Aarthi Palaniappan, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania, and Herricks High School, New York, and Mark V. Pauly, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics and Department of Health Care Management, University of Pennsylvania

Contact: pauly@wharton.upenn.edu

Abstract

What is the message? This paper makes the argument that passage and implementation of price transparency legislation is motivated by demands from voters with high-deductible health plans (HDHPs). Consumers with these plans have the greatest perceived need for price information.

What is the evidence? In the time periods when states considered legislation (before the effective implementation of nationwide federal rules by 2022), we find a significantly larger percentage of workers with HDHPs in states that passed such legislation compared to those that took no action. This association suggests possible causation.

Timeline: Submitted: November 27, 2024; accepted after review, March 31, 2025

Cite as: Aarthi Palaniappan, Mark V. Pauly. 2025. Impacts of Price Transparency Legislation on High Deductible Health Plans: An Examination of Deductibles and Enrollment Rates. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.HMPI.org), Volume 10, Issue 1.

Introduction

Price transparency legislation has emerged as a critical tool in shaping the landscape of healthcare coverage; it has had bipartisan support based on the idea that better information about transaction prices between healthcare providers and insurers/consumers can, in some way, increase affordability and accessibility. On one hand, supporters and users of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) view price transparency as a crucial tool for consumers to shop for lower prices. On the other hand, consumer advocates view price transparency as a step toward greater fairness and influence over both price and quality.

Historically, there has been poor information available to insurers or consumers on the price that medical providers will require. Often the price is not known until after the service is rendered, and often the same service supplied by the same provider will have different prices for different buyers. This opacity is thought to be the reason why medical prices are “high” (since shopping for a lower price is difficult) and why sometimes consumers or insurers are surprised by prices higher than what they might have expected to pay.

The market for medical care is the antithesis of a typical commodity market in which prices are posted in advance and are uniform across buyers. The hope for price transparency is to have a buyer who knows the price or range of prices for a “shoppable” medical service that can determine the lowest price possible (presumably the lowest price the seller is willing to accept) and have an idea of what price would be charged by one seller compared to another(1). While knowing prices alone cannot guarantee a low-priced transaction, ignorance about prices can make it impossible.

The relationship of legislation to the prevalence of HDHPs is of particular interest, given the growing importance of HDHPs in the healthcare market and the argument that the consumer will have a strong incentive to search for lower priced sellers for a service whose cost will be under the deductible. For someone with insurance that has little or no cost sharing, there is no financial incentive to search for lower prices or better financial deals. But for those with high deductibles, there is a strong incentive, albeit one, the argument goes, that will work best if the consumer knows the range of prices in the local market for a given service. This study aims to investigate whether voters and their representatives are more likely to have passed price transparency legislation in states where more privately insured have insurance with higher deductibles. Consumers with low-deductible health insurance plans will not benefit from price transparency, but those who have chosen HDHPs require price information to make the best decisions. Previous literature has found that price transparency can lead to significant consumer savings for shoppable services if these services’ costs are below HDHP thresholds, indicating potential financial benefits for consumers from the reinforcement of price transparency in healthcare affordability. (2,3,4,5,6)

Building on the rationale that price transparency promotes competition, reduces information asymmetry, and empowers consumers, especially those with high-deductible plans, this research explores the potential implications of HDHP market shares for the passage of price transparency laws. The study looks at data from 2007, when the first state law was enacted, to 2022, when federal laws were passed and implemented in all states, to show how t

Federal Price Transparency Activities

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), or Obamacare, contained a provision requiring hospitals to post maximum list prices for a range of services (similar to the maximum room rates that were once required to be posted on motel doors). A rare example of effective bipartisan cooperation occurred in the early years of the Trump administration when Congress reached agreement on the need for further federal rules requiring hospitals to publicly disclose at least their list prices and eventually, the full set of negotiated prices from all payers. This process was slow; even after an executive order was signed by President Trump, final rules did not take effect until January 2021 and compliance by hospitals has been very slow, up to the present. Regulation has since been gradually extended from hospitals to health plans and, in some cases, net out-of-pocket payments (a combination of price and insurance provision information).

