Sumate Permwonguswa, Assumption University, Thailand; Chadi Hajar, Paul Cook, Breanna Wong, Megan Mccarthy, Jiban Khuntia, Errol Biggs, University of Colorado Denver

Contact: Sumate Permwonguswa, Sumateprm@msme.au.edu

Abstract

What is the message?

Empowerment and satisfaction of physicians are two key challenges to telehealth adoption. The survey found that telehealth is most empowering and satisfying for hospital-based providers, particularly in urban settings. Satisfaction varies with several demographic factors including gender, structural distance, and age.

What is the evidence?

Survey of 31 respondents from hospitals, providers, clinics, and physician offices in the Denver area.

Submitted: December 18, 2017. Accepted after review: March 6, 2018

Cite as: Sumate Permwonguswa, Chadi Hajar, Paul Cook, Breanna Wong, Megan Mccarthy, Jiban Khuntia, Errol Biggs. Provider Empowerment and Satisfaction with Telehealth: Exploring Variation across Structural and Demographic Factors. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 3, Issue 1.

Introduction

The lack of timely access to care is a constant criticism of healthcare in the United States and other countries.1, 2 For example, often a patient may be admitted to an emergency unit and needs to be seen by his or her primary care physician but the physician may not be available. Similarly, a psychiatrist may be too busy to attend to a patient when he or she has had a traumatic experience or a panic attack. Beyond these examples, there are significant populations living in rural areas which lack convenient access to healthcare.

Critically, in the current healthcare models, doctors often do not feel that they are participative or a key element of the patient’s treatment process, unless it is invoked through the institutional models. 3, 4 For instance, a patient may be seen by any doctor in a hospital or any specialist in a clinic, as needed by the common procedure terminology based diagnosis or a disease identification process. The concept of doctors who wish to “treat my own patient”, or patients to feel as though “I need to see my own doctor” is often diluted in current healthcare institutional models.

Telehealth is emerging as a plausible solution to some of the access issues in the current healthcare system. Telehealth refers to remote clinical services provided to patients by physicians or health providers through telecommunication technology (i.e., video chat, telephone), which may or may not involve medical intervention. 5 Telehealth gives health care providers the capability to assess, diagnose, and treat patients in remote locations.

Market wise, significant growth in the telehealth industry is predicted in the next few years. The use of telecommunication technology enables patients in remote locations to receive care and medical expertise efficiently, in real time, and without travel. Broadly, telehealth is evolving as a critical component of the healthcare crisis solution, and has the potential to remarkably impact various problems within our current healthcare system: access to care, cost-effective delivery, and distribution of limited providers.

Irrespective of the perceived potential for telehealth in healthcare delivery, widespread adoption is still lacking. Only 42% of hospitals in the United States have adopted telehealth; most of them are teaching hospitals and are members of a larger health system. 6 Some suggest that factors such as reimbursement and license issues are reasons for lack of adoption, while others allude to the issues relevant to providers use, expected results, and social influence. 7, 8 Amongst other challenges, clinicians’ acceptance and promoting engagement in health maintenance and health care in a telehealth-enabled environment have been touted as major challenges for widespread adoption of telehealth by providers. 9, 10

Understanding when clinicians accept or do not accept telehealth is a particularly important issue. It is important to explore whether providers believe that telehealth is helping them in any significant manner. Motivated providers can lead and influence others to use telehealth.

This study considers provider empowerment and satisfaction in order to explore telehealth adoption, and explores how these two factors vary across structural context (e.g., hospital vs. non-hospital including clinics and office), hospital settings (urban vs. rural), the structural distance of the doctor/provider in the organization, and the providers’ demographics (e.g., age and gender). Section 2 provides the theoretical approach to the study. Section 3 provides details on the survey conducted. Section 4 provides the results; the core finding is that telehealth is most empowering and satisfying for hospital-based providers, particularly in urban settings, while satisfaction varies with several demographic factors including gender, structural distance, and age. Section 5 concludes with insights from the study.

Provider Empowerment and Satisfaction in Telehealth Context

Empowerment, as a broad concept, refers to a process by which individuals, groups, or organizations gain control over matters that are of interest to them. 11 Researchers have suggested that empowerment is effective in dealing with job- or work-related outcomes,12 improving employee satisfaction, 13 and providing discretion over work for those who feel powerless. 14 Hence, doctor empowerment is a capacity-building process either in the self-practice or in the practicing hospital. Empowered doctors would take more responsibilities, and would have greater influence and control over their patients’ health management process.

