Austin J. Allen, UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School, UNC School of Medicine, and Markus Saba, UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School, UNC Center for the Business of Healthcare

Contact: Markus_Saba@Kenan-Flagler.UNC.edu

Abstract

What is the message? Prior authorization has evolved from a method of controlling cost into a complex system that payors utilize to manage and regulate care. This has become an emotionally charged headline fueled by accounts of payors negatively impacting clinical care outcomes. This article provides a comprehensive, high-level overview about the status and future direction of prior authorization and concludes with a cautionary note that, in attempts to streamline prior authorization, close collaboration between all stakeholders is required to avoid inadvertently increasing the burden on healthcare providers and patients.

What is the evidence? A review of prior authorization in U.S. healthcare, accomplished via a combination of primary interviews with industry and government stakeholders alongside secondary literature review of both academic journals and news media.

Timeline: Submitted: January 17, 2023; accepted after review March 28, 2024.

Cite as: Austin Allen, Markus Saba. 2024. A Review on the Role of Prior Authorization in Healthcare and Future Directions for Reform. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.HMPI.org), Volume 9, Issue 1.

Introduction

Prior authorization. This has become a healthcare buzzword in the setting of emotionally charged headlines about patients not receiving care, proposed legislative changes, and a myriad of responses from health insurers, providers, and patients.

Before diving into this issue, it is critical to answer the question “What is prior authorization?” In the simplest terms, prior authorization is a mechanism utilized by payors which requires approval from the payor before a healthcare service is rendered in order to obtain reimbursement for the service. The purpose of prior authorization is widely accepted to be preventing overutilization of healthcare services as a means of controlling cost. While the general purpose of prior authorization is a matter that most stakeholders can agree with, the logistics and application of prior authorization have evolved into an extremely complicated system. The administrative burden of prior authorization for healthcare providers alone was estimated to cost between $23 and $31 billion annually1 in 2009 for outpatient physicians. Legal battles have also emerged, challenging whether insurers are utilizing prior authorization to protect their own economic interests above the interests of the patients they have contracted to provide healthcare insurance.2,3

One important distinction to make with prior authorization is the difference in process / motivation for pharmaceuticals versus services (ex: surgical procedures). For pharmaceuticals, payors may introduce step-tiered therapy to direct patients towards lower cost or higher discount medications as the first line of therapy. In most scenarios, healthcare providers bear the burden of coordinating this administrative process with no financial incentive, as their payment is tied to medical decision making, not which medication is prescribed. In the setting of prior authorization for services like a surgical procedure, prior authorization exists to ensure all appropriate lower risk/lower cost measures have been exhausted. Financial incentives with services are aligned with the healthcare provider directly involved, as the provider requesting authorization stands to receive payment if the prior authorization is approved and services are provided.

In the setting of ongoing changes with prior authorization, the goal of this article is to synthesize the current landscape of prior authorization. In this review article, included is a summary of the stereotyped perspectives stakeholders commonly have about prior authorization, evidence examining the impact of prior authorization, ongoing legislative initiatives, and additional recommendations that could improve the prior authorization process for all stakeholders.

Stereotyped Perspectives

Payors: It is important to note that in the setting of the U.S. economy with the world’s largest healthcare expenditure, payors are one of the few stakeholders directly incentivized to reduce total healthcare cost. Healthy patients who don’t utilize services are a financial benefit for payors.

