Markus Saba, Kati Schy, and Daniella Kapural, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Contact: Markus_Saba@kenan-flagler.unc.edu

Abstract

What is the message? The evidence concerning high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) suggests three key patterns involving people with diabetes (PWD): (1) a disproportionately negative impact on low-income individuals; (2) low healthcare literacy as a predictor of poor health outcomes; (3) the influence of insurance design on consumer and health behavior. The patterns suggest that HDHPs can be customized to the diabetes disease state in order to reduce cost and improve health outcomes. Changes include policy advances, special initiatives for PWD, and leadership by employers.

What is the evidence? The conclusions are based on an extensive literature review plus deliberations of an expert panel.

Link to white paper: https://cboh.unc.edu/index.php/ki-research/?researchID=11208

Timeline: Submitted: June 2, 2020; accepted after revisions: June 16, 2020

Cite as: Markus Saba, Kati Schy, and Daniella Kapural. 2020. Assessing the impact of high deductible health plans on people with diabetes. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI.org), volume 5, Issue 2, June 2020.

Many People with Diabetes Have High-Deductible Health Plans

Since the introduction of high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) to the U.S. in 2004, there has been much ambiguity surrounding how HDHPs affect access, costs, and outcomes of health care. This topic is especially relevant to patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, who have more frequent health-monitoring demands. Understanding the net impact of HDHPs on people with diabetes (PWD) will determine what changes and improvements to HDHPs should be implemented.

HDHPs are defined as a plan with a deductible of at least $1,300 for an individual or $2,600 for a family1. The intent behind HDHPs is to reduce overall healthcare costs and utilization by incentivizing individuals to be more conscious of unnecessary medical expenses, while making healthcare coverage more affordable as a result of lower insurance premiums.

While HDHPs can be beneficial under certain circumstances, the impact of HDHPs on PWD is uncertain. HDHPs may have negative health and financial consequences for people with chronic illnesses such as diabetes because the out-of-pockets costs are high and continue over time. This is particularly relevant for PWD as this group of patients is growing, costs are increasing, improved outcomes take time, and complications emerge over time. People with chronic conditions on HDHPs may end up deferring necessary healthcare which can result in poor outcomes and higher costs in the long run2,3.

The analysis explores how healthcare costs change under different circumstances, whether health outcomes for PWD are better or worse with HDHPs, and if there are other implications and patient behaviors that should be taken into consideration.

Research Design

The research project included three phases.

Phase I: Literature Review – Review of thirty-nine studies from reputable medical journals and other scholarly publications. Seven of these studies focused specifically on HDHPs and PWD.

Phase II: Advisory Board – We facilitated a roundtable discussion held on February 12, 2020 with eight leading experts in the diabetes field representing multiple perspectives.

Phase III: White Paper – A detailed report captured the output, conclusions, and recommendations of the literature review, data analysis, and advisory board.

Literature Review: Three Themes

Thirty-nine research publications were selected based on inclusion of studies on the association of HDHPs and outcomes in PWD. Thirteen of the initial studies were selected from the honors thesis of Pooja Joshi, a UNC student who partnered with UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School’s Center for the Business of Health (CBOH) in 2018 to explore trends in diabetes care and HDHPs. Of the thirty-nine, seven publications focused on PWD, five focused on chronic illnesses and mentioned diabetes, and the other twenty-seven focused on the broader scope of health in the context of HDHPs and healthcare costs.

The relationship between HDHPs and health outcomes is complex. While most studies found an association between HDHPs and negative health outcomes for PWD, some studies found no difference. Some variables overlapped so that HDHPs were associated with one variable (e.g., decreased healthcare utilization), but showed no statistical association with another variable (e.g., health outcomes).

Despite the complexity, three themes emerged from the literature review, concerning income disparity, health insurance literacy, and consumer and health behavior.

Income Disparity

Although previous literature suggest that HDHPs may result in cost savings from reduced healthcare utilization, much of the research analyzed in this review suggests that lower-income individuals may be adversely affected by the HDHP insurance design. Health care and maintenance costs for PWD are substantial, even for patients who are insured4,5. The literature demonstrates that HDHPs do decrease utilization among PWD6; however, the lower utilization may result in severe medical consequences for low-income subgroups3,7.

Compared to families enrolled in traditional plans, families whose members have chronic conditions commonly reported financial burden related to healthcare costs, especially when enrolled in HDHPs8; this number doubled for low-income families in HDHPs9. Although HDHPs offer lower premiums, they generally result in higher out-of-pocket expenses when medical events occur. For chronic diseases such as diabetes, higher numbers of medical events are nearly certain to occur, driving out-of-pocket expenses up for PWD.

