Elisha M. Friesema MBA, Stephen Palmquist, Prachi Bawaskar MS, MBA, Medical Industry Leadership Institute, Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota

Contact: Elisha M. Friesema, fries202@umn.edu

The 2018 BAHM Case Competition, held at the University of Miami School of Business, focused on business-based policy solutions to the national opioid crisis. Student teams from the University of Minnesota, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the University of Toronto took the top three places.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank their faculty advisors Drs. Archelle Georgiou and Mike Finch, the Medical Industry Leadership Institute at the Carlson School of Management, and the Minnesota Department of Health for their support.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abstract

What is the message?

What happens if a salmonella outbreak is suspected? Officials determine that this is not an isolated incident, then confirm it is salmonella making people ill, and detect the cause – most recently this was romaine lettuce. Hence, we find the point of origin and then control it by making sure its removed from all restaurants and store shelves to prevent more people from being exposed. This contagion model has also been successfully applied to social epidemics such as gun violence in Chicago.

This article discusses how to take these principles and reframe the way we think about and treat opioid use. Minnesota sees almost 400 opioid-related deaths each year. [1] There are concerted efforts underway to address the supply of opioids, both through provider prescription and drug seizures. Our solution, CEASE, attacks demand by bringing resources and support to those most at risk.

What is the evidence?

Review of analogous programs that have reduced gun violence in multiple cities.

Submitted: June 30, 2018. Accepted after review: July 31, 2018

Cite as: Elisha M. Friesema, Stephen Palmquist, Prachi Bawaskar. 2018. Community Empowerment to Address the Substance-Use Epidemic. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 3, Issue 2.

Background

Opioids have been in use for hundreds of years, but it was not until the 1990’s that pharmaceutical companies and patient advocacy groups began promoting their widespread use. In 2001, the Joint Commission declared pain to be the fifth vital sign, which some view as a trigger for providers to prescribe opioids more aggressively. [2] As excessive use built up, more potent opioids were sought out ultimately leading to the declaration by President Trump that the opioid epidemic is a public health emergency. [3]

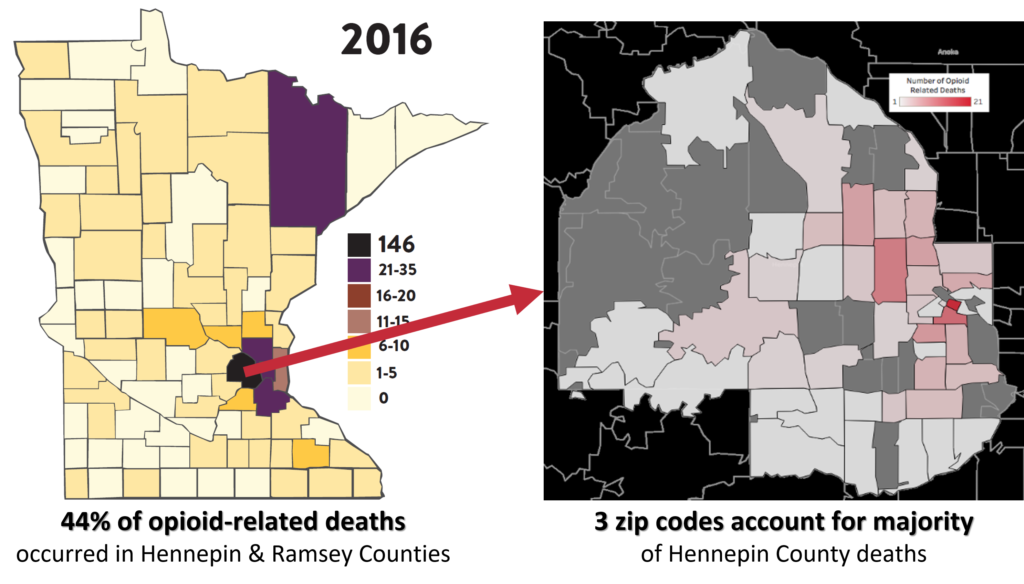

Within Minnesota most opioid-related deaths are centered in a handful of counties. Prescription opioids are more likely to be used by 45- to 54-year-olds whereas 25- to 34-year-olds are more likely to use heroin. [1] As heroin use continues to rise, we anticipate the average age of death to decrease. We chose to focus on Hennepin and Ramsey counties, which are home to the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, which represent 44% of Minnesota’s deaths.

