Jianhong Wu is a University Distinguished Research Professor, a Canada Research Chair and an NSERC Industrial Research Chair, York University. His research expertise includes infectious disease modeling and data analytics to inform public health decision making and immunization program design and evaluation. He led national teams of disease modelling to support public health emergency rapid response for the SARS outbreak, the H1N1 influenza pandemic, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Swift Mitigations and Tipping Point Cascade Effects: Rethinking COVID-19 Control and Prevention Measures to Prevent and Limit Future Outbreaks (York, Xi’an Jiaotong, Shaanxi Normal, 12/17)

Jianhong Wu, Biao Tang, Yanni Xiao, Sanyi Tang, Aria Ahmad, James Orbinski, York University, Xi’an Jiaotong University, and Shaanxi Normal University

Contact: orbinski@yorku.ca

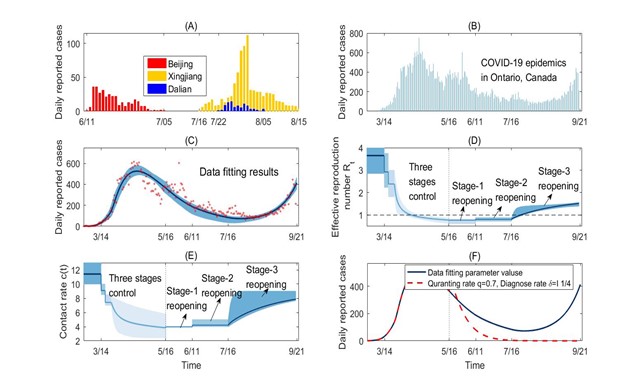

What is the message? Using data from the Canadian province of Ontario (March 12 to September 21, 2020), we model and identify the undesirable cascading effects of premature relaxation of social distancing. When the reproduction rate is near the 1.0 threshold, exponential growth from a large initial pool of SARS-Co-V-2 infections can quickly lead to outbreaks exceeding the contact tracing and testing capacities of public health systems. We then simulate the desirable cascading effects of mitigation interventions that are aimed at quickly reducing the reproduction number well below the 1.0 threshold. This enhancement can bring outbreaks to an end more quickly, and avoiding larger or full scale subsequent waves of transmission. What is the evidence? Using a mathematical model fitted to the Ontario data, we simulated a May 16, 2020 onset in Ontario of an increased quarantine proportion from 40% to 70% and a case detection period shortened from 7.5 to 4 days. With this enhanced testing and contact tracing capacity, the reproduction number would have dropped from 0.78 to 0.3 at the time of Stage 1 reopening. The accelerated rate of case decline across the Province would have ended the first outbreak by the end of June 2020, with a reopening that would have started with a significantly lower number of infections. Timeline: Submitted: December 13, 2020; accepted after revisions: December 16, 2020 Cite as: Jianhong Wu, Biao Tang, Yanni Xiao, Sanyi Tang, Aria Ahmad, James Orbinski. Swift Mitigations and Tipping Point Cascade Effects: Rethinking COVID-19 Control and Prevention Measures to Prevent and Limit Future Outbreaks. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI.org), volume 5, Issue 1, special issue on COVID-19, 2020.Abstract

All Countries are Attempting to Mitigate COVID-19, but with Varying Success

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has led to unprecedented mitigation policies designed to identify, contain, control, and prevent outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Different jurisdictions have taken different approaches, with varying success. This article contrasts experience with mitigating the pandemic in China and in Ontario, Canada. We suggest strategies that can mitigate the pandemic more quickly and effectively.

Experience in China

Mainland China has achieved successful rapid responses to COVID-19 outbreaks, beginning with the complete lockdown of the first reported outbreak epicenter of Wuhan on January 23, 2020. By February 16, 2020, a month-long, nation-wide lockdown was expanded alongside the four-part “All Policy” – Quarantine All, Collect All, Detect All, Treat All.1 Collectively, these public health measures contributed to mainland China reporting no new cases by March 19, 2020. Following subsequent reopening, local outbreaks in Beijing, Xinjiang and Dalian were reported on June 11, July 7, and July 22, 2020 respectively. Swift lockdowns of provinces with affected cities coupled with expanded contact tracing, access to treatment, and rapid population-wide testing in areas with potential exposure to infection contributed to the success of no new cases in over a month, as shown in Figure 1(A).

When three cases of COVID-19 were confirmed on October 11, 2020 in Qingdao, the city was locked down. The governments’ pre-set scenario goal of immediate contact tracing and immediate testing of the entire Qingdao population (9 million) in five days was exceeded, as more than 10 million samples were collected and tested within four days. With 13 positive cases identified, the city was thereafter reopened. These “swift mitigation’” measures – rapidly reducing contacts followed by intensive contact tracing and widespread population testing —characterize the success of treatment, containment, and prevention in mainland China. From the peak to end of the first and -thus far- only wave of COVID-19 in the country, it took about 45 days. While this specific approach may not be feasible in all regions globally, the experience suggests key elements of a critical problem-solving strategy for subsequent waves of population transmission. Successful approaches need to invoke swift, focused and coherent mitigation interventions that are likely to be more effective than those that are piece-meal, poorly coordinated, and/or ill-timed.

Experience in Ontario, Canada

Modeling social distancing interventions: Initial reductions with risk of recurrence

A similar set of mitigation strategies was employed by governments around the world in their initial response to the first wave of SARS-CoV-2.2,3,4. Taking the Canadian province of Ontario as an example, we modelled a series of escalating social distancing mitigation interventions that were implemented in three consecutive stages between March 14 and May 16, 2020, followed by staggered de-escalation through to September 21, 2020 (Figure 1B). In addition to school closures (Stage 1) and restrictions to public events and recreational venues (Stage 2), the “swift mitigation” measures of shutting down all non-essential workplaces (Stage 3) was essential to reducing the Effective Reproduction Number, below the 1.0 threshold by on or around April 16, 2020.

This trend marked a strong start but was still susceptible to the emergency of new infections. Reflecting the sum effect of all mitigation interventions, when approaches the 1.0 threshold and the number of infections in the population is significant, a subsequent wave of infection is likely to emerge. A new wave is particularly likely where increased social contact allows for broader-based transmission, thereby driving above the 1.0 threshold.

Recurrence: April to September 2020

Using a transmission dynamics model fitted to the daily incidence data in Ontario (Figure 1C), we observed two key trends. First, although decreased to below 1.0 around April 16, 2020, it remained close to this threshold, resulting in only a slow case decline rate. Second, even with the quarantine proportion and case detection rate achieved at the end of Stage 3, can exceed the 1.0 threshold when the contact rate reaches only two-thirds of the normal full rate after reopening. This indeed happened when the province moved to regional de-escalation from Stage 3 on July 16, 2020 allowing businesses and public places in approved regions to re-open with safety and occupational measures in place.

Our estimation shows a gradual increase in the contact rate (Fig. 1E). However, contact tracing coverage and testing capacity remained relatively unchanged, with the quarantine proportion at 38% and a diagnostic testing confirmation period of 7.5 days after infection. As a result, the effective reproduction number gradually increased to 1.5, leading to a second wave in September 2020. In turn, the Province re-imposed modified Stage-2 mitigation measures in some hotspots.

Simulations: What if contact tracing had been higher and testing faster?

Using our model, we simulated a May 16, 2020 onset in Ontario of an increased quarantine proportion from 40% to 70% and a case detection period shortened from 7.5 to 4 days (Figure 1F). With this enhanced testing and contact tracing capacity, would have dropped from 0.78 to 0.30 at the time of Stage 1 reopening. The accelerated rate of case decline across the Province would have ended the first outbreak by the end of June 2020, with a reopening that would have started with a significantly lower number of undetected infections (if any). This would have allowed public health resources to be mobilized for swift and focused responses to any new localized hotspots, and likely avoiding a full-scale second wave of transmission.

In contrast to these desirable cascade effects – where enhanced social distancing measures maintain a low leading to reduced number of new infections, together with swift public health testing and contact tracing – Ontario experienced the undesirable cascade effects of pre-mature relaxation of social distancing. Unfortunately, as a result, the exponential growth from a large initial pool of undetected infections quickly led to outbreaks exceeding testing and tracing capacity. This negative cascade reinforced the resurgence of the pandemic in Ontario.

