Jiayin Xue and Kevin Schulman, Stanford University

Contact: Kevin.Schulman@Stanford.Edu

Abstract

What is the message? Medicare Advantage (MA) plans have been gaining popularity in recent years, but how do they differ from traditional fee-for-service Medicare programs, and how do MA plans impact patient care? We outline a brief history of traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, and a comparison of cost, quality, patient care outcomes, and impact on care delivery innovations in the last decade.

What is the evidence? Published medical literature, reports from the government and policy institutions, publicly available information on select care delivery organizations

Submitted: December 30, 2020; accepted after review: January 7, 2021.

Cite as: Jiayin Xue, Kevin Schulman. 2021. A Narrative Review of Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI.org), Volume 6, Issue 1, Winter 2021

Please see an Addendum below in response to the growing debate over the true cost of Medicare Advantage.

What is Medicare Advantage and How Is It Changing?

Medicare is a blend of the traditional fee-for-service program (TM) and separate programs run by commercial health plans. In recent years, commercial plans (Medicare Advantage or MA plans) have been gaining popularity. MA enrollees now account for over 34% of Medicare beneficiaries.1 Medicare expansion proposals have also garnered much attention during the 2020 Democratic primary campaign, some of which proposed elimination of all commercial payers, others retained MA and other types of private options. Given the increasing interests from both patients and policy makers, we explore the origin of MA and what is known about the impact of the program on Medicare beneficiaries in this narrative review.

Previous studies have indicated that the quality of care between traditional Medicare and MA plans are similar, with MA plans incentivizing better resource utilization but tend to perform worse in access and patient satisfaction.2,3 To our knowledge, the most recent review was largely based on data from more than a decade ago.3 In this paper, we focus on evidence published since 2010 as well as recent practice innovations in the healthcare market.

History of Medicare

Overview of benefits & coverage

Medicare was created in 1965 as a U.S. federal insurance program to cover the cost of healthcare services for the people aged 65 and older. Under the Social Security Amendments of 1972, this coverage was expanded to younger people with certain disabilities and anyone with end-stage renal disease needing dialysis or transplant. Originally, Medicare only included Part A which covered hospital services, and Part B which covered outpatient medical services. The 2003 Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) added Medicare Part D (the Medicare drug benefit) starting in 2006.4 These plans are fee-for-service insurance plans, with beneficiary premiums required for Part B and later for Part D. Together, the fee-for-service program is considered Traditional Medicare (TM).

Since the beginning, Medicare has also contracted with private plans such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs) such as Kaiser Permanente and the Health Insurance Plan of NY to provide coverage for enrollees.5,6 In 2003, the MMA renamed the private plan option from Medicare + Choice (M+C) to Medicare Advantage (MA).

Currently, Medicare has nearly 60 million enrollees, two-thirds of whom are covered by TM, and the remaining 34% are covered through Medicare Advantage.1 Today, Part A covers not only hospital stays but also certain types of long term services such as short-term skilled nursing facility stays, hospice, and home visits. Part B includes outpatient services and preventive care. Part C, or Medicare Advantage, includes all benefits within Parts A and B and often Part D, as well as additional non-Medicare benefits such as dental, fitness, and vision coverage. Medicare Advantage enrollment has doubled in the last decade from 10.5 million people in 2009 to 22 million people in 2019.1

Payment models & cost of care

Since 1966, Medicare has contracted with HMOs, which are individual networks of physicians and hospitals that provide service at a fixed monthly or annual payment, modeled after organizations such as the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan in California. In the beginning, these contracts were few due to the small number of HMOs and Medicare’s unattractive retrospective payment model.7 In the late 1970s to 1980s, though, there was a significant increase in the number of HMOs following the HMO Act of 1973 under President Nixon, which provided federal funding to catalyze the growth of this sector.

Setting the payment rate for Commercial health plans in Medicare has been a challenge over time. The 1982 Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) set prospective risk-based capitated payments at 95% adjusted average per capita cost (AAPCC) of traditional Medicare based on the county of residence and demographics of the enrollee with the concept that the Medicare program would share in the efficiencies of the commercial market.7,8 Unfortunately, this payment model created strong incentives to recruit enrollees heathier than traditional Medicare enrollees, a practice known as favorable selection or cream skimming. Because risk-adjustment mechanisms were inadequate at this time, Medicare was found to be paying more for the care of a patient through Medicare Advantage than under traditional Medicare.8

The Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997 adjusted payments rates for private Medicare plans in attempts to contain cost, increase access, and correct for favorable selection. The BBA established the Medicare + Choice program and payment floors for rural counties. It also included enrollees’ demographic status in Medicare’s payment rate adjustments for private plans. New plan options such as preferred provider organizations (PPOs), private fee-for-service (PFFS), and high-deductible plans were created.8 BBA changes to the payment rules slowed the growth of M+C plan payments and led to increased beneficiary premiums and reduced benefits. This financial model proved unattractive to many commercial health plans who left the market as a result.9