Uninsured PWD are predominantly from low-income households or belong to a minority group, and receive less preventive care than insured PWD10. Even for the insured population, though, lower income has substantial relationships with HDHPs and inferior outcomes.

Low-income PWD who are insured privately — and have high deductibles – are more likely to report forgoing needed medical services, such as outpatient visits or diabetes management medications11,12,13. Forgoing primary or preventive medical treatment puts these patients at risk for higher severity emergency department (ED) visits and poor health outcomes in the long-term. Studies showed that after an employer-mandated switch to HDHPs, low-income patients experienced concerning increases in high-severity ED visit expenditures and hospitalization days14,15,16.

Health Insurance Literacy

Health insurance literacy is the degree to which patients have the ability to access and understand information about health insurance plans, select the most appropriate plan for their circumstances, and utilize the plan effectively to maintain good health. While only a few studies focused specifically on health insurance literacy, the relevant research reflected that many patients were unsure or uninformed about their health insurance plan and its benefits.

Our research validated the importance of health insurance literacy in optimal healthcare utilization. One study evaluated comprehension of insurance plans and plan choice separately. This 2013 study showed that only 14 percent of Americans correctly identify the four basic components of health insurance plans: deductible, copays, coinsurance, and maximum out-of-pocket costs and only 11% of Americans adequately understood the cost of hospitalizations17.

It appears that consumers do not understand their current insurance plans, and studies suggest that plan simplification could be beneficial to the optimization of HDHPs17,18. Another study found that consumers “frequently reported changing their care-seeking behavior” due to cost, despite having limited knowledge about their deductibles18.

While HDHPs were designed to reduce overall utilization, poor health insurance literacy limits the intended effects of deductibles and adversely impacts health outcomes for patients with chronic illnesses19. Across the studies, three attributed unused benefits to poor health insurance literacy. A 2017 study of low-income PWD, for instance, found that patients enrolled in HDHPs might experience increased severe health outcomes by forgoing primary care that is covered by their plans3. Another study found patients enrolled in HDHPs are likely to reduce preventive care use, even when covered without cost-sharing, and they are largely unaware of the fact that preventive care is free or low cost1.

Three studies elaborated on how the limitations of insurance markets (e.g., adverse selection) and inadequate health plan choices by consumers can lead to negative health outcomes for patients20,21,22. Better patient awareness and decision support is a key aspect of optimizing plan usage and helping consumers understand their insurance benefits (e.g., making a distinction between when care is necessary, unnecessary, or discretionary)18. When provided the resources, consumers seem to utilize health and cost information to make their decisions23.

Consumer and Health Behavior

The majority of the research reported broadly on consumer and health behaviors—how patients prioritize or maintain their health depending on their healthcare plan. As HDHPs were designed to do, they shape the patients’ consumer behavior. However, these changes in consumer behavior also translate to changes in health behavior.

Our research demonstrates that these changes can have damaging health effects on people with chronic illnesses such as PWD. Additionally, health and consumer behavior are interconnected. For example, consumers’ health status plays a key role in their consumer behavior, specifically their choice of plan; the probability of choosing high-premium health plans increases with more chronic comorbidities among family members24.

Consumer Behavior

Consumer behavior is a patient’s responses to the design of the insurance plan and how such behaviors impacted the utilization of healthcare services. Among the studies, topics ranged from consumer elasticity in healthcare to moral hazard to attitudes about preventative care. It appears that higher deductibles significantly decrease opportunities for early detection, management, and care coordination of chronic diseases25,26.

Four publications focused on the need for competition in healthcare to change patient behaviors27,28,29,30. Some of the recommendations included putting patients at the center of care, creating choice, and standardizing value-based methods of payment31. Others explored solutions related to bundled payments or value-based insurance designs32. Another publication focused on providing financial incentives to patients with diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol, to better manage their health33. However, one study showed that switching to an HDHP did not change medication availability or reduce use of essential medications34.

Health Behavior

Health behaviors are actions people take to maintain or enhance their health, or prevent disease. Diabetes is largely a behavioral disease, as it can be improved, managed, or prevented with good health behaviors. Good health behaviors such a healthy diet, regular exercise, and adherence to medical regimens (e.g., monitoring insulin) are critical components of diabetes management.

Studies found that patients under insurance plans with less coverage show a lower likelihood of exercising regularly, modifying their diet, and using oral medication for chronic illnesses9,35. Another study found that insurance type had a significant effect in determining which insulin management plan patients followed, showing increased use of insulin pumps, and lower HbA1cs among privately insured patients36. Similarly, it is generally shown that those enrolled in HDHP with chronic conditions such as diabetes adhere five percent less to their prescribed medication than those that did not switch plans37.