At the simplest level, payors utilize prior authorization to decrease the cost of healthcare by preventing use of unnecessary services. Rather than reimbursing any and every service rendered, prior authorization can be used as a rationing mechanism to ensure that the services utilized by patients are appropriately indicated. Indeed, most payors publish guidelines regarding which services are eligible for reimbursement, as well as the requirements for obtaining reimbursement. However, it is important to note that while guidelines are published, they may be inconsistent from insurer to insurer, and are difficult to locate online.4

Another important role of prior authorization for payors is directing patients to lower cost or higher margin services in a step-tiered manner. For example, patients with back pain may be required to undergo less invasive therapy like physical therapy before undergoing surgery. While the goal may be reducing overall utilization of services, step-tiered therapy becomes even more complicated, but potentially more lucrative, for managing pharmaceutical prescriptions. Payors may direct patients to lower-cost medication classes as a primary treatment modality before authorizing more expensive (and novel) treatment mechanisms. Similarly, patients may be directed to lower-cost or higher margin medications within the same class of drugs, based on which medication the payor has negotiated the best rate. Ultimately, payors are incentivized to steer patients towards the medication that achieves the best outcome at the most cost-effective price.

Pharmaceuticals: Pharmaceutical companies have a mixed relationship with prior authorization. On one hand, with a financial incentive to sell as many medications as possible at the highest margins, barriers like prior authorization theoretically detract from maximum prescriptions and profit. However, even though prior authorization may decrease net market availability, strategically negotiated relationships through pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) may result in prior authorizations steering an increasing client share to a company’s drug product over competitors, albeit at a lower negotiated rate than list price.

Adding an additional layer of complexity to a pharmaceutical company’s view on prior authorization is that in some therapeutic areas, profit can be maximized by altogether avoiding the prior authorization process. For example, demand for a medication (ex: GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic for weight loss) may be high enough with direct pay that there is little incentive to enter into lower negotiated list prices that require a prior authorization process. Alternatively, the incidence of a disease may be so low that maximum profit has to be extracted from each patient to offset the research, development and manufacturing costs, thus incentivizing the manufacturer not to enter into a lower negotiated rate with any contractor and ensuring that all patients who access the drug go through an insurance exemption request outside of typical prior authorization mechanisms. Ideally, pharmaceutical companies view prior authorization as a barrier and would prefer to have a free market without restrictions. As a result, pharmaceutical companies try to work within the existing system of PBM negotiations and prior authorization in order to maximize revenue and profits. This is particularly true in highly competitive markets or once a branded drug loses exclusivity and generic competitors enter the market. In these situations, prior authorization requirements from payors steer patients towards lower cost medications and ultimately drive price competition among pharmaceutical companies.

Providers: Physicians and other healthcare providers typically view prior authorization in a negative lens. For many, prior authorizations are viewed as an encroachment on autonomy that prevents practicing medicine as they would optimally desire.5 Providers also report feeling that guidelines for prior authorization, although published by payors, are inconsistent, difficult to access, and create an unethically difficult process for securing fair reimbursement. Unsurprisingly, an AMA survey reported that most physicians believe prior authorization negatively impacts patient care.6 Objective studies characterizing the burden of prior authorization on clinical workflows and patient care are limited; however, studies have shown that policies from insurance companies are sometimes not aligned with evidence-based medicine practices7, and that there can be significant variation in indications for the same service from payor to payor.4 Even more frustrating for providers, the medical directors at payors who make policy decisions and decide the fate of prior authorization requests allegedly have a higher track record of negligence and lawsuits while in clinical practice.8

Factors like this have been established to be contributors to clinician burnout given that it can feel like stakeholders with no direct patient care contact are dictating how care is provided, with no liability for reimbursement or how delays/denials of payment ultimately hurt patients. Beyond the issue of obtaining prior authorization, some providers have also highlighted other strategies that payors utilize to deny payment even after prior authorization is obtained successfully, though data showcasing the prevalence of this issue has not yet been published.9

It makes sense that physicians and other providers would like to have more control over these variables in patient care with less rigorous prior authorization processes. However, it deserves mentioning that although providers spend more time training to participate in the healthcare value chain than any other stakeholder, there has traditionally been an incentive to render as much care as possible under fee-for-service or volume-based reimbursement models. Indeed, some physicians have spoken out about how some rationing of resources is necessary to control cost, and other evidence points toward even the best trained physicians not being able to judge high yield care decisions.10 Furthermore, it is often difficult to access pricing information when making clinical decisions, which limits the ability to make cost-effective decisions, even if this is a salient concern providers are trying to address.

