Dmitry Krass, Sydney Cooper Professor of Business Technology, Professor of Operations Management and Analytics, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Abstract

Contact: krass@rotman.utoronto.ca

What is the message? This article contributes to the debate on what forms of social distancing policies will be most effective in addressing the health and economic impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. Strict social distancing measures, such as those being used in Italy, elsewhere in Europe, and North America, may lead to unfortunate trade-offs in health and economic well-being, with excessive economic stresses leading the even larger damages to health. By contrast, milder social distancing policies, if combined with strong policies of testing, quarantine, adopting face masks, protecting high-risk groups, safety in public places, and economic recovery, may be more effective in supporting both health and economic welfare.

What is the evidence? Basic cost-benefit analyses, using assumptions based on the recent trends of the coronavirus pandemic.

Timeline: Submitted: March 26, 2020; accepted after revisions: March 29, 2020

Cite as: Dmitry Krass, 2020. Why are We Emulating Italy Instead of South Korea? Health Management, Policy, and Innovation (HMPI.org), volume 5, Issue 1, special issue on COVID-19, March 2020.

High-Risk Response

The response by most governments and public health authorities in the West to the coronavirus pandemic has been guided by the gospel of “social distancing”: essentially freeze all social interactions to “stop the virus in its tracks”. Whole industries (airline, tourism, food service, non-food retail), as well as most educational institutions (schools, universities) have been shut down indefinitely, until evidence that growth curve has been “flattened” is at hand.

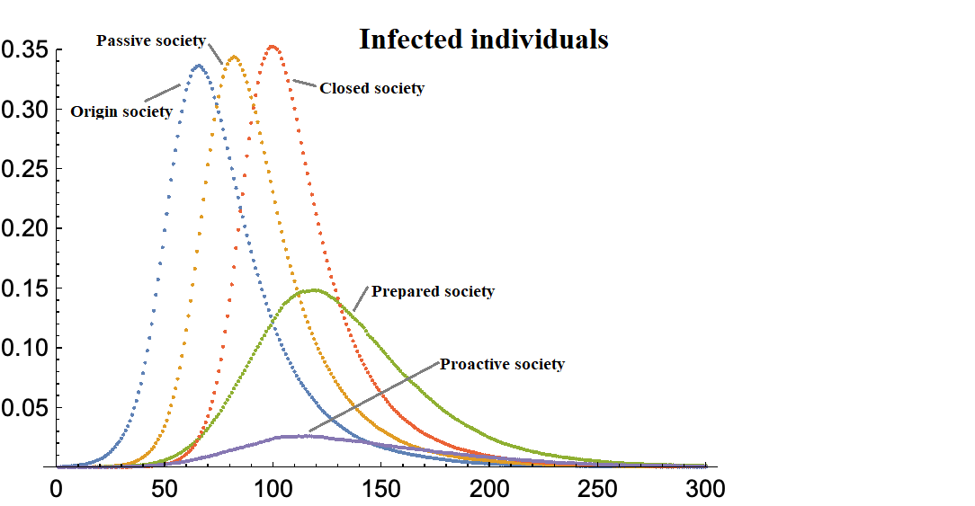

One should distinguish between different types of social distancing measures; for lack of better term I will refer to them as “mild” and “strict”. Mild measures are largely voluntary for the general population, while including far stricter policies for known and suspected infection carriers, as well as high-risk individuals. They also include low-cost transmission reduction measures such as wide adoption of face masks, surface cleaning, disposable gloves, as well as cancellation of large-scale events where close personal contact is likely. The vast majority of economic activity is allowed to continue functioning under this model.

Strict measures are very different. They include major infringement of the most basic individual rights (freedom of movement, freedom of assembly, freedom to earn a living) applied to all of the country’s population[1]. The goal is to stop most social interaction, with the accompanying shutdown of large portion of the economy. This has become the new norm of response to the COVID-19 pandemic in North America and Western Europe.

Multiple Aspects of the Social Distancing Responses are Striking

The policies are largely untested. While there is some empirical evidence in the literature indicating that social distancing measures can reduce the number of cases and/or delay the occurrence of the peak of infections (“flattening the curve”), nothing even approaching the scale of economic shutdowns seen today in US, Canada, and most West European countries has been tried before.

The closest case is China’s actions in shutting down the city of Wuhan and imposing various restrictions in Hubei province during January-March, but even these pale in comparison: only one region of the country was affected by the most severe restrictions, and much of the economic activity continued in the rest of the country. The documented instances of social distancing in the literature (dating back to 1918 and 1950’s) were far more limited in scope, including only school closures and event cancellations. Nothing approaching nationwide shutdowns of major industries, wide-scale travel restrictions or stay-in-shelter orders have been tried. The fact that large-scale social distancing is unprecedented flies in the face of the narrative one hears from the media, where such policies are presented as the only reasonable approach, based on scientific truths and accepted practice.

The truth is closer to something like this: We have an idea for a medicine that works well[2] in our theoretical models, and something similar to this medicine saw limited usage some time ago; let us now make it absolutely mandatory for everyone to take. In any other context, this would be irresponsible – so how is it responsible to roll out “shelter in place” and “no non-essential businesses operating’’ policies, that have never been tested before, both with respect to their benefits or harm, across the Western nations?

