Thomas Rice, Department of Health Policy and Management, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health

Contact: trice@ucla.edu

Abstract

What is the message? The author summarizes key messages from his recent book, comparing the U.S. to multiple metrics of healthcare efficiency, access, and equity. The article discusses the sources of superior performance in other countries and suggests possible avenues for improvement in the U.S.

What is the evidence? Analysis and interpretation of publicly available data from multiple sources.

Acknowledgments: No acknowledgments, support, conflicts of interest, or disclaimers

Timeline: Submitted: June 21, 2021; Accepted after review: November 6, 2021

Cite as: Thomas Rice. Building A Better Health Insurance System: How The U.S. Can Benefit From The Experiences Of Other Countries. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.HMPI.org), Volume 6, Issue 2.

The U.S. Health Care System Needs To Learn From Other Countries

The U.S. health care system presents an example of massive inefficiency and unconscionable inequity. Per capita health care spending is twice that of most other high-income countries. What do we get for that extra spending? Not better health outcomes or even more services, but instead, sky-high unit prices. And those prices, coupled with a health insurance system riddled with gaps in coverage, creates such massive inequities that, during a one-year period, half of people in the bottom half of the income distribution had to skimp on care.

In putting together proposals to address these shortcomings, the policy community generally looks within the U.S. rather than to the outside. The one counterexample are single-payer proponents who suggest that we look north, but Canada has major problems of its own: long waits for some services, a meager benefits package that does not even include drug coverage for adults, and organizational and managerial stasis. I do not mean to pick on Canada, which spends far less than we do, has fewer access problems, and in general experiences comparable or better health outcomes. Rather, I wish to point out that there are a bevy of other countries that we ought to examine, several of which have found ways to perform better than we do. What can we learn from them?

To address this, I recently wrote a book, Health Insurance Systems: An International Comparison[1], that provides detailed descriptions of many aspects of several national health insurance systems and compares their performance with regard to efficiency and equity. The ten countries covered are Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. This article begins with cross-national data on how the U.S performs compared to the other nine countries. It then explains some of the reasons why other countries continue to perform far better. It concludes with a discussion of types of reform that are most feasible, recognizing that major changes to a $4 trillion industry are exceedingly difficult to achieve.