The research suggests that costs associated with high deductibles provide a financial incentive for families to make certain sacrifices to their health. Delayed and forgone care due to health care costs is higher among families with chronic conditions enrolled in HDHPs38. Families with lower incomes are also at higher risk to delay or forgo necessary care, making them an especially vulnerable population3,7,13.

Advisory Board Conclusions

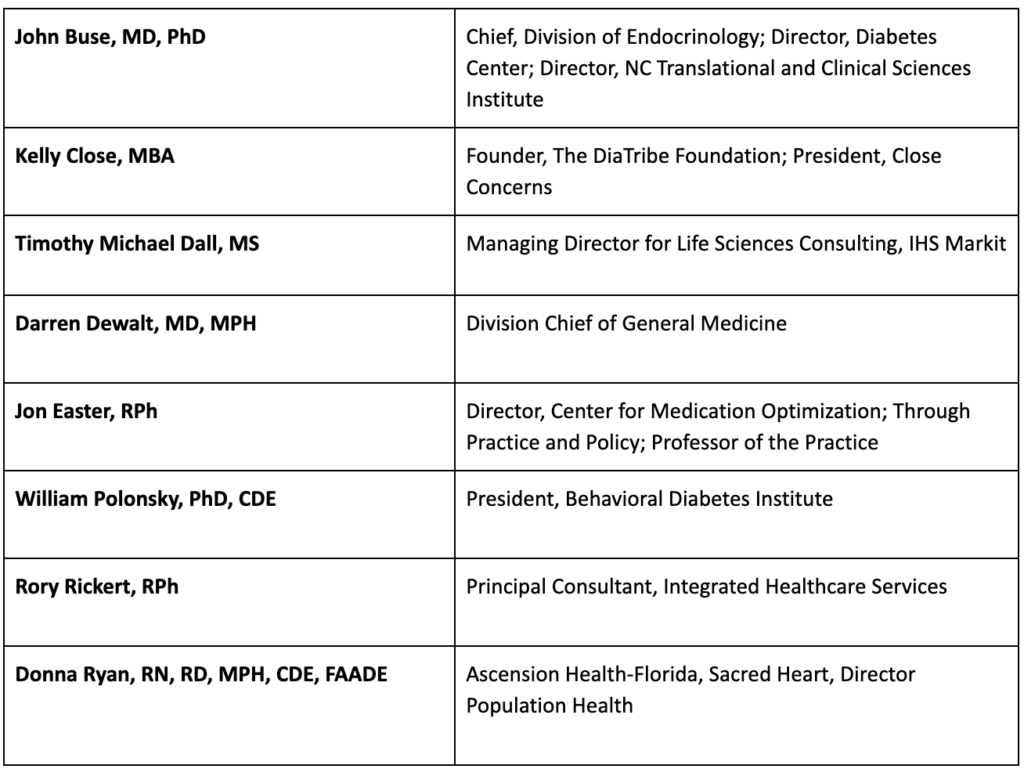

On February 12, 2020 an advisory board was held in which the research team presented the findings from the literature review to a panel of eight national experts representing various fields in the treatment and management of diabetes. The conclusions drawn include recommendations on potential modifications to the HDHP paradigm that might reduce costs while improving health outcomes for PWD.

The advisory panel consisted of the following members:

Recommendations: Policy, Initiatives, And Employers

Based on the literature review plus the discussion with the advisory board, our recommendations are centered around the following three categories: (1) policy implications, (2) special initiatives for PWD, and (3) role of employers.

Policy Implications

The advisory board’s discussion on policy of HDHPs for PWD focused on the benefits of preventative care and patient awareness of what preventative care is covered by insurance. Below is a summary of the main points that were considered.

Preventative Care

In order to achieve better health outcomes and overall cost savings, prevention services and lifestyle interventions must be integrated into care for chronic conditions39. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires insurers to cover medical expenses without cost-sharing for the screening of depression, diabetes, cholesterol, obesity, various cancers, HIV and STIs, as well as counseling for drug and tobacco use, healthy eating and other common health concerns. The costs of immunizations and reproductive health are covered at no costs as well.

