Alex F. Mills, PhD, Zicklin School of Business, Baruch College, and Jonathan E. Helm, PhD, Kelley School of Business, Indiana University

Abstract

Contact: Alex.Mills@baruch.cuny.edu

What is the message?

Three steps that hospitals can take today to prepare for COVID-19 or any similar pandemic are (i) limit predictable variability by cancelling or smoothing elective surgeries in advance of an epidemic’s impact rather than waiting until inpatient units are overwhelmed, (ii) centralize staffing, resource-planning, and allocation decisions, while employing healthcare coalitions to quantify and locate scarce resources like ICU beds and ventilators, and (iii) prepare a plan for triage guided by the principle “do the greatest good for the greatest number”.

What is the evidence?

The observations are based on recent research in healthcare operations management, as well as the authors’ own discussions with healthcare providers.

Timeline: Submitted: March 13, 2020; accepted after revisions: March 14, 2020

Cite as: Alex F. Mills and Jonathan E. Helm. 2020. Medical Surge: Lessons for a Pandemic from Mass-Casualty Management. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (HMPI.org), volume 5, Issue 1, special issue on COVID-19, March 2020.

What is “Medical Surge” and Why Does It Matter?

Medical surge is the ability to rapidly increase the supply of medical services in a community to care for a volume of patients that is larger than normal. Medical surge is one of four core capabilities in the Hospital Preparedness Program1. We draw lessons from the operational literature in surge capacity, mass-casualty management, and healthcare operations management that can be applied to improve medical surge in the context of a pandemic.

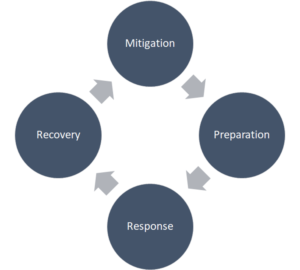

Much research on operational measures to create surge capacity has been done with mass-casualty incidents in mind. Both mass-casualty incidents and epidemics pose challenges to the healthcare system that are primarily operational rather than clinical. Healthcare providers usually know what kind of care the patients need, but lack the resources to provide it. Many of the lessons from mass-casualty management can also improve the management of an epidemic in the context of the four-phase emergency response framework consisting of mitigation, preparation, response, and recovery (see Figure 1)2.

In this article, we use these lessons to outline specific operational steps hospitals can take at three points to respond to an epidemic: in the mitigation phase before resources are severely limited; from the preparation phase into the response phase when resources become severely limited; deep in the response phase when resources are completely overwhelmed.

Figure 1

Mitigation Phase: Shift Gears

Before resources are severely limited: Minimize controllable volume and variability in hospital workload by limiting or smoothing elective surgeries and planned admissions in preparation for epidemic response.

Efforts to improve medical surge capacity often focus on increasing supply by calling in additional personnel, using physical space not generally designated for patient care, and modifying standards of care3. The demand side of the equation deserves equal attention, especially in the time period before resources are completely overwhelmed, which is when actions to control demand have the most impact. To limit demand, researchers have proposed two types of actions: (1) early disposition of existing patients, and (2) controlling new demand. Because pandemics have a gradual onset as compared to mass-casualty incidents, procedures for early disposition of existing patients (point 2) 4,5 are less relevant, while actions to control new arrivals (point 2) take on greater importance.

Elective surgeries and other planned admissions have two impacts on hospital operations: volume and variability. The presence of elective surgeries increases the overall volume of patients in the hospital, which affects the number of available inpatient beds, but the additional variability induced by these arrivals is more pernicious because it has a cascading effect throughout the hospital.