U.S. Performance Lags Badly On All Fronts

Efficiency

Spending

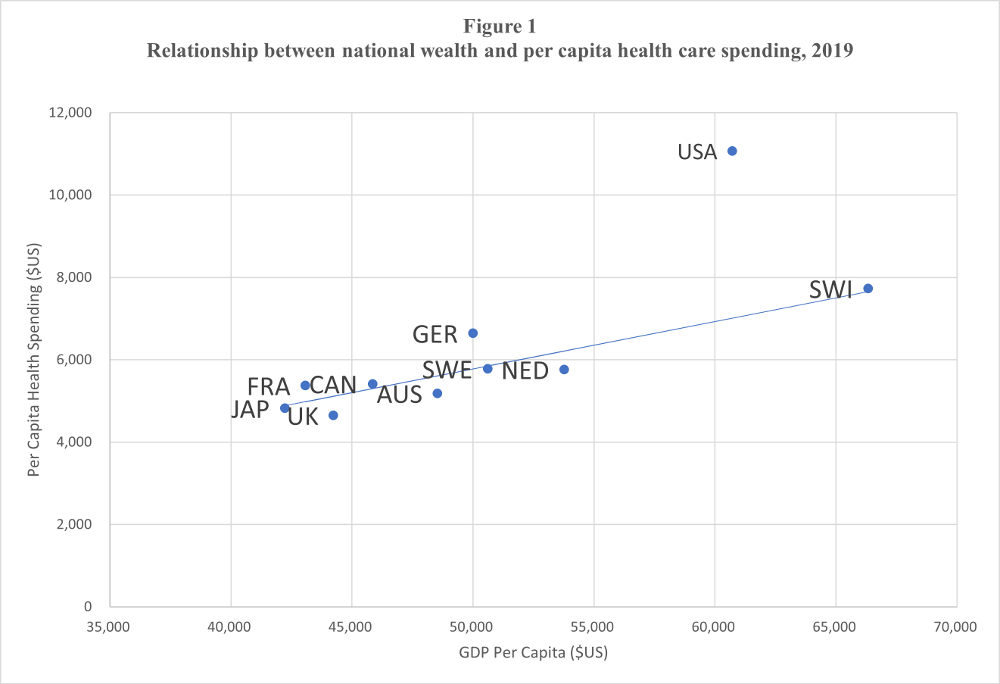

Think of efficiency as how much desirable output is achieved in relation to resources expended. Beginning with resource expenditure, there is a remarkably high correlation between how wealthy a country is and how much it spends on health care – for all of the counties except the United States. In Figure 1, the horizontal axis defines national wealth as GDP per capita; the vertical axis defines spending as per capita health expenditures adjusted for purchasing power. A simple trend line closely follows the points for nine countries other than the U.S.

Each country falls almost exactly on the line, meaning that if you know just one thing about these countries – how wealthy they are – you can get a good idea of how much they spend on health care. The outlier is the U.S., which spends about 40% more than would be predicted by its wealth. We will address some of the reasons why this is the case below.

The trend line is based on data from all countries except the United States.

Sources: From the book, Health Insurance Systems: An International Comparison, by Thomas Rice, published 2021 by Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. Original data from: OECD Health Statistics 2020 (https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm)

Mortality

Given the level of spending, for the U.S. system to be as efficient as other countries, it would have to produce much superior results – but the opposite is the case. One chapter of the book examines dozens of outcomes related to mortality, other health outcomes, affordability, waiting times, use of care, and satisfaction with each of the health care systems. The particular measures were chosen because one can argue that they are strongly affected by the health care system. Life expectancy is an example of a metric that is not included because other factors such as health behaviors are probably more important determinants than health system factors. The most common measure of how a health system affects mortality is a statistic called “mortality amenable to health care.” It measures the deaths that should be averted by a well-functioning health care system – roughly 30 diseases one should not die from, in most cases before the age of 75.[2] The U.S. rate, 88 per 100,000, is by far the highest (the U.K. is second highest at 69), 60% higher than the median of the other nine countries, and more than double the Swiss rate. One mortality statistic where the U.S. does excel is breast cancer, although it is more in the middle of the pack for other cancers.

Other Health Outcomes

It is harder to find comparable cross-national data on other health outcomes that one can confidently believe are mainly the responsibility of the health care system. Nonetheless, one statistic that is available for all of the countries except Japan is whether a person believes they experienced a medical, medication, or lab mistake in the last two years. Americans were most likely to claim that this had occurred, 19% citing that one of these mishaps occurred. This rate is more than double the rates expressed by the Germans and the French.

Access

A critical component of access is affordability. Even though the U.S. had the second highest per capita GDP after Switzerland, in every measure of affordability the U.S. ranked worst or second worst. Americans were:[3]

- Most likely to forgo medical care because of cost

- Most likely to forgo dental care because of cost

- Most likely to say that their insurance denied payment or paid less than expected

- Second most likely to say they had problems paying bills

- Second most likely to spend $1,000 out-of-pocket during the year

One often hears that a virtue of the U.S. system is that one does not have to wait to get care. It turns out that this is more nuanced than one might have guessed. Table 1 provides data across nine of the countries (all except Japan) for five measures of waiting: seeing a doctor or nurse the same or next day, having difficulty obtaining after-hours care, waiting two or more hours in the emergency room, waiting two or more months for a specialist appointment, and waiting four or more months for elective or nonemergency surgery. The only measures where U.S. performance is relatively good are shorter waits for specialist appointments and elective/nonemergency surgery. Still, Germany and France performed better on these indicators and the Netherlands, about the same as the U.S.