The power of tipping points: Triggers for a second wave in Ontario?

Stage 1 reopening in Ontario started on May 16, 2020 even as new cases continued to be reported daily, suggesting that may have been hovering around the 1.0 threshold. According to catastrophe theory and dynamic systems bifurcation theory, the province was at a “bifurcation point” with subsequent tipping point cascade effects, when de-escalation of social distancing began on May 16, 2020.

Tipping point cascade effects suggest that while a small increase to the bifurcation parameter (in this case, can trigger a second wave, further reduction of this bifurcation parameter near the tipping point can accelerate an exponential decline in new case transmissions. In Ontario, the number of total and new daily cases was judged to be “small” — wrongly, it appears — in deciding to begin reopening on May 16, 2020. Public health resources were likewise judged to be sufficient, instead of scaling testing, contact tracing, quarantine, and isolation efforts, which would lead to a further decrease of . Hence, the analysis suggests a missed opportunity to prevent the second wave.

Implications for Global Mitigation During the Second Wave

Similar situations globally can be identified on the WHO Coronavirus Disease Dashboard, with countries reporting subsequent waves of transmission with even larger peaks that have imposed significant challenges to public health systems in the face of public fatigue.5 Prolonged lockdowns have become a real possibility in many parts of the world. Yet this time, a critical problem-solving strategy for subsequent waves of COVID-19 population transmission should invoke swift, focused, and coherent mitigation interventions that aim to reduce the effective reproduction number well below the 1.0 threshold. This approach is likely to be more effective than strategies that are piece-meal, poorly coordinated, and ill-timed.

At least two factors have contributed to the occurrence of second waves in many countries. First, SARS-CoV-2 has high transmissibility with a high basic reproduction rate when activities resume.6,7 Second, although most countries implemented a range of public health mitigation interventions, implementation has often been lax and inconsistent, resulting in tipping point cascade effects that lead to further outbreaks.

One important strategy for controlling infectious disease outbreaks is to reduce below the 1.0 threshold. However, it is easy to stop too soon. Given the high transmissibility and reproduction rate of SARS-CoV-2, an effective reproduction number below but near this threshold could result in a prolonged period until the end of the outbreak.

Looking Forward

The global scale of the COVID-19 pandemic has catalyzed to significant advancements in public health interventions, including rapid testing and enhanced contact tracing capacities. With these, the period from peak to end of the second wave can and should be shortened when tipping point cascade effects are fully taken into account.

Effective strategies to confront subsequent waves of outbreaks and to safely reopen from full, staged or localized lockdowns require swift, focused, and coherent mitigation interventions to quickly reduce the effective reproduction number well below the 1.0 threshold. Enhancing public health mitigation efforts at the bifurcation tipping points can further accelerate the decline of new cases, followed by enhanced rapid testing and contact tracing when the case numbers are small.

Figure 1.

- Panel (A) Local outbreaks in Beijing, Xinjiang, and Dalian: shock mitigation and rapid testing enabled quick control8.

- Panel (B)-(F) COVID-19 epidemic in Ontario, Canada from Feb 26 to Sep 21, 2020. Here, the model by Biao et al.9 is used to evaluate the contact rates, diagnosis rate, and quarantine proportions, following the timelines of three stages of social distancing escalation to control the 1st wave, and the three stages of reopening. Social distancing de-escalation led Ontario to reopen on May 11. In our simulation (Fig 1F), with the quarantine proportion increased from 38% to 70% and diagnosis period shortened from 7.5 to 4 days starting on May 16, the reproduction number would have decreased with an accelerated rate of decline, such that the first outbreak would have ended by the end of June and the reopening would have started with very small number of infections. Public health resources could then have been mobilized for swift reaction to any new local hotspot to avoid a full scale second wave. In contrast to this desirable cascading effect — contact reduction leads to a small number of new infections and enables swift public health tracing and testing — Ontario experienced the undesirable cascading effects of relaxation of social distancing too early, such that the exponential growth from a large initial pool of infections quickly led to outbreaks exceeding the tracing and testing capacity.

Author detail: Jianhong Wu1,3,†, Biao Tang2,4,†, Yanni Xiao2,4, Sanyi Tang5, Aria Ahmad,6 James Orbinski6

1 Laboratory for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, York University, Toronto, Canada

2 Interdisciplinary Research Center for Mathematics and Life Sciences, Xi’an Jiaotong University, China

3 Fields-CQAM Laboratory of Mathematics for Public Health, York University, Toronto, Canada

4 School of Mathematics and Statistics, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China

5 School of Mathematics and Information Science, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China

6 Dahdaleh Institute for Global Health Research, York University, Toronto, Canada

† The two authors contributed equally

Author contributions: Conceptualization, J.W., B.T. and J.O.; validation and simulation, B.T.; data curation, B.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.T., Y.X., and S.T.; writing—review and editing, J.W., B.T., and J.O.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) rapid research program, the Canada Research Chair Program and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (JW), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 11631012 (YX, ST), 61772017, 12031010 (ST)).

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Xiao et al., Linking key intervention timing to rapid decline of the COVID-19 effective reproductive number to quantify lessons from mainland China, Int. J. Infect. Dis. 97, 296-298 (2020).

- S, Hsiang et al., The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic, Nature, 584, 262–267 (2020).

- Tian et al., An investigation of transmission control measures during the first 50 days of the COVID-19 epidemic in China, Science, 368, 638-642 (2020).

- J. Kucharski et al., Effectiveness of isolation, testing, contact tracing, and physical distancing on reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in different settings: a mathematical modelling study, Lancet Infect. Dis. 20(10), 1151-1160 (2020).

- WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, https://covid19.who.int/table. [Accessed at Oct 15, 2020].

- Sanche et al., High Contagiousness and Rapid Spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 26(7), 1470-1477 (2020).

- Flaxman et al., Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries.

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/gzbd_index.shtml [Accessed on Oct. 26].

- Tang et al., De-escalation by reversing the escalation with a stronger synergistic package of contact tracing, quarantine, isolation and personal protection: Feasibility of preventing a covid-19 rebound in Ontario, Canada, as a case study. Biology 9(5), 100 (2020).

Health and Economic Trade-Offs of COVID Policies in Sub-Saharan Africa (Univ. of Michigan, Makerere Univ., 12/17)

Paul Clyde, University of Michigan, and Fred Matovu, Chrispus Mayora, and Peter Waiswa, Makerere University

Contact: pclyde@umich.edu

What is the Message? This article describes key changes in operations, communication, and security that are central to moving ahead effectively as we deal with COVID-19, including designation of specialty care facilities, creating emergency management plans, changing appointment policies, coordinating social distancing, managing hygiene protocols, and expanding testing. What is the Evidence? The authors draw upon their recent experience at relevant medical centers. Timeline: Submitted August 5, 2020; accepted after revisions: August 31, 2020 Cite as: Paul Clyde, Fred Matovu, Chrispus Mayora, Peter Waiswa. 2020. Children Are at Low Risk for COVID But at High Risk for the Policies Designed to Curb COVID. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI.org), Volume 5, Issue 1, special issue on COVID-19, December 2020Abstract

“Part of the challenge here is that we’ve lost the nuance. Some people are saying this is a hoax, it’s fake, it’s not serious. Other people may be saying it’s the worst thing in the world, a zombie apocalypse. It’s neither. This is a terrible pandemic. It has killed 130,000 Americans. It has sickened many, many more. And we don’t yet know what the long-term complications of some of the illness [are]. But it is true that 99% of people who get it will survive.”

— Former CDC Director Dr. Thomas Frieden. [i]

Attempts to curb the pandemic can affect other health and economic targets

Government actions taken in response to the pandemic are often credited or blamed for their effect on the disease itself; less so for the other, more indirect, costs of these actions such as reduced attention to other illnesses. Part of that may be the lack of concrete numbers. Decision makers naturally gravitate toward hard numbers, and hard numbers are most readily available for those who contract COVID and those who die with it. Mortality and morbidity that result from actions taken to try to prevent the spread of the disease are more difficult to measure, much less attribute to specific government policies.

