Brooke Istvan, Graduate School of Business; Perry Nielsen Jr,; Megan Eluhu, School of Medicine, Bryan Kozin, Walt Winslow, Graduate School of Business, David Scheinker, Kavita Patel, School of Medicine, Kenneth Favaro, Stefanos Zenios, Graduate School of Business, and Kevin Schulman, Graduate School of Business, Hospital Medicine and Clinical Excellence Research Center, School of Medicine; Stanford University

Professors Zenios and Schulman are co-senior authors.

Contact: kevin.schulman@stanford.edu

Abstract

What is the message?

Precedents Thinking — applying past solutions to solve similar problems in a different industry setting — can be applied to what has been the intractable challenge of reducing $265 billion in annual administrative waste in U.S. healthcare. The Precedents Thinking methodology: 1) frames the problem statement and its key elements, 2) searches for prior innovations, “precedents”, that are relevant to one or more of the problem’s key elements, and 3) combines the precedents into the best possible workable solution to the problem. As a result of their findings, the authors propose standardized, modularized digital contracts and the construction of a uniform digital transaction platform.

What is the evidence?

The authors identified 82 firms or markets that have successfully addressed challenges of this magnitude, focused on a subset of 26 innovations, and developed a proposal for contract standardization and payment infrastructure development that could address transaction costs in healthcare.

Timeline: Submitted: November 4, 2024; accepted after review November 19, 2024.

Cite as: Brooke Istvan, Perry Nielsen Jr, Megan Eluhu, Bryan Kozin, Walt Winslow, David Scheinker, Kavita Patel, Kenneth Favaro, Stefanos Zenios, Kevin Schulman. 2024. Applying Precedents Thinking to the Intractable Problem of Transaction Costs in Healthcare. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.HMPI.org). Volume 9, Issue 3.

Introduction

Administrative costs represent a considerable burden in the U.S. healthcare market.1,2,3,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Administrative costs account for nearly one quarter of the $4.8 trillion spent on healthcare services.14 Among OECD countries, the United States spends nearly ten times the average on healthcare administrative functions per capita.15 Estimates suggest that we can readily eliminate at least $265 billion annually in spending from reducing this administrative burden.1,2

While the burden of administrative costs in the U.S. healthcare system has been well recognized, developing solutions to this challenge has proved vexing. Efforts to understand why these administrative costs are so high highlight the complexity of the market (317,987 different health plans, 599,204 codes for products or services, and 57 billion negotiated prices12). Other efforts have described the high billing and insurance-related costs resulting from the architectural complexity of the contracting process, the complexity of the health plan contracts with providers, and compliance costs.13 Moreover, much of the administrative effort in healthcare is based on digitized analog processes, with requirements for phone calls, faxes, and transmission of paper (or PDF) documents. Other challenges include the lack of a regulatory body overseeing the market. The academic and policy literature assessing the problem of healthcare administrative costs suggests little opportunity to change given the lack of a catalyst for improvement, no market forces demanding change, and no oversight mechanisms holding the market accountable for improving this situation.

However, an alternative perspective is to consider that this is not an intractable problem. There are many markets which have faced daunting challenges such as we have described for the healthcare market and have seen significant change.

How firms and markets change is an exciting area of research in the business literature. The challenge is to ascertain an underlying strategy for reproducible and predictable innovation processes. If such an approach can be articulated, it would offer a new way to address seemingly intractable issues such as the administrative cost issue in the U.S. healthcare market.

Precedents Thinking is one of the newest advances in this field of research.4 It builds from the observation that all innovative solutions are creative combinations of prior innovations, “precedents”, found in different businesses and markets that faced similar challenges. If we can find the best precedents, then we can increase our chances of developing an innovative, workable solution to the problem at hand. One barrier to large-scale innovation, or addressing intractable problems, is that it is hard to generate the investment required (money, time and effort, or policy interest in a crowded legislative/regulatory space) to tackle daunting issues such as administrative costs at the required scale. The Precedents Thinking methodology offers innovators a set of proven solutions across firms and markets. One theory is that by limiting innovation to proven solutions, we may have de-risked the problem sufficiently to attract investment required to tackle the problem.

In this paper, we apply Precedents Thinking to the problem of administrative costs in U.S. healthcare.

Methods

Precedents Thinking is a method where past solutions to similar problems are used in new situations to come up with innovative ideas. We applied the Precedents Thinking methodology to the issue of U.S. healthcare administrative spending. Precedents Thinking methodology has three distinct steps: 1) framing the problem statement and its key elements, 2) searching for prior innovations, “precedents”, that are relevant to one or more of the problem’s key elements, and 3) combining the precedents into the best possible workable solution to the problem.

1. Problem Statement and Deconstructions

The problem statement and deconstructions identify the core elements of the problem to highlight generalized features that could be used in the precedents search process. The problem statement and its key elements known as “deconstructions”, were developed through a workshop using a modified Delphi consensus process featuring expert facilitation. Participants were research team members and selected outside advisors, including the two developers of the Precedents Thinking methodology (see appendix exhibit a1). Participants were provided prereading materials that included explanations and examples of the Precedents Thinking methodology.

The group divided into two breakout sessions. Each breakout group was charged with narrowing the problem statement and defining its elements, the “deconstructions”. The workshop resumed as a whole to refine the two problem statements and deconstructions of each group into a workshop consensus statement and deconstructions. The problem statement and deconstructions continued to be refined over the course of the effort, but, for readability, only the final version is reported in the results section below.

2. Precedent Generation and Selection

Based on the workshop consensus problem statement and deconstructions, the research team began a search for precedents. The goal of this step was to develop an exhaustive list of firms or markets that had successfully implemented solutions to the problem statement within and outside of the healthcare market. Precedents were included if they were: 1) highly relevant to at least one problem deconstruction, 2) had strong evidence of success beyond luck, and 3) were more detailed than a common best practice. The precedent generation process included brainstorming among workshop participants, interviews with a broader group of industry experts and steering committee members, and a final step of using ChatGPT with a prompt of the problem statement alone and with each of its deconstructions until the output was hallucinatory or nonsensical.16

Each precedent was systematically described with background, insights, and outcomes.

Precedents were classified by industry, governance (public, private, public-private) and primary mode of change (digitization, centralization, standardization).

An initial item reduction step was taken by the research team to arrive at a shorter list of priority precedents based on impact, feasibility, trust building capacity, and applicability to the problem statement. Impact was assessed via capacity to simplify the system and reduce complexity of processes; feasibility was assessed by governance structure (i.e., private, public-private, public) and primary mode of change (centralization, standardization, digitization). Building trust across stakeholders was a binary categorization that held the same weight as the other categorizations. To determine applicability to the problem statement, we used a graphical approach to item summarization where precedent summaries were applied to the problem statement and deconstructions in 2×2 matrixes where each dimension was the level to which the precedent solved each deconstruction. The precedents were then ranked by impact, feasibility, and trust and selected to include a variety of industries and unique insights around the theory of change. A subset of 26 high-priority precedents emerged.

