Rola Shaheen, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Radiology at Queen’s University – Kingston, Ontario, and Founder of WILL (Women’s Imaging & Leadership Lab), and Yasser Abu Jamei, Director General, Gaza Community Mental Health Programme

Contact: rshaheen.health@gmail.com

Abstract

What is the message? The paper describes multiple initiatives that arose in response to the Covid-19 pandemic and are addressing mental health challenges in the Gaza Strip.

What is the evidence? The authors draw on their professional experience working in Gaza.

Timeline: Submitted: October 7, 2021; Accepted after review: November 5, 2021

Cite as: Rola Shaheen, Yasser Abu Jamei. Silver Linings; How COVID Changed Health Innovation in Mental Health in Low to Middle Income Countries: Gaza Strip in The Spotlight. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.hmpi.org), Volume 6, Issue 2, 2021.

TO READ THE ARABIC TRANSLATION OF THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE CLICK HERE.

COVID-19 Impact on Mental Health in Low- to Middle-Income Countries

One of the major silver linings of the COVID-19 pandemic is the undeniable recognized importance of mental health care for the global population. Unfortunately, the low- to middle-income countries (LMICs) have classically allocated a relatively small portion of global health resources to mental health.

The emerging and imposed global public health measures to control the pandemic and to minimize related mortality have substantially impacted mental health. The stressors associated with quarantine[1], social distancing, lockdown, the distress of anxiety and fear of infection, COVID fatigue, variability in public health policies, and the pandemic’s economic effect are probably the most impactful factors on mental health. The responses addressing the resulting mental health crisis in LMICs are characterized by different sensitivities and comprehensiveness. Some of them innovative enough to become a model for other countries, while the rest are hampered by the challenges of preexisting fragmented care, tight financial allocations, and the barriers to reaching vulnerable populations.

The global transformation of mental health concepts surfaced during COVID included increased vulnerability to anxiety, normality of “not feeling ok”, and changes in suicide rates. A study by Pirkis et al 2021[2] assessed the suicides occurring in the COVID-19 context in 21 countries, from high-income and upper-middle-income countries, and showed suicide numbers as unchanged or declining in the pandemic’s early months. Unfortunately, there are no comparable data on suicide in low- to-middle income countries during the pandemic. More studies are needed to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on suicide rates in LMICs and populations of diverse ethnic backgrounds.

A recent study by Kola et al[3] highlights innovative responses to mental health services during the pandemic in LMICs, and draws attention to the critical need to shift attention from high-income countries to LMICs. The authors eloquently highlighted the importance of innovative approaches of community-oriented psychosocial considerations while planning for interventions during the pandemic and rightfully going beyond the provision of conventional, narrow biomedical approaches. This is a crucial consideration for non-institutional mental healthcare, as virtual care was expedited during the pandemic[4] and became widely acceptable, and accessible compared to pre-COVID mental healthcare.

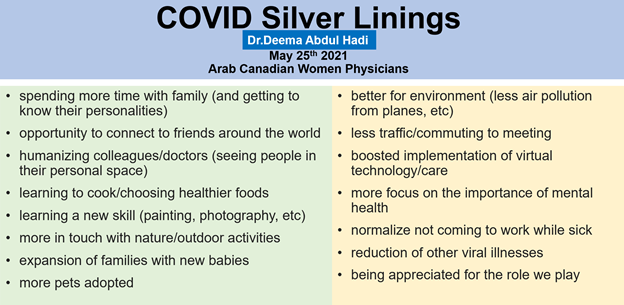

Overall, there has been increased awareness and decreased stigma around mental health issues in the past year[5]. To sum it up, the silver linings of COVID-19 as perceived by a primary care physician, Dr. Abdul Hadi in Ontario, Canada, were highlighted during a lecture addressing Arab Canadian Women Physicians on May 25, 2021 (Figure 1). It is not a surprise that most of the silver linings presented were pertinent to mental health during the pandemic.

Figure 1: COVID Silver linings as perceived by a primary physician practicing in Ontario, Canada.

Source: Dr. Deema Abdul Hadi. Arab Canadian Women Physicians Conference. May 25, 2021.

Mental Health in the Gaza Strip

Gaza Strip Context

Gaza Strip is a historical Palestinian territory on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea with a total area of 365 square kilometers (141 sq miles). Gaza Strip is home for almost two million Palestinians (1,918.000 in July 2020)[6], which makes it one of the most densely populated cities in the world. A narrative overview of mental health in the Gaza Strip unpacks the overall complexity of psychology in this highly condensed population living in the largest open- air prison in the world[7] over the past 14 years.