Hospitals / Care Facilities: Hospitals and healthcare facilities typically view prior authorization from a similar lens as providers. Prior authorization represents an obstacle to payment, and for a business model built on payment for services rendered, it is easy to see why prior authorization is frustrating. A professional with over four years of experience in the reimbursement department of a major corporate hospital system echoed these frustrations about difficulties in the prior authorization process.11 However, complaints focused more on the logistics of managing prior authorization and tracking reimbursement, not a principal problem with prior authorization itself. While some of the challenges may be attributed to internal processes which could be improved, a vast majority of the frustrations were due to objective complaints about the process of obtaining prior authorization from payors. Another practice administrator also reported similar sentiments, describing significant variation in the modality by which payors require prior authorization requests to be submitted, having no way to track prior authorization requests without submitting a payment request and having it denied, and trying to comply with strict technical criteria for when and where a service could be rendered if payment was to be provided after successful prior authorization. Long term care facilities brought the issue of prior authorization to a headline recently with reports about automated systems of prior authorization denial.12,13 All of these variables combine to create a dynamic where hospitals and care facilities stereotypically view the prior authorization process negatively.

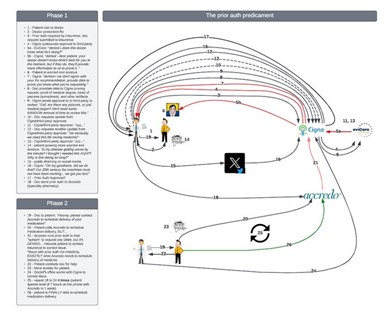

Patients: It is important to note that patients are the only other stakeholder, beyond payors, directly incentivized to reduce the cost of healthcare. The literature has provided evidence of this phenomena, where costs of care decreased by 11.8% – 13.8% when patients switched to a high-deductible plan.14 In cases where prior authorization protects patients from low-value care, patients may ultimately be appreciative of the role that prior authorization plays; however, it is difficult to convey this information. In cases where patients are unaware of prior authorization, or where it has no impact on their treatment regimen and timing, patients are likely indifferent to the prior authorization process. However, in cases where prior authorization results in delays in care, frustration typically abounds. This is easy to understand, given that patients almost always pay monthly premiums to a service they perceive does not provide the value it is supposed to deliver. Online reports from patients about the frustration with prior authorization are common, and a graphic showcasing a somewhat comedic, but not unrealistic, prior authorization process diagram highlights the complexity involved in modern day prior authorization (Figure 1).

Ultimately, failed prior authorization does not preclude a patient from obtaining services given that they could pay cash at the list price for anything insurance denies; however, the high cost of healthcare often makes this an unrealistic option. Debate is ongoing whether payors should inherit some legal responsibility for denied/delayed care given that premiums are paid specifically to be able to access care.15

Figure 1: Patient’s diagram showcasing their experience trying to navigate the prior authorization process to obtain a prescription. Replicated from the Twitter account of Dr. Mark Lewis.

Fact Check and Areas for Future Research

It is easy to understand the sometimes subjective and emotional arguments that stakeholders present for why prior authorization is viewed favorably, or unfavorably, from their perspective. However, to try to understand how prior authorization is truly impacting the field, objective data is needed. Summarized below are questions which aim to highlight the influence of prior authorization on healthcare, data that was uncovered during the course of this review to answer those questions, and areas for future academic study that would help to better characterize how current prior authorization processes impact healthcare delivery.