The 26 high-priority precedents were summarized into written briefs including background, key insights, business model, ownership, and impact on heterogeneity, complexity, trust, cost, user experience, productivity, and profitability.

3. Creative Combinations

The final step was to refine the precedents into an actionable set of solutions from the 26 high-priority precedents. This step allowed for the aggregation of precedents into composite solutions applicable to the healthcare market.

Each working group member was assigned to create at least two creative combinations of two to three precedents that solve the problem statement through at least one of its deconstructions. The full team then met and summarized the individual responses into a final summary consensus solution for the healthcare market. The group reviewed the creative combinations generated by each participant and used breakout groups to further refine the individual assignments into consensus sets of precedents and creative combinations to address the problem statement and deconstructions. The breakout groups’ solutions were then compared against each other and combined into a final set of precedents and creative combinations for each deconstruction of the problem statement.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize the precedents developed from the precedent generation step of this effort.

Results

Problem Statement and Deconstructions

The final problem statement defined by the workshop was: How to create the standardization and infrastructure that’s needed to reduce administrative waste in healthcare? We developed two deconstructions of this problem statement:

Deconstruction 1: How to reduce heterogeneity and complexity of contracts that results in administrative burden

Deconstruction 2: How to create the necessary payment infrastructure to support an efficient healthcare transaction ecosystem

Precedent Generation and Selection

We were able to generate 82 precedents for this stage of the research (see Appendix Exhibit a2). A majority (72%) were drawn from Finance, Healthcare, Public Services, & Technology. In terms of governance, 57% of our precedents were private sector solutions, 22% were public sector solutions, and 21% were developed through public-private partnerships. Regarding mode of change, 49% used standardization as a primary mode of change, 29% used digitization, and 22% used centralization. Finally, 35% of precedents were thought to have improved trust in the market. Descriptive data for all precedents and a subset of 26 high priority precedents are reported in Exhibit 1.

| Exhibit 1: Summary characteristics of precedents |

| Industry |

Full precedent list

(N=82) |

High priority precedent list (N=26) |

| Consumer Products |

2 |

(2%) |

2 |

(8%) |

| E-Commerce |

7 |

(9%) |

3 |

(12%) |

| Entertainment |

4 |

(5%) |

1 |

(4%) |

| Finance |

18 |

(22%) |

8 |

(31%) |

| Food Services |

3 |

(4%) |

1 |

(4%) |

| Healthcare |

10 |

(12%) |

2 |

(8%) |

| Logistics |

5 |

(6%) |

1 |

(4%) |

| Public Services |

18 |

(22%) |

3 |

(12%) |

| Real Estate |

2 |

(2%) |

0 |

(0%) |

| Technology |

13 |

(16%) |

5 |

(19%) |

| Ownership |

|

|

|

|

| Private |

47 |

(57%) |

17 |

(65%) |

| Public |

18 |

(22%) |

3 |

(12%) |

| Public-Private |

17 |

(21%) |

6 |

(23%) |

| Primary form of change |

|

|

|

|

| Centralization |

18 |

(22%) |

10 |

(38%) |

| Digitization |

24 |

(29%) |

5 |

(19%) |

| Standardization |

40 |

(49%) |

11 |

(42%) |

| Trust |

|

|

|

|

| Improved Trust |

29 |

(35%) |

14 |

(54%) |

| Not Impacting Trust |

53 |

(65%) |

12 |

(46%) |

Legend: Full precedent list is the result of the precedent generation exercise. High priority precedent list is the final list of precedents used in the creative combination exercise.

Creative Combinations

The final creative combinations aimed to solve both problem statement deconstructions (contract standardization and payment infrastructure) by applying the learnings from a consensus set of our precedents narrowed in on by our working team. The precedents that informed our core solution were:

- Modularized machine-readable contracts:

- Standardized mortgages

- Mobile phone standard setting organizations (SSOs)

- Payment Infrastructure:

- Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT)

- Stripe

- SMART on FHIR

- State utility commissions

- FAA

See Exhibit 2 in the Appendix for the complete summary of relevant precedents.

Solution Part 1: Modularized machine-readable contracts

Part one of the solution aims to implement modularized machine-readable contracts in a digital and unified manner. In the current market, each payer (or individual health plan) must negotiate a contract for services with each in-network provider organization. While features of these agreements refer to a similar set of business processes, they do not follow any standardized structure or standard set of fully digital processes.12 Further, novel features such as value-based payment models are further individualized for payers or plans (often resulting in entirely analog transactions).

Building from our learnings on mortgage standardization, we propose a single, modularized digital contract format. In the early 1970s, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac standardized to a modular format to improve the mortgage process and to allow syndication of these now standard mortgage products.3 Our working definition of a modularized machine-readable contract is one that is designed to be digitally adjudicated. Such a contract will have a standard structure and set of contract terms terms (See illustrative example in Exhibit 3). For example, items that are typically addressed in these agreements include billing processes, payment terms, additional requirements such as prior authorization processes, quality reporting, confidentiality, and regulatory compliance. We have defined these agreements as modularized, not uniform. In other words, agreements could be customizable by health plans under this structure, but customization could not alter the requirement for complete digital adjudication.

Exhibit 3: Modularized Machine-Readable Contracts

Legend: Each insurer could design new contracts, or reproduce the logic, requirements, and processes of each of their current contracts, with the Modularized Machine-Readable Contracts framework. Each care provider could use a single operational and technical framework to interact with every contract from every insurer. Differences between contracts would be captured with standardized categories of inputs and outputs, variables, and functions. To resolve edge cases not captured in the contractual logic, insurers and providers could continue to work as in the current state.

Single Sign-Ons (SSOs) are industry or public-private partnerships that bring together competing firms that collectively select and adopt uniform technical standards to ensure compatibility and interoperability among products. This approach has allowed for standardization and innovation that supports the enormous mobile phone market. The SSO process could be used to determine the final content of the modularized machine-readable contracts, as well as technical supporting details (such as a requirement for SMART on Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) APIs for digital transactions). The SSO for such a process could build from industry (America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), for example) or could be constructed through the Federal government (the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or the Department of Commerce, for example).

The process of selecting a modularized and machine-readable contract structure would drive innovation in contract design and build engagement from across the industry. In the mobile phone SSO process, each industry partner submits their proposal for mobile phone standards. The best option available is selected by the SSO body and becomes the standard for the industry (for a fixed time, this is an ongoing innovation process). Firms are incentivized to contribute their intellectual property (in the mobile phone market this in in the form of patents) because when one firm’s technology is selected, their relevant patents are deemed standard-essential patents (“SEPs”), generating royalty payments from the other firms in the market. Since contract elements may not be patentable, the SSO process may have to develop other compensation schemes to support collective engagement with the process.

Solution Part 2: Uniform Payment Infrastructure

Standardized contracts would enable the construction of a uniform digital transaction platform for the U.S. healthcare market. Such a platform should be seen as critical core infrastructure supporting the market. Currently, each health plan utilizes their own platform to process healthcare claims or relies on a limited set of “clearinghouses” in the market. Given the heterogeneity in transaction processes in the current healthcare market, there is significant underinvestment in this infrastructure (an issue that was highlighted by the recent cyberattack on Change Healthcare14).