Despite the ongoing political challenges, the blockade, and the limited access to essential medications and medical equipment, Gazans are known to be one of the most resilient and creative populations, surviving despite successive challenges over the past 4,000 years. The exposure to repetitive, multiple wars in recent history, include the launched assaults [8]on Gaza Strip in 2008-2009, 2012, 2014 and 2021. These conflicts unleashed improvised solutions in the aftermath, emerging from the urgent unmet needs of Gazans’ mental health, with a focus on post-traumatic stress disease (PTSD). However, Dr.Jabr, the Palestinian Head of Mental Health Services, argued at the Build Palestine Summit 2021[9], that in Palestine, PTSD is non-existent; it is not post traumatic, it is chronically traumatic.

Gazans are continually exposed to personal and collective psychological stressors. As explained in a study published by El Khodary et al in March 2021, children in the Gaza Strip are exposed to the uncommon situation of repetitive war-related traumatic events[10], which warrants the critical need for innovative interventional tools, including psychological first-aid programs to unpack and resolve the psychological impact of war-induced PTSD. The trauma is continuous and relentless.

Pre-COVID Mental Health Baseline Innovation Agenda

It is essential to understand the evolving mental health mindset in the Gaza Strip through the unique demographic lens of the two million Gazans. Roughly 70% are refugees (internally displaced Palestinians), of whom 50% are children, with a total median age of 18.[11] In 2018, the average unemployment was one of the highest in world according to the World Bank, reaching up to 50%, with about 80% of population dependent on international assistance[12]. Yet, the Gaza Strip and West Bank have high literacy rates reaching up to 98.7% (females 97.2%, males 98.7%). For youth (ages 15-24), literacy is 98.2%. At the national level, Palestine has an exceptionally high enrollment rate in higher education: 46% in 2007, one of the highest in the world[13].

Reflecting on the demographics, the main constituency for mental health innovation (Figure 2) are by far the young population, including the youth, children, and their parents. Many pre-COVID mental health initiatives focused on improving children’s mental health, including the Gaza Pediatric Mental Health Initiative launched in 2014 by the Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund (PCRF)[14] to address psychologically traumatized children after the 2014 war. In 2018, PCRF moved to an innovative intervention in mental health by training local Community Based Organizations (CBOs) to provide an improved response to crises facing Gaza Strip children. Leveraging access to a global network of experts enhanced this innovative approach by engaging a global ethnopsychologist[15] at PCRF to fill a gap in mental health care in Gaza Strip, providing counsel to solve issues arising from social, cultural, religious, and ethnic factors.

Figure 2: List of key actors and enablers of health innovation. Healthcare Innovation Course April 2021 by Zayna Khayat-Rotman GEMBA-HLS2.

Post-COVID Mental Health Innovation in Gaza

The response to the mental health crisis in the Gaza Strip required innovation at multiple levels, from mobilizing mental healthcare service delivery to community-oriented psychosocial interventions which are rapidly evolving with the unfolding challenges of COVID-19 pandemic in an exhausted and mentally drained war-torn zone. The variable effective psychosocial interventions adopted by the diverse key actors (Figure 3) fit into many key innovative frameworks and concepts included in the Christensen disruption theory.

Figure 3: Elements of disruptive innovation by Christensen

Source: Christensen, Clayton M., 1952-2020. The Innovator’s Prescription: A Disruptive Solution for Health Care. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009

Managing COVID-19 in the Gaza Strip

Although the health resources are very limited in Gaza, stakeholders took strong precautionary measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The Ministry of Health started testing passengers arriving in Gaza, and reinforced home quarantine in the early months of the pandemic. Then in May 2020, arriving passengers were quarantined in school buildings, hotels, hospitals, and health centers. The Ministry recognized an urgent need to address testing at scale and contact tracing, case management capacity, and risk communication and community engagement. The protection of frontline health workers was prioritized by ensuring adequate quantities of personal protective equipment (PPE) and the dissemination of knowledge and skills in infection prevention and control (IPC).

The UNICEF chapter of Palestine published educational material in Arabic for children and parents to raise awareness about the pandemic[17] and promote for preventive hygienic measures, as well as brochures addressing concerns of pregnant women and breastfeeding (Figure 4).

Figure 4: UNICEF educational brochures during the pandemic in Palestine.