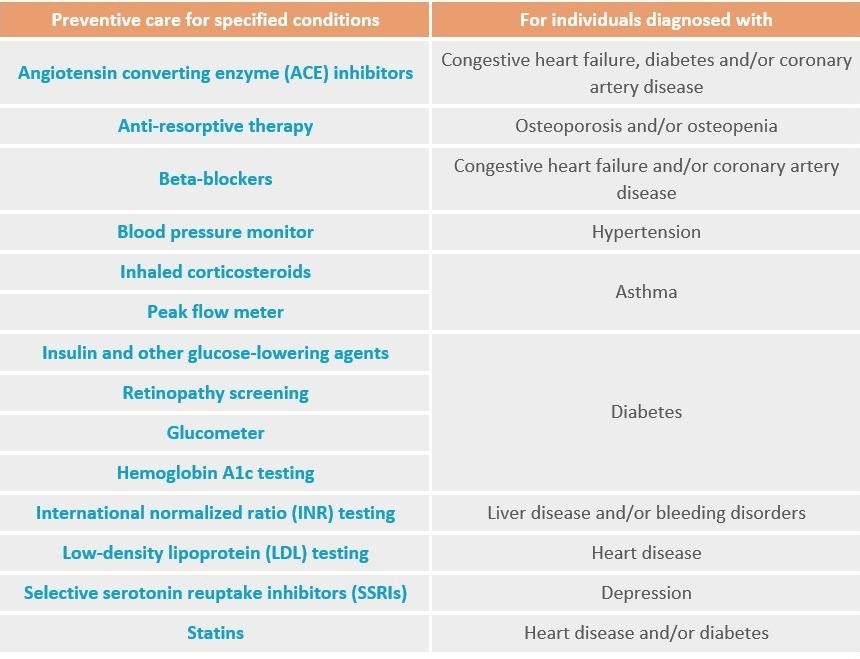

The Trump administration’s recent mandate (Notice 2019-45) expands the list of preventative care benefits required to be provided by HDHPs without a deductible. See the chart below.

Despite the extended preventive care coverage under the ACA and Notice 2019-45, some concerns and challenges still remain specifically for PWD in a HDHP. Two main issues are the coverage limitations for PWD and the awareness of this coverage among patients and providers.

Coverage

The advisory board noted that PWD experience a larger burden of cost with regards to intervention, prevention and maintenance than is recognized. The above-mentioned screening services and preventative care, such as A1C testing and retinopathy screening, are of particular importance to PWD; however, they are not comprehensive.

In addition to the services covered in the recent policies, several prevention services are required for PWD, including kidney disease screening for CKD, foot exams for DPNP, and neuropathy screening. Additionally, multiple ongoing and necessary costs are associated with screening, prevention, testing, monitoring, and maintenance for PWD. These costs accumulate quickly, leaving patients looking for ways to reduce the out-of-pocket spending required by their disease on a regular basis.

Furthermore, as PWD obtain treatment and medication, they must pay at the full list price and are not benefiting from the negotiated discounts if they have not met their deductible. Strong consideration should be given to covering maintenance treatment for PWD in HDHPs. At the least, the net prices should be charged even while PWD are in the process of paying down their deductible.

Awareness

An urgent concern is that prevention and screening services that are covered under the ACA and Notice 2019-45 for HDHPs are underutilized. This creates a critical gap for PWD.

Many HDHP insurance plan enrollees are unaware that the ACA covers preventative care office visits, screening tests, immunizations and counseling with no out-of-pockets charges. Furthermore, it appears patients are also unaware that Notice 2019-45 expands coverage for PWD in a HDHP to include insulin and other glucose lowering agents, retinopathy screening, glucometers and HbA1c testing. We estimate that the majority of patients, and even some healthcare providers, are unaware what these services are and if they are partially or fully covered for people in HDHPs.

We recommend developing two public service awareness campaigns: one campaign targeted to patients and caregivers and another designed for providers. A solution should include a consortia of government, insurers and employers to develop and implement the communication plans.

Special Initiatives For PWD

The advisory board addressed whether specific plans customized for PWD on HDHPs can result in better outcomes while reducing costs, and if so, what it might look like. The discussion focused on two key points: directed care and incentives.

Directed Care

PWD should be offered directed care that is designed to improve health outcomes through financial incentives that reduce costs to patients. One challenge to this approach is that many patients with diabetes are likely to have comorbid conditions. This leads to the issue of prioritizing directed care and determining what are the most important healthcare elements to focus on.

For PWD, key factors include monitoring HbA1c, following dietary guidelines, increasing exercise, and adjusting insulin and other medications. These are daily responsibilities that require time, energy and money.

The impacts of diabetes are not only physical and financial, but also psychological. For PWD that have comorbid conditions, the physical, financial, and emotional burdens associated with chronic illnesses are compounded.

A more specific proposal would be to offer financial rewards such as lower premiums and/or reduction in deductibles for PWD that follow the directed care regimen. If a patient follows a customized protocol as determined by their physician, in turn the patient would receive discounts in their premium, deductible and/or copay.