Table 1: Self-reported Waiting Times, 2016

| Country | Saw doctor or nurse on same or next day, last time needed medical care | Somewhat or very difficult to obtain after-hours care | Waited 2+ hours for care in emergency room | Waited 2+ months for specialist appointment | Waited 4+ months for elective/non-emergency surgery |

| Australia | 67% | 44% | 23% | 13% | 8% |

| Canada | 43% | 63% | 50% | 30% | 18% |

| France | 56% | 64% | 9% | 4% | 2% |

| Germany | 53% | 64% | 18% | 3% | 0% |

| Netherlands | 77% | 25% | 20% | 7% | 4% |

| Sweden | 49% | 64% | 39% | 19% | 12% |

| Switzerland | 57% | 58% | 26% | 9% | 7% |

| United Kingdom | 57% | 49% | 32% | 19% | 12% |

| United States | 51% | 51% | 25% | 6% | 4% |

Sources:

- From the book, Health Insurance Systems: An International Comparison, by Thomas Rice, published 2021 by Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Original data from: Commonwealth Fund. Mirror, mirror 2017: international comparisons reflects flaws and opportunities for better U.S. health. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2017_jul_schneider_mirror_mirror_2017.pdf Appendix 3, under Timeliness.

Utilization

Given our higher spending, one would expect that Americans would be receiving more care. Generally, this is not the case, as we use doctors and hospitals less, on average, than do people in the other countries. In fact, only the Swedes go to the doctor less. We do get more diagnostic scans than in other countries, ranking third of nine countries for MRIs and first for CT scans. Americans also are most likely to have bypass surgery, but second-to-last in receiving angioplasty.

Satisfaction

While satisfaction is obviously a subjective measure and could be affected by cross-national cultural differences, it is a critical measure of performance: preferences matter! As Table 2 shows, Americans are by far the least satisfied with their health care system among the nine countries where this question was asked. The 19% who think the system works pretty well, needing only minor changes, is by far the lowest, and but one-third as high as in Germany and Switzerland. And the 23% that say the system has so much wrong and needs to be completely rebuilt dwarfs all other countries, which are all in single digits.

Table 2: Satisfaction with Health Care System, 2016

| Country | System works pretty well, only minor changes necessary

[1] |

Some good things, but fundamental changes are needed

[2] |

System has so much wrong that it needs to be completely rebuilt

[3] |

| Australia | 44% | 46% | 4% |

| Canada | 35% | 55% | 9% |

| France | 54% | 41% | 4% |

| Germany | 60% | 37% | 3% |

| Netherlands | 43% | 46% | 8% |

| Sweden | 31% | 58% | 8% |

| Switzerland | 58% | 37% | 3% |

| United Kingdom | 44% | 46% | 7% |

| United States | 19% | 53% | 23% |

United Kingdom data are for England only.

Sources:

- From the book, Health Insurance Systems: An International Comparison, by Thomas Rice, published 2021 by Academic Press, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

Original data from:

Equity

The book also devotes a chapter to equity, using four international datasets and 17 different measures. For each of these variables, wealthier people in a country are compared to less wealthy people to control for other national factors. A few key findings are:

- Americans showed the greatest disparity by income in the likelihood of facing cost-related access problems to medical care

- Americans were second only to Canada in disparity by income in skipping dental care due to costs

- Americans showed by far the greatest disparity by income in the probability of spending 10% or more, and 25% or more, of income on health care. About 14% of Americans with below-average income spent 10% or more of income on health care, compared to 1.4% for above-average income Americans.

Why Do Other Countries Perform Better?

To reiterate, the other countries have universal coverage, low financial barriers to receiving care (Switzerland being somewhat of an exception), more equitable access, comparable or higher service usage rates, and much higher satisfaction with their health care systems. Whereas a few countries do have significant waiting times for some services, this is not the case in others. It should therefore be clear from these cross-national data that the U.S. health care system is far less efficient, and far less equitable, than those of the other nine countries.

Any list of “lessons” is, by its nature, subjective. What appears below are some conclusions about expenditure control and equity based on studying evidence on the health insurance systems within and across the ten countries.

Expenditure Control

The fact that the U.S. spends far more on health care than other countries, even after adjusting for national wealth, has been known for decades. It was nearly 20 years ago that researchers published the finding that the difference is not a result of Americans using more services than others, but rather, that we are paying more per service. There have been some successes; low average generic drug prices[4], coupled with extremely high generic drug usage, are a significant U.S. achievement. But in general, unit prices are far higher than in other countries.