One is struck by the dichotomy: on the one hand we have several promising vaccines for COVID-19; the early results are promising and human trials have started, but, of course, the vaccine cannot be approved by the FDA until large-scale trials are completed: after all, it may be administered to millions of people and it would be irresponsible to approve it before possibly dangerous side effects are known. On the other hand, when it comes to untested ever-escalating draconian measures with open-ended economic consequences, no such prudence prevails: it is regarded as irresponsible not to implement them.

It appears that costs massively outweigh the benefits – likely by orders of magnitude. To the best of my knowledge, no attempt at cost-benefit analysis – which should be the starting point of any large-scale economic intervention – has been done. The positive impact of the social distancing measures is very uncertain. As pointed out by Prof. John Ioannidis, a prominent epidemiologist from Stanford,[3] we do not have nearly enough data to estimate the potential benefits.

On the other hand, the scale of the economic damage they are wreaking is open-ended: estimates range from 10% reduction[4] in GDP to possible shutdown of whole industries; an airline that is not flying or a hotel that is not operating are hard to keep afloat, even with government help. Note that the 2008 financial crisis resulted in 3% GDP loss, but did not involve the shutdown of whole swaths of the economy.

Many people have already lost their jobs – and we are just days into the strictest measures in North America. Massive additional job losses are expected. The sectors of the economy hardest hit (food service, retail and tourism) also employ disproportionate number of lower-income workers; even a short-term interruption in income is likely to push many people below the poverty line. And all ills of poverty, including serious diseases and shorter lifespans, are sure to follow.

Thus, even ignoring the financial aspect and focusing purely on life-years saved, there is a clear trade-off between the benefits of “social distancing” measures and the economic devastation they will cause. One should add to the health costs the increasing mental stress and anxiety social isolation will cause, with lower-income earners living in cramped accommodations hit hardest. These effects should not be dismissed – solitary confinement in prisons is regarded as a harsh form of punishment, reserved for worst offenders; we are inflicting this on the whole society.

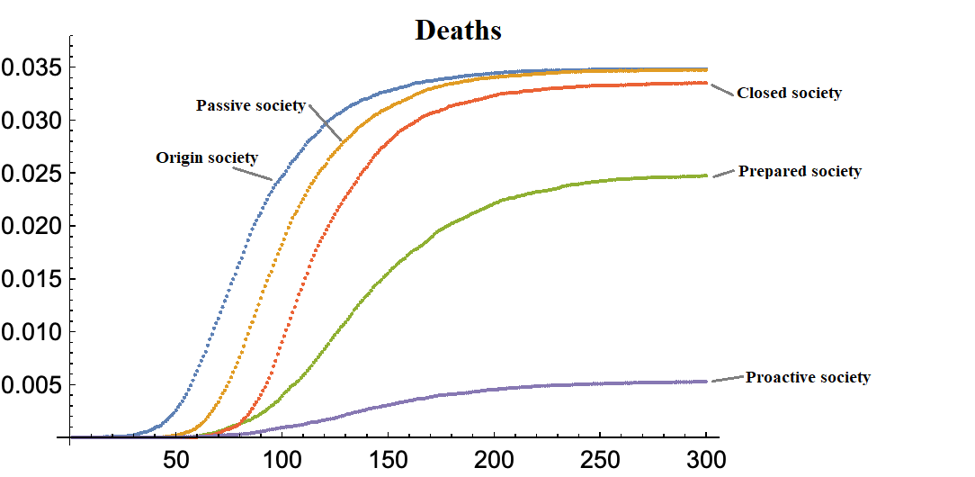

Will the benefits outweigh the costs? The answer is likely “no”: as pointed out by Ioannidis, the current best estimates of the infection fatality rate[5] are very uncertain, ranging from those not much higher than for seasonal flu, to those five times that amount. Surely, when one is inflicting a massive economic burden on millions of people, is such analysis in order?

Yet, not only has no such evaluation appear to have been performed, even suggesting it seems to be regarded as callous and unpatriotic. In a rejoinder entitled “We know enough now to act decisively against COVID-19. Social distancing is a good place to start”[6] to Ioannidis, Prof M. Lipsitch, a no less eminent epidemiologist from Harvard, does not dispute any uncertainties, but merely states that the current course of action is the only choice. One cannot help but wonder if shutting down the economy is a “good place to start”, what is the intended finish?

Even very rough financial estimates show that the current measures are massively ineffective – by orders of magnitude. Take Italy as an example. Between February 24 and March 8, in a series of rapidly escalating steps, some of the most stringent social distancing measures ever were adopted. The whole country was placed under strict travel quarantine; all schools, universities, public venues, and most stores were closed; police began patrolling railway stations and threatening to arrest anyone attempting to travel without a permit, etc. Sadly, these measures are no longer unique: since March 8 many countries have followed suit, and the measures that seemed straight out of some horror movie at the time now look quite commonplace.