Stripe has built a comprehensive, digital-first backend payment infrastructure that has created a trusted and centralized payment process for vendors across industries with easy access through APIs. Given a standard contract, it is easy to envision the development of a consistent payment processing infrastructure for all payers and providers to use, eliminating the payment inconsistencies that exist in the market today. This infrastructure would house (and implement) the digital contracts to ensure the integrity of the payment process.

SWIFT is a consortium of financial institutions that developed a digital communication system that underlies most banking transactions. The SWIFT network demonstrates that a digital transaction platform can be reliable, secure and robust, even at enormous scale. It is also an example of such a platform emerging out of collective industry action that later expanded to include the Federal Reserve and other central banks as opposed to one created through regulation.

Financing critical infrastructure such as this transaction platform usually follows a pattern of initial investment followed by a self-sustaining financial model (say, by collecting a transaction fee for each payment). In this case, the required transaction fees are likely to be substantially lower than the cost per payment transaction under the current model. Currently, there are no governance mechanisms in the market to support the development of this infrastructure. While the private sector could deploy the capital required for this effort, a purely private transaction platform could be subject to rent-seeking by the platform owner over time, limiting the economic benefits of this initiative. Creating a public or a public benefit corporation to develop and oversee this platform could be a pathway to addressing this challenge. Creating a public oversight mechanism would help to ensure transparency and accountability across the market and possibly avoid rent-seeking. For example, another precedent is how the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) centralized the infrastructure and agencies needed to support commercial aviation in the U.S. and how state utility commissions regulate public utilities and their profits.

Discussion

The high administrative cost burden of U.S. healthcare is a seemingly intractable problem. These costs result from tremendous complexity in transactions across the diversity of health plans, and the lack of oversight and attention to this issue at the federal and state levels. This is not just an abstract concern about the market. Complexity and administrative challenges are a burden to patients and cost consumers an enormous amount of time by having to negotiate insurance terms and conditions, prior authorization, and appeals processes. These challenges interrupt patients’ access to care, resulting in delayed diagnoses and treatment. 18,19

The Precedent Thinking methodology described in the business literature suggests one model for developing predictable and scalable innovation. This model requires the identification of a key problem statement, developing and refining a set of firms and markets which have successfully addressed a business challenge similar to the core problem, and then adapting these precedents to a solution for the market of interest.20,21 We challenged ourselves to understand how to standardize transactions and create an infrastructure that would be needed to reduce administrative waste in healthcare. We identified 82 firms or markets that have successfully addressed challenges of this magnitude, focused on a subset of 26 of these innovations, and developed a proposal for contract standardization and payment infrastructure development that could address transaction costs in healthcare.

The Precedent Thinking methodology helped us to understand how other firms and industries have successfully addressed challenges of the magnitude faced in the healthcare market. In developing the idea for modularized machine-readable contracts, we identified home mortgages and mobile phone standard setting organizations as key precedents. In developing the idea for a digital transaction infrastructure, we have identified the work of the firm Stripe in financial markets, the SWIFT infrastructure for the banking system, the APIs available through SMART on FHIR, the role of the FAA in the aviation market, and state public utilities commissions. These precedents provide critical insights for solving the administrative cost challenge of the U.S. healthcare market.

In a focused exploration of business precedents, we found that other industries have solved large, seemingly intractable problems like an analog to digital transition. From this effort, we discovered that standardization and digitization have been successfully deployed in several markets, generating key insights that can be applied to the U.S. healthcare market. We identified that large-scale market change does not require initial government initiative (private initiatives have been successful), though government involvement can drive adoption across stakeholder groups.

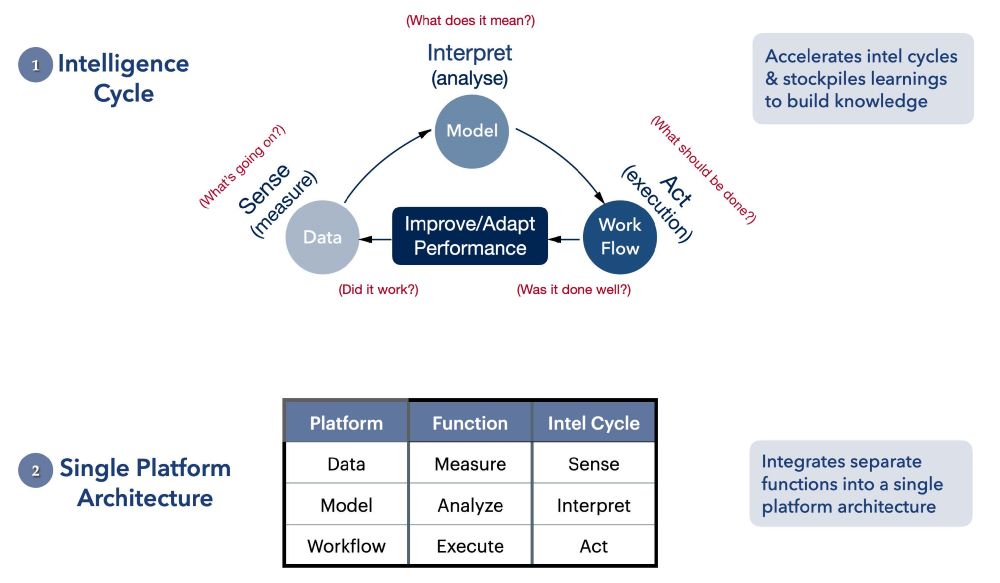

Another important insight from Precedents Thinking is how solutions such as standardization and digitalization can create positive network effects in a market. Developing modularized, machine-readable contracts and, correspondingly, standardizing a transaction platform, can lead to transaction efficiency, market entry, enhanced liquidity, competition, and value in a manner that can continue to build over time through investments in improved infrastructure and transaction processes (Exhibit 4). For example, it could enable the securitization of insurance contracts to enhance liquidity in the market.

Exhibit 4: Catalyzing a Virtuous Cycle in Healthcare

Legend: Adoption of modularized machine-readable contracts and the unified digital payment infrastructure would enable a virtuous cycle of follow-on impacts across the healthcare market over time. The platform would lower transaction costs thanks to standardized and centralized digital payments. Reducing transaction costs and “friction” associated with the payment infrastructure would ease entry of new firms and products into the market. These new entrants would drive increased competition and investment that would improve the value of the healthcare provided by the system. Clear improvements to value would generate increased investment in the digital payment infrastructure that would allow the virtuous cycle to continue.

Our work is not the only effort to understand the high administrative costs in healthcare. Several authors have identified the high administrative costs in the U.S. healthcare system1,2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 and some have proposed ideas to help reduce waste.2,3,6,9,10,22,23,24,25,26,27 Their work validates the enormous waste in the market and focuses on an overlapping set of potential solutions that can be deployed to address these challenges. However, the path to achieving such solutions remains unclear. Precedents Thinking has allowed us to think deeper about how truly transformative solutions at scale could be implemented.