The Health Care Cost Institute examined how much private insurance pays for medical services and prescription drugs in the U.S. as compared to how much is paid by several national health systems in 2017.[5] Table 3 shows ratio of the typical U.S. price to an average of other countries’ prices for five services and six drugs. For the five services – bypass surgery, knee replacement, normal delivery, MRI scan, and colonoscopy – the ratio ranges from 1.9 to 4.3. For example, the price of a bypass operation is three times that of the other countries’ average. The ratios range from 1.3 to 5.0 for the six drugs. Although this does not account for drug rebates to pharmaceutical benefit management companies, on average they reduce U.S. brand name drug prices by only about 18%.[6]

Table 3: Ratio of Average Commercial Insurance Prices in United States Compared to Prices in Other Countries

Ratio Comparison Countries

Procedures

Bypass surgery 3.0 AUS, NETH, SWI, UK

Knee replacement 2.1 AUS, NETH, SWI, UK

Normal delivery 1.9 AUS, NETH, SWI, UK

MRI scan 4.3 NETH, SWI, UK

Colonoscopy 2.7 NETH, SWI, UK

Drugs

Herceptin 3.1 GER, NETH, SWI, UK

Immune globulin injection 2.8 GER, NETH, SWI, UK

Kalydeco 1.3 GER, NETH, SWI, UK

Enbrel 3.3 GER, NETH, SWI, UK

Harvoni 2.2 GER, NETH, SWI, UK

Xarelto 5.0 GER, NETH, SWI, UK

Notes:

- Herceptin is used to treat early-stage breast cancer

Immune globulin injection is used to prevent or reduce the severity of infections - Kalydeco is used to treat cystic fibrosis

- Enbrel is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases

- Harvoni is used to treat hepatitis C

- Xarelto is used to reduce the risk of blood clots

- Source: Health Care Cost Institute. International comparisons of health care prices from the 2017 iFHP survey. https://healthcostinstitute.org/hcci-research/international-comparisons-of-health-care-prices-2017-ifhp-survey

Prices paid by the U.S. Medicare program are, on average, far lower than those paid by private insurers. Kaiser Family Foundation researchers estimate that private insurers pay 89% more for inpatient hospital care, 164% more for outpatient hospital services, and 43% more for physician services.[7] Medicare achieves these lower prices by setting the fees that it pays under the traditional (Parts A and B) part of the program. Such savings are not achievable for prescription drugs, however, because federal law prohibits it. Changing this policy is part of President Biden’s proposed Fiscal Year 2022 federal budget.[8]

Such a policy would comport with how other countries control unit prices. It is useful to consider this from both a conceptual and an implementation standpoint. Conceptually, the countries take advantage of their monopsonistic power. In these countries, all people (with a few exceptions) are part of the public or mandatory plan, so government has tremendous leverage either to set or negotiate for lower prices. Moreover, countries that rely on (non-profit) private insurers typically employ an all-payer system, where every insurer pays the same amount to providers; Germany, France, and Japan provide examples. This consolidates purchasing power. In contrast, U.S. insurers typically do not have monopsony power. Providers have taken advantage of this through both horizontal and vertical integration. One significant trend is hospital systems purchasing physician practices, a result being that more than half of physician practices are now part of, or owned by, health care systems.[9]

More generally, other countries do not shy away from government involvement in health care planning, budgeting, and regulation. Which tools are used vary by country; they include price setting, specifying the number of medical students overall and by specialty, overseeing the premiums charged by private insurers, adhering to global budgets or expenditure caps, and using cost-effectiveness analyses to determine what services are covered and how much they should be paid.

The U.K. has received the most attention for the latter by setting hard limits, e.g., typically not covering new technologies or drugs that cost more than 20,000 to 30,000 British Pounds per quality adjusted life year saved. Other countries use softer but effective tools. Germany, for example, established an independent commission to evaluate each new drug on a six-point scale compared to existing drugs on the market – as well as the prices paid by nearby countries. The drug company can set the price for the first year, but thereafter, the price is based on how much additional benefit patients garner (major, considerable, minor, mixed, none, or less) compared to existing drugs. Negotiation then takes place between a consortium of insurers with the pharmaceutical company.[10]

There are, of course, other things that drive high U.S. expenditures besides high unit prices. Administrative costs are much higher in the U.S. This includes the large number of employees that hospitals and physicians hire to deal with claims – including staff whose job is to maximize reimbursement rates by finding the most lucrative procedure codes, which in turn raises unit prices even more. There is general agreement that “high-tech” medicine is another reason for high U.S. spending, although other countries are catching up in that regard. It is unclear to what extent the physician workforce in the U.S. is “over-specialized” compared to other countries, as there is little international agreement on how to classify different physician specialties. It is also difficult to find reliable cross-national data on physician incomes.

