatives to help patients caused enormous cause for alarm. He worried, consistent with discussions surrounding the HELP T-shirt ploy, that the transparency debate had devolved into an ideological fight, and that there was a growing danger that transparency proponents will be unswayed by facts. Reinhardt warned:

Consumer-directed health care so far has led the newly minted consumers of US health care (formerly patients) blindfolded into the bewildering US health care marketplace, without accurate information on the prices likely to be charged by competing organizations or individuals that provide healthcare or on the quality of these services. Consequently, the much ballyhooed consumer-directed health care strategy so far has been more a cruel hoax than a smart and ethically defensible health policy.[15]

It is worth repeating that Professor Reinhardt is an economist, and as such he believed that markets can work—that is, consumers acting on their own best interests can, as a collective, bring prices down if meaningful price information were genuinely available and intuitively accessible. But markets cannot work otherwise. And Professor Reinhardt warned that it is simply cruel to expose patients to a dysfunctional market. Perhaps this reflects the notion that market failures in healthcare are more devastating than market failures in other markets. Patients are vulnerable and easily exploited, and it is a moral failure to expect patients to survive market failures.

Some Modest Progress: “Shoppable” Services

Some states are finding more success. For example, early evidence shows that New Hampshire’s effort to make prices more transparent through its NH Healthcost website[16] have lowered some prices.[17] This is at least better than the Danish cement story.

In particular, one study revealed that after NH Healthcost disclosed prices for MRIs, prices decreased by 1% to 2% and overall spending for medical imaging (MRIs plus CT scans and x-rays) went down 3%.[18] This suggests that consumers needing MRIs shopped between available prices and gravitated toward lower prices, and that providers responded to consumer shopping by lowering prices. However, the study did not find any price decreases for other services.[19] To quote one of the authors of the study, “We don’t have evidence that this is a magic bullet . . . It seems to lead to some modest savings. The effects aren’t huge.”[20]

Nonetheless, the results indicate that something is moving in the right direction, that some services are indeed “shoppable.” The New Hampshire experience suggests that price transparency can make certain markets more competitive and can generate benefits for consumers, but that only some markets respond to transparency. Perhaps transparency efforts should focus specifically on services that people can shop for, such as MRIs, that are largely commodities and where alternative providers are easy to locate. Unfortunately, this is unlikely to meaningfully bend the cost curve, as relatively little will be gained if medical imaging ($94.7 billion in 2020, 2% of healthcare US expenditures[21]) are offered in competitive markets but hospital services ($1.27 trillion in 2020, 31% of US healthcare expenditures[22]) are not.

Perhaps consumer responsiveness to “shoppable” services justifies using copayments to encourage economizing behavior. Studies dating back to the Rand Health Insurance Experiment establish that consumers are sensitive to copayments, although this did not necessarily make them good shoppers, as higher copayments deterred individuals from seeking both appropriate and inappropriate care.[23] If insurance plans are constructed wisely, then even if patients are unlikely to learn of and respond to hospital prices, perhaps consumers will economize based on copayments and thereby seek appropriate care. One particular expression of this strategy—one that has had success reducing healthcare costs and stimulating price competition—is reference pricing. Reference pricing refers to health insurance products that offer standard coverage if a patient chooses cost-effective providers but require considerable cost sharing if more expensive alternatives are selected. Its advocates have described it as a change to the “choice architecture” and have reported that its short-term impact has been to shift patient volumes from hospital-based to freestanding surgical, diagnostic, imaging, and laboratory facilities.[24]

Reference pricing—and any strategy that employs cost-sharing to encourage economizing behavior—rests on the heavy assumption that insurance products will be designed with economizing behavior in mind. It is a response to the less refined argument for price disclosure since it pays primary attention to the prices (i.e. copayments) that consumers confront and can readily see. To work on a population scale, these strategies rely on insurers to be efficient intermediaries. Perhaps insurers would be better intermediaries if hospitals were required to disclose prices, though it is more likely that insurers prefer prices to remain hidden. Reference pricing therefore is more likely to emerge as an alternative if consumers—not insurers—demand it.

Another justification for pursuing price transparency is that it will encourage the development of shopping tools that will make more services “shoppable.” In other words, even if consumers cannot obtain and understand hospital prices, they can understand information gathered and presented by search devices. Some websites, such as New Choice Health[25] and Castlight, gather price data from the OSHPOD and similar, normally impenetrable sites and then give consumers and insurance enrollees their expected copay for certain services at different locations. Thus, they synthesize price data related to alternative points of service and present them in an intuitive format. This converts the abstruseness of the chargemaster into a format that is more akin to how Google Maps displays prices at gas stations.

