Brian R. Golden and Rosemary Hannam, Sandra Rotman Centre for Health Sector Strategy, Rotman School of Management

Contact: Brian.Golden@Rotman.Utoronto.Ca

Abstract

What is the message? On the surface, single-payer health systems seem especially well-suited to implement value-based, bundled payment initiatives. Focusing on a failed attempt to create a bundled payment system for wound care in the Canadian province of Ontario, we describe features of single-payer systems that are supportive of such initiatives, while also discussing features of single-payer systems that put them at a disadvantage. We examine the necessary links between strategic goals (e.g., achieving greater value), structure, and systems; the lessons learned from an early unsuccessful value-based care effort; and more recent successes based on these learnings.

What is the evidence? The authors helped design the Integrated Client Care Project in Ontario during the early 2010s.

Submitted: September 15, 2020; accepted after review September 28, 2020.

Cite as: Brian R. Golden & Rosemary Hannam. 2021. The Promises and Challenges of Value Based Care and Bundled Reimbursements in Single-Payer Health Systems. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI.org), Volume 6, Issue 1, Winter 2021.

Value Based Care May Help Solve Health Systems Fragmentation

Health system managers, policy makers, and scholars have long bemoaned the siloed, or fragmented, nature of health systems across the globe — some, of course, more fragmented than others. Michael Porter and Elizabeth Teisberg [1] seized upon this weakness of health systems, arguing that many providers along the value chain take extremely parochial perspectives, optimizing for themselves and sub-optimizing at the system level. They argued that this is manifested in, among other things, attempts to pass risk to other players in the system, the inability to attribute both positive and negative performance to providers, redundancies in care resulting in bloated costs, and poorly coordinated care for patients who are often left to navigate obtuse pathways to care.

The Porter and Teisberg framework popularized the concepts of value and bundled care, along with bundled payments, and has since been expanded in more recent work [2 3]. Because this framework is now well known, we will simply articulate the core principles here:

- Organize into Integrated Practice Units (IPUs)

- Measure outcomes and costs for every patient

- Move to bundled payments for care cycles

- Integrate care across separate facilities

- Expand excellent services across geography

- Build an enabling information technology platform

The two authors of this article, based in the Canadian province of Ontario, began conversations with Michael Porter shortly after the Porter and Teisberg framework began to show influence in several health systems, mainly outside of the U.S. (e.g., Sweden, Finland, Taiwan, Germany).[1] We three saw an opportunity to apply the principles of Value-Based Care, including bundled payments, in the politically important, fiscally significant, and by most accounts clinically challenged domain of home care services — and specifically, in the care associated with wound treatment. In order to educate Ontario health system leaders about the principles of Value-Based Care (VBC), we invited Porter to visit with health system leaders, subsequently followed by meetings and workshops in Boston with the two authors, Porter and his colleagues, and several Ontario health system leaders including two Ministers of Health.

This article describes our early experiences attempting to implement value-based care, including bundled payments, in Ontario beginning in 2008. Many of us leading the initiative, including government officials and the two authors, believed that a single-payer system was a particularly appropriate setting to implement VBC. Unfortunately, we were wrong. This initiative, referred to as the Integrated Client Care Project (ICCP) was, in our view and of an evaluation team’s, largely a failure [4] judged against the goals of implementing the VBC principles articulated by Porter and colleagues. However, as an early VBC initiative it was highly instructive for Ontario and later other provinces in understanding the challenges of implementing VBC, and bundled payments, in single-payer health systems.

In the remainder of this article we describe the provincial health system in Ontario (similar to most Canadian provinces), the ICCP, the challenges faced in its implementation, lessons learned, and more recent advances informed by our early VBC initiative. Central to our argument is that while single-payer systems may, on the surface, seem particularly amenable to the implementation of VBC, they also pose unique and significant challenges. Our perspective on these challenges, and ways to address them, are framed around the early organization-design work of Galbraith [5], extended by Golden and Martin [6] to the design of health systems.