One result from this work is a better understanding of the critical role of standardization and infrastructure investment in addressing the high transaction costs in healthcare. Many of the precedents studied that have successfully addressed these challenges come from the finance industry where government structures such as the Federal Reserve Bank have helped to establish, catalyze, coordinate, and regulate different aspects of the financial markets. Obviously, we lack such a coordinating entity in the U.S. healthcare market. Using our formulation of a solution, it would be possible to examine how existing legislative authority can be used to implement our solution, including legislative authority under HIPAA, the Affordable Care Act, and through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Additionally, broad executive actions around AI could be leveraged to develop a contractual and payment infrastructure environment for safe AI use. An alternative governance structure could include the role of agencies such as the U.S. Labor Department (through the employer health plan fiduciary obligations) or the Commerce Department. New legislative authority might be required to fully implement the complete set of precedents we have identified in the healthcare market. For example, federal legislation could establish a centralized authority overseeing healthcare payment transactions similar to the federal reserve and state legislation could mandate use of a standard transaction platform by physicians and hospitals licensed within a state when engaging with health plans.

States could also play a key role in addressing high administrative costs because of smaller scale and faster implementation times. Programs like Medicaid, managed at the state level with federal funding, could provide a means of scaling successful standardization efforts.

One challenge for the governance structure is the inherent conflict between standardization and heterogeneity in the market. While it is possible to build technology that can implement enormous complexity in an algorithmically-driven payment process model, the more we enable complexity, the more we risk diluting some of the economic benefit of standardization. Health plans have built their marketing efforts on facilitating health plan customization, even with little economic support for this approach (for example, the Medigap market has 10 health plan structures,28 while the individual insurance (Obamacare) exchange plans have the same benefit structures but differ in cost-sharing provisions29). At the extreme, it’s easy to postulate that there is little economic or market rationale to support the current 317,987 different health plan structures in the new infrastructure, but the degree to which plan customization is a required design element should be a matter of further discussion.

Even with substantial government involvement, industry participation is a prerequisite for the successful adoption of modularized contracts and a digital infrastructure. One possibility is that SSOs provide a platform through which industry partners agree to details such as the degree of plan customization. SSOs could also play a role in making final decisions about digital infrastructure across the industry. Besides SSOs, private entities could collaborate with government on policy options through working committees and nonprofit coalitions. Beyond the initial adoption of new contracts and infrastructure, industry partners could also provide critical insights to guide change management and improvements over time. Incumbent industry leaders unsettled by the potential for a new transaction model that disrupts their core business model might need to be pulled into this effort by government or customers.

Limitations

The strength of the Precedents Thinking method is the robustness of the three steps in the process. While we convened an outstanding research team and steering committee, other efforts to apply the same methodology to this problem could have identified a different set of solutions. Further, while we tried to be exhaustive in developing precedents for discussion, we could have missed key innovations in other markets in the U.S. and globally. Finally, our assumption behind the Precedents Thinking approach is that the solutions can generalize to the healthcare market and scale, and both assumptions are untested.

Conclusion

We applied Precedents Thinking methodology to the challenge of high administrative costs in the U.S. healthcare market. Using business precedents from markets and firms inside and outside of healthcare, we identified contract modularization and the development of a digital payment infrastructure as a solution than can address this challenge at scale. There are remaining questions about the governance model for implementing these solutions and the potential to pilot and scale, but overall, we conclude that high administrative costs need not be an intractable feature of the U.S. healthcare market.

Acknowledgements:

Funding provided by The Ludy Family Foundation, the Hirsch Family Foundation, Gates Ventures, and the Government, Business and Society Initiative at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Appendix

Exhibit 2: Summary of Relevant Precedents

| Deconstruction |

Precedent |

Background |

Key insights |

Industry |

Governance |

Primary form of change |

| 1) Modularized machine-readable contracts |

Standardized Mortgages |

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac wrote and mandated standardized mortgage contracts in the 1970s |

Government backed private agencies that created mortgage forms divided into two components: 1) uniform mortgages accepted by every state and 2) those that could not reach consensus called non-uniform. |

Real Estate |

Public-private |

Standardization |

| Mobile Standard Setting Organizations (SSOs) |

Information and Telecommunication (ICT) standardization efforts apply standards across the entire industry through the work of standard-setting organizations (SSOs) (i.e., a public-private partnership to crowdsource and implement common technical standards across competing firms) |

SSOs are self-governed industry associations of competing firms that collectively select and adopt uniform technical standards to ensure compatibility and interoperability among products. To set a new standard, SSOs typically require members to disclose related IP. The SSO then determines the best solution to implement as the common standard across the market allowing them to achieve scale while incentivizing individual innovators to compete in the creation of better technology. SSO processes are revised and improved with government input, through membership of multiple agencies in the SSO and enforcement actions from the DOJ and FTC. |

Finance |

Public-private |

Centralization |

| 2) Payment infrastructure |

Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) |

Cooperation from many different players to work together to create a shared messaging service that provides improved services to customers and enables swifter transactions around the globe |

A group of 239 private financial institutions came together to develop a centralized communication system with codes that allowed banks to digitize process around transferring money. It was a member owned cooperative institution owned by shareholders (~3,500 financial institutions across the world are shareholders) but operated as a company with full time employees and CEO. The governance is a board of 25 representatives from the member banks, overseen by the ECB and central banks of the G10 countries where each nation’s usage determines the number of board members that each country is allowed. |

Finance |

Public-private |

Centralization |

| Stripe |

Revolutionized digital payment systems by creating a secure, standardized infrastructure that simplified bank connections for developers, enabling easier and more uniform tool development and reducing complexity in payment processes. |

The solution worked because they targeted a specific consumer (the developers) and need (payment infrastructure) and offered tailored benefits that worked. By offering simple, well-documented APIs, Stripe made it easier for developers to integrate payment processing into applications making it more convenient for consumers to make purchases and reducing cart abandonment rates. This precedent enabled a shared technological base across competing firms via a third party that enabled swifter innovation and development in an industry with large, slow-moving incumbents. |

Finance |

Private |

Standardization |

| HL7 SMART on FHIR |

Influence of government regulation in driving towards technological standardization within healthcare and the interoperability of systems that the change has created. |

With the goal to create a modern standard for healthcare data exchange, it aimed to overcome the limitations of previous HL7 standards like versions 2 and 3, which were known for being inflexible and cumbersome. FHIR leveraged modern web technologies to enable flexible and lightweight data exchange. The development of HL7 FHIR required collaboration from various stakeholders, which ensured real-world applicability and industry best practices. HL7 International maintains FHIR, regularly releasing updates and extensions to address emerging healthcare challenges. |

Technology |

Private |

Standardization |

| State utility commissions |

Public utility commissions began with regulatory activity to reign in the railroad monopoly in the late 19th century. States have since created similar commissions to regulate a broader range of public utilities, including electricity, gas, and water, to ensure fair rates and reliable service. |