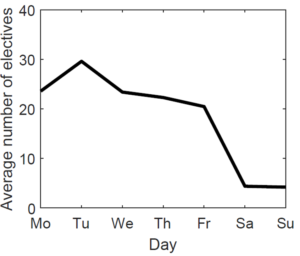

Elective surgeries are scheduled based on the convenience of the patient and provider, not the hospital (see Figure 2, which shows the arrival pattern for elective surgeries at one hospital the authors have worked with). As a result, these planned arrivals are concentrated together, artificially creating resource scarcity at key times of day and days of the week6. The effect of this predictable variability can be felt not just in inpatient units where these patients are hospitalized, but also in the Emergency Department, where lack of inpatient beds at key times worsens boarding and redirects resources away from arriving patients. Smoothing arrivals by spreading out elective surgeries reduces costly actions such as early disposition and increases surge capacity7.

Figure 2

Canceling or postponing elective surgeries and planned admissions in advance of an epidemic, before resources are severely limited, will delay the impact of the epidemic on a hospital’s operations. Equally important, for planned admissions that cannot be deferred, smoothing workload reduces the impact of these predictable arrivals on resources that are needed for epidemic response. Smoothing reduces large swings in hospital occupancy that cause the hospital to be overloaded at certain times and underloaded at others. Because overloading is the greatest concern in an epidemic, mitigating actions can substantially improve responsiveness, access, and quality of care for affected individuals. Much of the benefit from workload smoothing can be obtained by reshuffling surgery schedules across weekdays, for example moving some surgeries from Tuesday to Friday, though complete workload smoothing may require some electives to be performed on weekends or overnight to minimize the strain on the hospital’s resources that are needed to respond to the epidemic.

Preparation Phase: Getting Ready to Respond

When resources are severely limited: Centralize and coordinate decision-making on physical resources and staff.

As an incident evolves and demand increases, responsibility shifts from individual hospitals to hospital networks and the community. In this mode of operation, centralizing information and decision-making becomes the most important operational step that healthcare providers and communities can take, because any single hospital is ill-equipped to deal with a large-scale pandemic. Specifically, centralization enables healthcare organizations and communities to most effectively deploy their full set of care resources, avoiding misallocation caused by variability in geography and volume caused by disease spread through resource pooling. Effective incident response requires two critical resources: physical and human. Here, we highlight several innovative operational mechanisms that can facilitate pooling and optimal deployment of both types of resources.

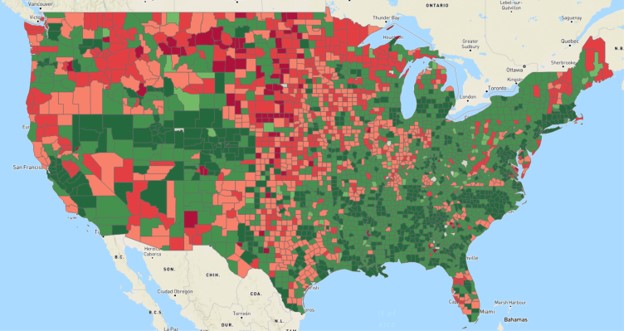

Physical resource management: Understanding the location and capabilities of each available physical resource within a community is the responsibility of healthcare coalitions. A healthcare coalition is a “group of individual healthcare organizations in a specified geographic area that agree to work together to maximize surge capacity and capability during medical and public health emergencies by facilitating information sharing, mutual aid, and response coordination”8. As part of our research, the authors have worked with MESH, a healthcare coalition in Indianapolis, IN that facilitates information gathering and sharing among dozens of healthcare providers in central Indiana. A key role of healthcare coalitions is to support community response by enabling sick patients to be taken to facilities that will be most likely to be able to care for them. In the absence of structured information sharing via healthcare coalitions, hospitals tend to be reluctant to share detailed capacity information, citing concerns about competition9.

While emergency medical services typically have some visibility into available capacity of Emergency Departments, we demonstrated that more granular information provided by a healthcare coalition regarding the availability of beds in specific units (such as the ICU) can substantially improve the response to a mass-casualty incident9. A similar lesson can be applied to an epidemic.

For example, COVID-19 causes severe respiratory symptoms that often require ventilation and intensive care10. In responding to an epidemic of COVID-19, the geographical distribution of ventilators and ICU beds in a community likely will not match the geographical distribution of patients or the capacities of Emergency Departments. For example, using data only about Emergency Department capacity may direct a patient away from a hospital with a highly utilized ED, even though that hospital may have available ventilators or ICU beds, necessitating an unnecessary transfer later.