As of this writing (March 25), Italy has recorded just over 7,500 COVID-19 deaths, with the number of new cases and the number of deaths appear to have peaked around March 20. The median age of death is around 80 years old. Let’s assume there will be further 7,500 deaths, for a total of 15,000 (an incredible number – this would be 250 deaths per 1M population, vs 2 in China, 2 in South Korea and 0.5 in Japan – all of which appear to be at the tail end of the epidemic).

Let’s generously assume that without strict social distancing measures the number of deaths would be double – a very optimistic assumption as there is little actual evidence that the disease trajectory or the death rate was substantially reduced at all since these measures came into effect. Note that we are not comparing strict social distancing with the “do nothing” scenario – no responsible government would contemplate the latter. Rather, we should be measuring the marginal effect of the economically costly strict social distancing measures vs their “mild” counterparts, described in more detail below).

Using the standard actuarial tables, someone who survived to age 80 has a remaining life expectancy of around 8.5 (males) – 9.5 (females) years. To keep math simple, I will round it up to a 10 (another generous assumption, as most of those dying also have other underlying health conditions). While it seems callous to value a life, policymakers have to do it all the time; a common range of $7-$9M appears to be (e.g., US Environmental Protection Agency uses $8M). With the average lifespan of 90 years (again, rounded up), this works out to $100K per life-year (a likely overestimate). Thus, strict social distancing may have saved a maximum of 10*$100K*15,000 = $15B.

Now let’s look at the cost side. Italy’s per capita GDP in 2019 was $33,156 and the population of 60.5M. Assuming 10% GDP loss[7], this works out to $2,008B – a figure roughly 135 times higher than savings. Put it another way, social distancing would have to prevent over 2M deaths to make costs roughly match the benefits. Applying the same simple calculations to other countries – US, Canada, etc., – leads to numbers that are even more outlandish. The costs exceed the benefits by astronomical amounts[8].

One can of course dispute some of the assumptions above, but when the differences are this large, precision is not the point: for example, even if the GDP loss is only 1% (a figure suggesting that shutting down the economy for weeks is equivalent to a mild economic downturn; e.g., Italy saw a 2.8% GDP loss in 2012 and 5.5% in 2009), the benefits are still 13.5 times lower than the costs.

We are told that the reason we need to “stop the virus in its tracks” by implementing the draconian measures is to ease the burden on our strained medical system – already operating near capacity, it will break under the flood of new cases. But what about our strained economies? The current measures may well have catastrophic effects. One must remember that it is countries with strong economies that can afford strong medical systems, not the other way around. The current policies seem akin to advising someone whose house is on fire to jump into a swimming pool and hold their breath until the fire abates – a 100% effective approach to escaping the fire danger, but hardly a practical survival strategy.

Any time the costs and benefits are several orders of magnitude apart, the policy can only be classified as unsustainable. One should look for alternatives – something, perhaps, less “effective” but also less costly. Continuing with the house fire analogy, perhaps you can jump into the swimming pool and tread water; sure, this is less effective in terms of preventing fire risks – you may still be hit by flying cinders or inhale some smoke, but you will also not replace the burn risk with the certainty of drowning.

The policies are untargeted. The current measures apply to everyone within each region, with some relatively minor differences in severity from region to region. This is only warranted if (1) you do not know who is likely to be transmitting the virus, and (2) you do not know who is at high risk should they get infected. Presumably, if you could identify the likely carriers of the disease, you could isolate just them. And if you knew who was likely to be at the highest risk, you could set up a protective system around just them. The rest of the population could go on with, more or less, their regular lives (subject to mild mitigation measures, such as wearing a face mask, described earlier).

In 1918, when (much more limited) social distancing measures were first tried, both (1) and (2) were true, so universal application of policy was understandable. But this was over a century ago! Neither (1) nor (2) are true today: we do know quite a bit about both carriers and risk groups:

- We have tests to identify infected individuals. Massive testing, that was implemented in South Korea and that is now being rolled out in North America can identify infected individuals early (during the so-called pre-symptomatic stage).

- We know the mode of transmission: the infection spreads by droplets (produced while talking or coughing) and fomites (infected surfaces).