What percentage of prior authorizations are ultimately approved? 2021 Medicare Advantage prior authorization decisions were the only publicly available source located for analysis.16 In this report, 33.2 million out of 35.2 million (94%) of claims were approved on the first submission. Of the 2.0 million (6%) claims that were either partially or fully denied, only 212,000 (11%) were appealed. However, 173,000 of 212,000 (82%) appeals were successful. Thus, the net approval rate was ~ 33.5 million out of 35.2 million, meaning that 95.2% of prior authorization claims were ultimately approved.16 If so many claims are approved, it is easy to wonder if some of these prior authorizations are not necessary. However, details on the types of prior authorization requests that are approved and denied, as well as reasons for denial, are lacking. Furthermore, data characterizing prior authorization outcomes for commercial insurers was not located during this review. Detailed research to better demonstrate prior authorization outcomes would be beneficial to begin showcasing whether net savings from prior authorization offset the administrative expense of prior authorization management.

What percent of services require prior authorization? Each plan has different rules about which services require prior authorization, which may even vary on a regional level for things as simple as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis.17 In the sample of Medicare Advantage claims highlighted above, the number of prior authorization requests ranged from 0.3 million to 2.9 million per firm.16 This heterogeneity makes it challenging to characterize how many services require utilization of prior authorization versus how many services can be provided and reimbursed without prior authorization.

Although the exact proportion of services requiring prior authorization is difficult to quantify, one trend that has been reported is an increase in the number of services requiring prior authorization over time. Specifically, Medicare Part D prior authorization was required for ~24% of covered medications in 2019, up from only 8% of medications in 2007.18 This estimate about the number of medications requiring prior authorization is in line with estimates that in 2017, 25% of Medicare Part B claims would be subject to prior authorization requirements if serviced by a private insurer.19 While the precise number of claims requiring prior authorization is still only an estimate, prior authorization processes impact a notable portion of total healthcare expenditure. Future work characterizing the burden of prior authorization in different areas of healthcare (ex: medications vs procedures vs rehabilitation fees) would be beneficial.

Does prior authorization save the system money? The standard argument for prior authorization is that it saves insurers money.7 This is particularly true for step-tiered therapies where payors are able to direct patients to medications with better negotiated rates. However, a study examining mandatory referral to a physiatrist prior to spine surgery found that this change in the prior authorization process resulted in delays in surgery, increased net cost of care, and did not decrease the long-term incidence of spine surgery.20 Examples like this where prior authorization requirements increase the cost of care may be limited; however, if the initial intervention in a step-therapy is unsuccessful and was attempted only because of insurance requirements, net cost of care is potentially increased. The potential for increased cost with any prior authorization requirements should be carefully considered and not just assumed to be a net savings.

How much does the administrative burden of prior authorization cost annually? Providers and other stakeholders frequently complain about the burden of managing prior authorization requests. It is true that administrative tasks and expenses are a part of any business process. However, the exact degree to which prior authorization requests burden providers has been studied in only a limited fashion. A 2009 study estimated that outpatient physician practices spent between $23 billion and $31 billion a year on interactions with health insurance firms.1 Each physician may generate 45 prior authorizations per week, though this number may vary significantly by specialty and practice setting.6

Another study characterizing the burden of prior authorization requests in outpatient superficial vascular surgical procedures noted that most prior authorization denials were the result of improper documentation to meet payor standards. While the initial reaction to this may be that the provider should develop improved standards of documentation, this does not portray the full scenario. Cost-analysis revealed that the physician group spent over $110,000 on administrative expenses related to prior authorization during the study year, whereas the prior authorization denials were estimated to save payors less than $60,000. It is important to note that these cost estimates are only for a select subset of procedures and do not appear to reflect the total administrative cost for the practice.21

While studies characterizing the distribution of burden in navigating prior authorization are limited, this issue deserves particular attention. Each payor’s plan may only have one prior authorization process, but each healthcare provider typically serves patients with numerous different insurance plans. Because of this, the burden on the healthcare provider to navigate prior authorization processes is significantly greater than burden on a payor. Reform is needed to ensure equitable distribution of administrative burden across all stakeholders. Additional study should be directed at better quantifying the current administrative burden for providers and practice administrators versus payors in managing prior authorization requests.