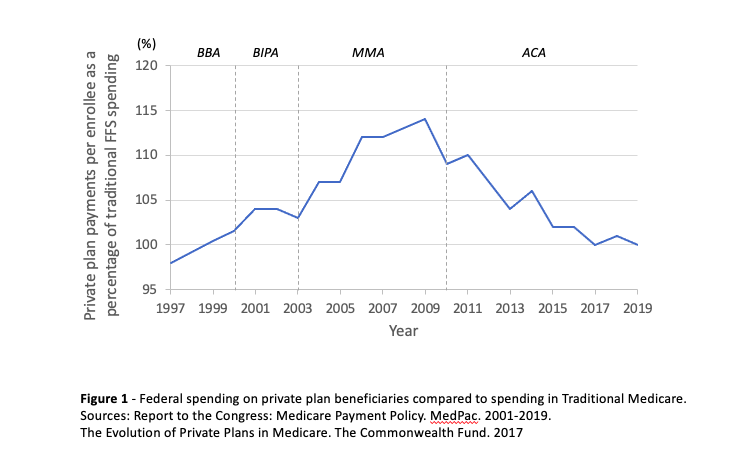

Adjustments have continued during the past two decades. In 2000, the Benefits Improvement and Protection Act (BIPA) raised the payment rates for private plans in both rural and urban counties and added diagnostic information to the risk adjustment models. In 2003, the MMA again raised payments and established a new bidding system in which private plans bid on the cost of delivering care for a county, and if the bid is lower than benchmark TM spending, the plan would receive a rebate that can be used to expand enrollee benefits.8 These various adjustments led to higher average per capita federal payments for enrollees in private plans. By 2009, payments to MA plans were as much as 14% higher than that for an equivalent enrollee in TM.10

The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), commonly known as Obamacare, took further steps to risk adjust for geography & enrollee health statuses in MA plans. Other changes included adjusting MA plans’ risk scores to account for increased coding intensity, and a new payment model where plans received bonuses based on quality.8,11 As a result of the ACA, payments to MA plans are now more aligned with TM spending, and MA enrollments have gradually increased. From 2017 to 2019, the per capita MA to TM payment ratios, after adjusting for risk and including quality bonuses, was close to 100% (Figure 1). However, MedPac estimates that if coding intensity had been fully considered beyond the 5.9% statutory rate, it would add another 1-2% to the relative MA payment rate.12

While federal spending is thought to be roughly equal by formula between the two models, a comparison of claims level data between several private MA plans and traditional Medicare found that actual per capita healthcare spending of enrollees in MA plans is much lower, largely due to lower utilization of services among MA enrollees.13 Enrollees in Medicare Advantage also tend to pay lower premiums than for traditional Medicare since they no longer need supplemental insurance and/or a separate prescription drug plans. Average premiums paid by MA enrollees was $29 per month in 2019, down from $44 per month in 2010,1 while the Part B premium is $144.6014 and part D premiums vary by plan in TM. Traditional Medicare does not have an out-of-pocket maximum as it is required for MA plans. However, little is known about the total out-of-pocket costs for enrollees in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage.11

Evidence on Quality, Outcomes and Utilization

In addition to reviewing information from CMS and the Kaiser Family Foundation on Medicare Advantage care quality and utilization patterns, we searched PubMed for comparative studies of MA and TM fee-for-service (FFS) using key words such as “Medicare Advantage”, “HMO”, “health maintenance organization”, “Medicare fee-for-service” or “traditional Medicare.” Regional or national studies published from 2010 to 2020 were included. Single-institutional studies or studies utilizing data from before 2000 were excluded. Commentaries or studies not relevant to quality, outcomes, or utilization of care were also excluded.

Overall, comparisons across studies are difficult due to differences in study designs, data sources, timing, and specific outcomes measured. With the exception of patience experience data captured through CAHPS, most of the studies we reviewed draw data from administrative claims or other types of secondary data which may limit characterization of the patient populations or services delivered to beneficiaries. Unlike HEDIS measurements collected for MA plans, TM claims data often do not enable direct measurement of quality. Analysis of large population samples are relatively overpowered, so even small effects are found to be statistically significant while clearly not achieving clinical significance.

Performance measures and outcomes

Each year, CMS attempts to measure the quality of services provided by Medicare Part C (MA) & Part D (prescription drugs) plans using the Star rating system. The ratings are on a scale of one to five, with a score of five being the highest quality rating. The Star ratings are calculated from clinical measures reported by the plans and patient experience data. For MA contracts that offer prescription drug plans (MA-PDs), 52% of the 210 contracts that will be offered in 2020 had a rating of 4.0 or higher, 82% of MA-PD enrollees are in such contracts currently.15 The ratings may not reflect the actual care received for a specific enrollee, as the MA contracts often draw enrollees from multiple geographic areas with varied levels of care quality.12

In general, the limited available evidence continues to suggest mixed results with respect to quality and patient outcomes between MA plans and TM. [Appendix Table 1] A number of studies have demonstrated higher performance on ambulatory and preventive care quality measures for MA plans compared to TM. These data include process measures such as disease screening and vaccination rates, as well as medication treatment adherence.16–20 Positive performance differences between MA and TM plans can be more pronounced in MA-HMO plans than for MA-PPO plans, suggesting the impact of better care coordination on these measures.20 In contrast, there is also some evidence that TM beneficiaries may be more likely to receive care from higher quality facilities or providers.21–23