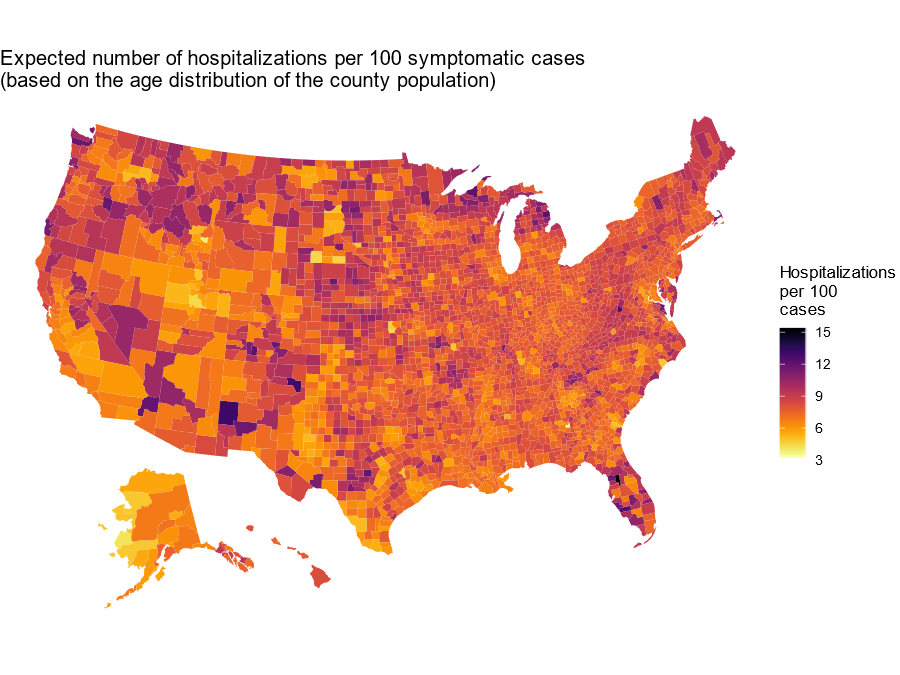

- We also know who is in the inflated risk group: those over 65 and/or people with prior serious health conditions.

However, none of this knowledge is reflected in the current policy: my 83-year old mother-in-law is under exactly the same restrictions as me and my wife who are in our mid-50s, and my 20- to 25-year-old students. Recently, my friend’s daughter tested positive for COVID-19 after exhibiting mild symptoms. Public health authorities directed her and her contacts to self-isolate for 14 days. This is only slightly different than the advice given to the rest of the population in Toronto. In fact, had she lived in many US states, where the population is already under the “stay-in-shelter” orders, there would have been no difference at all.

Limited testing capacity was a huge constraint in the early weeks of the disease spread in North America. With great effort, and at great cost, this capacity has been rapidly expanded – still short of where it needs to be, but far better than a few weeks ago. But if knowing who is and who is not infected has no sizable impact on policy, this effort was largely wasted.

The rejoinder one hears against targeted approaches is the uncertainty: we still have very limited data and many unknowns remain. Does transmission happen only via droplets, or is aerosol (droplets suspended in the air) infection possible? How safe are younger age groups without pre-existing conditions? Somehow, the more serious uncertainties regarding the economic consequences of the current policies are dismissed.

Our focus should not be on 100% certainty or 100% effectiveness; we should instead be looking for policies that are reasonably effective and come at reasonable costs. If implementing various mitigation strategies, isolating the likely carriers, and protecting the likely high-risk groups achieves 80% (say) of the effect of the current policies at the costs of billions rather than trillions, the cost-benefit calculations may become more in line. It is well-known in management science that costs may increase astronomically as one tries to come closer to 100% reliability in a system with inherent uncertainty.

Simple low-cost solutions are eschewed in favor of massively expensive ones. If one looks, side by side, at two recent photos of a busy downtown street (back when our downtown streets were still busy), one from any major Western city (e.g., Toronto or London) and one from any major Asian city, what is the first difference that jumps to mind? I am sure it is the face masks (“surgical masks”): on the Asian photo everyone is wearing them, while on the Western one almost nobody is. In fact, in many places in Asia, appearing in public without a face mask, is regarded as a violation of social norms: callously putting people around you at risk.

In the West, particularly in North America, there has been a tremendous, and very effective[9], public campaign against wearing facemasks as the number of cases of coronavirus initially started to spread – we were told by a variety of public health authorities (including the CDC), and in countless interviews on TV, that face masks are not effective for preventing the illness, that they can even be dangerous, they should be avoided, etc. Instead, we were told[10] to cough or sneeze into an elbow (presumably having a sleeve full of droplets that may rub off on surfaces is quite safe).

This advice flies in the face of common sense, scientific knowledge[11], and the experience of anyone showing up with a cough to emergency room or COVID-19 testing center: the first thing you are handed is a face mask; this is before any testing takes place. The logic is clear – if you are infected, you are a danger to others, and a face mask cuts the risk of you infecting others via droplet production by 80% or more (the protection it imparts to you from being infected by others is much lower, but still quite significant – perhaps reducing your own risk by 20%). Thus, if you are a potential danger to others after crossing the threshold of the testing center, were you not just as dangerous before? Or after?

Why am I focusing so much on a humble face mask? Because this is a perfect example of a simple, low-cost solution that, while not perfect, cuts down the probability of infection dramatically. If indeed an 80% reduction in the probability of being infected by a known or probable COVID-19 carrier can be achieved by simply slapping on a face mask, would this not be the first step any responsible public health authority should consider? If instead of focusing on PR campaigns against face masks, efforts were focused on building up stocks and production capacity[12] of this rather low-tech device, perhaps some of the current draconian measures could be avoided?

The only reasonable explanation I can think of for the advice not to wear a face mask was to prevent shortages and save masks for health professionals. If so, this is a rather incredible testimony to the ineffectiveness of the initial response: instead of working with the industry to massively increase the production capacity during January-February of 2020, the decision was made to provide obviously misleading information to the public. The message is being reinforced every day – while Asian public figures are wearing face masks during their press briefings, reinforcing their importance to the general public, North American and Western politicians never wear them during public appearances.