Public utilities balance the interests of consumers and utility companies by overseeing operations, approving rate changes, and enforcing policies. They protect consumers while ensuring the financial health of utility providers and present a model of regulation of necessary transactions infrastructure. |

Public services |

Public-private |

Centralization |

| Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) |

Before the FAA was created in 1958, the CAA and CAB shared oversight of civil aviation regulation and safety measures, and regulatory responsibilities between the two agencies. When the FAA replaced the CAA and CAB, the US established a common civil-military system for air navigation and air traffic control and assumed broader authority to reduce aviation hazards. |

The FAA consolidated fragmented regulatory functions of the CAA and the CAB into a single authority, providing a comprehensive and standardized approach to aviation oversight. The FAA has embraced technological advancements, improved safety and security measures, and navigated various challenges, demonstrating the FAA’s ability to adapt to and address the evolving technological landscape of the aviation industry. The FAA has been actively involved in redesigning the National Airspace System (NAS) to accommodate the growing demand for air travel. This initiative involves optimizing airspace, improving navigation procedures, and implementing advanced technologies to enhance capacity and reduce delays. The FAA’s role has since expanded to the regulation of drones and commercial space flights, responding to the rapid growth of drone technology, commercial space travel, and cybersecurity. |

Logistics |

Public-private |

Centralization |

Legend: These precedents were used to directly support the final creative combination solutions. Descriptors were developed by the research team and described on the precedent briefs.

Exhibit a1: Workshop Participants and Steering Committee Members

Workshop Participants

| Name |

Description |

| Kenneth Favaro, MBA |

Developer of precedents methodology |

| Stefanos Zenios, PhD |

Developer of precedents methodology, Stanford Graduate School of Business |

| Kevin Schulman, MD |

Stanford University Schools of Medicine and Business |

| David Scheinker, PhD |

Stanford School of Medicine |

| Michael Murray, MS |

Former CFO of Blue Shield of California |

| Meghan Eluhu, MCiM |

Research team member |

| Bryan Kozin, MBA |

Research team member |

| Brooke Istvan, MBA |

Research team member |

| Perry Neilsen |

Research team member |

| Walter Winslow, MBA |

Research team member |

| Steering Committee Members |

|

|

| Name |

Description |

| Jacob Asher, MD |

Former CMO, multiple health plans |

| Matt Eyles, MPP |

Former CEO, AHIP |

| Kenneth Favaro, MBA |

Developer of precedents thinking methodology, Chief Strategy Officer, BERA Brand Management |

| Goutham Kandru |

Gates Ventures, associate director US healthcare |

| Robert Kaplan, PhD |

Harvard Business School |

| Ernest Ludy |

Former CEO, Medstat |

| Michael Murray, MS |

Former CFO of Blue Shield of California |

| Kavita Patel, MD, MSHS |

Stanford University School of Medicine |

| Barak Richman, PhD, JD |

George Washington School of Law |

| David Scheinker, PHD |

Stanford School of Medicine and Engineering |

| Kevin Schulman, MD |

Stanford Schools of Medicine and Business |

| Will Shrank, MD |

Former CMO, Humana |

| James Weinstein, MD |

SVP Microsoft Healthcare |

| Stefanos Zenios, PhD |

Developer of precedents thinking methodology, Stanford Graduate School of Business |

|

|

|

|

Exhibit a2: Full Precedents List

| Precedent |

Explanation |

Digitization,

Standardization, or Centralization? |

Public vs private vs partnership? |

| ATM Machines |

ATM Machines allow consumers to withdraw cash from any machine in the country using their debit card |

Digitization |

Private |

| ATM Networks |

ATM networks allow banks to communicate across regions and contracted networks in order to validate and process ATM requests for an additional fee |

Standardization |

Private |

| P&C insurance |

Property and casualty insurance to consumers is structured with standard minimum and fault formulas. Individual

contract rates are not typically negotiated |

Standardization |

Private |

| Medicare PPS |

The Medicare BBS determines fixed bundled payments to hospitals based on

geographic factors, patient case mix,

and DRGs |

Standardization |

Public |

| State of MD all-payer rate setting |

State (the HSCRC) sets rates for healthcare services that all providers receive from all payers |

Standardization |

Public |

| Medicare Advantage Generally |

Privately administered Medicare plans reimbursed through capitation at the federal level, allowing private payers to manage the plans locally in whatever way will maximize cost savings |

Standardization |

Public-Private |

| NHS standard contracts |

All of NHS uses the same contracts (single payer and single provider system makes this easy) |

Standardization |

Public |

| Direct contracting employer – provider (i.e., centers of excellence) |

Large employers are contracting directly with large providers to get guaranteed rates especially for specific high-cost procedures |

Centralization |

Private |

| CMS 1500 form |

CMS’s attempted common / standard claims form (used for all Medicare FFS and suggested to be used by private payers but it is mostly not used) |

Standardization |

Public |

| Uniform Mortgage forms

for Fannie Mae/Freddie

Mac |

In 1971, the two held the first public meeting to begin their efforts to standardize. This proved to be an iterative process with public meetings and community comment periods. There was disagreement over all components so both provided similar standardized mortgage forms and have specific pieces tailored to their guidelines |

Standardization |

Public-Private |

| OTC derivatives contracts |

In 1985, the ISDA and published a list of agreed-upon definitions and terms for contracts, covering a wide range of topics including floating amounts and default and termination provisions. ISDA also published a Master Agreement (MA) template in 1987, with updates in 1992 and 2002. |

Standardization |

Private |

| Tax forms |

1040 form created in 1917, IRS created in 1953 which audited and ensured up to date standard forms |

Standardization |

Public |

| Credit card applications |

Credit card applications are not standardized. Different credit cards are allowed to use different components of information to make a decision on approval. However, there are standard elements. For example, all lenders may consider a FICO score and all credit card agreements must include a “Schumer box” which details fees associated with the card as required by the Truth in Lending Act to be presented in a standardized format |

Standardization |

Private |

| Walt Disney World Ticketing |

Rather than pay for each experience at

Disney individually (like FFS), Disney Goers will pay for a general ticket upfront with “special” experiences and perks being paid on an individual basis. Tickets and experiences can be bundled for a few days or seasonally depending on the park goers preference. |

Digitization |

Private |

| Search Engines Algorithms |

Search engines use a variety of factors and algorithms to predict which searches are most relevant to the user’s request; this process has become increasingly sophisticated and sponsor-based as these platforms have developed. However, many firms will “hack” these algorithms by using SEOfavorable components on their websites in order to get higher rankings |

Digitization |

Private |

| Life Insurance policies |

Purchasers of life insurance are the people being directly insured themselves, no network negotiations |

Standardization |

Private |

| Online Gambling |

Originating as digitally posted sports books in 1995, private companies took advantage of lax gambling restrictions in Caribbean countries to establish online betting exchanges. CryptoLogic in 1995 allowed monetary transactions over the internet, which allowed the entire betting transaction to occur automatically on client websites. Note: the legality of online betting remains controversial |