Key Actors & Enablers of Mental Health Innovation in the Gaza Strip

Gaza Community Mental Health Program (GCMHP)[18]

GCMHP is a well-established mental health organization. It was founded in 1990, and has received prestigious international awards recognizing exceptional work in the fields of mental health and human rights. The non-for-profit organization offers an integrated and wide spectrum of services directed at improving the mental health of the Palestinian community, including clinical, social, research, and training services. The organization also advocates for the rights of women, children, and victims of violence and human rights violations.

GCMHP provides inclusive, integrated, and comprehensive community mental health services, including psychological assessments, counseling, psychotherapy and occupational therapy, free telephone counseling support, family and community visits, post-treatment follow-up, and supporting self-care through links with community-based organizations, schools, kindergartens, rehabilitation centers, and primary health care clinics.

GCMHP has three community mental health centers (in Gaza city, Deir El-Balah, and Khan Younis) covering all areas of the Gaza Strip. Each community center has a multi-disciplinary mental health team consisting of psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and social worker.

GCMHP offers a diploma in community mental health and human rights and other specialized educational and training programs. Also, it is recognized for building capacities of professionals and actors shaping the Mental Health & Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) network in Gaza Strip (e.g. professionals working in NGOs, primary healthcare, relevant ministries, and UN agencies including UNRWA) through training and supervision sessions.

GCMHP adopts a community-based approach offering clinical therapeutic services and works on institutional capacity building, knowledge dissemination, and public awareness to combat the stigma of mental illness.

GCMHP Experience in the COVID-19 Context

At the beginning of the pandemic, GCMHP prepared an emergency response plan to address risks by utilizing available tools to help inform the development of possible solutions. Measures were applied by GCMHP to respond to different scenarios responding to the epidemiological situation and governmental decisions.

In April 2020, GCMHP suspended all group activities and outreach interventions at kindergartens, schools and in the community. The decision aligned with the state of emergency announced by the Palestinian Authority. Also, GCMHP scaled-down other activities to reduce potential exposure at its facilities and community centers.

GCMHP continued providing core services during full lockdown. Therapeutic services continued to be provided to clients at community centers. This required GCMHP to implement prevention and sanitization measures to reduce exposure, including increasing the duration between follow-up sessions for clients. GCMHP coordinated with the Ministry of Health to conduct home visits and deliver medications to patients at their homes. Other activities were continued remotely, including workshops, training, research, and education activities.

GCMHP scaled up public awareness using media tools and platforms to let the public know about its remote services including psychoeducation, remote counseling, and free telephone counseling services. The telephone counseling service operated by 7 to 10 professionals was scaled up to five channels from one, extending service hours to 12 hours a day and covering weekend days on Fridays and Saturdays. The telephone numbers of all therapists were posted on social media networks.

A culturally sensitive interventional model in Gaza strip was discussed during a Harvard-hosted webinar[19] titled “Gaza Under Siege: From Sheikh Jarrah to Gaza”. The unique model is mindful of cultural and gender sensitivities and involves the deployment of a team consisting of a male and female psychologist to the households of families exposed to psychological trauma. The team systemically screens and surveys the family members to identify patients who need further specialized psychological intervention. This “low-cost innovative business model,” where screeners and therapists meet patients in their comfort zone (patients’ homes), is saving patients’ money on transportation and provides confidentiality to ease concerns around the social stigma of receiving psychological treatment.

In summary, the main lines of intervention by GCMHP[20] include community mental health, psychosocial and rehabilitation, capacity building, awareness raising and community education, scientific research, networking, advocacy, and lobbying and mobilization. The GCMHP is a strategic partner with the Gaza Mental Health Foundation[21], which was established in 2001 to enhance mental health in Gaza.

Gaza Mental Health Foundation

The Gaza Mental Health Foundation partners with other local national, and international stakeholders to drive mental health well-being agenda in the Gaza Strip, particularly for children. In 2015, the initiative/project “We Are Not Numbers” was developed to portray the ongoing personal struggles in Gaza through writing and stories. This innovative approach includes mentoring writers in Gaza to give a much-needed voice for youth and children and tell contextual Gaza stories by Gazans, beyond the numbers highlighted in the pandemic and war news. During COVID, this provided a platform for presenting COVID diaries about the pandemic and the pandemic response. Increasing numbers of youth are highlighting their need for urgent mental health support to help them cope with the repetitive personal and collective traumas in Gaza. Some have started sharing their blogs/ diaries and experiences on social media, for example posting stories and calls for action on the “We Are Not Numbers” website.