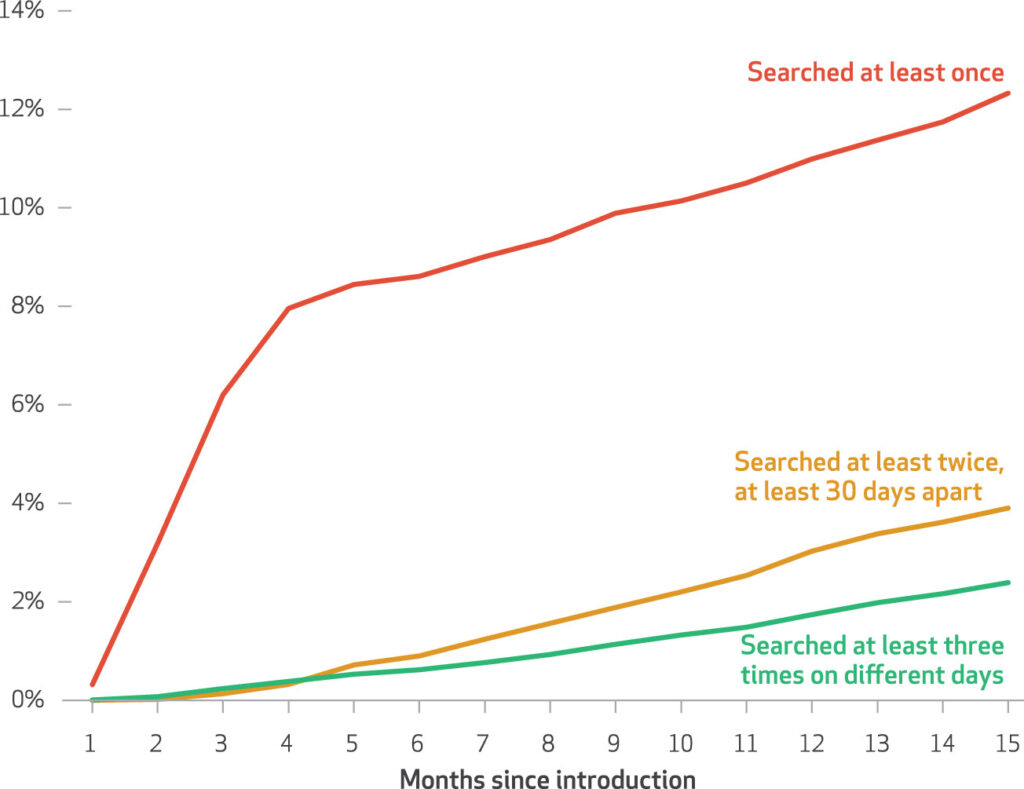

Studies that have examined the effects of these price transparency tools suggest that they also are not a silver bullet. A Health Affairs study from 2017 examined consumer use of a transparency tool offered by Castlight and its market effects.[26] It found that some sizable portion of participants used the price tool, but the vast majority of those who used it did so only once, and only a small population of participants used the price tool regularly.[27] Accordingly, the overall savings from Castlight were minimal.[28] This is consistent with other studies, which have found that even when shopping tools or other consumer-oriented intermediaries enable patients to shop for services, most prefer to follow their doctors’ recommendations.[29] It seems that even the combination of shopping tools and price transparency—circumstances where shopping is as simple as possible for consumers—does little to induce shopping behavior.

Effects of a Transparency Tool (Desai, et al., 2017)