Profile and Risk Factors for Opioid Dependence

Risk factors for the development of a substance use disorder accumulate over a lifetime and range from genetics, substance exposure during pregnancy, adverse childhood events during infancy and early childhood development, early exposure to drugs, and drug-usage in social contexts during high school. Additional factors are directly related to social determinants of health and include a lack of a livable wage, safe housing, quality education, health insurance coverage, social support, and social cohesion. [4]

Numerous studies have examined the epidemiology of substance use disorders to understand the factors driving initiation of opioid use. Research repeatedly shows that social and familial networks containing an illicit drug user are the strongest single predictor of illegal drug use in an individual. [5] Consequently, substance use bears similarities to a contagious disease; moving from contact to contact, illicit drug use spreads through social and familial networks ensnaring people and their communities. Thus, preventing a person’s first exposure to prescription opioids can significantly decrease their likelihood of becoming addicted in the future.

After initiation, it is essential to understand the risk factors that lead to an overdose. The main known risk factors include: high dose of prescription opioids (over 50 morphine milligram equivalents), using benzodiazepines or alcohol concurrently with opioids, taking long-acting opioids, using prescription opioids that are not prescribed to the user, using opioids after a period of sobriety, using heroin, fentanyl, synthetic opioids, or having a previous non-fatal opioid overdose. [6]

Continued use is another concern as it can lead to physical dependence and often results in loss of employment, insomnia, troubled relationships, societal isolation, depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts. [7] These factors echo those identified in the social determinants model that influence why an individual may start using opioids in the first place, suggesting that a substance use disorder can send an individual into a spiral of use from which it becomes increasingly difficult to recover.

Supply

Opioids reach consumers through several mechanisms. An individual can receive a legal prescription from a medical practitioner and fill it at a pharmacy. Legally prescribed pills can also be given or stolen by friends or family members or sold illegally “on the street.”

Illegal opioids have multiple channels. Heroin flows into Minnesota from Mexico up Interstate 35. Fentanyl and fentanyl synthetics are often manufactured in China and shipped through Canada into the United States via the mail service. [8] This is particularly problematic as fentanyl is not currently detectable by traditional screening methods and is easy to obtain. It took our team less than two minutes before we were entering credit card information into a website guaranteeing delivery of hydrocodone to our office.

Current Efforts to Curb Supply

There are significant efforts by both the federal and state governments to curb the supply of opioids. Law enforcement focuses on seizures and arrests, while public health officials emphasize campaigns such as drug-take back days and drop boxes. In a local effort, Hennepin county committed to having every first responder carry Naloxone.

Providers and health systems have also made dramatic efforts to curb inappropriate prescribing across the country and are implementing quality improvement efforts including benchmarking and peer comparisons. Minnesota providers have driven their rates down almost 10% annually. [4] Providers are required to register for prescription monitoring programs, but not yet required to monitor lists prior to prescribing.

Efforts to re-educate and train providers are also underway. These mostly target dentists, who are the largest class of inappropriate opioid prescribers. Along those lines, there are efforts to decrease first time prescribing. We know that the earlier a person is exposed to opioids, the more likely they are to have a substance use disorder in the future.

What Are the Gaps in Minnesota?

It is clear that Minnesota is tackling many aspects of the opioid crisis, but there are significant gaps in the current approach. Most significantly, weaknesses exist in:

- Reactive: Waiting for the individual to either seek treatment on their own or have a medical emergency requiring intervention rather than proactively seeking them out

- Uncoordinated: Lack of coordination between community entities to connect an individual with the resources they need despite willingness to work collaboratively across sectors

- Individual-centered: A lack of concerted effort to stop the spread of drug use through social and family networks

Proposed Solution

Fortunately, there is a proven approach that empowers communities to solve complex issues that span medical, social, economic, and cultural realms. An adaptation of epidemiologist’s Contagion Model, under the name ‘The Cure Violence Model,’ has been successfully implemented to address gun violence in cities across the country over the past decade, many of which make the news every day, including Baltimore, New York, and Chicago. The contagion approach helps isolate, contain, and resolve conflicts that lead to gun violence. Independent evaluations show a 41% to 73% decrease in shootings and killings in targeted neighborhoods. Critically, 95% of parents who interacted with Cure Violence reported it making them better parents indicating a ripple effect on the entire community, influencing beyond the primary target of gun violence [9]. By adapting this approach, CEASE can act as a convener for the existing resources for individuals and families and address demand for opioids.

