Paul Grootendorst, Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto

Contact: paul.grootendorst@gmail.com

Abstract

What is the message? The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently approved the petition by Florida Governor Ron DeSantis to import drugs from Canada. The plan, however, is unlikely to succeed.

What is the evidence? Canada has no interest in jeopardizing its ability to maintain the low cost of prescription medications and to prevent potential drug shortages. Manufacturers are also unlikely to allow drugs earmarked for Canada to be diverted to the United States if these reimported products displace sales that would have been made at higher U.S. prices.

Timeline: Submitted: February 21, 2024; accepted after review February 22, 2024.

Cite as: Paul Grootendorst. 2023. Florida Wants to Import Low-Cost Prescription Drugs from Canada. Will Its Plan Work? Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.HMPI.org), Volume 9, Issue 1.

Acknowledgements: I thank Kevin Schulman for helpful comments. All errors are mine.

The Florida state government recently obtained approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to import low-cost prescription drugs in bulk from Canada. In this article, I describe Florida’s importation plan, review the reasons that drug prices are lower in Canada and assess the prospects that Florida’s plan will succeed from the Canadian perspective.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis has since 2019 petitioned the U.S. federal government for the right to import drugs from Canada. The U.S. FDA has recently acquiesced. [1] Other state governments are also hoping to import drugs from Canada.[2] Governor DeSantis proposes to initially import drugs from several therapeutic classes for use by beneficiaries of several state-funded drug plans, namely those administered by the Agency for Persons with Disabilities, Department of Children and Families, Department of Corrections, and Department of Health. The program will eventually expand to procure prescription drugs for use by state Medicaid beneficiaries. The state government expects to save $183 million per year once the program is fully implemented.[3].

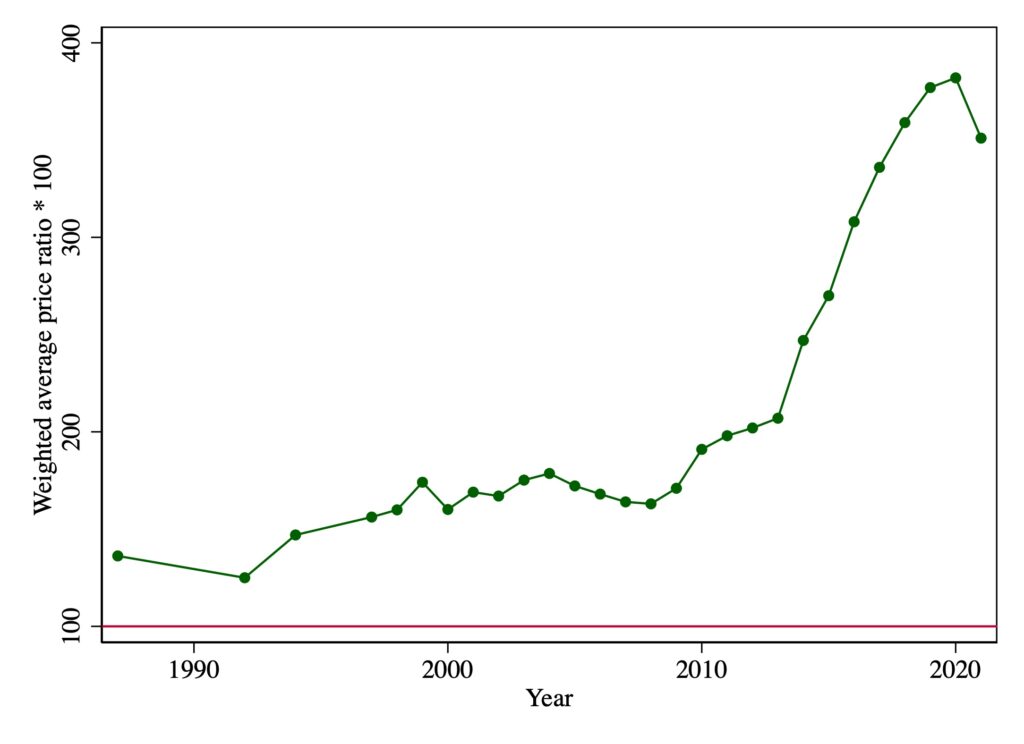

One can understand Florida’s motivation: list prices for patented drugs in the United States are multiples of those paid in Canada. Canada’s Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) has reported on the relative U.S.-Canadian list prices for patented drugs since 1988. The data, illustrated below, indicate that U.S. prices have increased markedly since 2010. In 2021, U.S. list prices were about 3.5 times Canadian prices.

Figure 1. Weighted average US to Canadian patented drug list price ratios, by year, 1988-2021

Note: these are the Canadian sales weighted averages of ratios of U.S. to Canadian pre-rebate prices of patented drugs. Ratios are multiplied by 100. Prices are reported by patentees selling products in both Canadian and U.S. markets. U.S. prices converted into Canadian dollars using market exchange rates. Data source: Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Annual Reports.[4]

The Florida state government obtains discounts off these list prices. By law (OBRA 1990), the rebate on drugs used by Medicaid beneficiaries is 23.1% of the Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) or the difference between the AMP and “best price,” whichever is greater.[5] In exchange for these statutory rebates, Medicaid covers all the manufacturer’s FDA-approved drugs.