While MA plans appear to be more successful at implementing preventive efforts, these successes sometimes do not directly translate into improved clinical outcomes. In a recent secondary prevention study, MA plan beneficiaries with coronary heart disease were slightly more likely than TM patients to receive secondary prevention treatments, but both populations achieved similar results in terms of blood pressure control and lipid management.24 Overall, studies comparing risk-adjusted mortality rates between TM and MA beneficiaries again show mixed results, and there is evidence that over time the mortality rates converge between patients in these two types of Medicare.25–27 Studies on differences in hospital readmission rates also vary and appear to be sensitive to risk adjustment methodologies, geography, and data sources.28–31

Based on data from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS), patient experiences across TM and MA plans are also mixed. There is evidence that MA patients tend to report more ease in getting medications and in getting information on cost and coverage, but TM may outperform MA in patient reported access to care.20,32 A longitudinal national study of Medicare beneficiaries from 2003-2009 suggested that MA patient ratings of their physicians are improving over time.16 In both MA and TM, higher intensity of care appears to be associated with worse care experiences, and patients with depressive symptoms tend to also have more negative experiences, and the differences may be larger in MA than in TM.33,34

Access and utilization

One major feature of MA plans is that they offer members more limited provider networks, although Medicare has implemented network adequacy requirements that all plans must meet. The Kaiser Family Foundation examined hospital network access for ~400 MA plans in 2015, it found that plan networks on average included roughly half of all hospitals in a given county. The range of narrow vs. broad networks varied significantly across MA plans, with the former including up to 30% of hospitals and the latter including 70% or more hospitals.35 In a follow up study of physician networks within MA plans, it was found that on average the plans included 46% of all physicians in a given county, and again the network size varied greatly. Across 26 medical specialties that MA plans are required to include, access to psychiatrists was the most restricted. Access to cardiothoracic surgeons, neurosurgeons, plastic surgeons, and radiation oncologists were also restricted for some plans.35

With respect to utilization, studies suggest that beneficiaries in MA plans tend to have more appropriate use of services than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare.36–40,18,41–44 Better utilization of resources is reflected in the lower rates of specific interventional procedures, fewer preventable hospitalizations, shorter lengths of stay in hospitals, as well as more efficient use of post-acute care services. [Appendix Table 2] At least three recent studies suggest that MA beneficiaries tend to have shorter rehabilitation stays with better outcomes.42–44

Innovative Care Delivery Models

Under the capitated payment model, MA plans are financially incentivized to find innovative ways of delivering better quality of care at lower cost. MA plans have the advantage of being able to implement new care models at scale across providers and geographic areas. TM has also implemented novel payment models such as Accountable Care Organizations, Primary Care Transformation, and Episode-based Payment Initiatives, though these models largely rely on individual provider organizations for design and execution of care models within the program constraints.

Recently, the increase in MA enrollment has spawned the growth of a number of new primary care provider models focused on improving care for the elderly and/or high-risk populations under fully capitated payment arrangements. These programs often feature integrated team-based care and use custom technology for health records, decision support and care management. Several have experimented with physician panel sizes related to patient acuity, with the mix of providers on the clinical team, and with ways in which technology can support the overall care goals of the organization.

Many of these new models have demonstrated clinical improvements in their target population. ChenMed is an example of a high-touch primary care center for seniors that has been able to lower per member per month spending and hospital admission rates.45 Iora Health is another rapidly growing network of primary care clinics that targets the Medicare population, and it has reported better hypertension and diabetes control, and reduced hospital admissions and ER visits for their patients.46 Oak Street Health provides care for Medicare, Medicaid, and dual-eligible patient, and despite having a panel of clinically and socially complex patients, Oak Street reported large reductions in hospital admission rates, ER visits, and 30-day readmission rates.47 CareMore, which is now an integrated health delivery system under Anthem, grew out of a novel care model targeting high-risk populations in the early 90s and became a MA program by 1997, reported that it has been able to lower hospital and skilled nursing facility utilizations, 30-day hospital readmissions, and provide care at a lower cost than other MA plans.48 Another example of a fast-growing MA company is Devoted Health. Its model is built upon technology-enabled decision making as well as partnerships with existing care providers, but it also has its own in-house care coordination and care delivery teams that focus on the highest risk populations.49

Looking Forward

In the past, payment rules resulted in Medicare overspending on patients enrolled in MA compared to TM. This risk of overpayment has been reduced, but not eliminated, due to implementation of more sophisticated risk-adjustment mechanisms and increased accountability for quality. CMS now spends a near equal amount for enrollees in TM and FFS, and there is evidence that the cost of care delivery in MA plans are less than in TM. At least some of these savings are passed on to MA enrollees as lower premiums and out-of-pocket costs. In sum, recent comparative data on quality, outcomes, and utilization remain largely unchanged since previous reviews.

The growth of MA is partially a reflection of the market competitiveness of private health plans based on the perception of value by consumers. Many MA plans have developed and recently introduced innovative care delivery models. While there is early evidence of success of some of these models, whether they can maintain their performance as they scale remains an important question for further research.