Nonetheless, a number of organizations have started documenting these costs and developing estimates of their magnitude and severity. For example, with respect to non-COVID health consequences, clinicians are expecting an increase in cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis and treatment in western markets[ii] or due to constraints occasioned by suspension of public transport in Africa.[iii] For similar reasons, heart disease,[iv] mental health and other chronic diseases can also be expected to increase.[v]

The economic consequences of government actions taken to curb the effects of COVID have been even less clear. Some point to the significant economic consequences even in Sweden, where the government has employed a relatively light touch, as evidence that the economic downturn is a result of consumer fear rather than government action. Others assert that, even if there are negative economic consequences from government actions, these surely pale in comparison to saving lives, implying that economic downturns don’t cost lives

Data that speak to the economic consequences of fear are relatively scarce just because we only have a few months to observe. Existing studies show that the lockdown itself, and not just fear, is having an effect though some suggest the lockdown accounts for a small portion of the economic downturn,[vi] while others suggest lockdowns account for most of the decline.[vii]

Looking at Sweden’s economy highlights another difficulty in isolating the effect of the lockdowns themselves. Preliminary estimates of Sweden’s GDP in the second quarter suggest that Sweden did not fare well even relative to its neighbors, as it saw GDP drop 8.6% in the second quarter of 2020. Sweden did, however, fare better than most European countries and than G7 countries except Japan,[viii] the only G7 country that also adopted a relatively light touch.[ix]

The problem with these comparisons is that, like the disease itself, the economic consequences of COVID responses are not confined to political boundaries. Producers rely on export markets and consumers and producers rely on imports. Thus, the citizens of Sweden and any other country will suffer the consequences of actions taken by governments all over the world, especially close trading partners.

The link between the economy and mortality rates is clearer, although the health consequences of an economic downturn manifest themselves in other ways as well. Just as COVID may have long term health effects short of death that are not well understood yet, an economic downturn affects other aspects of health and quality of life. Nonetheless, since mortality garners substantial attention with respect to COVID, we use research on the relationship between economic downturns and mortality to estimate the potential effect of the economic downturn associated with COVID on mortality alone. In an effort to be concrete and tractable, we focus on the mortality rate of a specific group: children under the age of five in Uganda.

Health and economic impact in sub-Saharan Africa

Since the COVID-19 virus started in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019, it has been both a surprise and a relief to see that the virus itself has killed relatively few people in sub-Sahara Africa. The economic effect has, however, been devastating.

In Uganda, the Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development released April 2020 trade statistics which revealed that exports had fallen by 34.3%. Imports declined by 38.5% over the same period. This decline is attributed partly to airport closures and travel restrictions more generally. As but one indication of the severe consequences implied by these figures, fully 42% of tax revenue for Uganda is collected through international trade.[x]

When households have enough income, they are able to make reasonable choices of nutritious foods and other essential goods and services for their household members but, when people do not have enough income, health suffers and mortality rates go up. Recent data from Uganda shows that outpatient visits, antenatal visits, live births in healthcare facilities, immunizations have all dropped and in many cases, dropped by more than 10% relative to the same period the year before. The number of children with low birth weight increased relative to the preceding year[xi]. Hence, the reduction in income has led to increased health risks. [xii]

We can quantify the effect of the COVID economic downturn on mortality by using previous estimates of the effect of sudden declines in GDP on mortality. The GDP growth rate in sub-Saharan Africa is expected to decrease by as much as 8%. A World Bank study predicted that GDP would decrease from 2.4% in 2019 to as low as -5.1% in 2020.[xiii] The IMF is expecting a decrease in GDP of 5.4% in 2020.[xiv] Given the pre-COVID expectations of a GDP increase, this implies a decrease of about 8%.

Using estimates from a study of the effect of the 2008 financial crisis on infant mortality, an 8% decrease in GDP per capita could result in almost 150,000 more infant deaths.[xv] Estimates from other studies on infants[xvi] and children under 5 are roughly consistent with this, suggesting an 8% decline in GDP could lead to hundreds of thousands more deaths of children under 5.[xvii]

Note that the decline in GDP estimated by the World Bank and IMF was for the overall economy. This will understate the effect on GDP per capita if population is growing, as it is, in sub-Sahara Africa. Thus, the impact of COVID on the economies in many countries in the region is such that hundreds of thousands of children could die. Indeed, that seems likely.

We need to pay attention to trade-offs

Decision makers in governments around the world are faced with difficult decisions. Already, more than one million people have contracted COVID and died. The true number may be higher if some have died with COVID even though the disease was not diagnosed or, instead, may be lower if some people had COVID but died due to some other disease.

The uncertainty surrounding that estimate is much less than the uncertainty about the number we have tried to estimate: the increase in deaths due to the economic consequences of COVID and actions taken to prevent it. It would be preferable to wait until the data on both COVID mortality and the economic effects were more reliable, but since decisions are being made in real time, we will have to make do with what we have in real time. It would be a serious mistake to dismiss either the costs or the benefits just because of the uncertainty.

Consider three points regarding the numbers we presented above.

First, we have looked only at the economic effect on the number of deaths of children under five in sub-Sahara Africa. We do not consider the effect of delayed diagnosis and treatment of other diseases either in Africa or other countries. We do not discuss the effect on the over-five year child population in sub-Sahara Africa and we do not discuss the effect of poverty in other countries. All of these populations will also be affected.

Second, government actions to stop COVID will not bring COVID related deaths to zero and are not solely responsible for the decrease in economic activity resulting from the pandemic. Even in the absence of government actions, there would be negative economic consequences from COVID. Many are fearful and would choose to stay home and engage in the economy less, even if governments allowed it. We discussed this earlier but have made no attempt to isolate the effect of government actions and separate them from the “natural” effects on the economy.

However, we have evidence that at least some of the economic consequences are a result of government policy – and some studies suggest policy is the cause of most of the economic downturn. Similarly, even when governments take relatively drastic actions they do not necessarily reduce mortality dramatically or permanently. The state of Michigan in the U.S., for instance, has a population that is very similar to Sweden’s, and its governor issued a shelter in place order for 2 months, closing many businesses, limiting the services offered by hospitals, and other limitations. Yet, despite the stricter measures, the number of deaths related to COVID are about 45% more in Michigan than in Sweden.

Third, the estimates for an increase in mortality rates in sub-Sahara Africa are extremely conservative because they are one-year estimates and many of the newly-impoverished individuals are likely to remain in poverty for many years to come. Thus, the number of deaths due to the economic downturn will be much higher than the estimates presented above. To give some idea of the long-term effect, we can return to the 2008 financial crisis. The World Bank estimated that 70 million people who would not otherwise have been in poverty would remain in poverty into 2020 as a result of the 2008 financial crisis.[xviii]

Looking forward

Globally, about 60 million people die in the world every year. At the current pace, more than 1.5 million will contract COVID and die. Oxfam posted a briefing stating that as many as 12,000 hunger deaths per day could be related to COVID.[xix] Remarkably, their “Actions Needed” did not mention anything about the deleterious effect on mortality of government actions designed to limit the effect of COVID.

But we know anecdotally that the actions governments take to limit COVID deaths have caused people to die.[xx] We know that hundreds of thousands of children under the age of 5 are likely to die as a result of the economic consequences of COVID. While fear may be driving some of the economic downturn, government policy is also affecting it and to the extent that it is, governments need to keep these consequences in mind the same way they consider the effect of the disease itself.

During this horrible pandemic our actions, whatever they are, have costs and consequences. It is therefore important that when developing government policies, we identify and evaluate these as best we can. Let us be done with saying that the tradeoff is between lives saved and the economy as if helping the economy does not also save lives.

Governments have an array of options available to them, and each contains its own set of costs and benefits. Requiring masks to be worn in public appears to pose few costs, while providing significant benefits by slowing the spread of the virus. By contrast, forcing businesses to stop offering services does pose a cost, and has economic consequences that extend beyond the borders of the governing authority. Stopping elective surgeries in areas that are not experiencing significant outbreaks is different from stopping elective surgeries in areas that are facing a shortage of hospital beds due to COVID. The decisions governments face right now are difficult, but let’s be clear: it is not a question of saving lives or not saving lives. Rather, it is a question of trying to protect the lives of people from one malady (COVID) as opposed to another (the consequences of serious economic decline and increased poverty). As Dr Frieden suggests in the quote at the beginning of this article, it requires a more nuanced approach.