The AMP is defined as the average price paid to drug manufacturers by wholesalers for medications sold through retail pharmacies.[1] The “best price” is defined as the lowest available price to any wholesaler, retailer, or provider, excluding the prices negotiated by certain government programs such as the health program for veterans.[5] Under the 340B program, manufacturers are required to provide discounts to “covered entities,” but the sales of these products are not subject to Medicaid rebates nor to inclusion in the best price calculation.[6] State-funded drug plans can also negotiate additional discounts off these statutory price discounts.[5] Even after these discounts, however, state Medicaid programs evidently pay more than Canadian list prices. In 2017, Medicaid paid 45% of U.S. prescription drug list prices; [5] in 2022, Canadian drug plans and hospitals paid about 28% (pre-rebate) of U.S. list prices.[7] This likely explains why the Florida state government wants to import drugs from Canada.

Why are drug list prices lower in Canada? One possible reason is that incomes are lower in Canada. Another reason is Canada’s use of price regulation. Canada’s PMPRB, a federal government agency, uses both internal and external reference pricing to limit the introductory list prices of patented drugs. New drugs that the PMPRB deems to be therapeutically innovative can be priced no higher than the median of the prices charged in various comparator countries. Until recently, the comparison countries were the ”PMPRB7”: France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the U.S. Because many new drugs were launched in just Canada and the U.S., U.S. prices became the effective price ceiling.[8] To lower the price ceiling, in July 2022 the PMPRB changed the comparison countries to the ”PMPRB11”: Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The PMPRB11 removes two high price countries, the U.S. and Switzerland, and adds six countries with relatively low prices: Australia, Belgium, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, and Spain. [9]

Public drug plans in Canada also engage in price negotiation. These federal, provincial, and territorial plans have created two agencies, one of which provides evidence on cost effectiveness of new drugs at their list prices.[10] Using this evidence, the public plans separately identify drugs that meet unmet needs and that could be cost effective at lower prices. They then rely on another agency that negotiates over the size of confidential discounts off manufacturers list prices. [11] The exact discounts are unknown, but they are said to be in the order of 25% of list prices.[12] Governments are willing to walk away if a deal cannot be reached, particularly for drugs which provide small therapeutic value. [13]

Private, typically employer-sponsored, drug plans, which cover about 40% of outpatient prescription drug costs, have historically paid list prices and had minimal formulary restrictions. But during the last decade, they have increasingly also used cost-effectiveness analyses to set maximum reimbursement prices. As with the public plans, the private plans negotiate over the size of the confidential rebate. But because they do not tend to use “take it or leave it” offers, and because each private plan negotiates over a small book of business, the discounts are said to be much smaller than those obtained by the public plans.[12]

Other industrialized countries pay list prices that are even lower than in Canada. For example, list prices paid in Australia, France and the United Kingdom were, respectively, 70%, 73% and 84% of list prices paid in Canada in 2022.[7] One possible reason is that these countries operate national public drug plans, so that they are the single largest purchaser of prescription drugs in the country. Canada’s public drug plans, by contrast, tend to cover those without employer-provided drug coverage, such as seniors, and those with very low incomes. These public plans collectively reimburse only about half of non-hospital prescription drug sales.

In summary, Canadian drug list prices – while high internationally – are much lower than U.S. list prices. This is likely because of income differences, Canada’s federal price regulation and possibly because until recently private plans paid prices close to list price so that charging U.S. prices would price them out of the market. State Medicaid plans obtain statutory price discounts off list prices and can negotiate additional discounts, but evidently net prices remain higher than Canadian list prices. One possible reason for this difference is that state Medicaid programs are mandated to include drugs on their formularies in return for the statutory rebate. In addition, Medicaid is organized at the state level, and each state Medicaid plan accounts for only a small share of the total prescription drug market. Collectively, the Medicaid plans spent $92 billion (before rebates) in 2022; [14] this is only 22% of the $429 billion spent on retail prescription drugs (again, before rebates) in the U.S. in 2022. [15]

What are the prospects for Florida’s drug importation plan? From the Canadian perspective, the proposal appears to be dead in the water. Canada works hard to maintain the low cost of prescription medications to help control the costs of health care in Canada. As a matter of policy, Canada has no interest in jeopardizing its current advantage in prescription drug pricing to support the U.S. market. The Canadian government, and the Canadian pharmaceutical industry, have taken several steps to support its domestic market in the face of programs like the Florida reimportation scheme.

Drug distributors and wholesalers in Canada are federally licensed. [16] Federal regulations in place since 2020 ban the export of pharmaceuticals outside the country if there are “reasonable grounds to believe that doing so could cause or worsen a drug shortage.” [17] So distributors are only able to legally export surplus drugs – i.e. drugs with large inventories, well in excess of domestic demand. It appears that few drugs currently meet this requirement.