Research suggests that following directed care would result in better outcomes, which would result in reduced costs. While there are some challenges with validation, the concept should be explored and tested more.

Advances in technology can help in the monitoring of adherence to directed care. Employer Human Resource departments working together with insurers, physicians and health benefits analysts have developed specific patient care. To date, most of these solutions do not change patient behavior, other than to make them consume less, leading to the conclusion that improvements are still needed.

Current best practices of directed care in the primary care space provide an excellent analogue that could be successfully applied to the chronic care space. In primary care, once services are authorized by a third-party/payer, then the services are covered by insurance. The third-party determines where the patient will get the care and what kind of care to get.

Applying this model to patients with chronic disease such as diabetes would be a way to increase the uptake of preventative care, which is already covered, and adherence to continuous treatments to promote better health outcomes. For example, for routine lab tests associated with diabetes, a patient will be notified of a lab nearby that is the most cost effective. The cost is fully covered by the insurer and free to the patient. If the patient goes to a lab that is more expensive, then the insurer pays 80% of the test fees and the patient pays the difference. This insurance design would result in changes in behavior, leading to lower overall costs and, eventually, lower premiums and deductibles for PWD.

In addition to pharmacological approaches, behavioral intervention is a crucial component of diabetes treatment and maintenance. Guidance for various groups of PWD should be provided to inform patients of which behaviors to focus on and will be accompanied with a financial incentive, such as a reduction in the amount of deductible. These elements need to be aligned with having the best pay-off with regards to health outcomes.

If such an ‘incentivized directed care’ program had alignment and buy-in from the broader healthcare ecosystem, then the buy-in and commitment from patients and caregivers would be very high. Ideally a more sophisticated model would include primary and secondary prevention and screening elements as well. Including peer-support and caregivers is an important aspect in adherence.

An incentivized directed care program should be customized to PWD needs; result in better health outcomes; incentivized by a cost-reduction in HDHPs; and address comorbidities. This requires alignment with providers, payers, pharma, and employers.

Incentives

Another topic of discussion centered on what incentives the payer might provide to the patient to help reduce the deductibles. For example, many policies reduce a premium and/or deductible if the person can verify that they are a non-smoker. Some policies tie the body mass index (BMI) to insurance rates. In the past, there were more aggressive incentives in place around lipid management, weight, and disease management programs.

HDHPs should offer an incentive for PWD to maintain good health. For example, if a person’s HbA1c is within a healthy range for a certain amount of time, then their deductible is reduced. This incentive would benefit both parties, as it would (a) result in better health outcomes and reduced out of pocket costs for the patient, while (b) reducing the overall and long term costs for the insurer.

An example is the University of North Carolina’s affiliated health plan which has a program for PWD. If patients join and adhere to the program, the plan will waive copays for their diabetes medications. This offers a demonstration of a value-based benefit design solution.

One potential pitfall of these plans is that some people view the plans as discriminatory. For instance, providing a lower deductible for keeping your weight in check could be discriminatory against those who are genetically predisposed to obesity. Policies should consider putting in place incentives that offer financial rewards of either reducing the deductible or waiving copays for PWD in HDHPs given patients achieve certain treatment and outcome measures.

Role of Employers

The ACA expanding coverage to include preventive care does not mean that health-literate PWD will necessarily engage in preventive health behaviors, such as getting a diabetes screening. There is a need for fundamental changes to educate consumers and provide direction for their care, which could be accomplished through their employer. Patients should not be expected to navigate HDHPs, co-insurance and copays, all while managing their disease, treatment, and other life circumstances. Due to the chronic nature of diabetes, this support is most essential for PWD.

HDHPs have some drawbacks for patients, insurers, and/or employers. As mentioned in the findings from the literature review, patients under HDHPs are financially incentivized to practice poorer health behaviors with their disease, such as forgoing necessary care to save on healthcare costs. Patients that neglect their health have increased absenteeism, implying lower productivity for the employer. As patients with low medical adherence tend to incur more ED visits and hospitalizations that could be avoided, HDHPs create more costs for insurers.

At least two options are available for employer-led policies: zero-dollar copays, and employer benefit plans.

Zero-Dollar Copays

Besides broad PSAs reminding their employees to receive preventative care, employers could also opt into a zero-dollar copay model for all maintenance medications. CVS Caremark materialized this idea with the Rx Zero program, where diabetic patients pay $0 out of pocket for diabetes medication. The National Business Group on Health advocates this idea as Caremark was named one of the best employers for healthy lifestyles.