Ontario’s Health System And The Integrated Client Care Project

Ontario is Canada’s most populous province with approximately 13 million of the country’s 33 million residents in 2008, the year the ICCP was launched. As are all provinces, Ontario is subject to the Canada Health Act of 1984, which created the current version of Medicare. The Act designates the provinces as the single-payer for all medically necessary health services and includes the following provisions:

- No user-fees or extra-billing

- Universality: Available to all Canadians[2]

- Comprehensive: Covers all medically necessary services

- Accessible: No barriers to use

- Portable between provinces

- Publicly administered

Coming out of our meetings with top Ontario government officials (i.e., the two health ministers), Michael Porter, and his colleagues, there was a view that the single-payer nature of Ontario’s health system — whereby the government is able to influence all providers by virtue of the funder’s “power of the purse” —- would overcome many of the challenges experienced at that time implementing VBC principles in health systems lacking unitary governance, such as across the U.S. Consequently, the two authors worked with the Ministry of Health (hereafter the “Ministry”) to identify a care setting for the province’s first VBC initiative. As part of a three-way collaboration between our research team, the Ministry and industry providers, the decision was made to launch the ICCP in the home care sector.

The ICCP was targeted at home-based wound-care. As described in an independent review of the ICCP outcomes:

Although not always recognized as a pressing health care problem, wounds are a common, complex, and costly condition [1]. Approximately 1.5 million Ontarians will sustain a pressure ulcer, 111,000 will develop a diabetic foot ulcer, and between 80,000 and 130,000 will develop a venous leg ulcer [1]…. The estimated cost to care for a pressure ulcer in the community in 2006 was $27,000 CDN… Community-based care for people with wounds is often fragmented and inconsistent, leading to prolonged healing times and ineffective use of resources. [4]

Importantly, clinical researchers in wound-care are largely in agreement about clinical best practices to treat wounds at home [7]. Additionally, there is consensus that quality care requires effective coordination and communication of an interprofessional team of physicians, nurses and other health-care providers working together. This interdependency among providers aligns with Porter’s concept of an Integrated Practice Unit whereby an interprofessional collective works together and is mutually accountable for outcomes.

Further arguing for our focus on wound-care, prior Ministry work had determined that there were significant departures from clinical best practice across the province, inconsistencies in outcome measurement and reporting — although there was consensus on the most appropriate outcome measures — and related, significant variation to the costs of care. Specifically, Shannon had recently shown that “best practice” resulted in a 60 percent saving over current practices. [7]

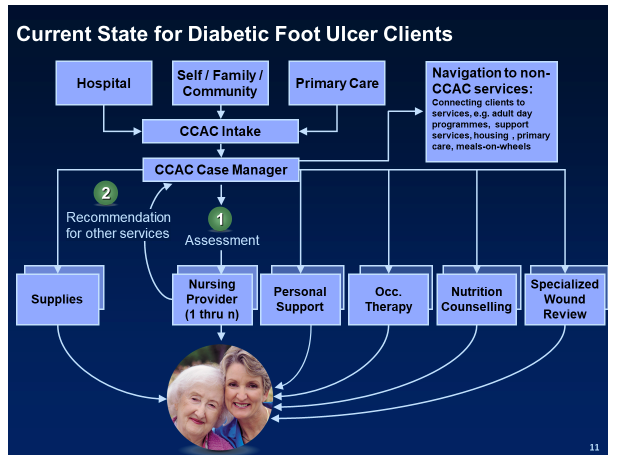

Pre- Integrated Client Care Project

Prior to the launch of the ICCP, home care for patients with wounds (e.g., diabetic foot ulcers, the focus of the ICCP) was provided by a variety of independent, uncoordinated healthcare professionals and organizations. The typical care pre-ICCP care model for patients is presented in Figure 1. As illustrated, a patient requiring wound care could be referred to the Community Care Access Centre (CCAC) — a provincially funded home care coordinating agency — by the patient’s hospital, through self-referral, or by a primary care provider. The CCAC would then assign a case manager whose role it was to assess the client’s care needs, authorize service, coordinate care, and provide system navigation. Medical supplies for the wound (dressings) would be ordered for patients according to their specific needs. Importantly, equipment needed by the patient was not covered by CCAC funding and could only be purchased by the patient if they had private insurance or qualified for government support.

On the surface, this CCAC case manager coordination appears well-designed and built around the patient. Ministry reviews, however, showed this not to be the case. For example, the nursing agency would complete a nursing assessment and develop a nursing “care plan.” Separately, the occupational therapy provider would visit the patient, conduct their own assessment, and complete another care plan. Likewise, for the nutrition service provider. Approximately sixty percent of each assessment by each specialized care provider, employed by different organizations, was identical to the one before and after it, with the remainder specific to their discipline.