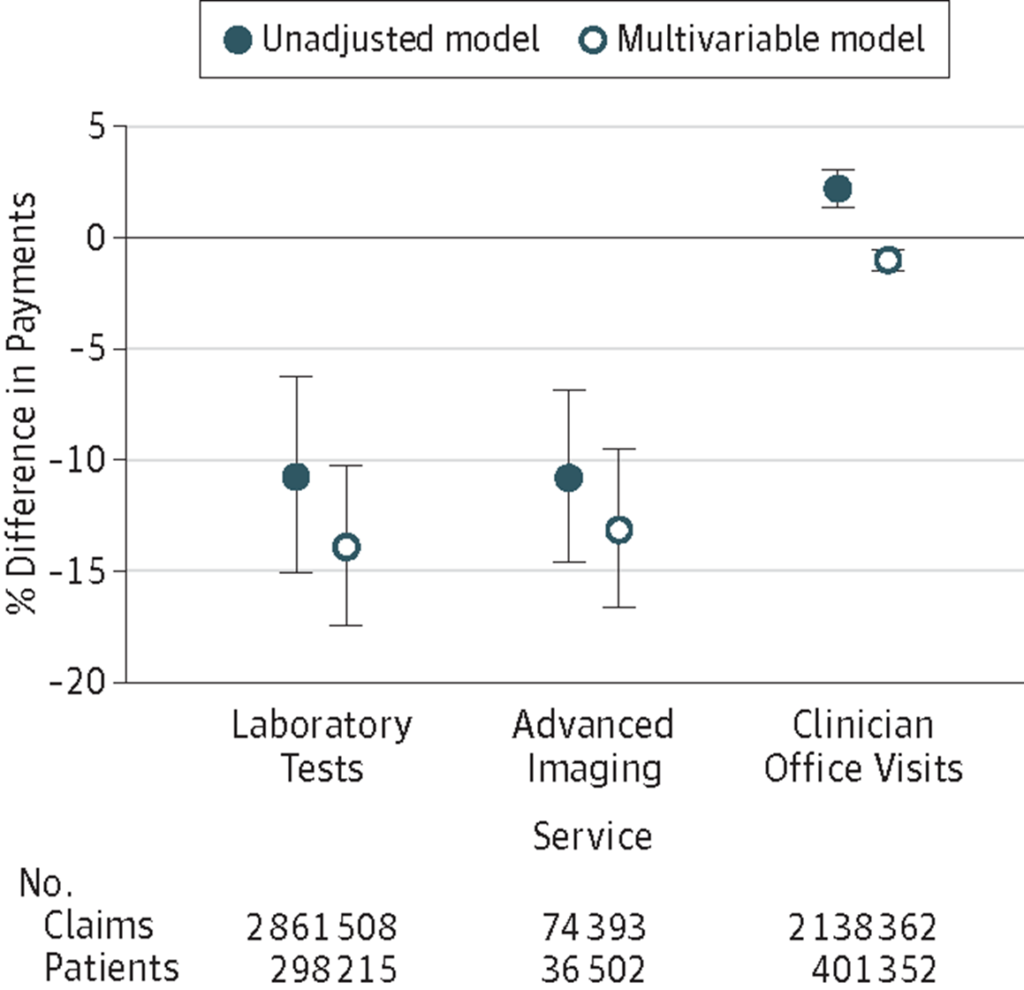

In a similar 2014 study, researchers evaluated the effects of a mobile app price tool offered by Castlight Health.[30] Like the 2017 study of the Castlight website, this study looked at whether individuals used the app and whether obtaining information about higher quality and lower cost services affected consumer behavior. The reported results, which examined effects on laboratory tests, imaging services, and clinical office visits, were modest, but they nonetheless offer some promise for shopping that is consistent with other research: first, the Castlight Health price tool reduced prices for laboratory tests down about 10% to 15%, or by about $3; second, the tool reduced on prices for advanced imaging services, such as MRIs also by about 10% to 15%, or by about $75 to $100; and third, the tool had a minimal effect on prices for the clinical office visits.[31] In sum, consistent with findings from New Hampshire’s Healthcost initiative, the price tool apparently stimulates some price competition in certain markets, but the effect is small and only was evident in markets for laboratory or imaging services.

Effects of Price Transparency on Diagnostics vs Clinical Visits (Whaley, et al., 2014)

More recent research, however, suggests that price transparency tools might be counterproductive; instead of inducing consumers to shop for lower cost services, they might induce providers to increases prices. A study published in 2021 examining the impact of a price transparency tool sponsored by New York State, found that prices increased for certain imaging services, which are always insured and rarely elective, while decreased for psychology and chiropractic services, which are less often insured and more elective.[32] Moreover, the pricing tool’s upward influence on prices outweighed the tool’s comparatively weaker effect on consumer price shopping.[33] Thus, it seems that the Danish cement experience does translate, at least in some circumstances, to American health markets. The authors of the 2021 study, like the authors of the Danish cement research, could not determine why transparency led to higher prices, but they speculated about two possible mechanisms: (1) transparency could enable providers to tacitly collude, or (2) transparency informs low-price providers that their prices are below market averages, prompting them to increase their rates to match their competitors’.[34]

The collection of studies offers mostly uninspiring results. Some healthcare services, like lab tests and imaging services, are shoppable because they are commoditized, rudimentary, readily available at multiple locations. But even for these services, transparency reduces prices only modestly, and they don’t represent the existential cost problems in the United States. For services that occupy a greater portion of our national spend, such as clinician and hospital services,[35] transparency efforts appear to have little impact, even when navigation tools are available.[36]

Even though price transparency efforts have yielded unsatisfying results, it cannot mean that lack of transparency is better. Instead, as professor Dr. Sherry Glied recognized, price transparency “is best understood as an intermediate stage in the policy process.”[37] The challenge begins, not ends, with arming consumers with information. There is much remaining work, after transparency, in structuring meaningful choice within workable markets.

Another Kind of Transparency: Shaming

Maybe there are other ways to use transparency to force markets to respond. One example is a story that started in 2000, when the Institute of Medicine released a publication called To Err is Human, reporting that “as many as 98,000 people die in any given year from [conditions contracted because of] medical errors that occur in hospitals.”[38] Just to be clear, these deaths are consequences of mistakes or hospital-acquired conditions (HACs). The Institute of Medicine concluded that “[i]t would be irresponsible to expect anything less than a 50 percent reduction in errors over five years.”[39]