One last cause needs to be mentioned: population health. The U.S. has the highest proportion of people who are obese and who have chronic health conditions – twice the OECD average.[11] Inevitably, this raises spending although there is little agreement on how much. It does not explain why unit prices are higher.

Equity

Whereas universal coverage is the norm elsewhere, about 10% of the U.S. population is uninsured. The uninsured struggle to pay for care; the existence of community health clinics that provide free or nearly free care is crucial, but they are not available to everyone who needs them, and few would claim that they provide the same access as those who are insured. Medicaid now provides coverage for 80 million Americans, but fees (established by states) are often so low that it is difficult to attract hospitals and physicians willing to treat Medicaid patients.

Because other countries have a publicly mandated health insurance system for everyone, their systems are almost by definition more equitable. (Germany provides the only counterexample among the other nine countries, but only 11% of the population is enrolled in a parallel system of private coverage.) One cannot generalize about the generosity of the benefit packages in these countries because it varies a great deal. The same is true of patient cost-sharing requirements. But one thing these countries have in common is a cap on out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses for covered services. For example, the country with the highest OOP spending, Switzerland, establishes a cap of $1,000 euros for adults and 350 euros for children. Compare that to average cap of $4,000 in U.S. employer-sponsored plans and almost $8,000 in the ACA marketplaces. Family maximums are typically about double those. Moreover, most countries do not use deductibles for hospital and physician services, and among those that do, they are far lower than in the U.S. [12]

Equity is nevertheless an issue in other countries even if their concerns are smaller. One example is that the purchase of supplemental insurance policies that provide coverage for more services, pay cost-sharing requirements, and help the owner “jump the queue”. These policies typically are owned by those who are employed and/or have higher incomes. The biggest equity concerns are when a large segment of the population has such coverage, which allows them access to better or quicker care. Australia provides an example of this: about half of the population owns supplemental insurance, which allows them to access private hospitals and choose their surgeon. Waiting times are typically twice as long for those without supplemental coverage. It should be noted queue jumping is not a benefit of supplementary insurance in all countries.

Can We Get From Here To There?

Fundamental healthcare reform is hard and it has its political consequences. When, in 1993, after President Clinton proposed a major reform of the U.S. health care system – an effort that ultimately was unsuccessful – the Democratic Party lost control of both the Senate and the House of Representatives in the next year’s election. The party did not regain either during his remaining six years in office. An almost identical fate befell President Obama. He was able to pass the ACA through the reconciliation procedure in 2010, but during the midterm election eight months later, the Democrats lost the House and did not regain it during his presidency, making it impossible to carry out his legislative agenda for the next six years.

President Biden lived through this history, which is one likely reason that he shied away from endorsing a single-payer system. He has promised to support a “public option,” although at time of writing the details are unclear and it no longer appears to be part of his health policy agenda. There are numerous (and quite varied) ways in which it could be implemented.[13] Any public option proposal would likely offer the potential to lower unit prices, but it would face substantial challenges. If the public option is to generate substantial savings, it needs to pay providers far less than private insurers do. But if it does so, it is not clear how it would be able to garner a sufficiently large provider panel. One solution would be to require participation in public the option (say, if a hospital or doctor wanted to treat Medicare and/or Medicaid patients), but that would undoubtedly encounter the wrath of the provider community, adding to the opposition that would seem inevitable from insurers and the Republican Party.

A smaller reform would involve controlling the prices of brand name drugs, something not only President Biden, but former Presidents Obama and Trump, called for. One method would be to allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices for Part D, its prescription drug benefit program that is sold solely through private insurers. Another complementary method would be to follow the lead of European countries and employ external reference pricing[14], where the Medicare and Medicaid drug payments are based in part on what other countries are paying. Whether such policies will be able to overcome opposition from the pharmaceutical companies is not clear. Moreover, such a policy would not directly affect prices outside of the public insurance programs. Finally, drugs make up less than 15% of total national health care spending, so even if reforms are successfully implemented, they would not make a big dent in overall spending.