Further, almost all Canadian brand drug manufacturers are multinationals that sell in both the U.S. and Canadian markets. These manufacturers charge higher prices in the U.S. because of the structure of the U.S. market. It seems unlikely that manufacturers will allow drugs intended for sale in Canada to be diverted to the U.S. if these reimported products displace sales that would have been made at higher U.S. prices. Thus, manufacturers carefully manage sales to distributors within Canada to ensure that there are not excess inventories available for reimportation to the U.S.

Canadian drug manufacturers have additional ways of preventing diversion by requiring domestic wholesale distributors and pharmacies to refrain from selling drugs to non-domestic customers. Manufacturers added these provisions to their sales contracts with distributors in response to the creation of online pharmacies in the province of Manitoba that were selling drugs to U.S. customers in the early 2000s.[18]

The only conceivable scenario in which multinational manufacturers would agree to reimportation is if the reimported drugs were to be used by Floridians who would be unwilling to pay prevailing U.S. prices. Presumably U.S. manufacturers already have ways of lowering prices to such groups if it is in their commercial interest. This likely explains why the U.S. brand drug manufacturer industry association, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), has also opposed Florida’s drug import plans.[1] [18]

From north of the border, our assessment is that Florida’s plan is unlikely to succeed. If Florida or other U.S. purchasers want lower drug prices, they will have to address the structural issues in the way that drug prices are set in the U.S.

Notes

[1] There is nothing more confusing than how list prices for drugs are reported in the U.S. Wholesale Acquisition Costs (WAC) are meant to be the list prices of drugs before rebates and discounts, while Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) is the price after wholesaler discounts such as cash and volume discounts. Medicare separately considers Average Sales Price (ASP) as the actual price in the market for hospital outpatient reimbursement. The Federal Supply Scale (FSS) price is the government price to purchase drugs for programs such as the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- What to Know About the FDA’s Recent Decision to Allow Florida to Import Prescription Drugs from Canada | KFF. [cited 20 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/what-to-know-about-the-fdas-recent-decision-to-allow-florida-to-import-prescription-drugs-from-canada/#

- Castronuovo C. States Eye Drug Imports From Canada After Florida Approval. In: Bloomberg Law [Internet]. 2024 [cited 24 Feb 2024]. Available: https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/states-eye-drug-imports-from-canada-after-florida-wins-approval

- Florida Becomes First in the Nation to Have Canadian Drug Importation Program Approved by FDA. [cited 20 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.flgov.com/2024/01/05/florida-becomes-first-in-the-nation-to-have-canadian-drug-importation-program-approved-by-fda/

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. Annual Reports – Canada.ca. [cited 20 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/patented-medicine-prices-review/services/annual-reports.html

- Understanding the Medicaid Prescription Drug Rebate Program | KFF. [cited 20 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-medicaid-prescription-drug-rebate-program/

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. The 340B Drug Pricing Program and Medicaid Drug Rebate Program: How They Interact. [cited 22 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.macpac.gov/publication/the-340b-drug-pricing-program-and-medicaid-drug-rebate-program-how-they-interact/

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board. Annual Report 2022 – Canada.ca. [cited 24 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/patented-medicine-prices-review/services/annual-reports/annual-report-2022.html

- Parliamentary Budget Officer. Canadian patented drug prices: Gauging the change in reference countries. [cited 24 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.pbo-dpb.ca/en/publications/RP-2223-008-S–canadian-patented-drug-prices-gauging-change-in-reference-countries–prix-canadiens-medicaments-brevetes-mesurer-importance-modification-dans-pays-reference

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Annual Report 2022 – Canada.ca. [cited 20 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/patented-medicine-prices-review/services/annual-reports/annual-report-2022.html

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. [cited 24 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.cadth.ca/

- pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance. [cited 5 Nov 2023]. Available: https://www.pcpacanada.ca

- Canada. Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. Cost Estimate of a Single-payer Universal Drug Plan. Ottawa; 2023. Available: https://distribution-a617274656661637473.pbo-dpb.ca/c4201c5cc0c9a162ff5f127e98992b64f3547048bf187de65bca2b399f3b9320

- Kyle M, Williams H. Is American Health Care Uniquely Inefficient? Evidence from Prescription Drugs. American Economic Review. 2017;107: 486–90. doi:10.1257/AER.P20171086

- Recent Trends in Medicaid Outpatient Prescription Drug Utilization and Spending | KFF. [cited 20 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/recent-trends-in-medicaid-outpatient-prescription-drug-utilization-and-spending/#

- The Use of Medicines in the U.S. 2023 – IQVIA. [cited 20 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports-and-publications/reports/the-use-of-medicines-in-the-us-2023

- Establishment Licences – Canada.ca. [cited 20 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/compliance-enforcement/establishment-licences.html

- Guide to distributing drugs intended for the Canadian market for consumption or use outside Canada (GUI-0145) – Canada.ca. [cited 20 Feb 2024]. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/drugs-health-products/guide-distributing-canadian-market-consumption-outside-canada.html

- Whitwham B. Dispute over Canada’s online pharmacies heating up. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003;168: 759. Available: /pmc/articles/PMC154941/