References

[i] David Morgan CBS News July 6, 2020, and 12:33 Pm, “U.S. Is an ‘Outlier’ in Global Coronavirus Fight, Former CDC Director Says,” accessed September 21, 2020, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/coronavirus-united-states-former-cdc-director-tom-frieden/.

[ii] Norman E. Sharpless, “COVID-19 and Cancer,” Science 368, no. 6497 (June 19, 2020): 1290–1290, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abd3377.

[iii] Geoffrey Mutegeki, “Covid 19: Delayed Treatment Puts Cancer Patients At Risk,” accessed September 21, 2020, https://www.newvision.co.ug/news/1517647/covid-19-delayed-treatment-cancer-patients-risk.

[iv] “Fear of COVID-19 Keeping More than Half of Heart Attack Patients Away from Hospitals,” accessed September 21, 2020, https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/Fear-of-COVID-19-keeping-more-than-half-of-heart-attack-patients-away-from-hospitals, https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/Fear-of-COVID-19-keeping-more-than-half-of-heart-attack-patients-away-from-hospitals.

[v] Steven H. Woolf et al., “Excess Deaths From COVID-19 and Other Causes, March-April 2020,” JAMA 324, no. 5 (August 4, 2020): 510–13, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.11787.

[vi] Austan Goolsbee and Chad Syverson, “Fear, Lockdown, and Diversion: Comparing Drivers of Pandemic Economic Decline 2020,” Working Paper, Working Paper Series (National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2020), https://doi.org/10.3386/w27432.

[vii] Olivier Coibion, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Michael Weber, “The Cost of the Covid-19 Crisis: Lockdowns, Macroeconomic Expectations, and Consumer Spending,” Working Paper, Working Paper Series (National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2020), https://doi.org/10.3386/w27141.

[viii] OECD, “GDP and Spending – Quarterly GDP – OECD Data,” OECD, accessed September 21, 2020, http://data.oecd.org/gdp/quarterly-gdp.htm.

[ix] Eric Feldman, “Did Japan’s Lenient Lockdown Conquer the Coronavirus? | The Regulatory Review,” June 10, 2020, https://www.theregreview.org/2020/06/10/feldman-japan-lenient-lockdown-conquer-coronavirus/.

[x] Ali Twaha, “Covid 19: Uganda’s Exports Decline By 34.3%,” accessed September 21, 2020, https://www.newvision.co.ug/news/1521359/covid-19-uganda-exports-decline-34.

[xi] Ministry of Health, Uganda, “Impact of COVID-19 Containment Measures on Reproductive Maternal Newborn Child Health and Adolescent Health and HIV Service Delivery and Utilization in Busoga Sub Region, Uganda,” August 2020.

[xii] Jed Friedman and Norbert Schady, “How Many Infants Likely Died in Africa as a Result of the 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis?,” Health Economics 22, no. 5 (2013): 611–22, https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2818.

[xiii] The World Bank, “Overview,” Text/HTML, World Bank, accessed September 21, 2020, https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/overview.

[xiv] IMF, “Six Charts That Show Sub-Saharan Africa’s Sharpest Economic Contraction Since the 1970s,” IMF, accessed September 21, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/06/27/na062720-six-charts-show-how-the-economic-outlook-has-deteriorated-in-sub-saharan-africa-since-april.

[xv] Friedman and Schady, “How Many Infants Likely Died in Africa as a Result of the 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis?”

[xvi] Sarah Baird, Jed Friedman, and Norbert Schady, “Aggregate Income Shocks and Infant Mortality in the Developing World,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 93, no. 3 (August 5, 2010): 847–56, https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00084; Friedman and Schady, “How Many Infants Likely Died in Africa as a Result of the 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis?”

[xvii] Stephan Klasen, “Poverty, Undernutrition, and Child Mortality: Some Inter-Regional Puzzles and Their Implications for Research and Policy,” The Journal of Economic Inequality 6, no. 1 (March 1, 2008): 89–115, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-007-9056-x.

[xviii] The World Bank, The World Bank Group’s Response to the Global Economic Crisis, Independent Evaluation Group Studies (The World Bank, 2011), https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8665-1.

[xix] Oxfam, “The Hunger Virus: How COVID-19 Is Fueling Hunger In A Hungry World,” accessed September 21, 2020, /explore/research-publications/hunger-virus-how-covid-19-fueling-hunger-hungry-world/.

[xx] Evelyn Lirri, “How Uganda’s Tough Approach to Covid-19 Is Hurting Its Citizens,” accessed September 21, 2020, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/science-and-disease/ugandas-tough-approach-covid-19-hurting-citizens/.

The Role of Shared Services in Supporting Ontario’s Move to Bundled Care and Value-Based Procurement

Lauren M. Bell and Jiayan (Maggie) Chen, Innovation & Strategic Partnerships, Plexxus

Contact: maggie.chen@plexxus.ca

Abstract

What is the message? From the perspective of a shared services organization, the paper discusses some of the challenges in linking procurement to outcomes as a core component of bundled payments relative to the stage of maturity in implementing bundled care in Ontario, the largest province in Canada. Despite the challenges, value-based procurement for specific portions of the bundles is beginning to make a difference in the quality and cost of services in the province. Examples include procuring across the patient continuum to enable bundling implementation for hip and knee patients.

What is the evidence? The authors work with Plexxus, a leading Shared Services Organization in Ontario, which has pioneered value-based procurement for multiple hospitals in the province.

Timeline: Submitted September 11, 2020; accepted after review: September 17, 2020.

Cite as: Lauren Bell and Jiayan (Maggie) Chen. 2021. The Role of Shared Services in Supporting Ontario’s Move to Bundled Care – Understanding the Complexity of Aligning Procurement and Bundled Payments through Value-Based Procurement. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI.org), Volume 6, Issue 1, Winter 2021.

Bundled Care in Ontario – Background & Current State

Health systems worldwide have been adopting value-based healthcare models to deliver better patient outcomes at the same or lower costs. Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, has also been progressing towards a more value-based healthcare system through the gradual implementation of more integrated care delivery and funding models, commonly known as bundled care. Although bundled care is no longer an entirely new concept in the province, implementation has been incremental and spanning only several patient conditions.

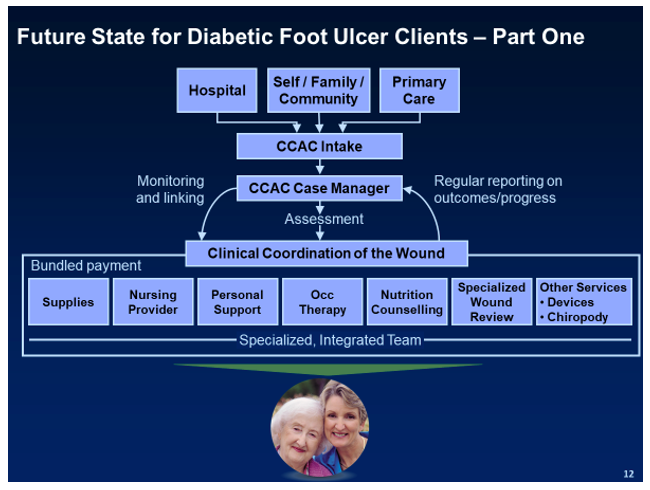

Generally speaking, a fixed payment is allocated for a defined episode of care to a bundle holder who, in turn, works to arrange care for the patient across multiple care settings. This funding model aligns financial incentives with outcomes, promotes care coordination and integration, and improves patient satisfaction. The model also helps to reduce the cost of care by supporting and shifting care to less resource-intensive settings. In the literature, providing care through bundled payments has demonstrated promising results for improving the value of healthcare spending in Ontario and other jurisdictions, such as the U.S. and Netherlands. [1], [2]

Building on the foundation of Quality-Based Procedures (QBPs)[1] and the success of early pilot programs in Ontario, the Ministry of Health (MOH) began implementing bundled care programs at scale during the past couple of years. Since April 2019, a unilateral hip and knee bundle has been implemented across Ontario hospitals that perform joint replacement surgeries. For other bundles such as those that cover shoulder replacement surgeries, Ontario is taking a voluntary and phased approach to implementation due to the complexity of elements such as data collection, reporting, and wanting to assess lessons learned appropriately. [3]

Value-Based Procurement can Support Ontario’s Move to Bundled Care in Helping Purchasers Extract Greater Value from Suppliers and Align around Outcomes

The role of Plexxus

Recent analysis shows that Ontario spends close to 25% of its annual healthcare budget to procure products and services for healthcare providers to deliver patient care. [4] As one of the leading shared services organizations (SSOs) in the province, Plexxus, based in the Greater Toronto Area, focuses on delivering value through service excellence, collaboration, and scalable systems and processes to its 20 member and customer hospitals. Since its inception in 2006, Plexxus has achieved $350 million in savings through its fully integrated supply chain model, inclusive of a scalable digital platform (i.e., SAP) to enable efficient service delivery, advanced decision-making, and analytics.