Other natural low-tech solutions abound. Hang packs of tissues next to door handles and elevator buttons in public spaces to minimize surface contact. Urge restaurants to use disposable plastic sheets as table and chair covers. Encourage people (particularly members of high-risk groups) to wear disposable gloves, goggles, etc. Would these be 100% effective? No! But they could significantly cut the chances of transmission/ infection at negligible costs.

Response Model: South Korea or Italy?

There seems to be two prevailing modes of response to COVID-19 pandemic; for ease of reference I will dub them “Italian” model and the “Korean” model.

Italy: The Italian model largely follows the escalating steps of economic shutdown and social distancing described above. It seems to be patterned on the steps taken by China in Hubei province (so perhaps calling it the “Chinese” model is more accurate), but Italy has taken it significantly further, shutting down the whole country, rather than just one region. Most countries in the EU seem to have adopted a version of the Italian model. The US appears to be taking it further still, issuing “shelter in place” orders for ever-increasing number of states, so perhaps we will soon be calling it the “American” model.

South Korea: South Korea, on the other hand, has followed a tightly targeted approach[13], focused on deploying large-scale testing to identify the infected individuals early, preventing them from infecting others through tightly-enforced quarantines, voluntary and inexpensive social distancing measures, and almost universal use of face masks. Schools, universities, eateries, and stores remain open, no significant travel restrictions on the citizens have been imposed (though there are tight controls on the incoming traffic). A similar model has been adopted by Singapore, and Taiwan.

Hybrids: Some countries, e.g., Japan and Sweden have followed a “hybrid” approach. These involve closing some schools, universities, tourist attractions, as well as canceling some events, but keeping businesses largely open.

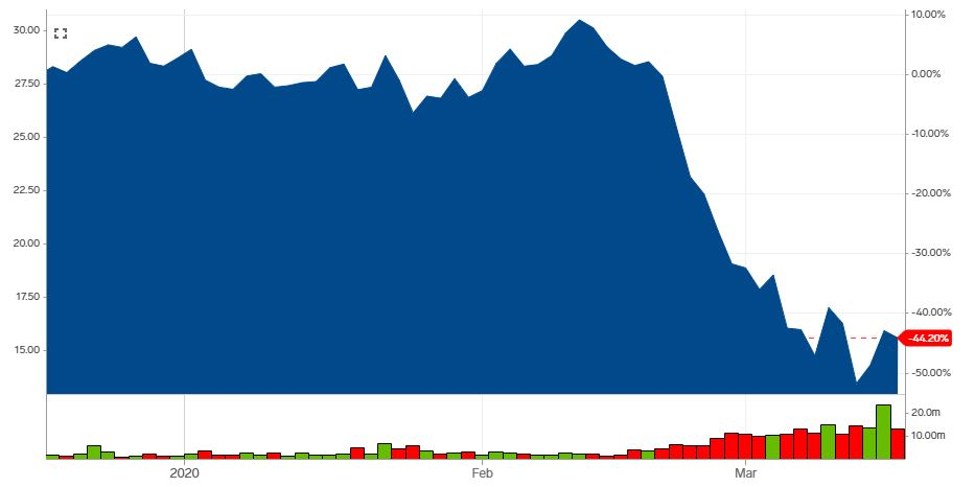

Comparing the models: So which of the two prevailing models should a country follow? By now, the results are well known; I summarize them on Figures 1 (cumulative daily cases, log scale) and 2 (new daily cases, linear scale) below[14].

The yellow line on both Figures is Italy. In spite of the extreme measures described above, the total number of cases is second-highest after China, and the number of new daily cases remain stubbornly high (though, thankfully, leveling off in the last few days). The CFR (case fatality ratio, number of deaths over the number of cases) is 10.9%, the total number of deaths per million is 124, and the medical system is overwhelmed dealing with 3489 critical cases. Most other Western countries (solid lines on Figures) seem to be following roughly the same pattern as Italy.

The dashed blue line (South Korea) behaves markedly differently: the number of cases levelled off just under 10000, the growth rate of the number of cases is near 0, the average daily number of new cases is steady at about 100, CFR is 1.1%, the number of deaths per million is 2, and there are only 59 critical cases. In short, while all the other countries in the chart are still struggling with bringing the epidemic under control, South Korea seems to have done so.

Given this drastic difference in results, the expected take-away would be: let’s avoid the Italian model, and adopt the Korean one as soon as possible. Instead, and quite amazingly, the lesson learned by the policymakers seems to be entirely different: look at what a horrible mess Italy is in, even though they took all these drastic steps; unless we adopt even stronger measures, things will be even worse here. Thus, the Italian experience is used to justify the ever-more draconian measures, while the Korean approach is only mentioned in passing (“they too adopted some social distancing measures”).