The Foundation provides updates on COVID and the health situation in Gaza through strategic collaborations with key partners in the region. The collaboration with Gaza partners in the mental health ecosystem, like the GCMHP, is crucial for avoiding the potential negative outcomes resulting from working in silos. On the ground, the situation is challenging. When a group of psychology students in the Gaza Strip took it upon themselves to offer field work to support families traumatized by wars, without first obtaining training in psychiatry crisis management or aligning efforts with the GCMHP, some of the students involved were diagnosed with PTSD following their volunteer work, warranting treatment at GCMHP.

The NAWA

NAWA[23] is an award winning[24] culture and arts association located in Deir Al Balah[25] in the center of the Gaza Strip. It is a non-profit organization established in 2014 by a group of educated, motivated, and dedicated youths to help empower their local community through culture, arts, non-formal education, and psychosocial support. According to their mission and vision, the services are provided, without discrimination, to thousands of Palestinian children and youth with limited access to cultural, artistic, recreational, and psychosocial support interventions, as well as to parents and educators’ empowerment.

Three years after its establishment, NAWA was awarded the Welfare Association Gaza Award for the year 2017 for its creative intervention in restoring the Saint George (Al Khidr) Monastery, which was built in the 4th century. It is one of the most ancient existing sites where a mosque and a church are located side-by-side. The historical building, which has existed for hundreds of years, was renovated and turned into a beautiful and inspiring children’s library (Figure 5).

In 2020, due to the COVID-19 lockdown, 44% of NAWA’s working days were online. This negatively impacted some activities that require social gatherings, such as children’s visits from local schools. The pandemic required exploring innovative solutions to deliver education and new ways of thinking about the future of education. Online learning is laying the groundwork for innovative distance learning solutions to ensure inclusive opportunities for preschool children who used to play at NAWA Centers prior to the pandemic. The obstacles to e-learning in the Gaza Strip involve infrastructure such as weak internet networks and frequent power outages. Further, this is insufficient awareness among students and their families of the importance of e-learning. Finally, there is low accessibility to computers or smartphones for some students, especially those in the most vulnerable areas within the refugee camps of Gaza Strip.

Working from home during the pandemic was a unique and novel experience for NAWA staff, who used 365 Microsoft Teams applications to manage remote work and build their capacity. To overcome the sudden pause of face-to-face educational activities, NAWA developed an alternative action plan to continue educational support through the provision of educational kits conducted via online tools. WhatsApp and Facebook groups were created and functioned to keep communication with parents in addition to regularly publishing videos of educational, life skills, and psychosocial support.

NAWA also realized that 2020 was a hard year on parents, mainly the mothers: The lockdown and staying at home for a very long time, taking responsibility for their children’s education tasks and follow-up, and the challenges of coping with economic pressures emerging from the lockdown. NAWA provided mothers with debriefing space and awareness sessions with activities and interventions such as self-care, psychosocial support, and child development sessions. Almost all participating mothers indicated a benefit from the psychosocial support, including a feeling of calm and self-control over their anxieties and negative emotions. An example of a successful activity was a “doll making” training course for mothers that resulted in a leveraged positive impact: acquiring new skills, making dolls for their children, reusing consumable materials to make dolls and accordingly, overcoming economic difficulties for the family.

NAWA is collaborating with GCMHP on a “supportive environment to better the future – integrating mental health services in early childhood programs at GAZA Strip–2020”. The program supports Al Hekayat Kindergarten’s psychological interventions. (Figure 6).

Figure 5: The NAWA initiative of establishing Al Khidr Library by restoring the Saint George (Al Khidr) Monastery (built in the 4th century A.D.) جمعية نوى للثقافة والفنون | الصفحة الرئيسية (nawaculture.org)

Figure 6: Al Hekayat Kindergarten established in 2011 by Reem Abu Jaber as a community contribution for Deir Al Balah. She donated it entirely to the NAWA association in 2015. جمعية نوى للثقافة والفنون | الصفحة الرئيسية (nawaculture.org)

Palestinian Children Relief Fund (PCRF)

The Gaza Pediatric Mental Health Initiative led an effort to address the needs of vulnerable children who suffer from chronic diseases such as cancer.[26] In November 2020, they trained teams to reach out to families of children with cancer and blood diseases to offer psychological support through home group sessions. (Figure 7).