Digitization |

Private |

| Streaming Services Analytics |

Large streaming services need to perform “content validation” in order to determine which content is worth purchasing/financing and what can be cut from their portfolio without losing a large percentage of subscribers |

Digitization |

Private |

| TV Residuals

Standards/Structure |

Residuals are paid to union members for continuously shown media. Residuals are calculated based on a variety of factors, including guild membership, initial payment, time spent, type of production, and foreign vs domestic market |

Standardization |

Private |

| TV Residuals Payments (SAG AFTRA) |

SAGAFTRA Unions administer and negotiate TV residuals for its members who appear on TV |

Centralization |

Private |

| Fast Food Franchising |

Brand identity, trademarks, suppliers, and products are licensed to investors for a percentage of revenue in order to establish a local chain |

Standardization |

Private |

| Eventbrite |

Consolidates contracts with artists and vendors on a centralized platform and derives revenue from a percentage of the ticket sale |

Centralization |

Private |

| Residential Lease Agreements |

Property managers and landlords use standardize lease agreements |

Standardization |

Private |

| Banking clearinghouses |

Established between 1750 and 1770 as a place where the clerks of the bankers of the city of London could assemble daily to exchange with one another the cheques drawn upon and bills payable at their respective houses. Meant to reduce the risk of a member firm failing to honor its trade settlement obligations. |

Centralization |

Public |

| Digital ACH infrastructure |

Computer-based electronic network for processing transactions, usually

domestic low value payments, between participating financial institutions, automating the clearinghouse concept developed in the 1700s in London |

Digitization |

Public-Private |

| Apple Wallet |

Digital passes etc. collected across arious apps, emails, etc. into one central digital wallet |

Centralization |

Private |

| Stripe |

Stripe’s focus was to make it easier for developers to integrate payment processing into their websites and applications. They gained popularity and expanded its services globally at the forefront of developing and implementing new technologies in the payment space (i.e., simple checkout, support for various payment methods, tools for managing subscriptions and recurring payments) |

Standardization |

Private |

| TurboTax |

TurboTax has become the premier source for compiling and issuing annual

tax payments for both federal and state filings. Consumers can use a tool at no cost to help with filing tax returns |

Digitization |

Private |

| CommonApp |

CommonApp served to simplify the college application process by enrolling multiple institutions to the same college application questions and formats to make it easier on students and families |

Centralization |

Private |

| The Bar exam / association |

The Bar serves as a standardized set of requirements for legal professionals to be certified by in order to practice. Standardized nationally and tailored at the individual state level. The bar creates a repository of all certified lawyers |

Standardization |

Public |

| Online marketplaces (Indeed, amazon) |

Proliferated in the 21st century as a simple way to shop or share data online

in standard locations/sites with

standardized formats |

Centralization |

Private |

| Credit scores & loan preapproval |

Credit scores created by centralized providers serve as the measurement for financial services providers. FICO created in 1989, which is the basis for a credit score to determine approvals and preapprovals |

Standardization |

Private |

| Student loans / FAFSA |

FAFSA is a standardized form by which student loan decisions are made with key data elements that are shared to loan providers |

Centralization |

Public |

| Railroad infrastructure (Amtrak) |

A combination effort from government subsidized players and private entities enabled passenger rail transportation across the US to grow significantly |

Centralization |

Public-Private |

| Spam email (Phishing) |

Ever since the first spam email was sent over ARPANET in 1978, email clients have been trying to sort spam email using all sorts of sophisticated algorithms and big data analytics. However, spam emailers have used equally sophisticated systems in order to evade detection which has driven increasing reliance on technological innovation on both sides of the “spam war’ |

Digitization |

Private |

| Federal Direct Cost Reporting |

Within a higher ed institutions, “direct” costs for sponsored projects are individually itemized and tracked per project, even under the same principal investigator. When those costs are reported to the federal government for grant reimbursement, they are concatenated under 8 categories for billing simplification |

Standardization |

Public |

| Tech modularization

(Hardware – HP printers, Software – Enterprise software offerings) |

HP printers are a famous operations case study of modularization in production where HP can easily mass produce a bunch of printers and then just change the charging cable to sell them around the world |

Standardization |

Private |

| Quality metrics (state-based efforts to standardize) |

Healthcare quality metrics have exploded over the past 2 decades with thousands of different quality metrics providers are required to report to specific payers and regulatory bodies. There have been several states that have taken legislative action to standardize quality metrics and require that health plans use the standardized measures. For example, Minnesota’s 2008, Massachusetts 2010, and Oregon’s 2013 laws direct the development of standard sets of quality measures and mandate healthcare providers report on these measures and health plans do not require other metrics |

Standardization |

Public-Private |

| Eliminating upcoding in

MA |

There is a history of providers and payers “upcoding” in MA to get more money for a more risky population. The federal government reviewed MA codes compared to FFS codes and found a bunch of codes that were higher $ reimbursement that were overutilized and cut those codes / reduced their payment to be in line with average, etc.

where medically appropriate |

Standardization |

Public |

| Government contracts / RFPs / RFIs |

Government has a standard Request for proposal process for hiring vendors / contractors that allow the government to evaluate on set criteria and also a request for information (RFI) process to solicit input into law making from private sector associations as well as nonprofits and research institutes |

Standardization |

Public |

| Class pass / Doordash / Eventbrite |

A centralized app and payment that allows a consumer to choose from many options at many providers (e.g., for food, for workout classes) |

Centralization |

Private |

| Drinking water standards / wastewater standards |

The Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 was the first major U.S. law to address water pollution. Growing public awareness and concern for controlling water pollution led to sweeping amendments in 1972. As amended in 1972, the law became commonly known as the Clean Water Act (CWA). |

Standardization |

Public |

| FAA / air traffic control regulations |

There was some regulation from the 1930’s to the 1950’s with the FAA creation taking place in 1958 to ensure safety and things were initially fragmennted. The FAA consolidated and became part of DOT in 1967 to ensure a coordinated transportation system. |

Centralization |

Public-Private |

| GAAP / Capitalization standards |

The SEC was created after the crash of

1929 with the first mention of GAAP in 1936. The goal was to achieve conformity with proper accounting, full disclosure and comparability. |

Standardization |

Public |

| Car emissions standards |

Congress passed the landmark Clean Air Act in 1970, which gave the newly formed EPA the legal authority to regulate pollution from cars and other forms of transportation. |

Standardization |

Public |

| Gas octane levels |

Combination of private marketing in the 1960’s to standardize offerings to consumes and the Clean Air Act from the EPA phasing out lead gasoline. |

Standardization |

Public-Private |

| W2 vs. 1099 / employee vs. contractor distinction |

The 1099 tax form has been around since 1917. Labor laws in the 1930’s and additional regulation in the 1970’s was passed focused on contractor vs. employee distinction with separate forms |

Standardization |

Public |

| Fishing (Fish and Wildlife) as technology increased |

As early as 1871, Spencer Fullerton

Baird, Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution flagged depletion and created the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). Various regulation pre-dated the formation of the NOAA but then NMFS was consolidated under NOAA which was more focused on conservation and established regulations and quotas that reduced overfishing |