At present, this program is limited by the types of medications covered under first-dollar coverage in the current HDHP design. A potential solution to this limitation is a pending law that enables insurance companies to design HDHPs that pay for medication for chronic diseases, including diabetes medication (e.g., insulin). Nevertheless, PWD would still pay a net price for their diabetes medication under this law.

Lack of access to employees’ health records limits the employer’s ability to create individual communications and interventions. Employers could follow a similar plan to CVS Caremark and work around the need to provide individualized solutions. A policy with a HDHP for PWD that has a zero copay for maintenance medicine (e.g., generic orals and injectables) would change the paradigm in achieving better outcomes at lower costs.

Employer Benefit Plans

While healthcare should be directed from a patient and provider perspective to improve health outcomes, employers should guide HDHP conversations and policy interventions. There are several opportunities for employers to be more engaged in health promotion, with an added incentive to reduce healthcare costs incurred by the employer.

Employers also have a role in working with insurers to develop ways to reduce the overall cost while improving outcomes. For PWD, adherence is a key variable in reducing ED visits, which in turn, lowers costs. Our literature review suggests that PWD may forgo needed care, which might result in increased absenteeism and lower productivity. In addition to health promotion, it is in both the employer and insurers’ best interests to offer plans that support the best medical adherence, which could result in lower costs, better outcomes, and better work performance.

Employer benefits managers should play a larger role in developing plans that are designed to resolve the major challenges for PWD. The plans need to be simple, communicated, and have incentives that are aligned with reduced costs and better outcomes. Many employers do not have the expertise nor information to develop such solutions. This underscores the importance of collaborating with diabetes experts, insurers, and the pharmaceutical industry to develop a comprehensive solution that is specific to PWD, especially those in HDHPs.

As the employer pays the largest portion of the bill and has the most to gain, employer benefits managers should take a leadership role in coordinating this initiative. In order to maximize the impact, employers should ensure that the policy solutions are informed from a patient perspective. This can be accomplished by including the voice of the employee as well as others in the healthcare ecosystems such as physicians, insurers, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and pharmacies.

Summary Recommendations

Overall, the literature review and expert panel lead to five recommendations.

- Coverage: Policy should be adjusted to allow for maintenance medication and treatment for PWD in HDHPs to be free or low cost. At the very least, PWD should not be charged at list price until the deductible is met. PWD should benefit from the negotiated discounts that are realized after the deductible is met resulting in better outcomes.

- Awareness: Two PSA awareness campaigns should be developed: one targeted to patients and caregivers and another designed for providers. A solution should include a consortium of government, insurers, and employers to develop and implement the communication plan.

- Incentives and Directed Care: Policies should consider putting in place incentives that offer financial rewards of either reducing the deductible or waiving copays for PWD in HDHPs as long as they achieve certain treatment goals and comply with their directed care.

- Zero Copay: A policy with a HDHPs for PWD that has a zero copay covered by employers for maintenance medicine (e.g., generic orals and injectables) would change the paradigm in regards to achieving better outcomes at lower costs.

- Employer Leadership: Benefit managers should lead an initiative to rethink HDHPs and work with patients, providers, and insurers to develop a specific solution for PWD.

Looking Forward

The literature review offered insights about three key themes: (1) income disparity; (2) health insurance literacy; and (3) consumer and health behavior. During the advisory board portion of this project, our advisors investigated those themes further, exploring potential causes, possible solutions, implications on policy, special initiatives for PWD, and the role of the employer. The roundtable led us to identify policy modifications that could be made to accommodate PWD in HDHPs. PWD requires customized solutions, developed with patient-centered approaches, and employers have a key role as catalysts for such solutions.

More research is needed to show that preventative care does indeed result in clear savings for PWD, so that insurers and employers can fully embrace this initiative. Furthermore, directed care is a concept that should be adopted more across the healthcare ecosystem. Patients, providers, and employers should determine where money will be spent, what should be OOP vs. covered for PWD, and in what manner this money will be spent in order to receive the greatest value in return.

Moreover, informed care is a critical success factor for any patient under a HDHP, but especially those with chronic conditions. Distinguishing between different insurance plans and understanding what they cover allows patients and physicians to determine what care is necessary, unnecessary, and discretionary. Based on our findings, diabetes treatments should be more focused on outcomes rather than cost savings. With better health outcomes, PWD could potentially decrease high-cost healthcare expenses such as emergency department visits.

As is the case with many improvement initiatives, these are most effective when the approaches occur concurrently. For example, the directed care and the communications from the employer need to convey the same information and at the same time. All the recommendations have multiplier effects. Together, these recommended improvements on policy, specific initiatives for PWD, and the expanded role of employers, may increase access, reduce costs, and improve outcomes for people with diabetes who have high deductible health plans.