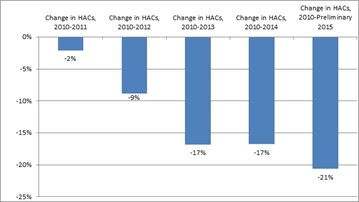

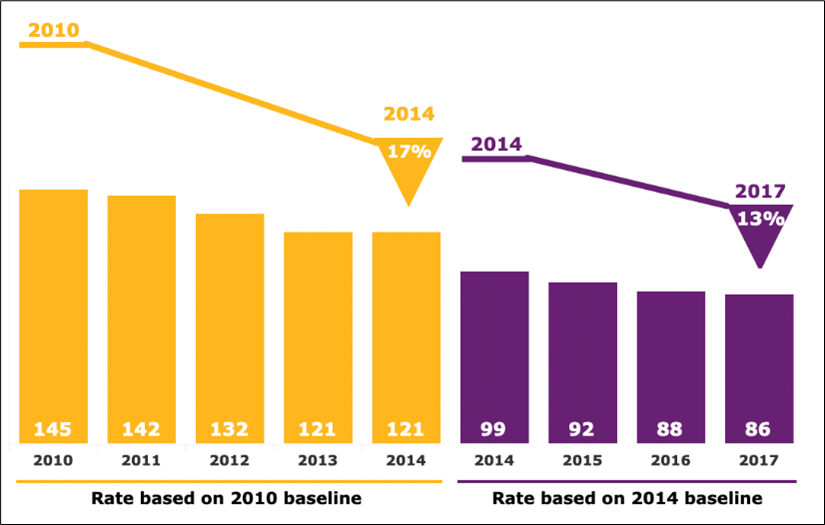

The publication was widely influential in academic circles but unfortunately triggered few improvements in care delivery, and thus hospital-acquired conditions continued at around the same rate for the next decade. But improvements were triggered in 2011 when the Affordable Care Act (ACA) implemented its Partnership for Patients.[40] The program has three main elements. First, hospitals could be financially penalized for HACs.[41] The government could decline to reimburse, partially reimburse, or fine a hospital whose patient gets an HAC and requires treatment.[42] Second, hospitals were given technical assistance to improve their quality management and quality assurance.[43] And third, hospital-level HACs were publicly reported, so hospital administrators could see how they compared to their peers.[44] It became known how many preventable deaths fell to each hospital.

care delivery, and thus hospital-acquired conditions continued at around the same rate for the next decade. But improvements were triggered in 2011 when the Affordable Care Act (ACA) implemented its Partnership for Patients.[40] The program has three main elements. First, hospitals could be financially penalized for HACs.[41] The government could decline to reimburse, partially reimburse, or fine a hospital whose patient gets an HAC and requires treatment.[42] Second, hospitals were given technical assistance to improve their quality management and quality assurance.[43] And third, hospital-level HACs were publicly reported, so hospital administrators could see how they compared to their peers.[44] It became known how many preventable deaths fell to each hospital.

Source: www.innovation.cms.gov

Reductions in HACs after Partnership for Patients program (Source: AHRQ)

It seems that the Partnership for Patients program has produced results, and it illustrates another transparency strategy that could work. One might call it shaming. Rather than telling consumers where they could save a dollar, these data instead show where people died. The success of this experience, in conjunction with the disappointing results from other transparency experiments, might suggest that patients are more responsive to death risks than to opportunities to save money; or it might suggest that physicians are more motivated by threats to their reputation than patients are to opportunities to economize, and thus transparency efforts should target physician esteem rather than consumer budgets. Regardless, if policymakers are ever to harness the power of markets, there needs to be good science on how information affects behavior. Perhaps these assorted results can help.

Other Opportunities to Shop: Consider Selecting Health Insurance

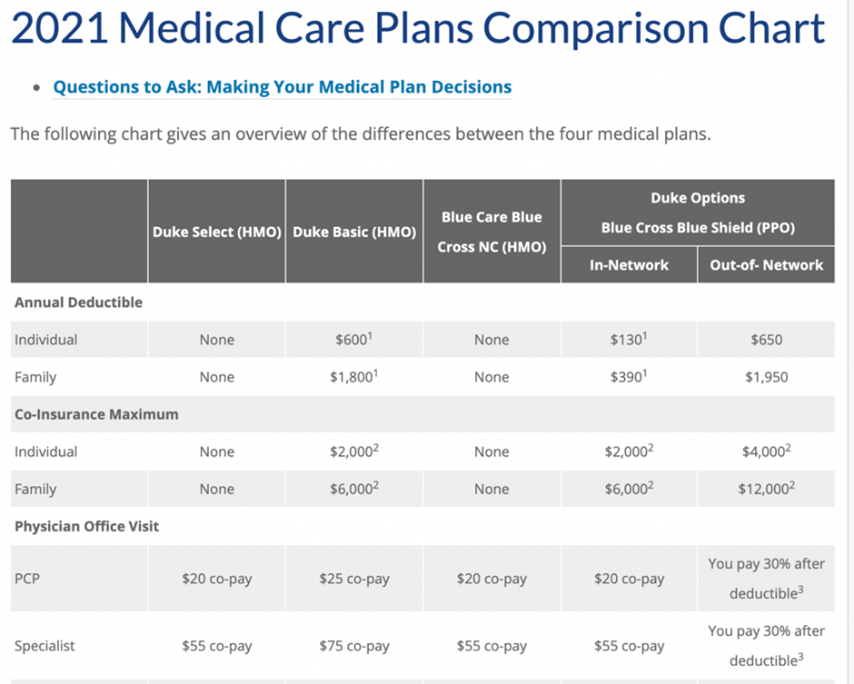

There are other ways that consumers might be able to shop. For example, most Americans get their health insurance through their employers, and most of those employees select among different health insurance offerings every year. In fact, this annual selection of health insurance is usually a robust exercise in choice: different insurance products are presented in a framework that is both intuitive and substantive for employees. The plans’ differences in price and coverage are explained carefully, and employees generally have a meaningful opportunity to act as an informed consumer.

A typical example is illustrated in the graph below, in which an employer’s publication during open enrollment presents four alternative insurance plans.[45] The employee handbook spells out the details of each plan, including a basic set of prices and the monthly employee contributions.[46] Indeed, one could imagine similar tables for other services—MRIs, x-rays, and other screening services—to enable meaningful patient shopping and to facilitate greater price competition in other markets.