Numerous other design features of the wound care process were known to impede effective care:

- Nurse’s generalist training versus the necessary wound care expertise; home care nurses were assigned by the case managers according to a contractually negotiated rota, and not based on specialized wound care expertise

- Fee for service contractual arrangements with all providers with no quality or patient outcome adjustments; progress defined as the number of treatment interactions

- Service typically provided by caregivers employed by different organizations, and these different organizations and their employees had no mechanisms to share information; each provider had its own, proprietary health record

- Patients would rarely be assigned a single caregiver, so even within a provider organization (e.g., nursing agency) continuity of care and inter-nurse communication was challenging

- Service providers requested supplies through the CCAC. Since there were often multiple providers in the home, with no mechanism to coordinate among them, it was common to over-order or to be short on supplies. This often resulted in unnecessary and costly extra visits when supplies were not delivered as planned (e.g., a nurse visiting the home to change dressings which had not been delivered)

We find an airline metaphor to be most useful in describing the disfunction of the pre-ICCP experience. Imagine boarding a flight where the captain, first-officer, and second officer meet for the first time moments before your flight, are employed and were trained by different airlines, for different aircraft, and speak different languages. Imagine the same sort of coming together, for the first time, for the cabin crew, mechanics, air traffic controllers, caterers. How comfortable would any one of us be on such a flight, even recognizing that the different ad-hoc teams (e.g., the cabin crew) have the luxury of being in the same “room” at the same time, and of course have the incentive — equal to passengers — of a successful flight?

The situation we witnessed in the wound care system was far worse than the flight example above; no such opportunity for coordination or flight-crew/passenger alignment of interests existed in Ontario’s home-care setting. Poor coordination and low-quality care only impacted the patient and the costs to the system but had no negative consequences to any of the provider organizations.

Figure 1

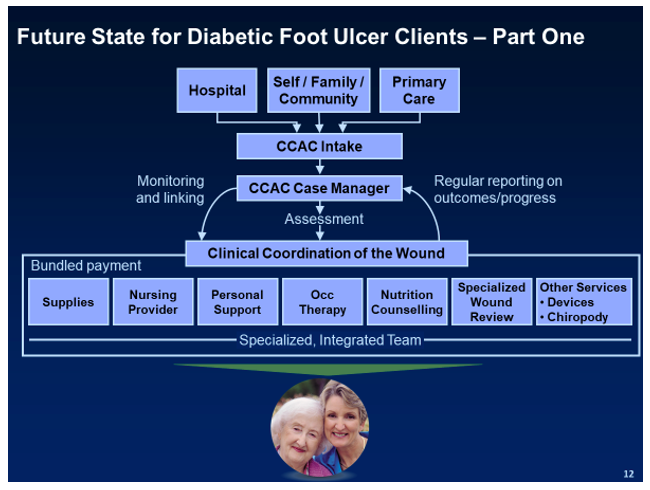

Integrated Client Care Project

The ICCP was designed to address the weaknesses by implementing the VBC framework of Porter and colleagues. Specifically, we designed a new approach of providing wound-care at home around six principles:

- Specialized case-management

- Coordinated assessment among providers

- System-wide navigation and integration

- Care delivered by integrated clinical service teams

- Informed by clinical best practice

- Rewards based on outcomes and encouraging innovation

The project was governed by a tri-partite structure made up of the Ministry, The Ontario Association of CCACs (OACCAC) and researchers at the University of Toronto. Importantly, ultimate decision-making authority lay with the Ministry.

The planned new model of care is reflected in Figure 2 and was undertaken in four of Ontario’s health regions. Under the ICCP, four[3] CCAC & home care agency pairs (one in each region) were selected through a voluntary application process to participate. The home care agency would be designated as the “bundler”. To illustrate, we refer to one of these bundler agencies as Home Care Ontario (HCO). HCO would be contacted by a CCAC case manager each time a patient met the criteria under the ICCP (e.g., suffering from a diabetic foot ulcer, at home, requiring inter-disciplinary team-based care).

Figure 2

Upon receiving notification from the CCAC after an initial assessment of needs, HCO would assign a clinical coordinator responsible for the collective activities — and outcomes —- of care providers. HCO’s coordinator, having prepared for a significant volume of similar clinical cases in the health region, would assemble a team of clinicians (e.g., nursing, nutritionists, occupational health, etc..) who specialize in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. As in the pre-ICCP era, some of these caregivers would be employed by organizations contracted by HCO. In other cases, HCO would hire these caregivers and bring these capabilities in-house. Communication between these specialized team members and between the team and the client would be now streamlined, a function of common training and purpose-built information systems/EMRs, the costs of which would be justified by the contractually guaranteed volume of cases assigned to HCO.