Why is the Italian model less effective? The question of why the Italian model of response has been so much less effective than the Korean one is quite interesting and deserves in-depth study (on would expect South Korea to be crawling with public health officials from all over the world trying to find the answers; however, I suspect, this is not the case). Why have strict social distancing measures in Italy largely failed, while far milder ones in South Korea proved successful?

A possible answer lies in the observation in the WHO report that most infections in China happened within families (family attack rate was up to 10%), while community spread was not a key source of new infections. Forcing families to stay together in often cramped accommodations increases the social distance between households, but certainly decreases them within, which may lead to higher infection rate, particularly if new infections are not detected early (there is evidence that the most virus shedding happens during the earliest stages of the disease).

This is, of course, just a hypothesis. One thing is clear; however: expecting Italian-style measures to result in quick wins or “flattening the curve” is not realistic. What is being bought by paying the enormous economic price is not clear.

Take-Aways: Targeted and Sustainable Response

I believe it is imperative that we, in North America, move away from the Italian model, which is, at best, of limited effectiveness and is economically unsustainable. Instead, we should move towards the Korean one as expediently as possible. The overriding principles should be: adopting actions that target the response to the disease and inexpensive measures that limit the transmission of the infection, while avoiding large-scale untargeted ones that damage the economy.

What are the specific steps that should be adopted? The list below is far from complete, but seems like a good start.

- Early and massive testing. This is the lynchpin of the Korean model and must be the centerpiece of the North American one. After some initial missteps, great progress has been made in rolling out a network of testing sites. We are not yet where we need to be: testing is still limited.

As mentioned earlier, by the time the fever sets in, the most infectious phase may have passed, so ideally testing should extend to anyone who has developed a dry cough. In addition, in order to minimize the spread of infection, the results of the test must be available quickly – within hours (in South Korea they are often available within minutes). At the moment, depending on the test site, it is more likely to take days[15]. Thus, both the availability of testing and the speed of evaluation must increase. However, testing is only useful if it guides targeted response; if the current policies are continued the main value of testing is lost.

- Effective quarantine of positive cases. Self-isolation at home may not be the best model: for those living in shared accommodations there is a very high danger of infecting members of the household (sadly, by the time someone is displaying symptoms and is tested, members of the household are likely already infected). It is not reasonable to expect someone to stay shut-in for 14 days – they must go out to get food, dispose of garbage, etc. In the process, they may infect surfaces (door handles, elevator buttons, etc.). Hotel-style quarantine centers, where infected individuals with mild cases can be safely monitored and isolated may be a better idea. In general, monitoring of individuals who have tested positive must be quite strict – another lynchpin of the Korean model, that employs electronic tracking coupled with stiff penalties to enforce quarantine orders.

- Wide adoption of face masks. Until the epidemic is well under control, wearing a face mask should be the norm for everyone. This is an extremely important, and inexpensive tool and should be adopted widely – production capacity must be ratcheted up. Face masks should be available for free at all building receptions, offices, etc. We would be foolish not to use a tool that can drastically reduce the risk of transmission of the disease at minimal cost. Needless to say, this implies that the supply shortages of face masks must be solved.

While during official press conferences one hears about tens of millions of face masks being manufactured and more available in FEMA stocks, the reality is quite different – I just sent some face masks to my daughter – an emergency room doctor in the US – whose hospital (a large and well-known institution) is running short. The stories one hears from medical personnel in Canada are similar.

Face mask shortages, as well as those of other personal protective equipment (PPE), are a badge of shame for North American authorities – with two months to prepare, this basic issue was not resolved. One immediate source of face masks is Asia[16], where supplies appear to be plentiful; perhaps a few planeloads per day cannot be brought in until the North American face mask supply chains are working.

- Protect high-risk groups. Seniors homes, rehabilitation centers, social housing catering to elderly population – these are facilities where tough quarantine measures are entirely justified: tightly controlled access, testing all visitors, quick identification and removal of residents displaying symptoms, etc. Prevention of infections in these facilities is crucial to easing the potential burden on the medical system[17]. The same protections must be extended to people with serious pre-existing health conditions (respiratory, etc.).

Some other common-sense measures along these lines:

-

- All elderly and high risk individuals should be identified, advised of the risks they are facing, provided with protective gear (masks, gloves, hand sanitizer), and instructed in its proper use. They should be advised to minimize contacts with others or trips outside their home until the disease abates.

- All families with a live-in elderly of high-risk relative should be similarly instructed.

- Regular monitoring of elderly and high-risk individuals by telemedicine should be adopted.

- Adopt sensible measures to make public places as safe as possible. This is mostly about surface cleaning, minimizing surface contact (tissues, disposable plastic covers, etc.), increasing the frequency of cleaning of public transit, etc. Many of these measures have already been adopted; more could be done.

- Get the economy working again! In the face of rising number of cases, this is politically a very hard decision, but a necessary one. The current policy is likely to lead to a disaster. With the industrial heartland of the US under “stay-in-shelter” orders and most businesses shut down, how long before a wave of business bankruptcies and layoffs becomes a tsunami? How long before financial institutions, that never planned for this sudden and complete economic shutdown, develop problems?