President Biden may have a somewhat easier time making the system more equitable, at least at the margin. He has already substantially raised premium subsidies in the ACA marketplaces, albeit securing funding so far for only a two-year period. This will reduce the number of uninsured and lessen the financial burden of those who already have marketplace coverage. At time of writing, his proposed inclusion of dental and vision benefits had been scrapped from the proposed Build Back Better social spending bill due to strong opposition from the dental lobby, which does not want Medicare setting fee levels, and as a way to limit the proposal’s cost. The proposed bill did still contain a new Medicare benefit for hearing aids, and a $2,000 limit on Medicare Part D prescription drug out-of-pocket spending. In addition, the proposal includes the ability of poor people who were excluded from Medicaid coverage in 12 states to obtain that coverage from private insurers through the ACA marketplace, at no cost in premiums, through 2025. Moving beyond health policy, many have touted a provision in the American Rescue Plan, signed into law in March 2021, that provides substantial refundable child tax credits, which is estimated to cut childhood poverty rates in half. Funding was included for only a single year, however. The proposal extends it for one more year, through 2022. All of this is subject to further Congressional negotiation.

The key lesson from my book is that we do not have to start from scratch. Every one of the nine other countries has made effective strides to enhance both the efficiency and equity of their health care systems. With reliable cross-national data increasingly available, the U.S. can benefit greatly by examining both the successes and challenges faced by our neighbors in the quest to create a better performing healthcare system.

References

[1] Rice T. Health insurance system: an international comparison. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2021.

[2] Nolte E, McKee CM. In amenable mortality—deaths avoidable through health care— progress in the US lags that of three European countries. Health Affairs 2012; 31(9):2114–2122.

[3] Commonwealth Fund. Mirror, mirror 2017: international comparisons reflects flaws and opportunities for better U.S. health; 2017 [cited 2021 June 22] Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2017_jul_schneider_mirror_mirror_2017.pdf

[4] Mulcahy AW, Whaley C, Tebeka MG, et al. International prescription drug price comparisons; 2021. Rand Corporation. 2019 [cited 2021 June 22] https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2956.html

[5] Health Care Cost Institute. International comparisons of health care prices from the 2017 iFHP survey; 2019 [cited 2021 June 22] Available from: https://healthcostinstitute.org/hcci-research/international-comparisons-of-health-care-prices-2017-ifhp-survey

[6] Kang B-Y, DiStefano MJ, Socal MP, Anderson GF. Using external reference pricing in Medicare Part D to reduce drug price differentials with other countries. Health Affairs 38(5), 2019:804-811.

[7] Kaiser Family Foundation. How much more than Medicare do private insurers pay? a review of the literature; 2020 [cited 2021 June 22] Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-much-more-than-medicare-do-private-insurers-pay-a-review-of-the-literature/

[8] The White House. Office of Management and Budget. Budget of the U.S. Government: Fiscal Year 2022; 2021. [cited 2021 June 22] Available from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/budget_fy22.pdf

[9] Medscape. More than health of doctors now part of health care systems.; 2020. 2019 [cited 2021 June 22] Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/935249

[10] Rice T. Health insurance system: an international comparison. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2021. Chapter 9: Germany

[11] Commonwealth Fund. U.S. health care from a global perspective, 2019: higher spending, worse Outcomes?; 2020 [cited 2021 June 22] Available from: https://doi.org/10.26099/7avy-fc29

[12] Rice T, Quentin W, Anell A, et al. Revisiting out-of-pocket requirements: trends in spending, financial access barriers, and policy in ten high-income countries. BMC Health Services Research 18(371), 2018.

[13] Kaiser Family Foundation. 10 key questions on public option proposals; 2019 [cited 2021 June 22] Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/10-key-questions-on-public-option-proposals/

[14] Remuzat C, Urbinati D, Mzoughi O, et al. Overview of external reference pricing systems in Europe. Journal of Market Access and Health Policy 3(27675); 2015.