References

- Dolan, R. (2016, February 4). High-deductible health plans. Health Affairs. 10.1377/hpb20160204.950878

- Yao, J., Li, M.S., & Lu, K. (2018). Financial Access to Health Care Use in Diabetics with High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP). Value in Health Journal, 21(3), S136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2018.09.808.

- Rabin, D.L., Jetty, A., Petterson, S., Saqr, Z., Froehlich, A.(2017). Among low-income respondents with diabetes, high-deductible versus no-deductible insurance sharply reduces medical service use. Diabetes Care, 40(2):239-245

- Kirzinger, A., Muñana, C., Wu, B., & Brodie, M. (2019). Data Note: Americans’ Challenges with Health Care Costs. Kaiser Family Foundation.

- Zheng, S., Ren, Z.J., Heineke, J., Geissler, K.H. (2016). Reductions in Diagnostic Imaging With High Deductible Health Plans. Med Care, 54 (2), 110-117. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000472.*Abdus, S., Selden, T.M., & Keenan, P. (2016). The Financial Burdens Of High-Deductible Plans. Health Affairs, 35 (12). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0842

- Buntin, M.B., Haviland, A.M., McDevitt, R., Sood, N. (2011). Healthcare Spending and Preventive Care in High-Deductible and Consumer-Directed Health Plans. American Journal of Managed Care, 17 (3), 222-230. https://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2011/2011-3-vol17-n3/ajmc_11mar_buntin_222to230

- Abdus, S., & Keenan, P. (2018). Financial Burden of Employer-Sponsored High-Deductible Health Plans for Low-Income Adults With Chronic Health Conditions. JAMA Internal Medicine, 178 (12), 1706-1708. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4706.

- Abdus, S., Selden, T.M., & Keenan, P. (2016). The Financial Burdens Of High-Deductible Plans. Health Affairs, 35 (12). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0842

- Galbraith, A.A., Ross-Degnan, D., Soumerai, S.B., Rosenthal, M.B., Gay, C., Lieu, T.A. (2011). Nearly half of families in high-deductible health plans whose members have chronic conditions face substantial financial burden. Health Affairs, 30(2):322- 331.

- Nelson, K.M., Chapko, M.K., Reiber, G., & Boyko, E.J. (2005). The association between health insurance coverage and diabetes care; data from the 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Health Services Research, 40 (2), 361-72. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00361.x

- Agarwal, R., Mazurenko, O., & Menachemi, N. (2017). High-Deductible Health Plans Reduce Health Care Cost And Utilization, Including Use Of Needed Preventive Services. Health Affairs, 36(10). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0610.

- Davis, K., Doty, M.M., Ho, A. How high is too high? Implications of high-deductible health plans. The Commonwealth Fund. 2005;816:i-34.

- Galbraith, A.A., Soumerai, S.B., Ross-Degnan, D., Rosenthal, M.B., Gay, C., & Lieu, T.A. (2012). Delayed and Forgone Care for Families with Chronic Conditions in High-Deductible Health Plans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27, 1105-1111. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11606-011-1970-8.

- Wharam, J.F., Zhang, F., Eggleston, E.M., Lu, C.Y., Soumerai, S.B., Ross-Degnan, D. Effect of high-deductible insurance on high-acuity outcomes in diabetes: a Natural Experiment for Translation in Diabetes (NEXT-D) study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):940-948.

- Wharam, J.F., Lu, C.Y., Zhang, F., Callahan, M., Xu, X., Wallace, J., Soumerai, S., Ross-Degnan, D., Newhouse, J.P. High-deductible insurance and delay in care for the macrovascular complications of diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(12):845-854.

- Wharam, J.F., Landon, B.E., Galbraith AA., Kleinman, K.P., Soumerai, S.B., Ross-Degnan, S. (2007). Emergency department use and subsequent hospitalizations among members of a high-deductible health plan. JAMA, 297 (10), 1093-1102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17356030.

- Loewenstein, G., Friedman, J.Y., McGill, B., Ahmad, S., Linck, S., Sinkula, S., Beshears, J., Choi, J.J., Kolstad, J., Laibsoni, D., Madrianj, B.C., List, J.A., Volpp, K.G. Consumers’ misunderstanding of health insurance. J Health Econ. 2013;32(5):850-862.

- Reed, M., Fung, V., Price, M., Brand, R., Benedetti, N., Derose, S.F., Newhouse, J.P., Hsu, J.. High-deductible health insurance plans: efforts to sharpen a blunt instrument. Health Affairs. 2009;28(4):1145-1154.