Centralization |

Public |

| AI in finance / open banking rule |

CFPB issued RFI on AI in 2021; 2022 issued notice highlighting discrimination in models; June 2022, the American Data Privacy Protection Act (ADPPA); also in 2022 Biden issued AI Bill of Rights, which set out provisions to give consumers more control over and protetction of their data |

Standardization |

Public-Private |

| Voting machines (Analog to digital transition) |

Ballots were originally paper and have been converted to digital in many places. Mail-in voting is still analog but counted by machines. This is an example of a hybrid system |

Digitization |

Public-Private |

| Shopify |

Collation and tracking of online purchases. Helped centralize online shopping and shipping information for consumers |

Standardization |

Private |

| Blockchain identity verification (Truework) |

Traditionally, identity and employment verification were extremely tedious for processes like mortgages. Truework created a digital verification of information and maintenance of that information for future use |

Digitization |

Private |

| Online air tickets |

Tickets used to be purchased at counters in airports and travel agencies then moved online and centrtalized by Google flights |

Digitization |

Private |

| DocuSign |

Example of digitizing an analog process of signing documents but doing so in secure and trusted environment |

Digitization |

Private |

| RFID in Retail Inventory Management |

Example of multiple stakeholders coming together in the private sector to develop the technology in a lab at MIT and then commercialize it for digital tracking and tagging of inventory and shipped goods that can be interoperable |

Digitization |

Private |

| Online retail return |

As shopping moved digital, so did returns. Amazon is a great example of simplification for the user on top of this digital process (you can just walk into a UPS store with whatever item you want to return and scan a QR code, don’t even have to box anything up). |

Digitization |

Private |

| DSCSA for drug tracking |

Enacted in 2013 to focus on transparency and tracking of drugs through the supply chain. It improved safety, visibility, tracking and availability data |

Standardization |

Public |

| Digital fast food menu boards and OS (e.g., Toast) |

Analog process made digital. There was also standardization and cataloging of items. Tedious process with tons of combinations became streamlined through an easy to update digital platform. |

Digitization |

Private |

| HTML/early internet architecture |

The first internet was invented by Tim

Berners-Lee, a physicist at the

European Laboratory for Particle Physics (CERN), who wanted to share

research ideas freely with his collaborators in other countries. This was the first rendition of “hypertext” which later became HTML, the language of coding internet websites. HTML was further developed and legitimized by the Internet Engineering Task Force, led by other scientists and engineers trying to standardize HTML to maximize its benefit to the academic community. This is an example of private standards slowly incorporated by larger working groups until it established as the global standard |

Standardization |

Public-Private |

| Lean Manufacturing |

Lean manufacturing is a production method that tries to eliminate waste by limiting excess production and inventory to match total demand and focus on quality control and

efficiency at individual steps in the manufacturing process |

Standardization |

Private |

| Automated passport control |

Automated border entry for travelers meeting entry requirements improves user experience and reduces manual bureaucratic steps |

Digitization |

Public-Private |

| Usage-based Billing for

Utilities |

Automated billing and payments options offered by utility companies that can be set up directly with customer bank accounts or credit cards. This improves efficiency, likelihood of utilities getting paid and hassle for users |

Standardization |

Public-Private |

| Accounts Receivable Securitization |

Been in place since the 1980s, but low penetration vs. mortgages. Reliable and cost efficient funding through accounts receivable securitization + receivables insurance can reduce credit performance uncertainty, mitigate catastrophic risk and enhance cash flow |

Centralization |

Private |

| Digital Identity

Verification (e.g., face scans) |

Fast form of secure identity verification (i.e., hard to copy a whole face). There are systems sharing information used in more and more locations like airports to expedite security processes. |

Digitization |

Private |

| ICT Cellphone |

TIA has a history of encouraging disclosure of IP to ensure standards to

accelerate interoperable / connected development |

Centralization |

Private |

| Tesla (DTC marketing) |

Tesla eliminated the dealer as a secondary margin taker to increase their ability to make their cars more affordable |

Standardization |

Private |

| Tesla (supply chain innovation) |

Unlike traditional automakers, Tesla vertically integrated several aspects of its supply chain, including manufacturing key components like batteries and electric motors in-house |

Standardization |

Private |

| Enterprise resource planning systems in manufacturing |

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems in manufacturing emerged in the 1990s as a response to the need for integrated solutions that could manage various business processes, from production and inventory to finance and human resources. ERP systems aimed to eliminate data silos and enhance overall operational efficiency. ERP systems revolutionized manufacturing by providing a unified platform for managing and analyzing business processes. They streamlined operations, improved communication between departments, and enhanced decision-making through real-time data insights. |

Digitization |

Private |

| Two-factor authentication |

Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) has its roots in the information technology and cybersecurity domains. The concept gained prominence as a response to the vulnerabilities associated with traditional

username and password systems. The idea is to add an additional layer of security by requiring users to provide a second form of identification beyond just a password. It has enhanced cybersecurity by adding an extra layer of protection against unauthorized access. By requiring users to provide a second form of identification, such as a temporary code from a mobile device, 2FA has reduced the risk of data breaches, identity theft, and unauthorized system access. |

Digitization |

Private |

| SWIFT (Society for

Worldwide Interbank

Financial

Telecommunications) |

Global provider of secure financial messaging services. It facilitates standardized communication and transactions b/w financial institutions worldwide and streamlines financial processes (e.g. fund transfers, payment instructions, etc.). It was started by a group of private banks who recognized the need for a standard messaging service and then grew to include government central banks |

Centralization |

Public-Private |

| Contactless fare payments (MTA in NYC, BART in SF, etc.) |

Public transportation systems allow for contactless cards/mobile payment apps enabling better customer experience |

Digitization |

Public-Private |

| Freelance Platforms (Upwork, Fiverr, etc.) |

Marketplaces for businesses to find and hire independent professionals for temporary jobs or projects based on select criteria (skills, experience, location, etc.) secures transactions and ensures payment and quality work |

Centralization |

Private |

| Hotel express checkout |

Hotels allowing guests to skip traditional checkout process and receive an electronic invoice instead to improve user experience and reduce work for the hotel |

Digitization |

Private |

| Minor software updates |

Software companies conduct automatic updates for minor software releases (e.g. iOS updates). This streamlines the software maintenance process without requiring explicit prior authorizations for security updates or bug fixes |

Digitization |

Private |

| Common Course

Registrations |

Direct enrollment for classes that don’t require prior authorization to reduce burden for schools and students |

Digitization |

Private |

| Peoplesoft / HR software |

Simplified authorization processes for routine time off requests and low-risk HR processes |

Digitization |

Private |

| Renewal of government licenses |

Government implemented automatic renewal processes for licenses with straightforward renewal criteria (e.g. driver’s licenses, business licenses, hunting/fishing licenses, etc.), reducing burden for both the government and users |