Figure 7: The psychologist conducts a home group session for a family from the south of the Gaza Strip whose four children suffer from thalassemia and weak immunity. The mother says: “I spend many days in the hospital because every child needs blood units every three weeks and they are depressed, nervous, anxious, and do not sleep well at night.” These sessions will help improve their psychological lives, which in turn increases the effectiveness of disease resistance. https://www.pcrf.net/news/home-mental-health-sessions-for-sick-children-s-families-in-gaza.html

United Palestinian Appeal (UPA)[27]: Healing Through Feeling program in Gaza Strip

UPA is a nonprofit organization founded by Palestinian-Americans in 1978, with a mission to improve the socioeconomic and cultural development of Palestinian society. Among its multiple program areas are health and wellness. The “Healing Through Feeling” (HTF) program is offered to improve mental health in the Gaza Strip, targeting the health and wellness of Gaza children by increasing awareness of their parents and teachers about trauma and its symptoms. Local mental health practitioners are provided with training and professional development to help them conduct psycho-education sessions for parents and teachers through partnerships with non-governmental kindergartens and summer camps in Gaza. The sessions also provide tools to help children cope with trauma. UPA has a licensing agreement with the American Psychological Association, granting them the rights to translate, format, and print five of their most effective children’s books for Gaza (Figure 8). After each set of psycho-social educational sessions, UPA’s mental health practitioners distribute take-home kits of art supplies, toys, and five American Psychological Association children’s books on trauma to parents and teachers who have completed the training.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, HTF interventions were modified to face the challenges of the spread of the virus in the Gaza Strip with the following adjustments:

- Transitioning HTF to a virtual platform via Facebook Groups, where Mental health Providers (MHPs) can share specialized content and resources on various topics in video and infographic formats on a weekly basis, and engage with parents and caregivers through comments and direct messaging.

- Providing training to MHPs in phone counseling services during crisis conditions, ensuring the effective rendering of services and collection of data, documentation, and facilitation of referrals.

- Modifying all psychoeducational materials and assessment tools such as pre- and post-intervention questionnaires and problem lists to online forms filled out by beneficiaries.

- Networking with kindergartens in the Gaza Strip and creating virtual psychoeducational and counseling groups for caregivers, using platforms like WhatsApp, Zoom, and Google Meet, where parents and caregivers exchange experiences, share knowledge, and acquire more skills to alleviate trauma symptoms in children.

- Providing individual counseling for problems raised by parents and caregivers who sought professional help within the group.

- Adding new optional materials for the beneficiaries and service providers that fit the needs of COVID-19 crises.

Figure 8: United Palestinian Appeal has a licensing agreement with the American Psychological Association granting them the rights to translate, format, and print five of their most effective children’s books https://upaconnect.org/programs/health-and-wellness/healing-through-feeling-program/

Patients

Patients and family caregivers are key players in mental health services innovation. Patients’ empowerment and engagement from the outset in healthcare planning is critical. This is not only because patients have access to information about illness and treatments, but because they also have access to each other – exchanging experiences and rating quality-of-care experiences.

The notion of having access to each other (as per Susannah Fox tweet in 2014[28]), may be new to Western communities, yet it is culturally embedded in many Middle Eastern communities. Patients actively exchange medical experiences without prompting. However, this becomes a major challenge when patients feel entitled to strongly recommend certain medications that worked for them or their neighbors. This is a risky behavior in a jurisdiction that allows for over-the-counter purchase of prescription medications.

It is interesting to label a health behavior as innovative when it is discouraged in certain cultures to avoid adverse medical effects such as drug addiction. Drug addiction, for example to Tramadol, is an important mental health problem in the region.[29]

Startups like “Momy Helper”

As for innovative technology to help parents in Gaza psychologically, a 2019 startup that developed an app “Momy Helper” (Figure 9) was featured in The Independent. The app, founded by Nour Al Khoudary, uses Arabic language to support mothers.It addresses a taboo in the Middle East of “being a mother who cannot cope” and aims to overcome the social stigma around mental health. The app is registered in Delaware and connects Gazan and Arabic speaking women with therapists to provide confidential care.

Domestic violence and psychological abuse of women is on the rise in the Gaza Strip, inevitable psychosocial consequences induced by the high unemployment and poverty rates, as well as the pandemic lockdown. Consequently, depression is on the rise in Gaza Strip.

Figure 9: (Screen shot of Momy Helper website. Users can pay for hour-long consultations with more than 100 specialists). Source: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/gaza-momy-helper-app-arabic-mothers-parenting-psychology-a8887946.html

Barriers & Opportunities: The Role of Culture

Beyond the obvious top three barriers to innovation in mental health in Gaza — political, financial, and workforce — to an important, often overlooked barrier, culture. Mental health is generally undervalued in Palestine. This is not unique to Palestinians. A recent article discussing the Saudi mental health landscape highlights overlapping Saudi and Palestinian cultural barriers despite contrasting financial capabilities and the relatively stable political conditions in Saudi compared to Palestine[31].