Sharing information on specific physical resources and providing centralized coordination will maximize the utilization of the community’s combined healthcare resources. This can reduce delay for patients in accessing care and maximize the number of patients that can be effectively treated during the pandemic.

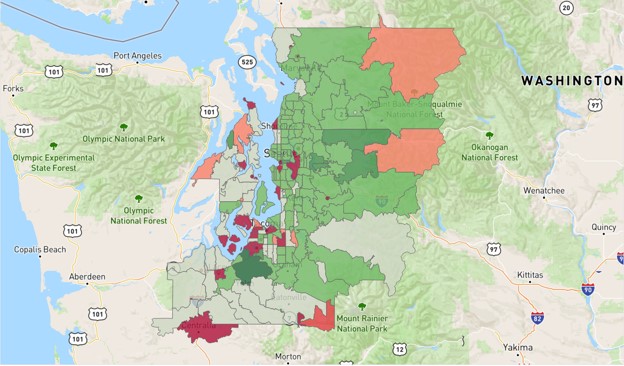

Human resource management: Beyond the physical resources required to support treatment of patients, medical surge capacity also suffers if there is inadequate number of staff, such as nurses. Recent research in healthcare operations management has studied the trend toward centralized staffing in larger healthcare systems such as the Cleveland Clinic, Indiana University Health System, Kaiser Permanente, Denver Health, Seattle Children’s Hospital, and Intermountain Healthcare. The move to centralized staffing can significantly improve response to an epidemic by addressing geographic variability in healthcare staff.

A centralized staffing approach allows a health system to re-allocate nurses from their resource pool to areas with the greatest need, helping to maintain safe nurse to patient ratios. This system-wide approach mitigates common problems that lead to understaffing in certain hospitals, while other hospitals have sufficient or excess capacity. Along with centralized staffing comes centralized data-systems to enable a data driven approach using analytics models to predict staffing needs across the system and allocate resources most effectively11.

Centralized staffing also enables data-driven, proactive hiring of temporary nurse staff. With an accurate disease models, such as the SEIR model recently developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for COVID-1912, it is possible to predict demand on a regional basis across time. A centralized staffing approach can facilitate the hiring of temporary nursing resources such as agency nurses and travel nurses13.

Because it can take between several weeks and two months to onboard temporary nurse staff, predictive models and data-analytics must be used to enable a proactive approach to best match supply and demand to the evolving dynamics of an epidemic. Leveraging a centralized data system can help health systems coordinate hiring and allocation of nurse staff to best match supply and demand across the network of hospitals, and the flexibility of centralized scheduling can most efficiently use the additional nurse staff to provide agility for healthcare organizations to quickly react to dynamic fluctuations in workload caused by disease spread.

Centralizing information and decision-making about physical capacity and staff is a critical operational step that providers must take to effectively prepare for and respond to an epidemic. Both healthcare coalitions, which coordinate a community’s healthcare assets, and hospital systems, which have the ability to centralize staffing decisions, play a key operational role.

Response Phase: Making it Work for as Many as Possible

When resources are completely overwhelmed: do the greatest good for the greatest number.

At some point in an epidemic, healthcare resources may become completely overwhelmed. In this situation, it is especially important to have a plan for allocating the available medical resources. Here, mass-casualty management provides a clear lesson: providers must shift focus from doing the greatest good for each patient to doing the greatest good for the greatest number14.

Consistent with this principle, a number of triage systems have been proposed for mass-casualty management15. All have one thing in common: they do not use scarce resources to treat patients who have little chance of survival, unlike in normal hospital operations, where the most severe patients always have the highest priority for treatment.