In addition, Plexxus has significant expertise in complex procurements, with experience across a broad range of categories and competencies, including implementing the first provincial value-based procurement (VBP)[2]of implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) and cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRTs) devices. Through applying the principles and practices of VBP, Plexxus has and continues to play a crucial role in successfully leading initiatives that create tangible improvements for hospitals and patients.

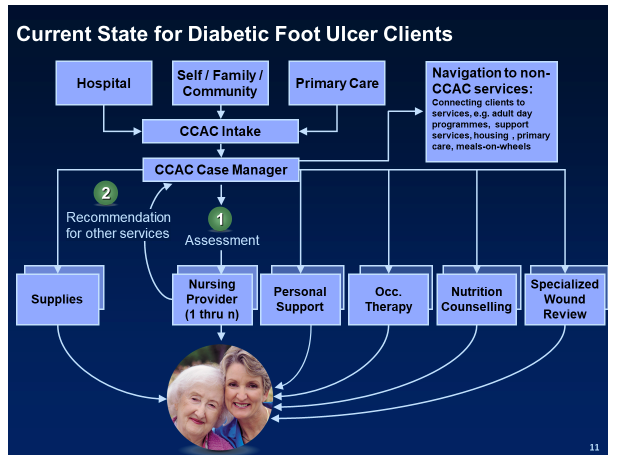

The opportunity for bundled care

Bundled care focuses on optimizing care provided across an entire patient pathway rather than individual components of the patient journey in isolation. The episode of care is defined by a best-practice care pathway spanning multiple care settings from hospitals to home and community service providers. By its nature, each pathway relies on both goods and services that SSOs such as Plexxus procure to support the effective delivery of patient care. However, the province’s current procurement model was established with a more sector-based view, where each sector has a very different approach to managing supply chain and procurement of goods and services. This presents a unique opportunity for the province to consider progressive approaches to procurement, such as opportunities to procure for a larger part of the patient pathway to further drive value for patients and purchasers.

Procurements for bundled episodes are a type of VBP that requires a myriad of products and services spanning multiple care settings. By factoring both quality and total cost of patient care into the procurement equation, the new VBP approach focuses on procuring products and services that bring the most value. Value can come in the form of procuring standardized products and services across the continuum of care, which helps narrow unnecessary variation in patient outcomes and drive additional efficiencies through product alignment. [4] For example, when patients move from one healthcare provider to another across a patient pathway, they should be treated with standardized supplies regardless of the care setting unless there is a substantial clinical reason to switch to a different product.

Value might also come from improving the quality of care and patient experience through collaborative purchasing decisions. When an acute care hospital procures medical devices for surgical patients, the hospital should work with their bundle partners, such as home care service providers, to source solutions that include both the devices and home monitoring technology. Compared to the traditional procurement approach driven by the lowest pricing for the surgical devices, the collaborative approach between the healthcare providers across the patient journey has shown to achieve improved patient outcomes and lowered costs for the health system. [4]

Value could also come from fulfilling value propositions for all stakeholders involved in the patient pathway or aligning the procurement to particular outcomes that should be achieved for patients. The provincial value-based procurement of ICDs is not aligned with a bundle but was instead related to procedure-based funding. However, the initiative has delivered value, not only for hospitals but also for patients, providers, and the broader health system by focusing on the importance of battery longevity for patients as an organizing principle. The lessons learned from the initiative, such as comprehensive physician engagement, listening to patients, and early market engagement, are efforts that can be leveraged to support procurement initiatives for bundled care.

The Benefits of Procuring for Outcomes is Clearly Outlined in the Literature; Why has Ontario Struggled to Mobilize this Type of Procurement at Scale?

There is much discussion about the benefits of moving towards procurement activities that consider the larger patient pathway and associated patient outcomes in the literature. However, the empirical evidence on whether procuring for bundled care has delivered on the targeted quality improvement and cost savings objectives remain scant and inconsistent. [5], [6] In this section, a list of challenges is identified with respect to mobilizing procurements to support bundled care from a SSO’s perspective.

Integrated funding policy is still sufficiently in its infancy to allow for the Ontario supply chain to fully address current procurement silos, such as procuring for the entire patient pathway.

Ontario has only touched the tip of the iceberg on implementing bundled payments, in part due to the complexity of payment models for new conditions. The ministry currently supports a diverse funding model that spans a global portion and patient-based funding elements, e.g., quality-based procedures for hospitals. Ontario’s many funding streams do not allow the hospitals to align all their purchasing efforts with the entire episode of care. The funding mechanism for QBPs was developed based on types and quantities of patients treated for a specific acute care procedure. This funding methodology does not contemplate care that might be required throughout the entire episode, such as home and community care. [7]

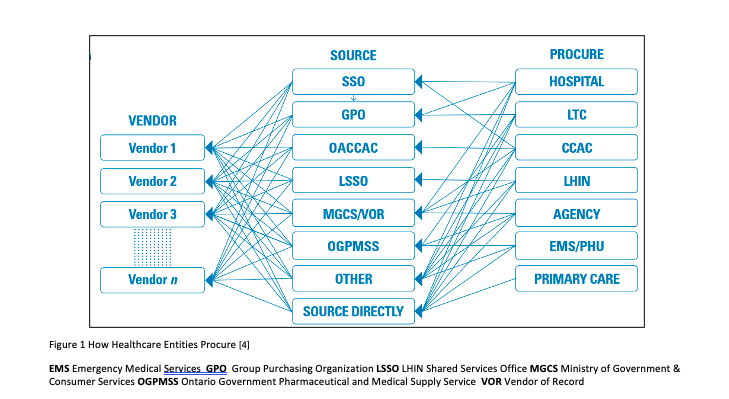

With this in mind, the current procurement model in Ontario has had to remain responsive to the dominant governance and funding structures, which result in highly fragmented and decentralized purchasing decisions. The fragmented decisions are furthered by each care setting — e.g., hospitals, LTC homes, home and community service providers — being supported by their own list of procurement entities.[3](See Figure 1)

Also, there is a diversity of business models within each procurement silo. For example, hospitals can technically procure through a GPO, SSO, government Vendor of Record, and/or their own internal hospital procurement departments. Moreover, procurement continues to operate in response to the dominant funding mechanisms that support more transactional purchasing activities based on annual funding cycles. The procurement approach limits the ability to meaningfully plan for go to market activities that consider a more comprehensive patient pathway and the total cost of care. The siloed funding and fragmented procurement environment have financially incented stakeholders to consider their best interest within a healthcare system that is constantly under financial pressure.

Similar to the mechanism of bundled care, the Ontario government could create an integrated funding policy to enable alignment of the different procurement silos and facilitate more opportunities to consider how to achieve greater financial efficiencies.

It is challenging to measure patient outcomes objectively and tie them to a specific intervention from a vendor. [6], [8]

The success of a VBP is not only measured on purchase price improvements but also defined by achieving value across dimensions that are identified upfront as core value opportunities. Compared to a traditional procurement that focuses on specific requirements and price, it is challenging to define, objectively measure, and fairly evaluate the “value” aspects of a value-based tender. It is even more challenging to reach a consensus on what value is among a wide array of government, health sector stakeholders, and vendors who participated in the VBP initiative.