State Price Transparency Legislation

The time pattern of price transparency legislation can be divided into three phases. In the first (“pioneer”) phase extends from 2007, when New Hampshire first initiated legislation, through 2018, by which time a small number of states (12) had passed legislation. The evidence on effectiveness of these varying state plans was mixed(7), but bipartisan sentiment grew among states; impatient with implementation of modest federal legislation, six states passed state laws in the second phase, 2018 through 2020. From 2020 until the end of 2022, an additional nine states enacted complementary legislation. After compliance with stronger federal rules had taken effect nationwide, there was little additional state legislative action and the focus moved to federal efforts. We therefore show a comparison between states that passed price transparency laws in each of these three phased time periods. We relate passage in each time interval to the contemporaneous level proportion of group insurance taking the form of high- deductible health plans by state. We show the cumulative growth of state laws related to the HDHP proportion. We also discuss other possible influences on state legislation.

The Political Economy of Price Transparency

Opinions differ on both the desirability and the effectiveness of high deductibles on medical care spending and price shopping. HDHPs twinned with tax- shielded medical spending accounts of various types have for decades been a staple of Republican or market-oriented programs to contain healthcare costs. We hypothesize that voters have exogenously different preferences for this approach to health insurance and healthcare financing compared to other approaches such as managed care, which do not entail price shopping by insureds. Holding health risk constant, HDHPs will be favored by consumers willing to accept more financial risk, seeking to avoid managed care insurance restrictions on use, and eager to choose their own providers. The idea that HDHPs are “consumer-directed” health plans, where individuals decide what care from different hospitals or doctors is worth it rather than ceding that choice to an insurance administrator, is central to the ideology of HDHPs. It is also true that high-deductible plans are generally not attractive to people who are already at above-average risk of using healthcare. However, since the levels and distribution of health risk vary little across states, this is unlikely to affect the demand for HDHPs.

Our hypothesis is that in states with higher-than-average demand for HDHPs, voters will successfully push for price transparency legislation that facilitates rational decision-making under a high deductible. It is important to note that this hypothesis does not require people with HDHPs to actually engage in more price shopping than those with lower-deductible plans; it only requires that they believe they will and seek information to support that belief.

Method

Data on Plan Deductibles and Characteristics

The percentage of private-sector employees enrolled in high-deductible health insurance plans, per state, was collected from the State Health Access Data Assistance Center(8). Because the development and implementation of legislation takes time, we use three year averages centered on the year in question. Data on state passage of price transparency laws over the same period was obtained from the National Academy of State Health Policy Health Systems Tracker(9). The data on proportion of group insured workers with high deductible-plans comes from the same source

Measurement of State Legislative Actions

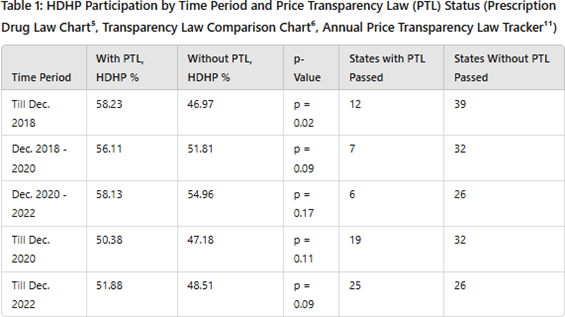

The dataset analyzed in Tables 1 and 2 used cutoffs to December 2018, December 2020, and December 2022. In addition, Tables 1 and 2 made use of the Annual Prescription Drug Price Transparency Tracker.(9,10, 11)

Statistical Analysis

By looking at data from the three periods described above, we tested the hypothesis that higher HDHP participation is associated with the higher likelihood of passage of state price transparency legislation. We compared average HDHP penetration per year in the 11 states that passed laws in the first period up to December 2018 with penetration in states that did not pass laws. In the second period, we compared, among the remaining 39 states, those that passed legislation during the period from December 2018 to December 2020 (calendar years 2019 and 2020) with those that did not. For the final two-year period, in which federal price transparency regulation became effective nationwide, we make a similar comparison.

Results

In Table 1, during the period before 2018, the percentage of group insured workers with HDHPs in “pioneer” states that passed price transparency legislation, was significantly higher compared to states that did not. While we cannot attribute causation to the HDHP proportion and while some states might have passed laws in any case, the results for the initial period are consistent with the hypothesis that an approximate 10% increase in private HDHP penetration was associated with 26% of the states passing legislation.