Recent mathematical modeling research has reinforced this idea and added additional context to our understanding of how to prioritize patients to maximize the total number of survivors16–18. When a resource limitation is expected to last a short period of time, priority should be given to patients who are deteriorating most rapidly; but when the resource limitation is expected to last a long time, priority should be given patients who have a high likelihood of survival if treated19. Because pandemics tend to last for a long period of time, in preparing for a pandemic the principle of “do the greatest good for the greatest number” translates into a policy of prioritizing patients who are most likely to survive in the event that resources become completely overwhelmed.

Looking Forward

Epidemics and mass-casualty incidents share a common feature. They pose an operational challenge to the healthcare system and require medical surge, an increase in the supply of healthcare services to meet increased demand.

Based on the lessons from research in healthcare operations management, we propose three steps that hospitals can take today to prepare for COVID-19 or any similar pandemic: (1) limit predictable variability by cancelling or smoothing elective surgeries in advance of an epidemic’s impact rather than waiting until inpatient units are overwhelmed, (2) centralize staffing and resource-planning and allocation decisions and employ healthcare coalitions to quantify and locate scarce resources like ICU beds and ventilators, and (3) prepare a plan for triage guided by the principle “do the greatest good for the greatest number”.

References

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. 2017-2022 Health Care Preparedness and Response Capabilities. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Emergency preparedness standards for medicare and medicaid participating providers and suppliers. 2013;78(FR):79081.

- Hick JL, Hanfling D, Burstein JL, et al. Health care facility and community strategies for patient care surge capacity. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2004;44(3):253-261.

- Kelen GD, Kraus CK, McCarthy ML, et al. Inpatient disposition classification for the creation of hospital surge capacity: a multiphase study. Lancet. 2006;368(9951):1984-1990.

- Jacobs-Wingo JL, Cook HA, Lang WH. Rapid Patient Discharge Contribution to Bed Surge Capacity During a Mass Casualty Incident: Findings From an Exercise With New York City Hospitals. Quality Management in Health Care. 2018;27(1):24-29.

- Rothman RE, Hsu EB, Kahn CA, Kelen GD. Research priorities for surge capacity. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2006;13(11):1160-1168.

- Mills A, Helm J, Wang Y. Surge Capacity Deployment in Hospitals: Effectiveness of Response and Mitigation Strategies. Manufacturing and Service Operations Management, forthcoming. 2020. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2955766

- Barbera JA, Macintyre AG. Medical Surge Capacity and Capability: A Management System for Integrating Medical and Health Resources during Large-Scale Emergencies. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2007.

- Mills AF, Helm JE, Jola-Sanchez AF, Tatikonda MV, Courtney BA. Coordination of autonomous healthcare entities: Emergency response to multiple casualty incidents. Production and Operations Management. 2018;27(1):184–205.

- Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2020.

- Wright PD, Mahar S. Centralized nurse scheduling to simultaneously improve schedule cost and nurse satisfaction. Omega. 2013;41(6):1042–1052.

- Pan J, Yao Y, Liu Z, et al. Effectiveness of control strategies for Coronavirus Disease 2019: a SEIR dynamic modeling study. medRxiv. 2020.

- Seo S, Spetz J. Demand for temporary agency nurses and nursing shortages. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2013;50(3):216–228.

- Frykberg ER. Disaster and Mass Casualty Management. Springer; 2007.

- Lerner EB, Schwartz RB, Coule PL, et al. Mass casualty triage: An evaluation of the data and development of a proposed national guideline. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2008;2(Supplement 1):S25-34.

- Sacco WJ, Navin DM, Fiedler KE, Waddell RK, Long WB, Jr RFB. Precise formulation and evidence-based application of resource-constrained triage. Academic Emergency Medicines. 2005;12(8):759-770.

- Mills A, Argon N, Ziya S. Resource-based patient prioritization in mass-casualty incidents. Manufacturing and Service Operations Management. 2013;15(3):361-377.

- Dean MD, Nair SK. Mass-casualty triage: Distribution of victims to multiple hospitals using the SAVE model. European Journal of Operational Research. 2014;238:363-373.

- Mills A. A simple yet effective decision support policy for mass-casualty triage. European Journal of Operational Research. 2016;253:734-745.