The cultural barriers are related to the belief that collective resilience may ease the psychological trauma in the aftermath of war or the pandemic and hamper early intervention to contain and comfort affected population. Without timely and effective intervention, those who are exposed to psychological trauma particularly, in the war-torn zones, will continue to suffer the long-term consequences of PTSD or “ongoing” traumatic stress disorder. It’s a national duty to increase awareness and expand the outreach for patients seeking and receiving psychological interventions to encourage harnessing self-care with tools addressing mental well-being. The societal mindset of considering mental health as a taboo must shift to enable the emergence of very much needed innovative interventional tools in Gaza to facilitate their adoption, implementation, and evaluation at both community and institutional levels.

A compelling opportunity is to build capacity of mental health providers in the Gaza Strip by providing training programs to equip them with the appropriate skillsets and interventions to bridge the gap of the unmet needs.

Looking Forward

There is silver lining in the COVID pandemic is that it expedited innovation in mental health and mobilized care models to cover a wider spectrum of non-institutionalized patients with cost- effective virtual care. During the pandemic, the stigma around mental health has decreased, although substantial work is still needed to break societal and cultural barriers in LMICs including the Gaza Strip. Beyond COVID, serious international and national efforts are needed to end the longstanding political suffering resulting in exceptionally high PTSD[32] and “ongoing” traumatic stress disorder in war-torn Gaza.

TO READ THE ARABIC TRANSLATION OF THIS ARTICLE, PLEASE CLICK HERE.

Acknowledgements

Zayna Khayat, Future Strategist, Teladoc Health, Adjunct Faculty Rotman School of Management- University of Toronto.

Dorgham Abusalim, Communications Manager, United Palestinian Appeal.

Reem Abu Jaber, Executive Director NAWA for Culture and Arts Association.

Steve Sosbee, President/Founder at Palestine Children’s relief Fund.

Nadia Rahwangi, Family and Marriage counselor.

References

[1] https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2820%2930460-8#COVID19

[2] Jane Perkis et al, April 13, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2215-0366(21)00091-2, Lancet Psychiatry 202

[3] https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S2215-0366%2821%2900025-0

[4] https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0399

[5] https://time.com/5835960/coronavirus-mental-illness-stigma/

[6] https://www.indexmundi.com/

[7] https://www.nrc.no/news/2018/april/gaza-the-worlds-largest-open-air-prison/

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Gaza

[9] Summit 2021 – BuildPalestine

[10] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7137754/pdf/fpsyt-11-00004.pdf

[11] https://www.indexmundi.com/gaza_strip/demographics_profile.html

[12] https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/gaza-strip

[13] 2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Education_in_the_State_of_Palestine

[14] https://www.pcrf.net/gaza-pediatric-mental-health-initiative

[15] https://www.pcrf.net/team/dr-alberto-mascena.html

[16] Christensen, Clayton M., 1952-2020. The Innovator’s Prescription : a Disruptive Solution for Health Care. New York :McGraw-Hill, 2009.

[17] مرض فيروس كورونا (كوفيد-19) | UNICEF دولة فلسطين

[19] https://youtu.be/TIZOua3hdlQ

[20] https://gcmhp.ps/publications/1/116

[21] https://www.gazamentalhealth.org/

[22] https://wearenotnumbers.org/home/About

[23] https://nawaculture.org/Home

[24] https://nawaculture.org/Home/Page/5?Lang=en

[25] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deir_al-Balah

[26] https://www.pcrf.net/gaza-pediatric-mental-health-initiative

[27] United Palestinian Appeal (upaconnect.org)

[28] Susannah Fox on Twitter: “The most exciting innovation of our era is not access to medical information, but access to each other.” / Twitter

[29] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3082799/

[30] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/gaza-momy-helper-app-arabic-mothers-parentingpsychology-a8887946.html

[31] https://www.thenationalnews.com/lifestyle/wellbeing/why-saudi-arabia-s-mental-health-landscape-needsmore-attention-we-are-way-behind-in-awareness-1.1232736

[32] https://euromedmonitor.org/en/article/4497/New-Report:-91?fbclid=IwAR3XX7cXf3GcVpZ7MUTBiQ74a4nyfYQc3c8-cp_zliVPvDqDv8HQpEWXzh0