How long does it take for providers to submit a prior authorization request? And how long does it take for a payor to make a prior authorization decision? Another potential point of disparity between providers and payors in administrative burden is the time required to submit and review a prior authorization request. Studies have cited prior authorization requests taking an average of 9.5 minutes / submission in urology22 to a median of 12 minutes / request in dermatology.23 Conversely, claim reviews have been reported to be as low as 1.2 seconds/review for insurers.3 While the disparity in time reported in these studies may overestimate the difference in time burden, there does appear to be evidence that on average, providers and their colleagues spend more time working on prior authorization requests than payors spend reviewing them. This is not inherently wrong; however, in cases of inappropriate denial, any perceived disparity in effort invested into the process may add to frustration. Additional research to better highlight the time required to manage prior authorization requests in relation to the total scope of business would be beneficial.

Who makes prior authorization determinations? The process payors utilize to make prior authorization review is not abundantly transparent and seems to vary on a case by case basis. NaviHealth, a product previously utilized by both Humana and UnitedHealth, utilized an AI algorithm (“nH Predict”) to determine whether patients qualified for long-term care after a hospitalization. A class action lawsuit is now underway against both companies for inappropriately denying care. Similarly, a class action lawsuit against Cigna is ongoing for its utilization of a tool dubbed “PXDX” which reportedly allowed for bulk denial of prior authorization requests without review. 2,3 Media reports have also described that a higher share of physicians participating in prior authorization review allegedly have worse track records in clinical care.8 Frustration also abounds when providers trained in a different specialty deny care. While reports of these stories are widespread, the objective study of how reviews occur has not been established and deserves further investigation.

How are prior authorization decisions communicated? There does not appear to be a uniform method for communicating prior authorization decisions. We uncovered less insight into the process of prior authorization for pharmaceuticals and step-tiered therapy. However, a professional with over four years of reimbursement experience reported frustration with the communication process for prior authorization decisions for surgical procedures. Frequently, the team member requesting prior authorization worked in close collaboration with the clinical care member. The person responsible for obtaining reimbursement was in a completely different department. This resulted in difficulty communicating the prior authorization approval; however, even when this communication occurred successfully, there were times when a denied prior authorization was only uncovered after submitting a claim for reimbursement. The reason for denial was not always included in this communication.11 Although the precise methods of communicating prior authorization decisions have not been uncovered, better transparency in tracking prior authorization decisions, and the rationale for denials, would seem to be beneficial.

Steps for Reform

Prior authorization is a topic that often solicits an emotional reaction. While some argue that a complete overhaul of the American system is needed, the goal of this review was to better understand the current landscape of prior authorization and elucidate realistic action steps that could be implemented to improve the experience for all stakeholders.

- Encourage collaborative work between healthcare stakeholders, including insurance companies and physicians. Legislative mandates can be passed to try and encourage positive change; however, change is typically more effective if direct stakeholders can be encouraged to “do the right thing” and make changes that are in everyone’s best interest without legal battles.15

- Develop a uniform electronic prior authorization process so that requests can be managed with less administrative burden. Under the current system, the variety of methodologies for managing prior authorization requests is extremely challenging. Some electronic prior authorization platforms are available, but not widely utilized in clinical practice.24 As a transition occurs to electronic authorization requests, it is important that the system doesn’t switch from every company having their own unique prior authorization paper form to their own unique prior authorization portal.25 To realize the full potential synergy and impact of an exclusively electronic prior authorization request system, centralized and common tracking requirements need to be established. While implementing a uniform electronic system may seem like a challenge, the pharmaceutical industry already made this transition from paper scripts into electronic prescriptions that are compatible across many different electronic medical records and pharmacies. This precedent should help drive change to develop a compatible and centralized methodology for tracking prior authorization requests. Data from other industries also supports that uniform information exchange processes improve efficiency.26

- While there are certainly examples of providers who abuse the system, the vast majority are judicious about providing care in line with established standards. Gold cards would serve as a method for payors to reward providers with a demonstrated track record of appropriate clinical decisions. For those providers with a gold card, the prior authorization process could be excluded or significantly more streamlined. Periodic review of cases after obtaining gold card status would ensure that providers don’t go unchecked. This option is particularly attractive because it incentivizes collaboration between two of the stakeholders who currently have with the highest amount of tension and has been endorsed by the AMA.27