Appendix

| Author | Publication Year | Category | Data Year(s) | Geography | Data Sources | Sample size | Outcomes of Interest | Direction of positive outcome |

| Huesch21 | 2010 | Quality | 2003-2006 | Regional | Florida Department of Health’s Agency for Health Care Administration | 33,840 FFS, 6,626 MA patients | Quality of physicians used by Florida coronary stent patients | FFS |

| Brennan et al.50 | 2010 | Quality | 2006-2007 | National | HEDIS | 35,176,538 – 34,842,196 FFS and 5,978,584 -6,454,358 MA beneficiaries | 11 Quality measures (med management, breast cancer & CAD screening, diabetes care) | Neutral or Mixed |

| Ayanian et al.17 | 2013 | Quality | 2009 | National | Medicare Beneficiary Summary File, HEDIS, claims data | 453,820 FFS patients and 495,836 MA-HMOs patients, 81,480 MA-PPOs patients | Mammography screening among racial/ethnic groups | MA |

| Hung et al.19 | 2016 | Quality | 2009 | National | Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) data | 5,417 FFS beneficiaries and 1,875 MA beneficiaries | Mammography screening for beneficiaries | MA |

| Chang et al.51 | 2016 | Quality | 2011 | National | CMS beneficiary enrollment files, quarterly long-term care MDS files | 1,800,193 FFS patients and 371,641 MA patients | Nursing home quality | Neutral or Mixed |

| Meyers et al.22 | 2018 | Quality | 2012-2014 | National | MBSF, MDS, HEDIS, Online Survey Certification and Reporting System (OSCAR) for SNF-level characteristics | 3,335,476 FFS and 1,248646 MA patients | Quality of skilled nursing facilities entered by beneficiaries | FFS |

| Gidwani-Marszowski et al.52 | 2018 | Quality | 2008-2013 | National | VHA and Medicare administrative data | 295,605 FFS and 1,172,230 MA decedents | Hospice care & hospice duration for veterans | MA |

| Teno et al.53 | 2018 | Quality | 2000, 2005, 2009, 2011, 2015 | National | Medicare enrollment and claims data, MDS, MBSF | 1,361,870 FFS and 871,845 MA decedents | Site of death, place of care, and care transitions during last 3 days of life | Neutral or Mixed |

| Schwartz et al.23 | 2019 | Quality | 2015 | National | Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS), MBSF | 3,316,163 FFS and 1,075,817 MA patients | Quality of home health agencies used, based on patient care star ratings | FFS |

| Meyers et al.54 | 2020 | Quality | 2012-2016 | National | Medicare Provider and Analysis Review (MedPAR) | 5,059,508 TM and 2,071,102 MA patients | Quality of hospitals enrollees enter, as measured by star ratings | Neutral or Mixed |

| Li et. al.30 | 2016 | Quality and Outcome | 2009-2012 | Regional | HCUP New York State Inpatient Databases | 64,357 total patients in 2009 to 56,445 in 2012 | 30-day readmission rates and racial disparity for AMI, CHF, or pneumonia in New York | MA |

| Rivera-Hernandez et al.55 | 2019 | Quality and Outcome | 2015 | National | MDS, MBSF, Long-Term Care: Facts on Care in the United States and Nursing Home Compare Five-Star Ratings database, U.S. Census | 1,291,133 FFS patients and 522,830 MA patients | Racial disparity in 30 -day readmission rate in SNFs | Neutral or Mixed |

| Friedman et al.25 | 2010 | Outcome | 2006 | Regional | HCUP-SID | 3,478,947 FFS and 670,019 MA discharges | Risk-adjusted mortality rates and postoperative safety event rates in 13 states | Neutral or Mixed |

| Ward et al.56 | 2010 | Outcome | 2005-2007 | National | The National Cancer Database | 843,177 Total patients | Relationship between stage of diagnosis and insurance status for eight types of cancer | MA |

| Lemieux et al.29 | 2012 | Outcome | 2006-2008 | National | MedAssurant Medical Outcomes Research for Effectiveness and Economics Registry, Medicare 5% sample files | 812,869 FFS and 907,704 MA patients | 30-day medical and surgical readmission rates | MA |

| Friedman et al.28 | 2012 | Outcome | 2006 | Regional | HCUP-SID | 870,335 FFS and 266,577 MA discharges | Likelihood of readmission after hospital discharge in five states | FFS |

| Basu et al.57 | 2013 | Outcome | 2002 | Regional | HCUP-SID | 2,971,673 FFS, 509,413 MA patients | Adverse events during hospitalization in Florida | FFS |

| Beveridge et al.26 | 2017 | Outcome | 2010-2013 | National | MA claims data, 5% randomly selected Limited Data Set samples from the CMS for 2010-2012 | 4,313,885 person-years FFS and 5,477,976 person-years MA | Mortality rate of beneficiaries | MA |

| Newhouse et al.27 | 2019 | Outcome | 2007-2017 | National | MBSF | Unavailable | Mortality rate of beneficiaries over time | Neutral or Mixed |