Cure Violence Model

The Cure Violence Model uses the core principles of curing infectious diseases to address the problem of gun violence. Instead of using a law enforcement-based approach, the model addresses the social issues that significantly contribute to violent behavior. [10] The Cure Violence team identifies at-risk individuals and provides resources at both the individual and community level for identifying ways to resolve conflicts.

Cure Violence uses a three-step approach to prevent violent crime by 1) impeding the spread of violent behavior, 2) diagnosing and changing mindset of potential at-risk individuals, and 3) providing alternate solutions to violent crime. [10] The model’s success is attributed to four features.

- Works independently of law enforcement without impeding their work

- Addresses root causes of violence

- Collaborates with existing community resources and structures

- Empowers the community by focusing on hiring community members in pivotal roles

The focal points of the model involve identifying at risk groups, tracking violent acts in the community, and quickly deploying “Violence Interrupters”, who are hired staff from the community, trained to diffuse situations and help at-risk individuals find the resources they need. Many Violence Interrupters have a personal history with violent crime, including being former gang members; they are now critical leaders in the community.[11]

The CEASE Model

The CEASE (Community Empowerment to Address the Substance-use Epidemic) model focuses on individuals who are currently addicted, those in remission, and those who are at risk for future use. With this, we detect the hotspots and dedicate resources to them to isolate and treat those in need. We then engage the community to ensure the epidemic it does not spread.

Establishing Hubs

Applying the foundational principles used in the Cure Violence Model, community offices, or “hubs,” will be established within neighborhoods to address the different social determinants of health for the identified group. Data feeds from multiple sources will identify the areas at highest risk in real time so that community hubs can be established to isolate opioid misuse. A Data Analyst will work with the coroner’s office and law enforcement to build a real-time heat map and demographic database containing drug overdose deaths, overdoses, and arrests. This will provide the organization the ability to flex resources quickly to respond to community needs. 2016 death data from Minnesota Department of Health and Hennepin County Coroner’s office show that only a handful of zip codes are contributing to the high number of deaths seen in Hennepin County (Figure 1). With a full time data analyst and strong community connections to law enforcement, medical entities, and the coroner’s office, future data can pinpoint exact addresses of overdoses, deaths, and opioid related arrests. This data will allow for specific placement of CEASE hubs.

Community workers will work to identify individuals and provide crisis intervention when someone is at risk for relapse or just had an overdose. They will meet those at highest risk where they are, rather than waiting for them to come to CEASE, and will connect them with existing community resources to address their social determinants of health. The hub will act as a center for the entire community, raising awareness, creating a support center, and ultimately decreasing the stigma often attached to opioid-use-disorders.

Key Activities

Safe and healthy communities develop by changing behavior and disrupting the status quo. Key activities engage high-risk individuals, teach coping skills to avoid opioid use, and enable access to resources. Community outreach programs, advertising, events, collaboration with community groups, and positive law enforcement relations will increase awareness and empower communities to change in the status quo. These activities will result in outcomes that decrease socioeconomic stressors and allow participants to avoid opioids, overcome stereotypes and become productive members of their community.

As discussed earlier, CEASE will connect individuals with community services as needed using a hub-and-spoke model with the individual in need at the center and a CEASE employee by their side. Together they will evaluate the individual’s need for specific services “spokes” to reduce stressors that affect substance users and allow them to drive the needed change in their lives. The eight individual spokes of community services include transportation, food, housing, education, job training, employment resources, medical care and mental health, and combating social isolation.

The face of CEASE, and the critical factor that differentiates it from current efforts to address the opioid epidemic, are the Community CEASE Workers. Many individuals who are in this role have a history of substance use disorder and live in the community, so that they can be accessible – physically and emotionally – to the individuals in the community. This background and experience will help establish trust and position CEASE as a safe space to seek help.

The Community CEASE Workers will be trained on motivational interviewing and cessation discussion strategies. They will be knowledgeable in ascertaining clients’ needs and in connecting them to available community resources. CEASE workers will also work preventively with families and friends of individuals battling this disease, to ensure strong support networks and inhibit the contagious spread of substance use. Additionally, these community resource workers will raise awareness and create collaborative coalitions with existing community entities to better combat the opioid epidemic.