- Many governing bodies in medicine invest considerable time into determining treatment algorithms based on the most up-to-date research studies. These care pathways are designed to maximize patient outcomes in a cost-effective manner. However, research studies have shown significant heterogeneity in coverage policies between different payors. Even worse, care policies are not easily accessible (or accessible at all) for some plans. For example, in a research study examining the criteria required to obtain a cervical MRI, only 66% of plans had publicly available clinical guidelines, and many of these guidelines did not follow American College of Radiology clinical appropriateness criteria.4 The full extent of discrepancy between payor guidelines and societal evidence-based recommendations has not been explored; however, this is a concerning trend. Developing a more consistent set of publicly available guidelines for care coverage would help to streamline prior authorization for many cases. For the limited set of cases that don’t fit neatly into guidelines, there should be more ample resources to go through a legitimate prior authorization process and consider unique reasons for why a different care pathway may make sense for that individual patient.

Ongoing Legislative / Government Initiatives

There are a variety of ongoing legislative initiatives designed to improve the process of prior authorization for all stakeholders. Some of these align with the recommendations presented above, while others represent different approaches for improving prior authorization processes. Summarized below are a few of the current national legislative initiatives, and one of North Carolina’s legislative initiatives. Similar state-level initiatives are ongoing in over 30 additional states.28

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Rule CMS-0057-F: Passed in January 2024, this mandate will require impacted healthcare plans (Medicare Advantage, state Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program Fee for Service, and some plans on the Federally Facilitated Exchanges) to transition to more expedient prior authorization reviews (< 72 hours) and electronically streamline the prior authorization process, along with more transparent information about prior authorization requirements (excluding drugs). Compliance with this requirement will not be fully mandated until January 1, 2027.29, 30

- HR 4968: Getting Over Lengthy Delays in Care as Required by Doctors (GOLD CARD) Act of 2023:31 Qualified physicians with a record of at least 90% approval rates in the prior year would be exempt from some prior authorization requirements in Medicare Advantage plans.

- HR 5213, Reducing Medically Unnecessary Delays in Care Act:32 Clinical criteria for which services are (or are not) covered by Medicare Advantage plans must be developed in collaboration with a qualifying physician who has an active medical practice in the specialty.

- 652, Safe Step Act33 and HR 2630, Safe Step Act:34 Step-therapy protocols exist to guide patients toward lower cost or higher margin services in the initial treatment steps. Payors would have to establish exemption processes for their step-therapy processes to allow for more rapid approval of services under several specified clinical conditions.

- NC HB 649:35,36, 37 This bill includes a variety of additional stipulations that would reshape the process of prior authorization in North Carolina, highlighted by key features summarized below:

-

- Clinical review based on nationally recognized medical standards.

- Flexible to allow for deviations from the standard care pathways when justified on an individual basis.

- Prior authorization denials only from physicians in that specialty.

- Patient must be notified if medical necessity is questioned by the payor.

- Payor must maintain a complete list of services where prior authorization is required.

- Shorter timeframe for prior authorization decisions, ranging from 60 minutes for emergency services to 48 hours for non-urgent services.

Conclusion

Prior authorization was initially developed as a check and balance to control cost. The evolution of healthcare business has morphed prior authorization into a complicated system that payors utilize for a variety of purposes, including steering patients towards lower cost and higher margin treatment options. While payors argue that all of this is undertaken with the goal of providing the highest quality care at the lowest possible price, other stakeholders such as providers, administrators, and patients report frustration that the barriers to navigating prior authorization processes serve as an unethical barrier to timely care and appropriate reimbursement. Anecdotal reports of frustrating care denials are abundant; however, limited studies have provided an objective assessment about the prevalence and impact such denials have on patient care. Regardless, most evidence suggests that the current process of obtaining and tracking prior authorizations has become inefficient.