The first row of Table 1 shows that HDHP penetration was significantly higher in the “pioneer” states that passed laws compared to those that did not, with a statistical significance of 0.02. The next row shows the same qualitative difference in the second period with a significance of 0.09. In the last, less relevant period, there was still the same association of passage with high HDHP penetration, but now with a lower level of statistical significance. The importance of HDHP purchase thus was highest in the initial period but made less difference over time.

The last two rows of this table show the cumulative results for the two time periods (up to 2020 and up to 2022) with similar patterns, though with less statistical precision.

Discussion

These results suggest that there was bottom-up support for price transparency from consumer voters, who preferred the kinds of health insurance plans for which such legislation would make the largest difference. The complementary nature of high-cost sharing and better information to make choices using one’s own funds, is striking. Of course, supporting shoppable services is not the only reason to favor price transparency laws; they also help journalists to expose the complexities of the U.S. healthcare system and may assist some employers in determining which of their competitors are securing better deals from hospitals and doctors—so that they can try to secure them, too. In any case, further progress in improving pricing and reducing price discrimination in healthcare and health insurance can rely on citizens who prefer high-deductible plans for support.

Limitations

The associations shown here are not necessarily causal. The relationship between citizen preferences and collective actions in majoritarian representative states is obviously far from precise; there are many influences on political actions. The power of any study of state actions is limited by the maximum sample size of 51. It is possible that the spread of HDHPs was assisted by past or pending state price transparency legislation. In addition, the data on passage of legislation is only a rough measure of effective action, since both the timing of legislation and the timing of implementation can vary.

Conclusion

This analysis provides evidence that in states with higher levels of HDHPs, states were more likely to adopt price transparency laws before 2018. Actual evidence on how consumers with such coverage might use information mandated by law is scarce. More detailed information on what, if anything, consumers, employers, or insurers do with the additional information from such laws, still remains to be developed.

References

- Pauly, V., & Burns, L. R. (2020). When is medical care price transparency a good thing (and when isn’t it)? Transforming Health Care, 19, 75-97. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-823120200000019009\

- Emanuel, E. J., & Diana, A. (2021). Considering the future of price transparency initiatives – Information alone is not sufficient. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 4, Article e2137566. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37566

- Han, A., Lee, K., & Park, J. (2022). The impact of price transparency and competition on hospital costs: A research on all-payer claims databases. BMC Health Services Research, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08711-x

- Parente, S. T. (2023). Estimating the impact of new health price transparency policies. Inquiry: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing, 60. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580231155988

- Pollack, H. A. (2022). Necessity for and limitations of price transparency in American health care. American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, 24, Article e1069-1074. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2022.1069

- Zhang, X., Haviland, A. M., Mehrotra, A., & Huckfeldt, P. J. (2017). Does enrollment in high-deductible health plans encourage price shopping. Health Services Research, 53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12784

- Pauly, M.V., Rao, K., & Futoron, D. (2021). Light under a bushel: Medical price transparency regulation and low-priced seller behavior. Health Management, Policy and Innovation, 6. https://hmpi.org/2021/01/12/light-under-a-bushel-medical-price-transparency-regulation-and-low-priced-seller-behavior/

- State Health Compare. (n.d.). Percent of private-sector employees enrolled in high-deductible health insurance plans by total. State Health Compare. https://statehealthcompare.shadac.org/table/172/percent-of-privatesector-employees- enrolled-in-highdeductible-health-insurance-plans-by-total

- National Academy for State Health Policy. (n.d.). Prescription drug pricing transparency law comparison chart. National Academy for State Health Policy.https://nashp.org/state-tracker/prescription-drug-pricing-transparency-law-comparison-ch art/

- National Academy for State Health Policy. “Transparency Law Comparison Chart.” NASHP, https://nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Transparency-Law-Comparison-Chart-fina pdf.

- “2024 State Legislation to Lower Prescription Drug Costs – NASHP.” National Academy for State Health Policy, 3 September 2024,https://nashp.org/state-tracker/2024-state-legislation-to-lower-pharmaceutical-costs/