The basis of a value-based tender evaluation is centered around patient outcomes. Through conversations with vendors, it is evident that they want to provide solutions to improve patient outcomes rather than just providing transactional products and services. However, patient outcomes are usually multi-factorial in a complex patient pathway, making it challenging to attribute any impact of outcomes to a specific vendor solution.

Also, most vendors, unless large consortiums are put in place, cannot be meaningfully embedded in the entire episode of care, making it difficult to deliver much beyond a portion of the patient pathway. Thus, it is often challenging to mobilize a single procurement for the entirety of a bundle, which holds vendors accountable for certain patient outcomes impacting the entire pathway.

When Plexxus engaged vendors on a value-based sourcing initiative, the SSO asked the vendors to propose solutions to improve their product usage on hospital-acquired infection rates. One vendor’s feedback was that any impact on the infection rate could not be directly linked to the performance of their or their competitors’ products. Multiple factors, including the selection of the products, can contribute to variations in the infection rate. Although the real-life example demonstrated the challenge of explicitly tying procurement to outcomes for an acute episode, it is reasonable to believe that procuring for the entire patient pathway could be even more challenging.

Purchasers often have minimal capacity to participate in procuring for the entire patient pathway. [6], [8]

Procurements to support the full bundled episode require a more complex type of value-based procurement. Thus, it requires more time, effort and a more focused contract management approach throughout the life of the agreement to ensure results are being realized. Early and consistent engagement with a substantial number of stakeholders such as healthcare providers, government, and other health system partners is imperative to ensure alignment on the goals and objectives that are being targeted.

More recently, purchasers such as hospitals have had limited clinical capacity to meaningfully invest in VBP relative to patient care and broader health system priorities that the hospitals must also support with already constrained resources. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Ontario hospitals are facing unprecedented capacity constraints to combat the pandemic. Among other competing demands such as resuming non-essential businesses and elective surgeries, preparing for a potential second surge, and assisting long-term care (LTC) homes, procurement initiatives to support bundled care are a lower priority for hospitals, resulting in many instances of direct negotiations and contracts.

In addition, the inability to procure for the entire patient pathway is not just a result of lacking hospital capacity but also the commitment to collaboration. Hospitals often cannot align for complex procurements due to various operating pressures and not being incented to act collaboratively. It is the hope this will begin to change as the province continues to support the implementation of the recent initiative of Ontario Health Teams.

Moreover, recent McKinsey physician surveys suggest that most respondents still do not have a solid understanding of value-based care or payment models. Thus, 21% of those physicians reported that they would be less likely to participate in those care models. [9] Furthermore, clinicians often want to maintain the status quo compared to exploring complex procurement approaches that can disrupt their usage preferences for specific products. As the role of VBP moves away from enabling clinical preference, increasing physician collaboration involves a significant amount of change management, communication, and strong system leadership from the government.

Examples of Early Wins Achieved from the Value-Based Procurement Initiatives Led by Plexxus

Hip and knee replacement bundles

Despite the challenges discussed in the previous section, several Plexxus hospitals have successfully leveraged procurement as a tool to generate greater value within the post-acute portion of the bundle, such as partnering with community service providers to design more integrated service models. In one instance, a procured home-care service model for hip and knee bundle patients helped ensure a seamless transition for those patients from hospital to home using allied health, nursing support, and virtual care while staying under the funded rate. The participating hospitals and the service provider arranged an up-front agreement on how benefits, both quantitative and qualitative, were measured and evaluated over time.

Key outcome measures for the hip and knee bundles, including readmission and length of stay, were established as the basis for ongoing review of project success. A risk and gain sharing model was also put in place to financially incentivize care collaboration and integration across the patient continuum, enabling bundled care implementation. The model allowed for shared savings between the hospital and the service provider where the direct impact was realized, and penalties if the cost per case exceeded the bundled pricing.

Provincial value-based procurement of implantable cardioverter defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices

Even though the value-based procurement for ICDs and CRTs was tied to procedure-based funding, the initiative’s success is the empirical evidence of what a VBP could achieve for Ontario’s healthcare system. The Ministry of Health selected Plexxus to lead the first provincial value-based procurement initiative for ICDs and CRTs. Plexxus worked alongside physician leaders from Ontario’s 12 ICD Implanting Centers, partners, such as CorHealth Ontario and other SSOs, to develop a value-based procurement strategy to increase overall value for patients, and the broader healthcare system. Feedback received from patients such as device longevity, battery life, and MRI compatibility were included as critical considerations for the strategy to improve patient outcomes.

In order to incorporate device longevity into the procurement strategy, a robust longevity analysis methodology was developed to reward longer-lasting cardiac devices that improve patient experience. The approach used evidence-based inputs to support the evaluation of battery longevity. This is critical to moving procurement beyond a short-term decision to focus on the impact to patients over their lifetime. Fewer device replacements are directly related to better patient outcomes and reduced utilization of health system resources.

To support this undertaking, Plexxus established a provincial governance structure to support different elements of decision-making related to the core aspects of the procurement process as well as issues of broader policy and funding. The governance structure brought together clinical, administrative, and health system leadership, supported by a cross-functional team with representation from MOH, CorHealth Ontario, Plexxus, a health economist, and a fairness advisor.

Also, Plexxus developed a multi-phase evaluation approach for clinicians and administrators to meaningfully assess products and services that would address clinical requirements in addition to the hospitals’ business needs. To date, this initiative has demonstrated the benefits of a value-based procurement not only for participating hospitals but also for patients, providers, and the broader health system. It underscores the significant process considerations when designing non-traditional procurements. [10]

Looking Ahead

Ontario’s healthcare system is complex and highly-regulated. Continued efforts to create an environment that can align funding policy with procurement is an important enabler in the transition to a more value-based healthcare system. All healthcare stakeholders, including procurement organizations, aspire to maximize value for Ontario’s health system. However, disincentives and risks inherent from a single-payer system make it difficult for individual stakeholders to achieve better value single-handedly.

The implementation of bundled care will not fully succeed as a transformation activity if the province does not continue implementing integrated funding models at scale. A commitment from the province to scale up bundled care will fundamentally provide additional opportunities for procurement organizations to move away from traditional processes towards more replicable value-based procurement activities. With these building blocks in place, the vendor community can start to accommodate these new approaches by evolving their business models.

Furthermore, Ontario lags behind other jurisdictions when it comes to explicitly incorporating VBP into procurement policy. Ontario’s Broader Public Sector (BPS) Procurement Directive does not explicitly exclude value-based procurement practices. Nonetheless, it lacks clear guidelines to support the implementation of VBP. Through the ongoing evolution of our procurement framework, many stakeholders in the healthcare system could interpret the change in procurement policies as a signal from the government that procurement would eventually be seen as a more formal enabler to the achievement of high-quality care.

For example, the European Union (EU)’s new directive on public procurement encourages the implementation of value-based procurement approaches. [11] The directive also included “most economically advantageous tender” (MEAT) criteria as the procurement guideline for tender evaluation. Contrary to the traditional criteria that are predominately focused on pricing, the MEAT criteria take into account the price-quality ratio while also considering other longer-term costs related to socioeconomic impact and the environment. [11], [12]

In addition to a regulatory environment that supports VBP, a clear government mandate to encourage participation in value-based procurement initiatives is another critical enabler to fully realize the benefits. In the case of ICDs, while a formal mandate was not enacted, the ministry incentivized hospital participation by agreeing to hold funding flat for two years after the contract award. The mandate allows for any efficiencies to be reinvested in the relevant cardiac programs.

As per the structure of all SSOs, Plexxus currently has no direct relationship with the government except through the hospitals they support. As such, the ability to mobilize procurements and provide system leadership that can enable hospital and health sector innovation is often limited. While presently though there are no formal processes for SSOs to table value-based opportunities, Plexxus remains committed to being a strong business partner as Ontario continues its journey to become a more value-based healthcare system. This work will, draw on the organization’s broad supply chain management experience and expertise in value-based procurement.