The hub will also house a group of nurse practitioners and medical assistants trained in treating chemical dependency. To establish the highest level of trust and minimize as many barriers as possible, these medical teams will work in the hubs and connect with specialized medical facilities as needed.

The greatest strength of our model is the capacity to flex services depending on the particular needs of the community and each individual:

Example 1:

- Maria Smith: High functioning executive, mother of 2; in remission for 16 weeks

- Crisis: Recently lost her job as a CFO

- Intervention: The team will help address employment and social support. Within the social network, we will isolate anyone who is currently using or also at high risk. Next, we will address his immediate needs. Maria needs to feel like she is not alone in this. She needs a new job, to have income to keep a roof over her daughters’ heads and food on the table. CEASE will address the root causes and stressors that could drive her to relapse.

Example 2:

- Joe St. Paul: Current heroin user

- Crisis: Has just been admitted to a local ER for a heroin overdose, has been arrested in the past for possession of illicit drugs, is sleeping at friends’ houses, and has not been regularly employed in over a year

- Intervention: Because of CEASE’s relationship with the hospital, they notified us so we could seek him out. CEASE engaged his existing support network and identified anyone at risk of hindering his recovery. Given Joe’s situation, he needs assistance in almost every area so we bring in a team to help.

- An advanced practice nurse helps address his medical needs, getting him started on MAT.

- A social worker helps to get him into a local long-term shelter to provide a safer more stable environment as well as consistent meals.

- Our case manager checks in with him daily just to see how he’s doing and to remind him we are there for him and that there are group sessions being held several times that day and we hope to see him at one.

- Once Joe has reached remission, the team will begin to address other areas, like employment, education, and consistent transportation.

Organization Structure

CEASE will be a formally organized as a 501(c)3 non-profit organization with the following vision and mission:

Vision: CEASE will free individuals, families, and communities from the harms inflicted by substance use disorder.

The three strategic themes within this vision are to:

- Reduce the number of deaths caused by substance use

- Reduce the number of individuals suffering from substance use disorders through prevention of initiation and cessation.

- Create a sustainable, scalable, and replicable community empowerment model to address substance use across the Twin Cities that could be adapted for other sites

The organization will have a traditional non-profit structure with a Board of Directors, which will provide strategic direction and oversight, and a management team responsible for operational execution. The board will be comprised of a diverse group of key stakeholders and key opinion leaders from different sectors of the community.

Key staff will include:

- Chief Executive Officer

- Communications and Marketing Director

- Operations Director

- Data Analysist

- Business Development Director

- Human Resources Director

- Finance Director

Under the direction of the operations director, each hub will employ:

- Community Service Manager

- Community CEASE Workers

- Case Coordinators and Social Workers

- Nurse Practitioner

- Medical Assistants

Stakeholder Commitments

This success of the CEASE model requires buy-in, cooperation, and integration with multiple stakeholders. Engagement with the Minnesota Department of Health is a first step as it will act as a crucial partner organization. The Department’s existing relationships with county social services organizations will provide foundational support for CEASE.

Subsequently, other organizations will be engaged to provide the resources necessary to provide each of the model’s spokes. Initially, these will include: Hennepin Health, Fairview Health, Metro Transit, Aeon, Catholic Charities, MN Career Pathways, HIRED, Avivo, Lutheran Social Services, Second Harvest Heartland, Minnesota and St. Paul Sheriff’s offices, Tubman, and Hazelden Betty Ford Drug and Alcohol Addiction Programs. These organizations provide vital services in each of the spokes and are trusted and respected resources in the community. Creating a centralized resource for at-risk populations will increase access and reduce frustrations in an already resource-poor environment.

Implementation and Tracking Success

To ensure operational efficiency, CEASE will be implemented through a phased approach. Phase 1 will consist of a single pilot hub in one of the hardest hit zip codes in Hennepin County (55403). Through this, CEASE will learn from and continuously improve upon our model and practices, before scaling up to serve our entire target community. Phase 2 will expand to a total of 10 hubs across Hennepin and Ramsey counties. Phase 3 will further extend beyond our community to 25 hubs across the country.