Standardization |

Public |

| Napster |

User created content from centralized data (i.e., playlists from central repository of songs) |

Centralization |

Private |

| HL7 FHIR |

Industry created interoperability standards that enable easy data exchange and developer consensus |

Standardization |

Private |

| Roth IRA |

Innovation on the 401K that offers tax advantages |

Standardization |

Public-Private |

| State utility commissions |

Regulation to ensure fair rates, reliable service, and compliance with standards. They balance the interests of consumers and utility companies by overseeing operations, approving rate changes, and enforcing policies. |

Centralization |

Public-private |

Exhibit a3: Summary of 26 Precedent Briefs

Exhibit a4: Example of 2 Pager Precedent Briefs

Exhibit a5: Original prompt used for ChatGPT precedents brainstorm

“I am trying to create a list of examples where industries have innovated to improve nonstandard administrative processes to streamline a set of services and remove costs. I want to focus on administrative spend reduction in particular with target reductions in contract complexity, billing process complexity, and documentation & regulation standards as examples. I don’t want to focus on applications to patient care. I want to apply a set of takeaways from these other industry examples to healthcare to try to figure out how to remedy the rising healthcare costs in the US. Please provide examples with a title of the precedent, a quick summary of the history/definition of the change, the industry it was relevant to, the impact to that industry, and the potential application to healthcare. Please provide 25 examples.”

References

- Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US Health Care System: Estimated Costs and Potential for Savings. JAMA 2019; 322(15):1501-1509.

- Sahni NR, Mishra P, Carrus B, Cutler Administrative Simplification: How to Save a Quarter-Trillion Dollars in US Healthcare. McKinsey & Company. October 20, 2021. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/administrative-simplification-how-to-save-a-quarter-trillion-dollars-in-US-healthcare

- Sandling J, Richman BD, Favaro K, Zenios SA, Schulman KA. Reducing Administrative Costs in U.S. Healthcare: Using Precedent Thinking to Develop Pathways to Innovative Solutions. Competition Policy International. 2024. Available from: https://www.pymnts.com/cpi-posts/reducing-administrative-costs-in-u-s-healthcare-using-precedent-thinking-to-develop-pathways-to-innovative-solutions/. Accessed 2024 Feb 20.

- Zenios S, Favaro K. Precedent Thinking Method. Harvard Business Review forthcoming 2024.

- Gee E, Spiro T. Excess Administrative Costs Burden the U.S. Health Care System. Center for American Progress. 2019. Available from: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/excess-administrative-costs-burden-u-s-health-care-system/. Accessed 2024 Jun 2.

- “The Role Of Administrative Waste In Excess US Health Spending, ” Health Affairs Research Brief, October 6, 2022. DOI: 10.1377/hpb20220909.830296. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/briefs/role-administrative-waste-excess-us-health-spending.

- Woolhandler S, Campbell T, Himmelstein DU. Costs of Health Care Administration in the United States and Canada. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003. 349(8):768–75.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Yong PL, Saunders RS, Olsen L, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2010. PMID: 21595114.

- Cutler D. Reducing Administrative Costs in U.S. Health Care. The Hamilton Project. 2020. Available from: https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/policy-proposal/reducing-administrative-costs-in-u-s-health-care. Accessed 2024 Mar 20.

- Cutler D, Wikler E, Basch P. Reducing administrative costs and improving the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2012 Nov 15;367(20):1875-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1209711. PMID: 23150956.

- Tseng P, Kaplan RS, Richman BD, Shah MA, Schulman KA. Administrative Costs Associated With Physician Billing and Insurance-Related Activities at an Academic Health Care System. JAMA. 2018;319(7):691–697. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.19148

- Schulman KA, Nielsen PK Jr, Patel K. AI Alone Will Not Reduce the Administrative Burden of Health Care. JAMA 2023; 330(22):2159-2160.

- Scheinker D, Richman BD, Milstein A, Schulman KA. Reducing administrative costs in US health care: Assessing single payer and its alternatives. Health Serv Res. 2021 Aug; 56(4):615-625.

- NHE Tables | CMS. 2023. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/nhe-fact-sheet#:~:text=NHE%20grew%204.1%25%20to%20%244.5. Accessed 2024 Mar 7.

- 2023 Peterson-KFF tracker. Peter G Peterson Foundation. Available from: https://www.pgpf.org/blog/2023/07/how-does-the-us-healthcaresystem-compare-to-other-countries. Accessed 2024 Mar 7.

- ChatGPT. Chat.openai.com. OpenAI; 2023. Available from: https://chat.openai.com/. Accessed 2023 Oct 10.

- Information on the Change Healthcare Cyber Response. United Health Group. Available from: https://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/ns/changehealthcare.html. Accessed 2024 Mar 20.

- 2023 AMA Prior Authorization Physician Survey. American Medical Association. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/prior-authorization-survey.pdf. Accessed 2024 Mar 10.

- Kyle MA, Frakt AB. Patient administrative burden in the US health care system. Health Serv Res. 2021 Oct;56(5):755-765. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13861. Epub 2021 Sep 8. PMID: 34498259; PMCID: PMC8522562.

- Han E. What Is Design Thinking & Why Is It Important?. Business Insights Blog. Harvard Business School Online; 2022. Available from: https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/what-is-design-thinking. Accessed 2024 Mar 20.

- Shepherd, D.A., Patzelt, H. (2018). Prior Knowledge and Entrepreneurial Cognition. In: Entrepreneurial Cognition. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71782-1_2

- Sandling J, Richman BD, Favaro K, Zenios SA, Schulman KA. Ensuring Access To Generic Medications In The US. Competition Policy International (pyments.com). 2024.

- National Research Council (US) Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. Chapter 6, Building a 21st-Century Emergency Care System. Available from: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/12750/chapter/7

- Himmelstein DU, Lawless RM, Thorne D, Foohey P, Woolhandler S. Medical bankruptcy: Still common despite the Affordable Care Act. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014. 14:556. Available from: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12913-014-0556-7.pdf

- Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Care Fragmentation in the Postdischarge Period: Surgical Readmissions, Distance of Travel, and Postoperative Complications. Ann Intern Med. 2020. 172(4):289-297. Available from: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M19-2818

- 2020 CAQH Index: A Report of Healthcare Industry Adoption of Electronic Business Transactions and Cost Savings. Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare; 2020. Available from: https://www.caqh.org/sites/default/files/explorations/index/2020-caqh-index.pdf

- CAQH White Paper: The Hidden Cause of Inaccurate Provider Directories. Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare; 2019. Available from: https://www.caqh.org/about/newsletter/2019/caqh-white-paper-hidden-cause-inaccurate-provider-directories

- Choosing a Medigap Policy: A Guide to Health Insurance for People with Medicare. Available from: https://www.medicare.gov/publications/02110-medigap-guide-health-insurance.pdf. Accessed 2024 Jun 1

- Individual Health Insurance Plans & Quotes California. Health for California Insurance Center. Available from: https://www.healthforcalifornia.com/individual-health-insurance. Accessed 2024 Jun 1