| Figueroa et al.24 | 2019 | Outcome | 2013-2014 | National | Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence (PINNACLE) registry | 172,732 FFS and 35,563 MA patients | CAD secondary prevention treatment and intermediate outcomes | Neutral or Mixed |

| Panagiotou et al.31 | 2019 | Outcome | 2011-2014 | National | HEDIS, Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) | 4,159,840 FFS and 1,218,236 MA discharges | 30 -day hospital readmissions for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia patients | FFS |

| Mittler et al.33 | 2010 | Care Experience | 2003 | National | CAHPS | 120,974 FFS and 135,757 MA beneficiaries | Patient care experiences based on market service intensity | FFS |

| Elliot et al.32 | 2011 | Care Experience | 2007 | National | CAHPS | 201,444 FFS and 132,937 MA beneficiaries | 11 measures of patient experience with care | Neutral or Mixed |

| Martino et al.34 | 2016 | Care Experience | 2010 | National | CAHPS | 135,874 FFS and 220,040 MA beneficiaries | Disparities in care between patients with depressive symptoms and those without | FFS |

| Ayanian et al.15 | 2013 | Quality and Care Experience | 2003-2009 | National | HEDIS, CAHPS, MBSF | Clinical quality: 742,976 MA-HMO enrollees, comparable number of FFS enrollees. Patient experience: 103,254 FFS and 128,706 MA-HMO enrollees | Ambulatory care quality and patient experience | MA |

| Timbie et al.20 | 2017 | Quality and Care Experience | 2010-2012 | Regional | HEDIS, Part D measures, MCAHPS, claims data | 6,352,239 FFS and 3,571,743 MA beneficiaries | Clinical quality measures & patient experience measures among beneficiaries in CA, NY, and FL | MA |

Appendix Table 1: Studies comparing MA and TM fee-for-service (FFS) on quality, outcomes, care experience.

Notes: CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

HCUP-SID = AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases

MBSF = Master Beneficiary Summary File

MDS = Minimum Data Set

| Author | Publication Year | Category | Data Year(s) | Geography | Data Sources | Sample size | Outcomes of Interest | Direction of positive outcome |

| Basu et al.36 | 2012 | Utilization | 2004 | Regional | AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP-SID) | 936,698 Total admissions | Preventable and referral-sensitive hospitalizations in NY, FL, CA | MA |

| Landon et al37 | 2012 | Utilization | 2003-2009 | National | HEDIS, CAHPS, Medicare Beneficiary Summary files | 103,162-152,444 FFS and 66,813-131104 for MA | Service utilization for surgical procedures, ambulatory care, and inpatient care | MA |

| Stevenson et al.38 | 2013 | Utilization | 2003-2009 | National | Medicare Beneficiary Summary File, HEDIS, claims data | 206,754 FFS patients in 2003 to 189,721 in 2009; 150,679 MA patients in 2003 – 248,676 in 2009 | End-of-life service use | MA |

| Nicholas LH 39 | 2013 | Utilization | 1999-2005 | Regional | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases (SID) matched to Medicare enrollment data | >1,500 MA enrollees and 5,000 FFS | Rates of hospitalizations in Arizona, Florida, New Jersey and New York | MA |

| Matlock et al.58 | 2013 | Utilization | 2003-2007 | Regional | Medicare Enrollment Database; Administrative, claims, and clinical electronic health record data from the Cardiovascular Research Network | 5,013,650 FFS and 878,339 MA patients | Rates of coronary angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) | Neutral or Mixed |

| Raetzman et al.40 | 2015 | Utilization | 2013 | Regional | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) State Inpatient Databases (SID) for 13 States | 4,165,200 FFS and 1,650,200 MA hospital stays | Hospital lengths of stay | MA |

| Landon et al.18 | 2015 | Utilization and Quality | 2007 | National | Medicare Beneficiary Summary files, HEDIS, claims data | 4,207,433 MA-HMO enrollees, 318,293 MA-PPO enrollees, matched to FFS | Utilization and quality of ambulatory care for diabetes and cardiovascular disease patients | MA |

| Waxman et al.41 | 2016 | Utilization | 2010-2011 | National | CMS OASIS file, American Community Survey | 30,837,130 FFS and 10,594,658 MA beneficiaries | Proportin of beneficiaries receiving home health and duration of use | MA |

| Huckfeldt et al.42 | 2017 | Utilization and Outcome | 2011-2013 | National | Medicare Provider Analysis & Review File, Master Beneficiary Summary File, Minimum Data Set, Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Patient Assessment Instrument | 1,630,214 FFS and 582,024 MA care episodes | Post-acute care utilization for patients with lower extremity joint replacement, stroke, and heart failure | MA |

| Henke et al.59 | 2018 | Utilization | 2013 | Regional | HCUP State Inpatient Databases, AHA Annual Survey data, Medicare Enrollment Denominator File | 1,926,712 MA and 5,907,956 TM discharges | length of stay and cost per hospital discharge | Neutral or Mixed |

| Li et al.60 | 2018 | Utilization | 2007-13 | National | Medicare claims data, HEDIS, Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS), Minimum Data Set, Medicare beneficiary summary file | 54,000,000 total Medicare beneficiaries | Geographic variations in the use of home health, SNF, and hospital care between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. | Neutral or Mixed |

| Kumar et al.43 | 2018 | Utilization and Outcome | 2011-2015 | National | Master Beneficiary Summary File, Medicare Provider and Analysis Review data, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set data, the Minimum Data Set, and the American Community Survey | 211,296 FFS and 75,554 MA patients | Rehabilitation service use, length of stay, and outcomes in hip fracture patients | MA |

Appendix Table 2 – Studies comparing MA and TM fee-for-service (FFS) on utilization, including some studies examining both utilization and outcome or utilization and quality.