Determining the effectiveness of the CEASE model will involve several evaluation metrics. The primary outcome will be the number of opioid-related deaths in Hennepin and Ramsey counties. Secondary measures will include the number of emergency department visits for opioid overdose in Hennepin and Ramsey counties, the number of arrests by law enforcement for opioid possession, and utilization and satisfaction rates of CEASE community hubs.

Program Cost

The estimated CEASE’s annual program cost for phase 2 is approximately $13 million. We arrived at this estimate by using median salary information for each desired position from the Bureau of Labor Statistics or non-profit survey data, adding overhead costs per employee, and estimating the number of staff needed to support our model. We assumed ten community hubs will be needed across the Twin Cities area based on heat map data. To estimate office and overhead costs we found a median cost of renting commercial space in Minneapolis to be $22 per square foot. Based on the number of community workers needed to implement the Cure Violence model in several large cities across the United States [12], we estimate the need for 80 community CEASE workers. Additionally, Cure Violence estimates that the average cost of implementing their model ranges from $10 to $13.3 million, further justifying our cost estimate. [13]

Funding

Due to the length of time and complicated process needed to secure government funds for a project of this magnitude, we recommend three approaches to obtain the necessary funds. Each method can independently fund this community intervention.

Federal funding: Our first target would be grants from the money allocated by the Trump Administration to combat the opioid crisis. Next year alone, the Trump Administration has requested $625M in funding to be given out to states and we propose receiving the necessary $44M to run our program for a minimum of 4 years. [14]

“Penny-a-Pill” Fee: A new stream of state-level revenue from a one-cent stewardship fee on every morphine milligram equivalent of opioids dispensed in Minnesota. While this revenue stream would be an entirely new source of funds, the one-cent fee has broad support in Minnesota and has been endorsed by the governor and state legislators. [15] State government analysis shows that this revenue stream would generate $20 million a year. [12] Our organization would apply for funding from this revenue stream.

Extension of the expiring Minnesota provider tax: Our third revenue stream recommends the continuation of an existing medical tax that is set to expire. Since 1991, Minnesota has had a 2% tax on providers, levied explicitly on the revenues of hospitals, providers, pharmacies, and wholesale drug distributors. This tax has historically funded expanded medical insurance for low-income citizens. In recent years, the funding of expanded medical coverage has shifted towards general taxation, making the sun-setting of this tax more feasible. Currently, this tax raises $700 million a year and is set to expire in 2020.[16] Even if the tax is reduced to 1%, we would still be asking for less than 10% of the revenue. Much like the one-cent fee on opioid pills, this law would require action by government bodies to extend an existing tax, which may be difficult and require interim ways to fund the program. Additionally, both provide a way for those who are partially responsible for creating this epidemic to directly contribute to its solution.

Impact Analysis

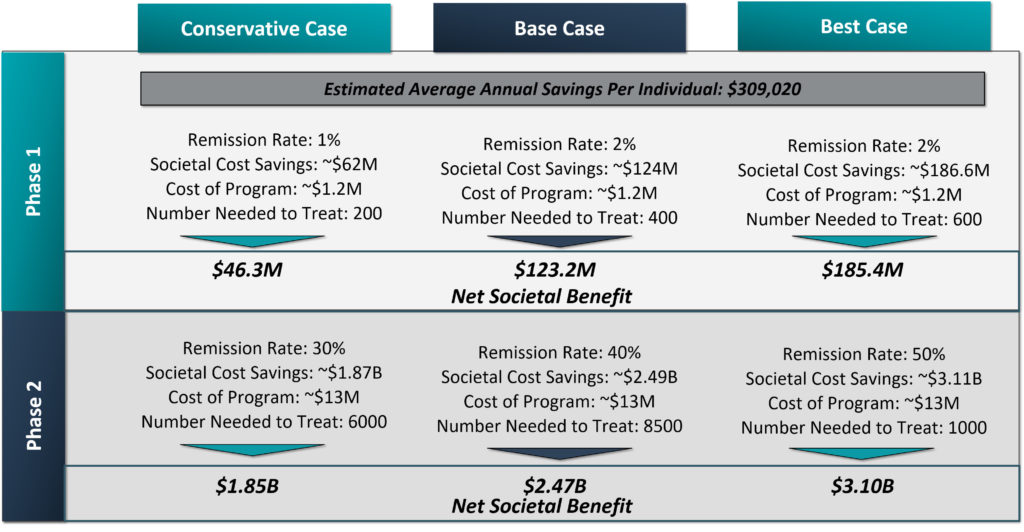

To evaluate the societal economic impact of our community intervention we created a break-even cost and a projected impact model. To value the impact of treating an individual we have used the estimated cost to society of an individual with opioid use disorder as used by the Minnesota Management and Budget, which is $309,020 per year. [17] The break-even point for phase 2 occurs through assisting 42 individuals into remission. Beyond that, we would have a societal surplus.