- Reddy, S.R., Ross-Degnan, D., Zaslavsky, A.M., Soumerai, S.B., & Wharam, J.F. (2014). Impact of a High-Deductible Health Plan on Outpatient Visits and Associated Diagnostic Tests. Med Care, 52(1), 86-92. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000008.

- Bajari, P., Hong, H., & Khwaja, A. (2006). Moral Hazard: Adverse Selection and Health Expenditures: A Semiparametric Analysis. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w12445.pdf.

- Cohen, A., & Siegelman, P. (2010). Testing for Adverse Selection in Insurance Markets. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 77 (1), 39-84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6975.2009.01337.x.

- Handel, B.R. (2013). Adverse Selection and Inertia in Health Insurance Markets: When Nudging Hurts. American Economic Association, 103 (7), 2643-2682. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42920667.

- Dixon, A., Greene, J., & Hibbard, J. (2008). Do Consumer-Directed Health Plans Drive Change In Enrollees’ Health Care Behavior? Health Affairs, 27 (4). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.1120.

- Naessans, J., Khan, M., Shah, N., Wagie, A., Pautz, R. & Campbell, C. (2008). Effect of Premium, Copayments, and Health Status on the Choice of Health Plans. Medical Care, 46 (10), 1033-1040. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318185cdac.

- Fendrick, A., Buxbaum, J., Tang, Y., Vlahiotis, A., McMorrow, D., Rajpathak, S., Chernew, M.E. (2019). Association between switching to a high-deductible health plan and discontinuation of type 2 diabetes treatment. JAMA Netw Open, 2(11). e1914372-e1914372.

- Jetty, A., Patterson, S., Rabin, D.L., Liaw, W. (2018). Privately insured adults in HDHP with higher deductibles reduce rates of primary care and preventive services. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 8 (3), 375-385. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibx076.

- Dafny, L.S, & Lee, T.H. (2016, December). Health Care Needs Real Competition. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/12/health-care-needs-real-competition.

- Ellis, R.P. & McGuire, T.G. (1993). Supply-Side and Demand-Side Cost Sharing in Health Care. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(4), 135-151. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.7.4.135.

- Hamel, L., Firth, J., & Brodie, M. (2014, March 26). Kaiser Health Tracking Poll: March 2014. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-march-2014/.

- Ho, K., & Lee, R.S. (2017). Insurer Competition in Health Care Markets. Econometrica, 85 (2), 379-417. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA13570.

- Kullgren, J.T., Cliff, B.Q., Krenz, C.D., Levy, H., West, B., Fendrick, M.A., So, J., Fagerlin, A. A survey of Americans with high-deductible health plans identifies opportunities to enhance consumer behaviors. Health Affairs. 2019;38(3):416-424.

- Porter, M.E., Kaplan, R.S.. How to pay for health care. Harv Bus Rev. 2016;94(7-8):88-98.

- Huckfeldt, P.J., Haviland, A., Mehrotra, Z.W., & Sood, N. (2015). Patient Responses to Incentives in Consumer-directed Health Plans: Evidence from Pharmaceuticals. The National Bureau of Economic Research, 20927. 10.3386/w20927.

- Reiss, S.K., Ross‐Degnan, D., Zhang, F., Soumerai, S.B., Zaslavsky, A.M., Wharam, J.F. Effect of switching to a high‐deductible health plan on use of chronic medications. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(5):1382-1401.

- Greene, J., Hibbard, J., Murray, J.F., Tetusch, S.M., Berger, M.L. (2008). The Impact Of Consumer-Directed Health Plans On Prescription Drug Use. Health Affairs, 27 (4), 1111-1119. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.1111.

- Wintergerst, K.A., Hinkle, K.M., Barnes, C.N., Omoruyi, A.O., & Foster, M.B. (2010). The impact of health insurance coverage on pediatric diabetes management. ScienceDirect, 90 (1), 40-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2010.06.013.

- Lewey, J., Gagne, J., Franklin, J., Lauffenburger, J., Brill, G., Choudhry, N. Impact of high deductible health plans on cardiovascular medication adherence and health disparities. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11(11):e004632.

- Nair, K.V., Park, J., Wolfe, P., Saseen, JJ., Allen, RR., Ganguly, R. (2009). Consumer-driven health plans: impact on utilization and expenditures for chronic disease sufferers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 51 (5), 594-603. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31819b8c1c.

- Ogden, L.L., Richards, C.L., & Shenson, D. (2012). Clinical Preventive Services for Older Adults: The Interface Between Personal Health Care and Public Health Services. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 419-425. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300353.

This research was supported by the UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School’s Center for the Business of Health. Funding was provided by Eli Lilly and Company.