References

[1] Hellsten E, Sutherland J. Integrated Funding: Connecting the Silos for the Healthcare We Need, C.D. Howe Institute, Commentary No. 463. 2017 January.

[2] Farrell M et al. Impact of Bundled Care in Ontario. International Journal of Integrated Care , 18(S2): A89, pp. 1-8, 2018.

[3] Ministry of Health. Bundled Care (Integrated Funding Models). 2018 April.

<http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ecfa/funding/ifm/>

[4] The Healthcare Sector Supply Chain Strategy Expert Panel. Advancing Healthcare in Ontario – Optimizing the Healthcare Supply Chain – A New Model. 2017 May.

[5] Steenhuis S et al. Unraveling the Complexity in the Design and Implementation of Bundled Payments: A Scoping Review of Key Elements from a Payer’s Perspective. The Milbank Quarterly. Vol. 98, No. 1, pp. 197-222.2020.

[6] Zelmer J. Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Aligning Outcomes and Spending, Canadian Experiences with Value-based Healthcare.2018 August.

[7] Ministry of Health. Health System Funding Reform. 2015 September.

http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/ecfa/funding/hs_funding.aspx

[8] Deloitte. How to eat the Value-based Procurement elephant? A Deloitte point of view.

2018 February.

[9] McKinsey & Company. Physician Employment: The Path forward in the COVID-19 era.

2020 July.

[10] Plexxus, Innovation & Strategic Partnerships. ICD Video Series on YouTube. 2019.

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ypHa7Zjv5Pk&list=PL5EE1nUhb-0rAKgSSAGBzo7_aHrlKT4cM>

[11] Gerecke G et al. The Boston Consulting Group. Procurement – The Unexpected Driver of Value- Based HealthCare. 2015 December.

[12] World Economic Forum. Value in Healthcare – Laying the Foundation for Health System Transformation. In Collaboration with the Boston Consulting Group (BCG). 2017 April.

Notes:

[1] Both QBP and bundled care are new funding models introduced by MOH to link funding with quality. Bundled care is an evolved model, expanding on QBP funding methodology, which funds the entire patient pathway and aligns incentives with patient outcomes. QBP is a volume-based payment that aligns with funding for acute care procedures. Also, QBP clinical handbooks were developed by multi-disciplinary expert panels to include metrics, best practices, and evidence-based pathways for select patient populations. Some of the QBP clinical best practice recommendations were used to define the components of patient pathways for bundled care.

[2] VBP is a new procurement approach that incorporates the principles of value-based healthcare. Rather than focusing only on the lowest possible price, VBP focuses on procuring products and services that bring the greatest value to all stakeholders. The value is measured as the best outcomes at the lowest total costs over the full care cycle.

[3] Historically, local health integration networks and community care access centers also had unique procurement requirements, which now have been absorbed by Ontario Health.

The Long Fix: Solving America’s Healthcare Crisis with Strategies That Work for Everyone

Vivian S. Lee, Verily Life Sciences

Contact: vivianlee@verily.com

Abstract

What is the message?

U.S. healthcare needs multiple changes to be more effective: (1) pay for results, not action; (2) run healthcare delivery systems like businesses competing to deliver better health at lower costs; (3) demand that other health industries also compete on making people healthier at lower costs; and (4) learn from the successes of employer-driven and government-run health systems. Several successful ventures provide examples of how to do so.

What is the evidence?

The ideas are based on a recent book by the author, who has extensive experience in multiple U.S. healthcare systems.

Submitted: July 21, 2020; accepted after review August 6, 2020.

Cite as: Vivan Lee. 2021. The Long Fix: Solving America’s Health Care Crisis with Strategies That Work for Everyone. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI.org), Volume 6, Issue 1, Winter 2021.

The Miami Miracle

Chris Chen grinned as he remembered how people raved about his father’s clinic in Miami. His dad had scrambled to set up the clinic in the early 1990s. At the time, a few insurance companies were experimenting with new ways to pay doctors: giving them a fixed amount of money per patient, per year, no matter how sick a person was or became. If a patient needed expensive imaging studies, costly drugs or long hospitalizations that added up to more than that, it was the doctor’s problem.

Chris’s dad and mom—she was the office manager—opened their doors to patients in these new plans. They weren’t very busy, so they welcomed referrals. Other doctors sent them only their frailest and poorest patients, the ones they knew would be “grossly unprofitable” under this new way of paying. That’s how Chris’s parents began with 250 of the sickest people in Miami—people who would have been almost impossible to care for at any facility, at any price. It looked as if the Chens had signed up for a financial suicide mission.

Because resources were scarce and the patients needed so much, the Chens focused on primary care and prevention. These were fragile, elderly men and women who needed to be seen frequently by doctors—once they got sick, it would be too late—so monthly visits were set up, even if there was “nothing wrong.” Just getting to the clinic would be tough for many of them, so the Chens decided to provide free door-to-doctor transportation; they worked out that averting the cost of just one ambulance ride and hospital stay could pay for a year of shuttle service. A pharmacy was installed in the clinic so patients could conveniently, cheaply and reliably fill their prescriptions. And since elderly, frail, and poor people have an array of issues which make caring for them extremely complex, physicians in the clinics met several times each week to analyze how best to treat those who weren’t doing well.

Somehow, that “crazy Chinese doctor” and his wife not only gave outstanding care to all those seemingly hopeless cases—even those who couldn’t didn’t have enough money to pay their co-pays or deductibles—but they also managed to make them healthier. In fact, they reduced hospitalizations to one-third the expected rate. Even more amazing, they were able to break even financially. Simply, the Chens invented a better way to care for the elderly… and the rest of us.

The Fundamental Flaw

Healthcare is killing the economy, and in too many cases, killing us.

The system is bloated, wasteful and sometimes even dangerous. It is bad for patients, bad for doctors, and bad for business. For most Americans, the rising costs claim too much of their disposable income, and for most American companies, they are ravaging their bottom line. Beyond the outrageous cost of this care is its wildly varying quality. We all know from painful personal experiences that healthcare in this country delivers too few miracles and far too much stress, emotional and financial. It often seems as if no one is driving the bus, or that those at the wheel—doctors, hospital administrators, insurers, politicians—are swerving out of control.

Most of us trapped working in this system are desperately hoping for a better way. Many of us have successfully changed our practices to tackle important problems. For example, at Utah we created innovations like special catheter dressing kits that slashed the rate of blood infections in our burn care unit to zero. We also asked for patient feedback on all physicians, then posted all those comments online, and created a price transparency website so patients could estimate their out-of-pocket expenses.

Those changes and many others made us the safest teaching hospital in the country. In 2016, the University of Utah was ranked #1 in the nation among university hospitals for delivering the best care for our patients—the seventh straight year we made the Top 10.

Having interviewed hundreds of patients, clinicians, insurance executives, policy experts and journalists, I discovered real and practical solutions for how we all, working together, can build a safer, better, and cheaper healthcare system. Whether it’s frontline community health workers and patient families in Cincinnati, state employee health plan leaders in Washington state, palliative care doctors in Albuquerque, or the Chens of Miami and beyond, there are stellar examples all over this nation that prove it.

You may ask: If these leaders are improving the health of their communities, why aren’t their successes spreading more rapidly across the nation?

We Usually Pay For Action, Not Results

We all have to tackle the central and essential obstacle that is preventing real progress at a national scale.

This is the fundamental insight: The root cause of our maddening mess—inconsistent and unsafe care, unintelligible medical bills, inscrutable insurance plans, and inexplicable drug prices—is that insurers and government programs like Medicare and Medicaid pay for action, not results. They pay for every pill, MRI, lab test and operation, whether or not any of that makes us healthier. This arrangement has spurred massive growth in the industry and also generated an obscene amount of waste, from countless unnecessary operations and procedures to ever-more-expensive drugs that don’t work any better than generics. When people are compensated for doing something, independent of the results, they tend to do more and more of it. The primary motivation becomes getting paid, which may or may not get you healthy. That’s backwards and dangerous.