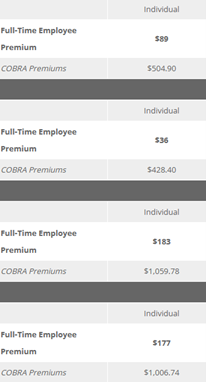

Source: Duke Human Resources

However, the accompanying table that includes the monthly premiums for each plan also illustrates how insurance plan selection actually prevents genuine price competition from taking place.[47] Note that from the employee’s perspective, the annual premiums for the most expensive and least expensive plans are less than $1,800 apart: annual premiums for the least expensive plan is $432 ($36×12) while the most expensive is $2,195 ($183×12). But focusing only on what the employee faces hides the full cost of the insurance. The true cost difference between the two plans, based on the COBRA premiums, is $7,576.56 ($1,059.78×12 – $428.40×12).

The discrepancy between perceived price and actual price emerges because employers do not advertise that the employee’s direct contribution is only part—usually around one quarter—of the total cost of health insurance.[48] Critically, the employee also pays for the employer’s contribution to health insurance, albeit indirectly through reduced take-home wages. So, in the above example, the employee is likely to think she is paying only $2,195 for the most generous insurance plan, whereas she really is paying the full $12,717.36.[49]

If she knew she were paying for the full amount, would she be more vocal in asking for less expensive options, and would she shop more aggressively? If she knew that she were spending nearly $13,000, would she prefer to spend those dollars in other ways?

Professor Regina Herzlinger, who is often called the godmother of consumer-driven healthcare,[50] has frequently argued for using the annual purchase of health insurance to expose individuals to a broad menu of options. In work with coauthors,[51] she suggests giving employees control over their full contributions to health insurance; after they purchase a qualifying insurance plan, they may use any remaining funds for any other purpose, including converting the remainder into taxable take-home pay.[52] Not only might this allow individual employees to spend their limited resources in ways that best address their many financial needs, but it also exposes the market directly to price-sensitive employees. The market will be rewarded if it responds to consumer demands for affordable options, and consumer shopping opportunities will generate benefits throughout the economy.

Professor Regina Herzlinger, who is often called the godmother of consumer-driven healthcare,[50] has frequently argued for using the annual purchase of health insurance to expose individuals to a broad menu of options. In work with coauthors,[51] she suggests giving employees control over their full contributions to health insurance; after they purchase a qualifying insurance plan, they may use any remaining funds for any other purpose, including converting the remainder into taxable take-home pay.[52] Not only might this allow individual employees to spend their limited resources in ways that best address their many financial needs, but it also exposes the market directly to price-sensitive employees. The market will be rewarded if it responds to consumer demands for affordable options, and consumer shopping opportunities will generate benefits throughout the economy.

This idea made its way through the Trump administration. In 2019, the administration finalized a rule permitting certain employees to use employer-funded health reimbursement accounts (HRAs) to purchase qualifying insurance on the individual market.[53] HRAs are designed both to allow employees to economize on health insurance dollars and to use any remaining dollars in other ways, and it has real promise for injecting useful competition into healthcare markets.

This approach also might offer broader lessons on how consumers can fruitfully shop. Although it is difficult to shop for individual knee replacements, it is not so difficult to shop for insurance plans. Consumers do that annually and are familiar with the available options. It would be wise to structure insurance options within a useful information context: perhaps requiring disclosure of the plans’ actuarial value and an insured’s total expected costs with each; or requiring plan comparisons (beyond merely premiums) or providing tools for consumers to evaluate the merits of each plan at the time they purchase insurance. Additional research is needed to confirm whether consumers make good choices for themselves and for the market when they shop for insurance, and what choice architectures encourage good decisions. But because consumers routinely purchase insurance within these frameworks, and because this is a purchase that is not made under duress or after an illness has already emerged, there is little reason to think that shopping will lead to the harms feared by Professor Reinhardt. Instead, it would be wise to inform consumers and to harness these market energies.

Preliminary Conclusions: Creating Opportunities to Shop

Can we be good consumers? The collective evidence offers a nuanced answer: sometimes.

One lesson is that consumers cannot do it on their own, and that a set of rigorous market settings is necessary. Markets only work if they offer adequate choices. They only work if consumers have useful information. They only work if they rest atop an intuitive framework and a familiar setting within which those choices and that information are presented. And, even with all these prerequisites, they still might require navigators or other intermediaries to walk consumers through the process and make comparisons easy, and they might require baking in some forgiveness as consumers inevitably make mistakes.

So, is healthcare like Danish cement? No. But it is not so dissimilar from it either. Markets work, but they cannot work on their own. We should not embrace laissez-faire economics as an ideological or theoretical matter, but if we help consumers walk through the complexities, then maybe for some services we can bring some competitive energies and some real social value.

The Opposite of Shopping

What is the opposite of shopping? This might be an even more important question about healthcare.

The opposite of shopping is best epitomized by what we now call “surprise bills.” Surprise bills occur when a patient receives healthcare and later is issued a bill that exceeds the prevailing market price. For example, a patient goes to an emergency room complaining of a headache, the ER staff then administers an MRI, and later the hospital sends the patient a bill for $5,000. The ER staff did not inform the patient of the price before the diagnostic was administered, and the charged price – $5,000 – is far more than any insurer pays.

Surprise billing has become a common strategy by providers, mostly hospitals, to raise revenue and to force patients and insurers into their network. It is often justified as a mechanism to compensate for low reimbursements or to flex market power, but the unavoidable tragedy is that it targets and exploits the vulnerable. As Professor Reinhardt noted, consumers are vulnerable when they cannot know prices in advance. Perhaps more important, consumers are uniquely vulnerable when they enter a healthcare setting as patients.