Notes: CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

HEDIS = Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

HCUP-SID = AHRQ’s Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases

MBSF = Master Beneficiary Summary File

MDS = Minimum Data Set

Acknowledgement

We want to thank our research assistant Sohini Guin for help in proofreading the appendix summary tables.

References

(Note references 50-60 are for appendix tables only)

- Medicare Advantage. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019. Accessed January 9, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-advantage/

- Miller RH, Luft HS. HMO Plan Performance Update: An Analysis Of The Literature, 1997–2001. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(4):63-86. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.63

- Gold M, Casillas G. What Do We Know About Health Care Access and Quality in Medicare Advantage Versus the Traditional Medicare Program? Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/what-do-we-know-about-health-care-access-and-quality-in-medicare-advantage-versus-the-traditional-medicare-program/

- An Overview of Medicare.; 2019. Accessed January 9, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/an-overview-of-medicare/

- Celebrating 50 years of Medicare. Accessed June 18, 2020. https://about.kaiserpermanente.org/our-story/our-history/celebrating-50-years-of-medicare

- EmblemHealth Medicare Plan Receives Four Stars for Quality | EmblemHealth. Accessed June 18, 2020. https://www.emblemhealth.com/news/press-releases/emblemhealth-medicare-plan-receives-four-stars-for-quality

- Gruber LR, Shadle M, Polich C. From Movement To Industry: The Growth Of HMOs | Health Affairs. Accessed January 9, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.7.3.197

- The Evolution of Private Plans in Medicare. Accessed January 9, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/dec/evolution-private-plans-medicare

- Gold M. Can Managed Care And Competition Control Medicare Costs? Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(Suppl1):W3-176. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.W3.176

- Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2009.

- Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare Advantage Checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163-2172. doi:10.1056/NEJMhpr1804089

- Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2019. http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar19_medpac_ch13_sec.pdf

- Curto V, Einav L, Finkelstein A, Levin JD, Bhattacharya J. Healthcare Spending and Utilization in Public and Private Medicare. Published online January 2017. doi:10.3386/w23090

- Medicare costs at a glance | Medicare. Accessed June 18, 2020. https://www.medicare.gov/your-medicare-costs/medicare-costs-at-a-glance

- Fact Sheet – 2020 Part C and D Star Rating. CMS; 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/Downloads/2020-Star-Ratings-Fact-Sheet-.pdf

- Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Saunders RC, Pawlson LG, Newhouse JP. Medicare Beneficiaries More Likely To Receive Appropriate Ambulatory Services In HMOs Than In Traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1228-1235. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0773

- Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Newhouse JP. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Use of Mammography Between Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(24):1891-1896. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt333

- Landon BE, Zaslavsky AM, Saunders R, Pawlson LG, Newhouse JP, Ayanian JZ. A Comparison of Relative Resource Use and Quality in Medicare Advantage Health Plans Versus Traditional Medicare. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(8):559-566.

- Hung A, Stuart B, Harris I. The Effect of Medicare Advantage Enrollment on Mammographic Screening. AJMC. Published online January 2016. Accessed May 12, 2020. https://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2016/2016-vol22-n2/the-effect-of-medicare-advantage-enrollment-on-mammographic-screening

- Timbie JW, Bogart A, Damberg CL, et al. Medicare Advantage and Fee-for-Service Performance on Clinical Quality and Patient Experience Measures: Comparisons from Three Large States. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(6):2038-2060. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12787

- Huesch MD. Managing Care? Medicare Managed Care and Patient Use of Cardiologists. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(2):329-354. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01070.x

- Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M. Medicare Advantage Enrollees More Likely To Enter Lower-Quality Nursing Homes Compared To Fee-For-Service Enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):78-85. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0714

- Schwartz ML, Kosar CM, Mroz TM, Kumar A, Rahman M. Quality of Home Health Agencies Serving Traditional Medicare vs Medicare Advantage Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9). doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10622

- Figueroa JF, Blumenthal DM, Feyman Y, et al. Differences in Management of Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With Medicare Advantage vs Traditional Fee-for-Service Medicare Among Cardiology Practices. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(3):265-271. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.0007

- Friedman B, Jiang HJ. Do Medicare Advantage enrollees tend to be admitted to hospitals with better or worse outcomes compared with fee-for-service enrollees? Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2010;10(2):171-185. doi:10.1007/s10754-010-9076-0

- Beveridge R, Mendes S, Caplan A, et al. Mortality Differences Between Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage: A Risk-Adjusted Assessment Using Claims Data. Inq J Health Care Organ Provis Financ. 2017;54.