As part of the ICCP, HCO would receive a bundled payment that would be set by the Ministry at some to-be-determined price between the cost of best practice and the median price it was currently paying across the province. Recall the 3x fold difference between the current cost of care in Ontario versus the lower cost for best-practice care [7] awarded to HCO for meeting pre-determined evidence based outcome indicators (e.g., size of wound, healing rate, infection or other complication, wound related pain intensity. Naturally, potential bidders such as HCO would only bid for contracts based on its belief that it could deliver quality care at a cost below the price the Ministry had set.

Providing both an opportunity and incentive to HCO, coordinators were given the discretion to rebalance the time assigned to various care givers within its inter-disciplinary team (e.g., physio over more expensive nursing). HCO was also free to make evidence-based judgements around the use of supplies; supplies are closely connected to the effective care of wounds. For example, dressing A may require daily changes (which equals daily nursing visits) whereas dressing B may need changing only twice a week. Often, a dressing that requires fewer changes is more expensive, but there can be savings in terms of reduced healing times and fewer nursing visits. If the HCO team collectively controls both the supplies and the nursing visits, and knows and communicates the specifics of the client’s situation, they can view all inputs as a total package and, since they are being rewarded for outcomes and cost reduction, make the decision that will lead to the best, least expensive outcomes for the patient.

In another instance, HCO might make the decision to purchase of a $150 orthotic or air cast to relieve the pressure on an ulcer when walking. Pre-ICCP such devices could not be purchased by the CCAC. Under the bundled care project HCO could purchase this device as needed, thus leading the patient to ambulate more quickly, speeding recovery, reducing needed nursing visits, and also reduce total costs of care. As can be clearly seen, these examples of the planned bundled care and reimbursement provide a stark contrast to home care prior to the launch of the ICCP.

What actually happened?

The ICCP was launched in a system that seemed particularly amenable to implementing the principles of VBC, including bundled reimbursements. As mentioned above, the single-payer quality of Ontario’s system was expected to give the Ministry of Health the “power of the purse” to align the various design features of the health system needed to implement VBC. Further arguing for this initiative, the medical condition of diabetic foot ulcers was well aligned with the principles of VBC (e.g., well accepted and understood clinical best practices and quality measures, the requirement for multi-professional care, and significant opportunities to reduce costs). Yet, despite these positive prior conditions there was significant divergence between the ICCP intervention as intended and as implemented [4].

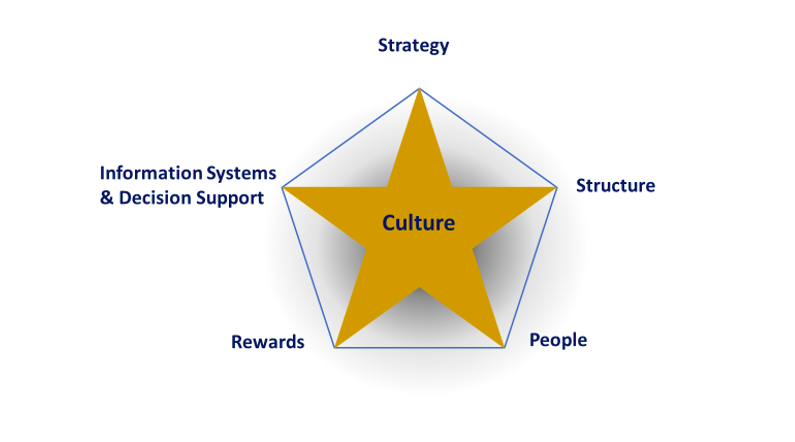

Our analysis of the reasons for this divergence is instructive for future VBC initiatives, particularly in single-payer systems. The analysis draws on the organization and system design framework presented in Figure 3 [5 6]. The underlying logic of this framework is that system structure, people systems, rewards, and information systems and decision support must be designed to support strategic goals, that all of these “points on the star” must be aligned — or supporting the others, and the decisions made about these points on the star (e.g., what to pay for and what not to pay for) influence the culture (i.e., values) of the organization/system.