Why are surprise bills the opposite of shopping? Shopping implies agency: autonomy, deliberateness, and an awareness of the surrounding market.

The lack of shopping is not the lack of agency since deciding not to shop can be consistent with having agency – one can rationally decide to forego the expenses and benefits of searching for better prices. But surprise bills deny agency precisely because they deny patients the opportunity to learn from and respond to the environment around them. They exploit a lack of information and deny any opportunity to act autonomously.

The lack of shopping is not the lack of agency since deciding not to shop can be consistent with having agency – one can rationally decide to forego the expenses and benefits of searching for better prices. But surprise bills deny agency precisely because they deny patients the opportunity to learn from and respond to the environment around them. They exploit a lack of information and deny any opportunity to act autonomously.

With the passage of the No Surprises Act, policymakers have collectively condemned surprise bills and have taken measures to bring them to an end. But the moral criminality – and I use that language advisedly – of the practice still has not been adequately articulated. In a series of articles with Kevin Schulman and Mark Hall, I have tried to describe why agency is central to delivering healthcare and why surprise bills are a foundational transgression. In 2012, we introduced the term “informed financial consent” to convey the importance of making sure patients were aware of the financial burdens they were incurring in seeking care.[54] We observed the unfortunate irony that the healthcare sector places a premium on informed consent but very little on informed financial consent:[55] providers assiduously seek a patient’s assent before the performing a procedure, but if the patient asks how much the procedure costs, providers usually say that they do not know, and that their ethical obligation is only to inform patients of the health risks but not the financial consequences. In later articles, we expressed the hope that the No Surprises Act would not just protect patients from exploitive billing practices but also advanced their autonomy, dignity, and agency,[56] and that the canon of medical ethics would recognize both financial informed consent and the realities of financial toxicity as central to the practice of medicine.

Agency and Health

The centrality of agency in healthcare extends beyond the sector’s financial practices—not just whether shopping is possible, prices are hidden, and patients can act as informed consumers—but to most every aspect of healthcare. The notion of agency is relevant every time patients interact with the health sector.

First, scholars have identified the importance of agency in health. Literal control over aspects of one’s environment improves health outcomes, such as asserting control over daily routines and physical spaces, and assorted studies confirm that giving patients—especially the elderly—even rudimentary elements of control can improve health outcomes.[57] Researchers have also found that patients exhibit worse health outcomes when they lacked privacy, heard outside noises, and could not control the television in their hospital rooms.[58]

More broadly, it is known that additional years of education improve health outcomes, even when controlling for income, job status, insurance status.[59] Many think that one reason is that more education leads to greater agency: greater education offers status and autonomy and therefore more control our lives. Status and autonomy also contribute more specifically to beneficial engagements with healthcare providers.

Could shopping—the mere opportunity to exercise agency and shop—improve health outcomes on its own? And could the opposite of shopping worsen health outcomes? We must take seriously the notion of shopping, not just through the economic lens of consumers and prices, but also through the potential enhancement of agency and autonomy in the health care sector. This notion could offer an enormously powerful tool, but the broader concept remains largely underappreciated and unexplored.

Conclusion: A(nother) Picture is Worth 1,000 Words

The moral imperative and the substantial health benefits of expanding agency in medicine does not mean that doing so will be easy. There are certain situations where patients are reasonably told to forego agency. There are also many doctor-patient interactions where it is unreasonably difficult for patients to assert agency.

One such example occurred to me recently, and this offers another opportunity to share a picture: this is me, in May 2019, shortly after I was just discharged from the hospital after undergoing heart surgery. I am not the first person to have undergone a medical experience to then write about it, nor am I the first health policy scholar to have had a medical encounter affect policy ideas or a research agenda. But my experience was illustrative in the challenges of achieving meaningful agency in healthcare.

One such example occurred to me recently, and this offers another opportunity to share a picture: this is me, in May 2019, shortly after I was just discharged from the hospital after undergoing heart surgery. I am not the first person to have undergone a medical experience to then write about it, nor am I the first health policy scholar to have had a medical encounter affect policy ideas or a research agenda. But my experience was illustrative in the challenges of achieving meaningful agency in healthcare.

Despite being an expert in contracts law and health policy, I was struck by the enormity of my informational disadvantage when I was admitted for my surgery. The admissions contract I signed read, “You are here for mitral valve surgery, replacement/repair.” Because the hospital staff could not tell me in advance whether a repair was possible or a replacement was necessary, it could not be more specific. The second line said, “I agree to everything that is deemed to be medically necessary or appropriate to fulfill this service.” It said nothing about any details that involve significant surgical decisions, and I was not consulted about any of them. The contract was nearly as vague as a blank cheque. When I rent a car for two days at AVIS, I have a four-page contract. This was one page for open heart surgery and five days in the hospital.

I do not know if there is a better contract out there or if more contract specificity is advisable. I do not know if the doctor should have asked me in advance if I would prefer the heart bypass machine go through the chest or the groin, or if I would have preferred a reinforcement ring to go entirely or just mostly around the valve. I suppose the surgeon could have intelligently presented all these options to me, allowed me to research those options, and then let me participate in shared decision-making. But that is not the way our health system works, and I am not entirely sure that it should.