Increasing frustration has prompted significant legislative scrutiny of the prior authorization process. Work is underway to refine the prior authorization process with new rules and regulations. A roadmap showcasing specific legislative initiatives and other improvement strategies is highlighted in this report, including recommendations for streamlined electronic prior authorization processes, gold card policies rewarding providers with an established track record of appropriate clinical decisions, and more standardized guidelines on indications for which care will and won’t be covered. Government interventions sound promising; however, without careful consideration during the implementation process, additional downstream consequences may occur. Ultimately, we believe improvement in prior authorization requires improved data characterizing the burden of current processes, increased transparency about how prior authorization decisions are made, and close collaboration between all stakeholders so that additional burdens are not inadvertently placed on healthcare providers and patients in an attempt to streamline the prior authorization process.

References

- Casalino LP, Nicholson S, Gans DN, et al. What does it cost physician practices to interact with health insurance plans? Health Aff Proj Hope. 2009;28(4):w533-543. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w533

- Minemyer P. Cigna hit with class action alleging it used an algorithm to reject claims. Fierce Healthcare. Published July 25, 2023. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/payers/cigna-hit-class-action-alleging-it-used-algorithm-reject-claims

- Cigna Sued Over Alleged Automated Patient Claims Denials. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/cigna-sued-over-alleged-automated-patient-claims-denials

- Berman D, Holtzman A, Sharfman Z, Tindel N. Comparison of Clinical Guidelines for Authorization of MRI in the Evaluation of Neck Pain and Cervical Radiculopathy in the United States. JAAOS – J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2023;31(2):64. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-22-00517

- Schwartz B. Post | LinkedIn. LinkedIn. Accessed November 27, 2023. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/ben-schwartz-md_health-healthcare-medicine-activity-7071638000006254594-vQwY/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop

- American Medical Assocation. AMA Prior Authorization (PA) Physician Survey.; 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/prior-authorization-survey.pdf

- Sharma SP, Russo A, Deering T, Fisher J, Lakkireddy D. Prior Authorization: Problems and Solutions. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6(6):747-750. doi:10.1016/j.jacep.2020.04.022

- Burke PR David Armstrong,Doris. Doctors With Histories of Big Malpractice Settlements Now Work for Insurers. ProPublica. Published December 15, 2023. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.propublica.org/article/malpractice-settlements-doctors-working-for-insurance-companies

- Tumialan L, Camarata P. It’s Not Brain Surgery – The AANS Practice and Business Management Podcast – Presented by the AANS on Apple Podcasts. Accessed October 25, 2023. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/denial-of-payment-after-successful-prior/id1628126631?i=1000626049047

- Episode 164: Scarcity in Neurosurgery. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://soundcloud.com/user-838542034/episode-164-scarcity-in-neurosurgery

- Miller J. Perspective on Prior Authorization from Experienced Professional with Over 4 Years Experience in the Reimbursement Department. Published online November 20, 2023.

- Pierson B, Pierson B. Lawsuit claims UnitedHealth AI wrongfully denies elderly extended care. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/legal/lawsuit-claims-unitedhealth-ai-wrongfully-denies-elderly-extended-care-2023-11-14/. Published November 14, 2023. Accessed December 19, 2023.

- Ross BH Casey. UnitedHealth discontinues a controversial brand amid scrutiny of algorithmic care denials. STAT. Published October 23, 2023. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.statnews.com/2023/10/23/unitedhealth-optum-navihealth-rebranding-algorithm/

- Brot-Goldberg ZC, Chandra A, Handel BR, Kolstad JT. What does a Deductible Do? The Impact of Cost-Sharing on Health Care Prices, Quantities, and Spending Dynamics*. Q J Econ. 2017;132(3):1261-1318. doi:10.1093/qje/qjx013

- Burgin J. NC Legislative Perspective on Prior Authorization. Published online December 4, 2023.