- Newhouse JP, Price M, McWilliams JM, Hsu J, Souza J, Landon BE. Adjusted Mortality Rates Are Lower For Medicare Advantage Than Traditional Medicare, But The Rates Converge Over Time |. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(4). Accessed April 6, 2020. https://www-healthaffairs-org.stanford.idm.oclc.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05390

- Friedman B, Jiang HJ, Steiner C, Bott J. Likelihood of Hospital Readmission after First Discharge: Medicare Advantage vs. Fee-for-Service Patients. Inquiry. 2012;49:202-213.

- Lemieux J, Sennett C, Wang R, Mulligan T, Bumbaugh J. Hospital readmission rates in Medicare Advantage plans. – PubMed – NCBI. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(2):96-104.

- Li Y, Cen X, Cai X, Wang D, Thirukumaran CP, Glance LG. Does Medicare Advantage Reduce Racial Disparity in 30-Day Rehospitalization for Medicare Beneficiaries?: Med Care Res Rev. Published online December 6, 2016. doi:10.1177/1077558716681938

- Panagiotou OA, Kumar A, Gutman R, et al. Hospital Readmission Rates in Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare: A Retrospective Population-Based Analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(2):99-106. doi:10.7326/M18-1795

- Elliott MN, Haviland AM, Orr N, Hambarsoomian K, Cleary PD. How do the experiences of Medicare beneficiary subgroups differ between managed care and original Medicare? Health Serv Res. 2011;46(4):1039-1058. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01245.x

- Mittler JN, Landon BE, Fisher ES, Cleary PD, Zaslavsky AM. Market Variations in Intensity of Medicare Service Use and Beneficiary Experiences with Care. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(3):647-669. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01108.x

- Martino SC, Elliott MN, Haviland AM, Saliba D, Burkhart Q, Kanouse DE. Comparing the Health Care Experiences of Medicare Beneficiaries with and without Depressive Symptoms in Medicare Managed Care versus Fee‐for‐Service. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(3):1002-1020. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12359

- Jacobson G, Rae M, Neuman T, Orgera K, Boccuti C. Medicare Advantage: How Robust Are Plans’ Physician Networks? The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Published October 5, 2017. Accessed January 9, 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicare/report/medicare-advantage-how-robust-are-plans-physician-networks/

- Basu J, Mobley LR. Medicare Managed Care plan Performance: A Comparison across Hospitalization Types. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2012;2(1). doi:10.5600/mmrr.002.01.a02

- Landon B, Zaslavsky A, Saunders R, Pawlson L, Newhouse J, Ayanian J. Utilization of Services in Medicare Advantage versus Traditional Medicare since the Passage of the Medicare Modernization Act. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2012;31(12):2609-2617. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0179

- Stevenson DG, Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Newhouse JP, Landon BE. Service Use at the End of Life in Medicare Advantage versus Traditional Medicare. Med Care. 2013;51(10):931-937. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a50278

- Nicholas LH. Better Quality of Care or Healthier Patients? Hospital Utilization by Medicare Advantage and Fee-for-Service Enrollees. Forum Health Econ Policy. 2013;16(1):137-161. doi:10.1515/fhep-2012-0037

- Raetzman SO, Hines AL, Barrett ML, Karaca Z. Hospital Stays in Medicare Advantage Plans Versus the Traditional Medicare Fee-for-Service Program, 2013. Healthc Cost Util Proj HCUP Stat Briefs. Published online 2015. Accessed April 14, 2020. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK343514/

- Waxman D, Min L, Setodji C, et al. Does Medicare Advantage Enrollment Affect Home Healthcare Use? AJMC. 2016;22(11):714-720.

- Huckfeldt PJ, Escarce JJ, Rabideau B, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Less Intense Postacute Care, Better Outcomes For Enrollees In Medicare Advantage Than Those In Fee-For-Service. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):91-100. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1027

- Kumar A, Rahman M, Trivedi AN, Resnik L, Gozalo P, Mor V. Comparing post-acute rehabilitation use, length of stay, and outcomes experienced by Medicare fee-for-service and Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with hip fracture in the United States: A secondary analysis of administrative data. PLoS Med. 2018;15(6):e1002592. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002592

- Cao Y, Nie J, Sisto SA, Niewczyk P, Noyes K. Assessment of Differences in Inpatient Rehabilitation Services for Length of Stay and Health Outcomes Between US Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e201204-e201204. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1204

- Ghany R, Tamariz L, Chen G, et al. High-touch care leads to better outcomes and lower costs in a senior population. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(9):e300-e304.