Can we shop for MRI services? Yes, though it will require a market that is committed to flexibility, transparency, and consumer engagement. Is that going to bring healthcare costs down? If at all, probably minimally. Can we shop for insurance? Yes, and perhaps there can be genuine savings, though again it would require a market structure that provides intuitive and meaningful consumer choice. Can we shop for heart surgeries, or other complex inpatient care? Very unlikely, even though inpatient care constitutes the largest spend.

But can we more meaningfully incorporate agency into healthcare? It’ll be hard, but it’s essential to engage in these larger and often intractable questions. Enabling consumers to shop is not just a means to reduce healthcare costs, it also allows patients to have agency when they engage in the health sector. That brings material benefits and is a moral imperative. And it highlights that, as with so much else in healthcare, science and markets are inseparable from deep ethical challenges.

References

[1] Exec. Order No. 13877, 84 Fed. Reg. 30,849 (June 27, 2019).

[2] Jennifer Bresnick, Verma: Price Transparency Rule a “First Step” for Consumerism, Health Payer Intelligence (Jan. 11, 2019), https://healthpayerintelligence.com/news/verma-price-transparency-rule-a-first-step-for-consumerism; see also Seema Verma, Administrator, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Remarks at the America’s Health Insurance Plan’s 2019 National Conference on Medicare (Sept. 24, 2019), https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/remarks-administrator-seema-verma-americas-health-insurance-plans-ahip-2019-national-conference (“We believe in a healthcare system in which patients – not the government – are empowered with choice and control, price and quality transparency . . . . When consumers have choices and are empowered with information, businesses deliver value to attract customers to succeed.”)

[3] See, e.g., Bipartisan House and Senate Committee Leaders Announce Agreement on Legislation to Lower Health Care Costs, U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions (Dec. 8, 2019), https://www.help.senate.gov/chair/newsroom/press/bipartisan-house-and-senate-committee-leaders-announce-agreement-on-legislation-to-lower-health-care-costs- (noting bipartisan agreement on legislation to require greater price transparency).

[4] Svend Albæk, Peter Møllgaard, & Per B. Overgaard, Government-Assisted Oligopoly Coordination? A Concrete Case, 45 J. Indus. Econ. 429–433 (1997).

[5] When The New York Times addressed the issue, it said, “It makes intuitive sense—publish prices negotiated within the health care industry, and consumers will benefit.. . . [G]ive patients more information about what health care will cost before they get it.” It then quoted one of the authors of the Danish concrete study who succinctly said, “I’m sure there are some similarities between pricing of various health care services and ready-made concrete in Denmark in the early 1990s . . . but I’m also sure there might be huge differences.” Margot Sanger-Katz, Why Transparency on Medical Prices Could Actually Make Them Go Higher, N.Y. Times: Upshot (June 24, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/24/upshot/transparency-medical-prices-could-backfire.html

[6] Kelly Gooch, Hospitals Slam CMS Proposal to Disclose Negotiated Rates, Becker’s Hospital Review: Becker’s Hospital CFO Report (Sept. 30, 2019), https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/hospitals-slam-cms-proposal-to-disclose-negotiated-rates.html.

[7] Bob Herman, Trump Administration Punts Hospital Price Transparency Rule, AXIOS (Nov. 1, 2019), https://www.axios.com/trump-punts-hospital-price-transparency-rule-c90b7ab5-a865-470f-b954-42927022eb2e.html.

[8] Id.

[9] Katie Keith, Verma: Trump Administration Finalizes Transparency Rule for Health Insurers, Health Affairs (Nov. 1, 2020), https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20201101.662872/full/.

[10] See April Dembosky, California Governor Signs Law To Make Drug Pricing More Transparent, NPR: Shots Health News From NPR (Oct. 10, 2017), https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/10/10/556896668/california-governor-signs-law-to-make-drug-pricing-more-transparent (noting that in October 2017, “California Gov. Jerry Brown . . . sign[ed] the most comprehensive drug price transparency bill in the nation that will force drug makers to publicly justify big price hikes”).

[11] Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, https://oshpd.ca.gov/ (last visited July 09, 2021).

[12] Center for Health Information and Analysis, https://www.chiamass.gov/ (last visited July 10, 2021).

[13] https://www.mass.gov/doc/examination-of-health-care-cost-trends-and-cost-drivers-2019 (“The new report finds online pricing tools that allow patients to compare the cost of certain health care services may provide patients with useful information, but they fail to control health care spending. According to the report, these websites are used by only a tiny fraction of residents and are not influencing consumer decision-making in a meaningful way.”)

[14] Press Release, Office of Attorney General Maura Healey, AG Healey: Online Pricing Tools & Alt. Payment Arrangements are Not Enough to Contain Health Care Costs (Oct. 17, 2019), https://www.mass.gov/news/ag-healey-online-pricing-tools-and-alternative-payment-arrangements-are-not-enough-to-contain

[15] Uwe E. Reinhardt, Health Care Price Transparency and Economic Theory, 312 JAMA 1642–43 (2014).

[16] New Hampshire Insurance Department, Compare Health Costs & Quality of Care, NH HealthCost, https://nhhealthcost.nh.gov/ (last visited July 9, 2021).