ChenMed Solution: Paid for Results, Delivering Results

For most doctors, it feels wrong to overtreat, to focus on profitability at the expense of health, and many of us are frustrated and even burned out. We want it to be different. Dr. Chen and his wife understood this. Their son, Chris Chen, who is now ChenMed’s CEO, has introduced this model of care into more than 50 primary care medical groups for seniors in Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania. At ChenMed clinics, instead of signing up as many patients as possible, which is the only way to support the fee-for-service (pay-for-action) model, physicians have fewer patients and spend more time with each of them.

Most primary care doctors in the U.S. handle over 2,000 patients; a ChenMed physician has between 450 and 600, which means they get to know the people in their care. Dr. Sofia Recabarren is a primary care physician who sees patients at a ChenMed clinic in Miami. She treasures the 40 minutes allotted for each new-patient visit and the 20 minutes for follow-up appointments, compared to half the time in her old job in New York City. “You actually know their meds,” she says. “You know what’s going on in their lives.”

That extra time matters. A lot. Chris Chen told me about a 400-lb. woman who, whenever she was asked what she had consumed for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, always gave answers which suggested she was eating sensibly. Chen was baffled over why she seemed unable to lose weight. One day, the woman’s daughter accompanied her mother for a follow-up visit. She thanked Chen for continuing to try to help her mom and then asked, “Can you get her to stop eating that bucket of KFC at midnight?”

Like all of the other physicians at ChenMed, Sofia Recabarren’s and Chris Chen’s goal is to keep their patients out of the hospital. One good way is to reduce the risk of falls and broken hips, instead of profiting from them. That’s why Dr. Recabarren has her patients take a short class to test how well they can see, checks their balance, makes sure their shoes fit well, and even gives tips for staying hydrated. She also encourages her patients to sign up for the clinic’s free Tai Chi course.

ChenMed clinics also understand that a person’s well-being is inextricably tied to overall health. They host monthly birthday bashes for patients—yes, their vans will bring you to this popular event and take you home after you’ve had your fill of cake, dancing, and gossip. These doctors know that loneliness is a killer. All over the world, physicians are starting to understand this and beginning to treat social isolation as a disease. In 2018, the British government appointed its first “minister for loneliness” to address isolation for citizens of all ages.

Other Examples

Physicians across the U.S. have adopted similar approaches to caring for patients in medical groups like Caremore, Leon Medical, Iora Health, and Oak Street Health, and ranging from California to Illinois to Massachusetts. They know it’s a better way to do medicine, and it’s also a better way to do business.

Studies show that ChenMed lowers the number of days patients are in the hospital by 38%. Same-day clinic visits mean that the number of expensive emergency department visits also drops. Chris Chen says clinics like his see at least a 25% increase in profitability. This model is so successful that Medicare has adopted it for its Medicare Advantage program. As an alternative to the regular Medicare program for seniors, Medicare Advantage is allowed to contract with doctors to pay them a fixed amount for keeping patients healthy. It is popular with seniors and projected to enroll over one-third of all Medicare patients in 2020.

The profound lesson learned by Chris Chen and his parents is that it’s far more effective to care for people before they get sick. And cheaper. That’s great news for those patients, but most of the U.S. is still paying an exorbitant penalty for ignoring that wisdom. Promoting health saves lives and money.

The Maddening Paradox: Best and Worst Health Care

By a few measures, the U.S. health care system is one of the best in the world and, by other measures, it is one of the worst.

The United States leads the world in medical innovation, and its scientists are discovering new cures at an exhilarating pace. The delivery of care, however is wildly uneven. Hands down, the United States spends more on healthcare per capita than any other nation— nearly one-fifth of the U.S. economy goes to pay for health. That’s two to three times more than other high income Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nations like the UK, Canada, Germany, Japan, and Australia, where health coverage is universal. Despite this about 1 in 11 Americans do not have health insurance and can’t afford care.

While most of the rest of the world is getting healthier and living longer, life expectancy in the United States is declining or, at best, flat. Babies born in the United States in 2017 are expected to live 78.6 years, 5.6 years less than those born in Japan, which places us 26th out of 35 OECD nations in life expectancy. The prospects for a healthier future are rapidly fading: Four out of ten adults are obese, and seven out of ten are overweight, making them much more likely to suffer from back and joint pain, and, over time, to be stricken by heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer.

The nation is paying dearly for these failures. Companies that cover employee health insurance have seen rising costs that erode their margins and hobble competitiveness. Much of that ever-rising expense has been passed on to employees, often in hidden ways like flat wages over the past 50 years. Workers are also getting hurt directly, as deductibles and co-payments soar.

Healthcare is bankrupting the uninsured and the swelling ranks of the underinsured, and it’s often disappointing the millions who do have coverage. This ailing, failing system is making our nation sick— financially, emotionally, and physically. But within this seemingly barren healthcare crisis is not a spring but practically an ocean of opportunity.

Stop Paying More For Less

Reduce Expenses Not Care

With healthcare spending rapidly approaching $4 trillion per year, the obvious but misguided solution would be to reduce expenses by cutting care, but that’s dangerous for patients and for our future. It’s not care that needs to be cut, it’s the wasteful spending that doesn’t contribute to better health. We have to stop paying more to get less.

First and foremost, we need to reduce the waste. The Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Medicine) estimated in 2012 that we waste 30 cents of every dollar we spend on health care. That’s over $1 trillion per year. Some of the waste is fraud and abuse, but most of it comes from failures to care for patients properly.

A substantial part of the waste is driven by overdiagnosis and overtreatment. In a 2016 survey, U.S. physicians concluded that about 20% of all medical care was unnecessary.

Additionally, ever driven to diagnose more ailments and perform more procedures, we are making deadly mistakes. Medical errors are the third-leading cause of death in the United States— over 250,000 deaths each year. That’s about 9.5% of all deaths, behind only heart disease and cancer. Many of the mistakes come from the inconsistent application of scientifically-derived guidelines. Physicians follow recommended guidelines only one- half to two- thirds of the time.

Besides the way we practice medicine, we are also choking on bureaucracy. In the United States, about 8% of spending on health care is spent on administration. Among ten high-income OECD nations, the figure averaged only 3%. Much of the bureaucracy burdens healthcare professionals who are paid generously but waste a lot of time. These expensive professionals waste a large percentage of their time on frustrating administrative tasks like computer data entry and disputing with insurance companies instead of caring for patients.

Because they generate the highest fees in a fee-for-service business, new technologies and treatments get advanced ahead of cheaper or generic alternatives. We spend double to triple what Canada and some European countries do on pharmaceuticals, mostly due to high-cost, branded drugs and the over-prescription of antibiotics and other medications. Prevention and primary care often are demoted in favor of specialty care.

Even at the end of life, we overtreat and overspend. We deny the wishes of the dying. We put people in hospitals who would be better off at home. In the hospital, we attach them to costly life support systems, even when they have asked to be left alone. While four out of five people would prefer to die at home, only one out of five does. Most people still die in a hospital or nursing home.

We are spending plenty, but not always in the right ways, and without getting what we want or what patients deserve.

Demanding Results not Action

Even those who are succeeding in the current fee-for-service model realize that paying for results— better health outcomes at lower costs— would radically improve our system. If our nation stopped expecting quick fixes— a prescription, a referral to a specialist, an MRI, an operation— and instead put a premium on measurably improving lives for good, then prevention would become paramount.

The medical world would focus on diet, sleep, and fitness. We would make restoring mental health as important as restoring physical health. We’d try to prescribe only drugs that work and that do so cost-effectively. We’d recommend imaging studies or operations shown to be beneficial. Back operations, for example, would be reserved for the few who truly needed them, and everyone else would be told to rest or undergo physical therapy. Hospitals and clinics would standardize care, making it safer and better. And those who didn’t would go out of business.

Who Cares? I Have Insurance

If the answer is so clear, then why isn’t the nation moving faster to paying for results?

For one, many have a vested interest in the status quo. Maybe even more important, most of us don’t really buy healthcare, we buy health insurance.

That means we don’t pay for healthcare directly, we pay for it indirectly, and even that is often subsidized. For about half of Americans, employers pay for most of their healthcare. For others, healthcare is a government benefit paid for by taxes. Only the 8.5% of Americans who remain uninsured pay for their healthcare bills directly—and mostly they can’t afford them.

With this insurance-based model, the dynamic between insurers and doctors can put them at odds with patients’ interests.