We argue below that the ICCP was mainly unsuccessful due to the misalignment of these system design elements and that this misalignment was largely due to the cooptation of the project by the OACCAC. However, the ICCP was successful in germinating insights that have subsequently led to more successful value based and bundled payment initiatives.

Figure 3

The ICCP and the Star Model

Strategic Goals: The strategic goal of the ICCP was to provide better value for the payer and the patient. Specifically, this meant lower total costs, less variability in costs, and a better patient experience, including but not limited to clinical outcomes.

Structure: As illustrated in Figure 2, from a structural perspective, the ICCP was intended to bring all needed caregivers under one governance structure. Unfortunately, this never occurred. The Ministry, due to its long-standing conflicts with the Ontario Medical Association (essentially the physician’s trade union), was unwilling to broach the subject of structural and compensation changes with physicians. As a consequence, physician care —- central to the care and associated costs of wound care —- remained outside the IPU. Similarly, HCO as the “bundler” did not receive a contract for the full cycle of care for the wound as initially planned, nor any control over the pharmaceutical or the wound supplies budget, representing another limitation to how it could reallocate resources to achieve better value. Finally, the partner organizations that were part of the IPU and contracted by HCO were all separate corporations with no experience working with each other and unwilling to share proprietary costing data.

People Systems: By people systems we mean both kinds of people (e.g., nurses, physiotherapists) and how they are managed (e.g., training). Porter and his colleagues have argued that one of the benefits of IPUs is the opportunity to staff them with specialized caregivers. Unfortunately, the contract awarded to the “bundlers” (e.g., HCO) in the four regions did not provide sufficient patient volume to justify this kind of assignment or specialized training.

Other skill or experience deficiencies were also observed, and some were unique to single-payer government funded systems. For example, the bundlers and the providers they hoped to contract with lacked the governance skills of partnering and contracting. Also, Ontario’s health system has a dearth of professionals with actuarial skills; the historical payment models to providers did not account for patient characteristics.

As a result, both the Ministry and the bundlers lacked the skills to determine a reasonable level of bundled payments (Ministry) and the costs to provide care (HCO and its contracted partners). This led to a reluctance by the Ministry to set what it feared would be too high a bundled payment price and by HCO to seek a contract and bundled price from the Ministry as per the original plan, as they were unsure if the bundled price would cover their costs. The source of this lack of capabilities comes from the centrally planned, non-market environment of healthcare provision in Ontario.

Rewards: Central to the VBC framework is a payer which is able to determine a sufficiently attractive price, the bundled payment, to attract the interest of providers to form an IPU and make specialized investments that would result in improved outcomes for the dollars awarded providers. As described above, the critical physician services were carved out of the bundled payments. Also, because of a lack of historical market data, as well as actuarial and cost accounting capabilities, the Ministry was unable to determine a price somewhere in the “sweet spot” between what it was previously paying for foot ulcer care and the bundlers’ collective costs for providing care. In fact, the bundlers were not able to confidently determine their full costs of care, in part because of underdeveloped costing capabilities and because the organizations they planned to contract with were unwilling to share proprietary data. There was also a lack of confidence in defining eligibility criteria and including stop/loss provisions to cover unexpected exceptional cases. As a consequence, bundlers attempted, unsuccessfully, to negotiate a large safety cushion in their pricing to avoid possible cost overruns.

Information and Decision Support Systems: Porter and Lee [2] describe the critical role played by information systems vis-à-vis VBC. Again, partly because of the lack of market forces in the Ontario health system, but also because of historical funding practices (i.e., “global funding” such that providers would typically receive some inflation adjusted funding over the prior year, regardless of the volume or quality of care provided). The consequence of past practices, as well as the uncertainty of the ICCP’s future, bundlers were unwilling to invest in specialized information and decision systems. Those involved in the ICCP pilot projects had to track patient data manually, which ultimately proved to be overwhelming. As a consequence of this information deficiencies, providers such as HCO were reluctant to take on larger future contracts.

Lessons Learned and Applied

While single-payer, publicly funded systems should have an advantage over more fragmented systems in the implementation of VBC, and this appeared to be the case at the outset of ICCP, in fact many of the capabilities needed were underdeveloped or totally lacking. The ICCP exposed these unexpected deficiencies and as a result the four pilot sites for ICCP were unable to set up and align the four design elements (“points on the star”) needed to support the strategic goal of better outcomes for dollars spent. Nonetheless, and while disappointing at the time, this early failure had a positive effect in that the initial stages of exposing Ministry leadership to Porter and Teisberg’s ideas had seeded an appreciation for the benefits of VBC and a recognition that the alignment of strategy, structure, people, rewards and decision support systems would be critical to future successes.