[17] See Zach Y. Brown, Equilibrium Effects of Health Care Price Information, 101 Rev. Econ. & Stats. 699 (2019); Melanie Evans, One State’s Effort to Publicize Hospital Prices Brings Mixed Results, Wall St. J. (June 26, 2019), https://www.wsj.com/articles/one-states-effort-to-publicize-hospital-prices-brings-mixed-results-11561555562 (noting that the price data “has helped lower prices somewhat” but that “few people have used New Hampshire’s site, which researchers say has reduced its impact on prices and costs”).

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/us-imaging-services-market

[22] National Health Expenditure Accounts, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical

[23] Robert Brook, et al., The Effect of Coinsurance on the Health of Adults Results from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment, Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1984. https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R3055.html

[24] https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1256

[25] New Choice Health, https://www.newchoicehealth.com/ (last visited July 9, 2021).

[26] Sunita Desai et al., Offering a Price Transparency Tool Did Not Reduce Overall Spending Among California Public Employees and Retirees, 36 Health Affairs 1401–1407 (2017).

[27] See id. at 1404 fig.1 (noting on a graph that by month 12, over 12% of participants had used the price tool at least once, about 4% of participants had used the tool twice at least thirty days apart, and about 2% had used it three times on different days).

[28] See id. at 1405 fig.2 (noting on a graph that the control price is consistently and slightly higher).

[29] Sherry Glied, Price Transparency—Promise and Peril, 325 JAMA 1496–97 (2021).

[30] Christopher Whaley et al., Association Between Availability of Health Service Prices and Payments for These Services, 312 JAMA 1670–76 (2014).

[31] Id. at fig.1.

[32] Hunt Allcott et al., The Impact of Price (Charge) Transparency in Outpatient Provider Markets, E-Health Conference 1–46 (Apr. 4, 2021), https://www.ehealthecon.org/pdfs/Glied.pdf.

[33] Id. at 5.

[34] Id.

[35] See NHE Fact Sheet, CMS.gov, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet (last updated Dec. 16, 2020) (noting, for example, that of the $3.8 trillion spend on health care in 2019, $772.1 billion was spent on physician and clinical services).

[36] Sherry Glied, supra note 26.

[37] Sherry Glied, supra note 26.

[38] Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System (Linda T. Kohn et al. 2000).

[39] Id.

[40] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Partnership for Patients, CMS.gov, https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/partnership-for-patients (last updated June 24, 2021).

[41] Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, Project Evaluation Activity in Support of Partnership for Patients: Task 2 Evaluation Progress Report, CMS.gov 17 (July 10, 2014), https://innovation.cms.gov/files/reports/pfpevalprogrpt.pdf (noting that “Section 3008 of the ACA . . . provides for payment penalty based on high rates of hospital-acquired conditions, beginning in fiscal year (FY) 2015”).

[42] Id.; Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111–148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010).

[43] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, supra note 41.

[44] Id. See also AHRQ National Scorecard, at https://www.ahrq.gov/hai/pfp/index.html

[45] See 2021 Medical Care Plans Comparison Chart, Duke Human Resources, https://hr.duke.edu/benefits/medical/medical-insurance/plan-comparison (last visited July 10, 2021) (noting five plans available for Duke employees).

[46] Id.

[47] See Monthly Medical Premiums (2021), Duke Human Resources, https://hr.duke.edu/benefits/medical/medical-insurance/premiums (last visited July 10, 2021) (stating that $295 is the lowest 2021 monthly premium for employee/children and $446 is the highest, which is an annual difference of $1,812).

[48] Regina E. Herzlinger, Barak D. Richman, & Richard J. Boxer, How Health Care Hurts Your Paycheck, N.Y. Times (Nov. 2, 2016), https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/02/opinion/how-health-care-hurts-your-paycheck.html.

[49] Id.

[50] “Herzlinger: The Godmother of Consumer-Driven Health Care,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-TXDyr0mQnY

[51] HBR, Working paper.

[52] Herzlinger et al., supra note 47.

[53] Kathy Hempstead, The HRA Rule Could be a Game Changer for Health Insurance, STAT (Oct. 22, 2019), https://www.statnews.com/2019/10/22/hra-rule-health-insurance-individual-market/.

[54] Barak D. Richman et al., Overbilling and Informed Financial Consent—A Contractual Solution, 367 New Eng. J. Med. 396–97 (2012).

[55] Id. at 396.

[56] Barak D. Richman et al., The No Surprises Act and Informed Financial Consent, 385 New Eng. J. Med. 1348–51 (2021).

[57] Barak D. Richman, Behavioral Economics and Health Policy: Understanding Medicaid’s Failure, 90 Cornell L. Rev. 705, 741-43 (2005). See also, e.g., Roger S. Ulrich, supra note 60; Roger S. Ulrich, Effects of Interior Design on Wellness: Theory and Recent Scientific Research, 3 J. Health Care Interior Design 97–109 (1991); Douglas Raybeck, Proxemics and Privacy: Managing the Problems of Life in Confined Environments, in From Antarctica to Outer Space: Life in Confined Environments 317–30 (1987).

[58] Ann Sloan Devlin & Allison B. Arneill, Health Care Environments and Patient Outcomes: A Review of the Literature, 35 Env’t & Behav. 665–94, 672 (2003) (citing Roger S. Ulrich, How Design Impacts Wellness, 35 Healthcare F. J. 20–25 (1992)).

[59] Les Picker, The Effects of Education on Health, Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Rsch.: Digest (Mar. 2007), https://www.nber.org/digest/mar07/effects-education-health.