Looking at estimates of what is achievable given the success of the Cure Violence model in cities across the globe, the lowest results seen in any particular city, after full implementation, is a 41% drop in shootings and killings. [9] Using this as a target value, we estimated the net impact of our program if we could achieve a 30, 40, or 50% decrease in the number of opioid addicted individuals in our target community (Figure 2). Of note, the number of opioid dependent individuals in our target community is unknown, but survey data has shown that for every person who dies from a drug overdose, there are 115 people abusing opioids in the community [18]. Using this methodology, we estimate the value of this program to our community could exceed $2 billion.

Conclusion

Spreading like an infectious disease through our country, the opioid epidemic is ravaging communities across the U.S. In Minnesota’s Hennepin and Ramsey counties alone there were 175 opioid overdose deaths in 2016 — that number is expected to rise. Geocoding analysis, along with the epidemiological research, reinforces our conclusion that substance use disorder spreads through family and social networks, much like a public health epidemic. From our review of community resources and community initiatives, there are definite plans to address many aspects of the opioid epidemic. The significant gap within this community remains a lack of coordinated resources to attack the root causes of why an individual begins using and does not quit.

CEASE addresses the root causes of substance use by empowering the community to identify those at risk and get them the resources they need. With the societal and political desire to solve this critical issue, we believe that CEASE would get the funding it needs, especially given its potential cost savings to society. Furthermore, after full implementation, our community intervention has the ability to scale to communities across the country.

References

- Wright, N., Roesler J. Drug Overdose Deaths among Minnesota Residents 2000-2016. Minnesota Department of Health Injury and Violence Prevention Section: Minnesota Department of Health;August 2017.

- Baker DW.The Joint Commission’s Pain Standards: Origins and Evolution. The Joint Commission;2017.

- President Donald J. Trump Is Taking Action on Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. In: House TW, edOctober 26, 2017.

- Indicator Dashboards Opioid Dashboard. The Minnesota Department of Health. www.health.state.mn.us/divs/healthimprovement/opioid-dashboard/#NumberPrescriptions. Published 2018. Accessed March 11, 2018.

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The social epidemiology of substance use. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:36-52.

- Prevention & Control Opioid Overdose. Minnesota Department of Health. www.health.state.mn.us/divs/healthimprovement/health-information/prevention/opioid.html. Accessed March 11, 2018.

- Bennett M. The Great USA Opioid Epidemic with Expert Insight. In. ConsumerProtect.com2017.

- Scott D. This Is How Easy It Is to Order Deadly Opioids over the Internet. In. Vox: Vox Media; 2018.

- Cure Violence. Scientific Evaluations. Cure Violence. http://cureviolence.org/results/scientific-evaluations/. Accessed March 11, 2018.

- Butts JA, Roman CG, Bostwick L, Porter JR. Cure violence: a public health model to reduce gun violence. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:39-53.

- Cure Violence. Annual Report 2014. Cure Violence;2014.

- Butts J. Evaluating the Cure Violence Model in New York City. John Jay Research and Evaluation Center;2016.

- Cure Violence Admin. Policies to Cure Violence. In. News & Events. Vol 2018: Cure Violence; 2013.

- An American Budget, Fiscal Year 2019. In: House TW, ed. www.whitehouse.gov2018.

- A ‘Penny-a-Pill’ to Fund Opioid Treatment and Prevention. In: Office of Governor Mark Dayton SoM, ed: Office of Governor Mark Dayton; 2018.

- Carlson HJ. Bill Would Keep Medical Provider Tax in Effect. In. The Post Bulletin. PostBulletin.com2016.

- Merrick W, Elder T, Bernardy P. Adult and Youth Substance Use Benefit-Cost Analysis. mn.gov: Minnesota Management and Budget;2017.

- Registration Support. DEA Diversion Control Division. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/. Published 2018. Accessed March 11, 2018.