In the remaining part of this paper we focus on subsequent VBC initiatives that benefited from the ICCP experiment and make recommendations for others going forward, particularly in single-payer systems. We have selected examples under each “point” on the star to illustrate recent progress.

Structure: The CEO of St. Joseph’s Healthcare System in Hamilton, Ontario was part of the group of industry leaders who travelled to Boston to attend Porter’s three-day VBC workshop, and upon return spent time exploring ways to introduce VBC in his health system. After two years of study, and supported by the Minister, St. Joseph’s introduced a VBC pilot project focused on five acute medical conditions – COPD, CHF, hip and knee joint replacements, and thoracic surgery.

The initiative, called the St. Joseph’s Integrated Comprehensive Care Program (SJ-ICCP), began in April 2012 and was more closely aligned to the principles of VBC, including bundled payments, than the home care ICCP. In particular, the Ministry would award St. Joseph’s a bundled payment for what had previously been discrete and fragmented payments to various providers.

There were two notable improvements over the prior failed ICCP. First, all care providers except for physicians were included in the bundle — and all of these providers were employed by one of St. Joseph’s owned corporate entities (e.g., hospitals, home care, long-term care, etc..). The “bundler” for home care services was not the CCAC but instead St. Joseph’s own home care agency, which meant it was possible to create and assign a consistent homecare team for patients once they were discharged from hospital. Supplies and equipment were also included. Second, although physicians were not included in the payment structure, they were included in the planning and implementation, and experienced many benefits of the VBC initiative including improved patient outcomes, shorter length of stay, increased physician productivity (and therefore higher fee-for-service income) and a vastly improved patient experience.[4]

People Systems: The SJ-ICCP in Hamilton also demonstrated the value of an expert team dedicated to caring for patients within each medical condition. Assigning specialized care providers, including coordinators and personal support workers (PSWs) who had specialized training, allowed the teams to provide patient-centered care of higher quality and lower costs. For example, common post-surgical issues could be handled by phone or a visit by a nurse, without triggering a visit by the patient to the hospital. This resulted in a better patient experience and lower provider costs.

In addition, a province-wide initiative announced in April 2012, called “Quality-Based Procedures” (QBP) introduced activity-based costing to Ontario hospitals, prompting the development of costing and actuarial skills within hospital finance teams and the Ministry. Beginning with hip and knee replacements and expanding to other surgical and medical conditions over the last eight years, the QBP movement has created incentives for hospitals to develop capabilities to track costs and improve efficiency [8]. It has also encouraged specialized care teams, similar to the SJ-ICCP, as well as partnering with rehabilitation services and home and community care providers.

Rewards: The introduction of QBPs, which sets a price for each procedure, prompted a series of consultations between government, academics, and clinical advising teams to create best practice pathways and to determine corresponding costs to arrive at a mutually-agreed upon price for each procedure. Details can be found on the Health Quality Ontario (now Ontario Health) website.

Information and Decision Support: The focus on QBPs in Ontario has sparked investments in information and decision support capabilities, particularly in hospitals; recall, the home care ICCP revealed the importance of – and deficiencies in — these capabilities in the health system. Since then, consistently measuring how much it costs to deliver all aspects of care for a knee replacement surgery, for example, and comparing this total cost to the QBP rate, has been recognized as an essential strategic capability within the hospital sector. Similar capabilities are now emerging in the home and community care sectors.

Although the intention is there, both the measurement of outcomes and inclusion of outcomes in the contract for care delivery, particularly those focused on the patient experience, is still in development [9]. Movement has been slow, but encouraging signs are appearing, for instance in pan-Canadian organizations such as the Canadian Foundation for Health Improvement, the Canadian Institute for Health Information, and Canada Health Infoway, which are now investing in tools to enable all providers to measure outcomes [10].

Ontario Health Teams: In 2019, building on the progress of individual pilot projects, the Ministry introduced a new organizational form to deliver care throughout Ontario — Ontario Health Teams:

“… groups of health care providers and organizations that are clinically and fiscally accountable for delivering a full and coordinated continuum of care to a defined geographic population.”[5]

This new model, similar to the U.S.’s accountable care organizations, is designed to bring together the progress made in each element described above, and lays the groundwork for VBC, including bundled payments. But like the ICCP, it will be imperative for physician services to be included in the bundles.