- Biniek JF, Published NS. Over 35 Million Prior Authorization Requests Were Submitted to Medicare Advantage Plans in 2021. KFF. Published February 2, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/over-35-million-prior-authorization-requests-were-submitted-to-medicare-advantage-plans-in-2021/

- Regional Disparities in Qualified Health Plans’ Prior Authorization Requirements for HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in the United States – PMC. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7272119/

- Resneck JS Jr. Refocusing Medication Prior Authorization on Its Intended Purpose. JAMA. 2020;323(8):703-704. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.21428

- Schwartz AL, Brennan TA, Verbrugge DJ, Newhouse JP. Measuring the Scope of Prior Authorization Policies: Applying Private Insurer Rules to Medicare Part B. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(5):e210859. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0859

- Goodman RM, Powell CC, Park P. The Impact of Commercial Health Plan Prior Authorization Programs on the Utilization of Services for Low Back Pain. Spine. 2016;41(9):810-815. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001329

- Lee V, Berland T, Jacobowitz G, et al. Prior authorization as a utilization management tool for elective superficial venous procedures results in high administrative cost and low efficacy in reducing utilization. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2020;8(3):383-389.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jvsv.2019.10.016

- Madhusoodanan V, Ramos L, Zucker IJ, Sathe A, Ramasamy R. Is Time Spent on Prior Authorizations Associated With Approval? J Nurse Pract JNP. 2023;19(2):104479. doi:10.1016/j.nurpra.2022.10.008

- Carlisle RP, Flint ND, Hopkins ZH, Eliason MJ, Duffin KC, Secrest AM. Administrative Burden and Costs of Prior Authorizations in a Dermatology Department. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(10):1074-1078. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1852

- Bhattacharjee S, Murcko AC, Fair MK, Warholak TL. Medication prior authorization from the providers perspective: A prospective observational study. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15(9):1138-1144. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.09.019

- Forys A. Review of Prior Authorization. Published online November 27, 2023.

- Cutler DM. Reducing Administrative Costs in U.S. Health Care.

- House bill advances “gold card” model on prior authorization. American Medical Association. Published August 30, 2023. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/prior-authorization/house-bill-advances-gold-card-model-prior-authorization

- Bills in 30 states show momentum to fix prior authorization. American Medical Association. Published May 10, 2023. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/prior-authorization/bills-30-states-show-momentum-fix-prior-authorization

- $15 billion win for physicians on prior authorization. American Medical Association. Published January 18, 2024. Accessed February 25, 2024. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/prior-authorization/15-billion-win-physicians-prior-authorization

- CMS Interoperability and Prior Authorization Final Rule CMS-0057-F | CMS. Accessed February 25, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cms-interoperability-and-prior-authorization-final-rule-cms-0057-f

- Rep. Burgess MC [R T 26. H.R.4968 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): GOLD CARD Act of 2023. Published July 28, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/4968

- Rep. Green ME [R T 7. H.R.5213 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Reducing Medically Unnecessary Delays in Care Act of 2023. Published August 15, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/5213

- Sen. Murkowski L [R A. S.652 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Safe Step Act. Published March 2, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/652

- Rep. Wenstrup BR [R O 2. H.R.2630 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Safe Step Act. Published April 13, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2630

- Aldridge R. NCMS Aided HB 649 Passes House Health Committee, Prior Authorization Bill Now heads to Rules Committee. North Carolina Medical Society. Published April 25, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://ncmedsoc.org/ncms-aided-hb-649-passes-house-health-committee-prior-authorization-bill-now-heads-to-rules-committee/

- House Bill 649 (2023-2024 Session) – North Carolina General Assembly. Accessed December 4, 2023. https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookUp/2023/H0649

- Ledger C. Her health insurer delayed her MRI – as the cancer spread. North Carolina Health News. Published May 8, 2023. Accessed December 4, 2023. http://www.northcarolinahealthnews.org/2023/05/08/health-insurance-prior-authorization-bill/