How long before law and order begins to break down in the face of increasing desperation? The current measures were originally set through the end of March. They cannot be allowed to last any longer than that.

-

- We have one to two weeks to solve shortages of face masks, PPEs, test kits and test processing capacity. Nothing should have higher priority than that – the Korean model cannot be put into effect without this.

- Businesses, including hotels, airlines, food service, etc. must be allowed to reopen.

- Day cares, schools, and universities should reopen. There is little one can think of that is more damaging and less useful than closing schools: the children they cater to are not at risk, the parents cannot go to work, etc.

- Mild, economically sustainable social distancing measures can remain. Korean-style apps identifying points where infections were detected and advising people to stay away from these areas until cleaning is complete may be useful. Limiting the number of people in stores at one time, limiting the density of people at sporting events (e.g., only 50% of tickets to sporting events can be sold), closing non-essential and hard-to-disinfect venues like museums – all of these may be continued until the new case counts collapse to South Korean or Chinese levels.

What About the Burden on the Medical System?

Of course, one might wonder: what about the elephant in the room – the increasingly stressed medical system? Will the cancelation of strict social distancing measures not increase the burden to an impossible level? I have three responses to that:

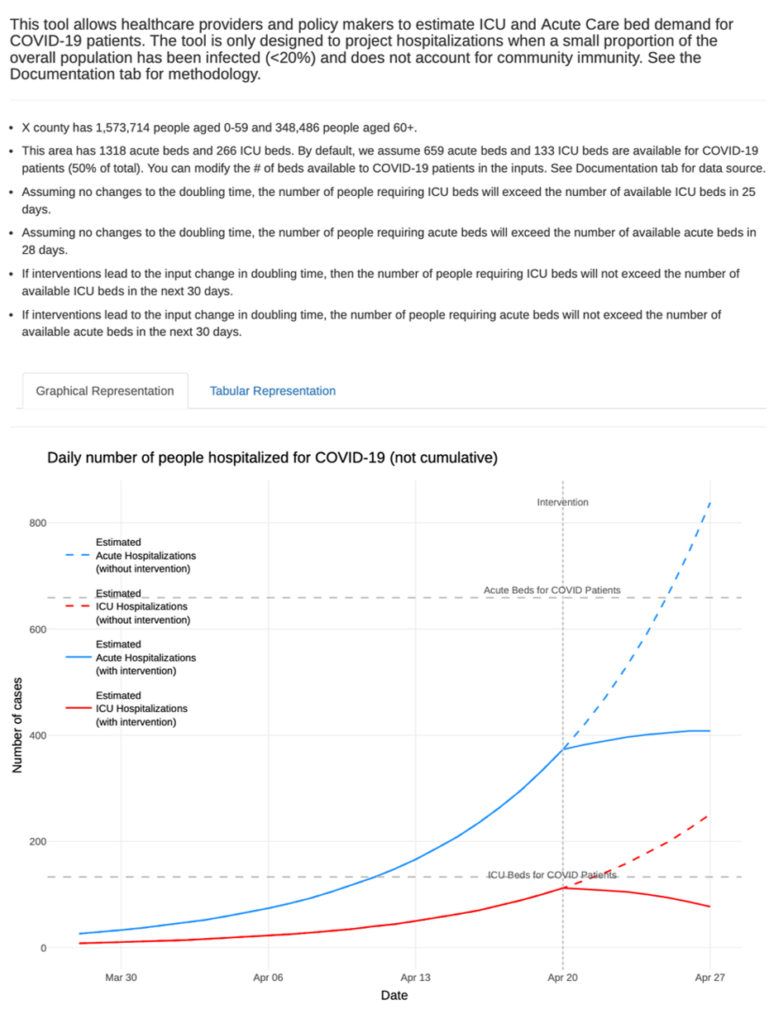

- Increase medical capacity. Targeted actions to increase the capacity of the medical system are essential. Many of these are under way (the use of hospital ships and military stockpiles), more can and should be done. As long as the economic stability of the country is not threatened, these measures are affordable.

- Effective actions will reduce demand. Measures 1-5 described above may achieve as much, or more, to control the number of cases requiring medical interventions as the current “blunt force” approach; this seems to be the lesson from both the Korean and Italian experience. One must remember that the number of newly infected cases detected is not very pertinent to the medical burden: most (80%+, perhaps more if testing is further expanded) of these cases will result in mild or no symptoms, with no required medical treatment beyond basic support during the quarantine. The burden on the medical system will largely be driven by the at-risk population; hence the effective implementation of point 4 is crucial. The introduction of new drugs (already under way, although timing and effectiveness is uncertain) that can reduce the length of stay in the hospital and/or avoid the need for intubation will further reduce the burden.

- The alternative may be worse. If the economic breakdown scenario in point 6 is allowed to develop, the medical system will have many more issues to deal with than the COVID-19 epidemic. Already, gun sales in the US are skyrocketing; population is nervous and breakdowns of law and order are increasingly likely. The faster life is allowed to return to some semblance of normality, the better will the society and the medical system be equipped to focus on the COVID-19 pandemic.