Currently the Ontario Medical Association remains hesitant to alter physician funding, stymieing attempts by the Ministry to create outcome-based bundled payments. Some optimism is called for, however, as VBC models, including bundled payments, may create the opportunity for physician groups to benefit from health system cost savings.

Looking Forward

Our interest in working with Ontario’s Ministry of Health was in leveraging some of the ostensible advantages of a single-payer system to implement the VBC principles articulated by Porter and colleagues. While single-payer systems have obvious advantages such as the government’s power of the purse, and legislative authority to mandate quality targets, our experience with the ICCP and later VBC initiatives reveals that single-payer systems may also lack the sophisticated systems necessary for successful implementation. As suggested above, precisely because they are single-payer systems — an in the case of Ontario, with only not-for-profit, community-based hospitals — they often lack costing and pricing systems, effective information systems to coordinate care and measure performance, and critical human resource capabilities such as actuarial skills found in more competitive market-based systems.

We remain optimistic that single-payer systems can benefit from the principles of VBC, and the implementation of bundled payments. However, before this promise will be realized, several challenges of system alignment must be addressed, and the alignment model presented here can be instructive.

Several questions embedded in that model will need to be addressed in the affirmative. For instance:

- Are there organization and governance structures in place to form IPUs and support cooperation among provider partners?

- Do payers, providers and their staff have the requisite human resource/people skills to support VBC, including pricing and costing capabilities, and partnering skills?

- Are there sufficient rewards to induce risk sharing between payers and providers? Are there mechanisms to assign rewards to the providers creating value for patients and payers?

- Are information and decision support systems available to providers to support the delivery of high value patient care, and to payers so they can monitor and reward performance?

Our experience with ICCP and subsequent VBC initiatives in Ontario shows that single-payer systems do have many features that make them amendable to rewarding for value, and doing so in the form of bundled payments. However, such systems also have historical and unique challenges that must be overcome to achieve the promise of Value-Based Care that so many health systems today are pursuing.

References:

[1] Porter, Michael E, and Elizabeth O. Teisberg. 2006. Redefining Health Care. Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

[2] Porter, Michael E., and Thomas H. Lee. 2013. “The Strategy That Will Fix Health Care.” Harvard Business Review 91 (10): 50-70.

[3] Porter, Michael E, and Robert S. Kaplan. 2016. “How to Pay for Health Care.” Harvard Business Review 94 (7/8): 88-102.

[4] Zwarenstein, M, K Dainty, and S Sharif. 2015. “www.ices.on.ca.” March. Accessed September 13, 2020. https://www.ices.on.ca/~/media/Files/ICCP/ICC-Wound-Care-Evaluation-Final-Report.ashx?la=en-CA.

[5] Galbraith, JR. 2001. Designing Organizations: An Executive Guide to Strategy, Structure, and Process. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishing.

[6] Golden, Brian R, and Roger L Martin. 2004. “Aligning the Stars: Using Systems Thinking to (Re)Design Canadian Healthcare.” Healthcare Quarterly 7 (4): 34-42.

[7] Shannon, Ronald J. 2007. “A Cost-Utility Evaluation of Best Practice Implementation of Leg and Foot Ulcer Care in the Ontario Community.” Wound Care Canada S53-S56.

[8] Trenaman, L, and Jason M Sutherland. 2020. “Moving from Volume to Value with Hospital Funding Policies in Canada.” HealthcarePapers 19 (2): 24-35.

[9] Sutherland, Jason M. 2019. “Using Data to Move from Volume to Value.”

HealthcarePapers 18 (4): 4-8.

[10] Horne, F, and Rachael Manion. 2019. “A Made-in-Canada Approach to Value-Based Healthcare.” HealthcarePapers 18 (4): 10-19.

Notes:

[1] Interestingly, in our conversations with Porter, he indicated the slower progress in influencing the U.S. system because of its extreme fragmentation.

[2] A small percentage of residents are excluded from the Canada Health Act, including indigenous Canadians (who have separately funded system)

[3] The four pairs included four separate CCACs and three home care agencies, as one agency was the partner in two regions.

[4] https://www.stjoes.ca/hospital-services/integrated-comprehensive-care-icc-

[5] http://health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/connectedcare/oht/#:~:text=Ontario%20Health%20Teams%20are%20groups,to%20a%20defined%20geographic%20population.