- Iora Health. Iora Health. Accessed January 10, 2020. https://www.iorahealth.com/real-results/

- Medicare-only Oak Street Health isn’t shy about taking big risks. American Medical Association. Accessed January 9, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/payment-delivery-models/medicare-only-oak-street-health-isn-t-shy-about-taking

- CareMore Improve Outcomes High-Needs Patients. Accessed June 23, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/case-study/2017/mar/caremore-improving-outcomes-and-controlling-health-care-spending

- Park E. Why Devoted Health. Medium. Published October 16, 2018. Accessed June 24, 2020. https://medium.com/@edparkdevoted/why-devoted-health-576516ce64e2

- Brennan N, Shepard M. Comparing Quality of Care in the Medicare Program. AJMC. Published online November 2010. Accessed January 9, 2020. https://www.ajmc.com/journals/issue/2010/2010-11-vol16-n11/ajmc_10nov_brennan841to848

- Chang E, Ruder T, Setodji C, et al. Differences in Nursing Home Quality Between Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare Patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(10):960.e9-960.e14. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2016.07.017

- Gidwani‐Marszowski R, Kinosian B, Scott W, Phibbs CS, Intrator O. Hospice Care of Veterans in Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare: A Risk-Adjusted Analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(8):1508-1514. doi:10.1111/jgs.15434

- Teno JM, Gozalo P, Trivedi AN, et al. Site of Death, Place of Care, and Health Care Transitions Among US Medicare Beneficiaries, 2000-2015. JAMA. 2018;320(3):264-271. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8981

- Meyers DJ, Trivedi AN, Mor V, Rahman M. Comparison of the Quality of Hospitals That Admit Medicare Advantage Patients vs Traditional Medicare Patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1). doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19310

- Rivera-Hernandez M, Rahman M, Mor V, Trivedi AN. Racial Disparities in Readmission Rates among Patients Discharged to Skilled Nursing Facilities – Rivera‐Hernandez – 2019 – Journal of the American Geriatrics Society – Wiley Online Library. 2019;67(8):1672-1679.

- Ward EM, Fedewa SA, Cokkinides V, Virgo K. The association of insurance and stage at diagnosis among patients aged 55 to 74 years in the national cancer database. Cancer J Sudbury Mass. 2010;16(6):614-621. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181ff2aec

- Basu J, Friedman B. Adverse events for hospitalized medicare patients: is there a difference between HMO and FFS enrollees? Soc Work Public Health. 2013;28(7):639-651. doi:10.1080/19371918.2011.592089

- Matlock DD, Groeneveld PW, Sidney S, et al. Geographic Variation in Cardiovascular Procedures: Medicare Fee-For-Service versus Medicare Advantage. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310(2):155-162. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.7837

- Henke RM, Karaca Z, Gibson TB, et al. Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare Hospitalization Intensity and Readmissions. Med Care Res Rev. 2018;75(4):434-453. doi:10.1177/1077558717692103

- Li Q, Rahman M, Gozalo P, Keohane LM, Gold MR, Trivedi AN. Regional Variations: The Use Of Hospitals, Home Health, And Skilled Nursing In Traditional Medicare And Medicare Advantage. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2018;37(8):1274-1281. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0147

Addendum to A Narrative Review of Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage

Since the publication of our review, there has been a growing debate over the true cost of Medicare Advantage. While CMS payments to MA plans have been lower in the last decade, MedPac continues to estimate that the per capita payments for MA enrollees are higher than Traditional Medicare when coding intensity is considered. Critics have pointed out that this higher intensity of coding underlies the business model of many MA plans, and it is the reason for the rapid growth and the outsized investments into health plans and primary care startups that focus on the MA population.[1]

Profits resulting from upcoding allow for the lowered premiums and more comprehensive enrollee benefits, but much of the profits also remain with the investors and commercial entities at a high cost to CMS and to taxpayers. Furthermore, the launch of Direct Contracting Entities (DCEs), which enables varying degrees of capitated pay-for-performance payments in organizations that served Traditional Medicare enrollees, allows the MA plans to bring the same coding practices into the fee-for-service Medicare market and threatens the growth of Accountable Care Organizations (although the ACO program has other issues affecting growth).[2]

Access to medically necessary care under MA is also under scrutiny. A recent report from the Office of Inspector General (OIG) found that some MA organizations have denied beneficiary requests that fell within Medicare coverage rules. In reviewing a random sample of hundreds of denied prior authorization and payment requests, the OIG reported that some of the unnecessary denials stemmed from applying clinical criteria outside of Medicare coverage rules, which most frequently affected imaging, post-acute care, and injection services. Other denials and delays were due to requesting additional documentation even when records are sufficient, and from making either human or system review errors.[3]

Counter arguments contend that there remains evidence that MA costs are lower, that precise risk adjustments in MA plans are necessary for performance tracking, and that DCEs enable primary care providers to deliver more coordinated and better-quality care under performance-based contracting (although without providing evidence that the quality improvement is occurring in these models).[4] They emphasize that enrollees in MA plans are often of lower socioeconomic status, and the focus on quality led to innovative solutions for these higher risk

[1] Medicare Advantage, Direct Contracting, And The Medicare ‘Money Machine,’ Part 1: The Risk-Score Game. Sept 29, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210927.6239

[2] Medicare Advantage, Direct Contracting, And The Medicare ‘Money Machine,’ Part 2: Building On The ACO Model. Sept. 30, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210928.795755/full/

[3] Some Medicare Advantage Organization Denials of Prior Authorization Requests Raise Concerns About Beneficiary Access to Medically Necessary Care. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/OEI-09-18-00260.pdf

[4] The Important Roles Of Medicare Advantage And Direct Contracting: A Response To Gilfillan And Berwick. Feb 7, 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20220203.915914/