Looking Forward

The “no free lunch” maxim in economics remains valid when applied to our response to COVID-19 pandemic. By adopting strict social distancing measures and shutting down much of the economic activity in the process, we are, whether we admit it or not, trading off potential life years saved by, hopefully, bringing the disease under control faster vs. life years lost due to the sharp rise in unemployment, likely increase in poverty, and the various medical and social ills associated with reduced income. In looking for the right balance between measures that are effective in halting the spread of the infection and are economically sustainable over the long term, we should adopt best practices of countries that were, apparently, able to deal with the pandemic effectively without bringing their economy to a halt. These practices are based on identifying and effectively isolating infected individuals early through massive testing, and adopting low-cost but effective measures like facemasks and other “mild” social distancing measures.

Notes

[1] A good example is the current policy in France is to allow only individual exercise – thus members of the household living together are not allowed to go for a walk.

[2] A recent much-quoted paper from the Imperial College London “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand” https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-NPI-modelling-16-03-2020.pdf is a good case in point. The paper uses a theoretical model that has a great number of parameters, with largely unknown values. The model is “calibrated” to early case trajectory but not the full one. As a result, nearly one-third of the population is projected to be infected eventually (why has this not happened in Wuhan where the total number of cases is less than 1%? Or Japan? Or South Korea?). The dangers of using models with poorly understood data are discussed in detail in the reference in the next footnote.

[3] Ioannidis, J. P.A., “A fiasco in the making? As the coronavirus takes hold, we are making decisions without reliable data”, STAT, March 17. 2020, https://www.statnews.com/2020/03/17/a-fiasco-in-the-making-as-the-coronavirus-pandemic-takes-hold-we-are-making-decisions-without-reliable-data/

[4] A recent guidance from Morgan Stanley projected GDP contraction in the US of 2.4% in Q1 2020, followed by a contraction of 30.1% in Q2, with unemployment rate in Q2 averaging 12.8%.

[5] Not to be confused with the “case fatality rate” – the ratio of deaths to known cases, which is widely reported, but misses the point because testing is heavily skewed towards people displaying serious symptoms.

[6] Lipsitch, M., “We know enough now to act decisively against Covid-19. Social distancing is a good place to start”, STAT, March 18, 2020, https://www.statnews.com/2020/03/18/we-know-enough-now-to-act-decisively-against-covid-19/

[7] This, of course, depends on the length of the shutdown. But if it lasts for months, as many epidemiological models suggest, we may see economic impact on the scale of the Great Depression, i.e., about 25%

[8] A paper “Economic Cost of Flattening the Curve” by Broke-Altenburg and Atherly, March 24, 2020 https://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/economic-cost-of-flattening-the-curve/ reaches similar conclusions, with an important difference – instead of estimating the number of deaths from empirical data as above, the use CDC scenario analysis model that estimates the number of deaths in US between 200,000 and 1.7M, depending on mitigation strategy. These numbers appear totally out of line with the actual number of deaths recorded by China, South Korea, Japan, and other countries where the brunt of the epidemic appears to have passed. Interestingly, even with these hugely inflates number of deaths, the conclusions are similar – the economic case for the current policy is not there.

[9] The fact that face mask stock were depleted retail stores in North America by the end of February, yet one rarely sees them on the street testifies to the effectiveness of the PR campaign – even the ones who bought them were apparently convinced not to use them

[10] This is still the advice e.g. in the public health commercials running in Ontario at this moment

[11] M. Lin, “How to fight the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and its disease,COVID-19”, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZaiDO87me4puBte-8VytcSRtpQ3PVpkK/view?fbclid=IwAR22G45xuIa0n-Dfx0QHFlC-rJSj-H2ZYV_WACSqua06TGQpzqq9-ERBkzU

[12] It appears that instead of building up stocks, the Canadian authorities were depleting them, shipping 16 tons of personal protective equipment to China in February, 2020 https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-ottawa-faces-criticism-for-sending-16-tonnes-of-personal-protective/

[13] “South Korea’s coronavirus response is the opposite of China and Italy – and it’s working”, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/health-environment/article/3075164/south-koreas-coronavirus-response-opposite-china-and

[14]CSSE (JHU) COVID-19 Dataset, retrieved on March 20, 2020. https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19/blob/master/csse_covid_19_data/README.md

[15] The author has heard from front-line doctors in both US and Canada of results taking up to 10 days to come back, rendering the test useless for a disease that can progress from initial symptoms to death in that timespan.

[16] Apparently, China restricts exporting of face masks on a large scale, treating them as a strategic supply. This still leaves countries like Taiwan, Japan and South Korea as potential sources to cover short-term needs. Small-scale shipments can be ordered on a variety of sites, e.g., https://www.alibaba.com/trade/search?fsb=y&IndexArea=product_en&CatId=&SearchText=face+masks+medical+3ply+disposable&isPremium=y

[17] For more discussion along these lines see J. Marshall, “This Should Focus Our Attention on the Vulnerable (News From Italy)”, March 13, 2020 https://talkingpointsmemo.com/edblog/this-should-focus-our-attention-on-the-vulnerable-news-from-italy