Studies suggest that doctor satisfaction is related to quality of care 15, 16 and patient satisfaction. 17 Doctor satisfaction refers to the physician’s feeling in terms of satisfaction in their practice. 16 When a doctor is dissatisfied with the practice, the quality of care from that doctor can deteriorate and he or she is likely to miss appointments and affect patient satisfaction. 18

The relevance of provider empowerment and satisfaction in the telehealth context stems from two sources. First, telehealth helps healthcare providers reduce costs while increasing quality of care. 5 Patients can be taken care of more efficiently using telehealth. For example, patients can stay home, avoiding the waste of time spent on a long-distance commute. Second, if providers do not feel satisfied, they are less comfortable using telehealth to diagnose and treat their patients.15 Thus, provider empowerment is an essential point in the loop of patient care through telehealth.

We expect that the feeling of empowerment and satisfaction will vary across different contextual and demographic factors. We noted key contextual factors above. We focus on the issues of hospital and non-hospital (clinic, office) setting, urban and rural setting, the structural distance of the doctor/provider in the organization, and the providers’ demographics (age and gender).

Telehealth demand and support in the hospital vs. non-hospital setting vary. Use of telehealth in a hospital itself may be supported by a set of staff, and may have other support services. Such support may not be available in a physician’s office or independent clinic. However, hospitals may have other criteria such as scheduling the equipment beforehand, or dependency on other departments to use the telehealth equipment. A physician’s office or clinic may be more independent while making telehealth use decisions. A doctor may have to be in a situation to simply switch on the equipment and begin talking to a patient in the office. However, in an office environment, the use of telehealth may not be warranted, unless the office or clinic is operating with a set of other providers as a part of the network.

A widely discussed value proposition for telehealth use is for remote settings in rural areas. However, contrary to this foreseen opportunity, telehealth is not being adopted as rapidly as anticipated in rural areas. 19 Possible reasons may be the sustenance of the telehealth equipment, support, or availability of required bandwidth. On the contrary, these issues are well taken care of in an urban setting. In addition, telehealth has high potential to reduce patient travel, bridging the care gap across two urban locations and availability of resources to remote locations in odd hours (e.g., a psychiatrist connecting to a remote location from a main hospital during the night for a suicidal case). Thus, it is imperative to explore the differences in empowerment and satisfaction across urban and rural areas.

A third factor we explore is the position of the doctor in the organization, and we coin this as the ‘structural distance’. Existing literature suggests that structural distance influences decision-making and independence in practice. 20, 21 Higher distance might suggest lack of support or lack of team work; but it also suggests that the doctor’s position in the care delivery setting is quite unique and independent. 20 Decisions taken in an independent and unique position in care delivery influences the feeling of ‘ownership’ or ‘responsibility’ for the patients. In other words, higher structural distance and subsequent independence in care delivery is an aspect of feeling that ‘I am treating my own patient’—and thus, is expected to influence empowerment and satisfaction better than doctors with lower structural distance in their respective organizations.

Finally, as suggested in literature, the scope of self-efficacy regarding any health information technology use is dependent on the demographic factors. We expect this to be consistent regarding empowerment and satisfaction with telemedicine, and thus, explore how it varies across male and female providers, and across different age groups.

Survey and Analysis

We used a primary data collection method, and existing construct operationalization from prior studies. The items were adapted to the context of this study. In the questionnaire, all the items are measured on a seven-point Likert scale, except the age, gender, and contextual questions.

The key variables–empowerment and satisfaction–were measured using three and five measurement items respectively. These measurement items were used in prior literature and have been proven for reliability and construct validity.22, 23, 24, 25 Similarly, the structural distance orientation was measured using five items that were used and verified for reliability and validity in prior literature. 20

We developed our sample frame by exploring hospitals, providers, clinics and physician offices in the Denver area. Usable data was collected from 31 respondents using telehealth in their healthcare organizations.

The analysis mainly consists of t-test comparisons and ANOVA for empowerment and satisfaction measures across other variables. We present the results both empirically and graphically in figures 1 and 2. Our key findings are summarized and discussed in the next section.

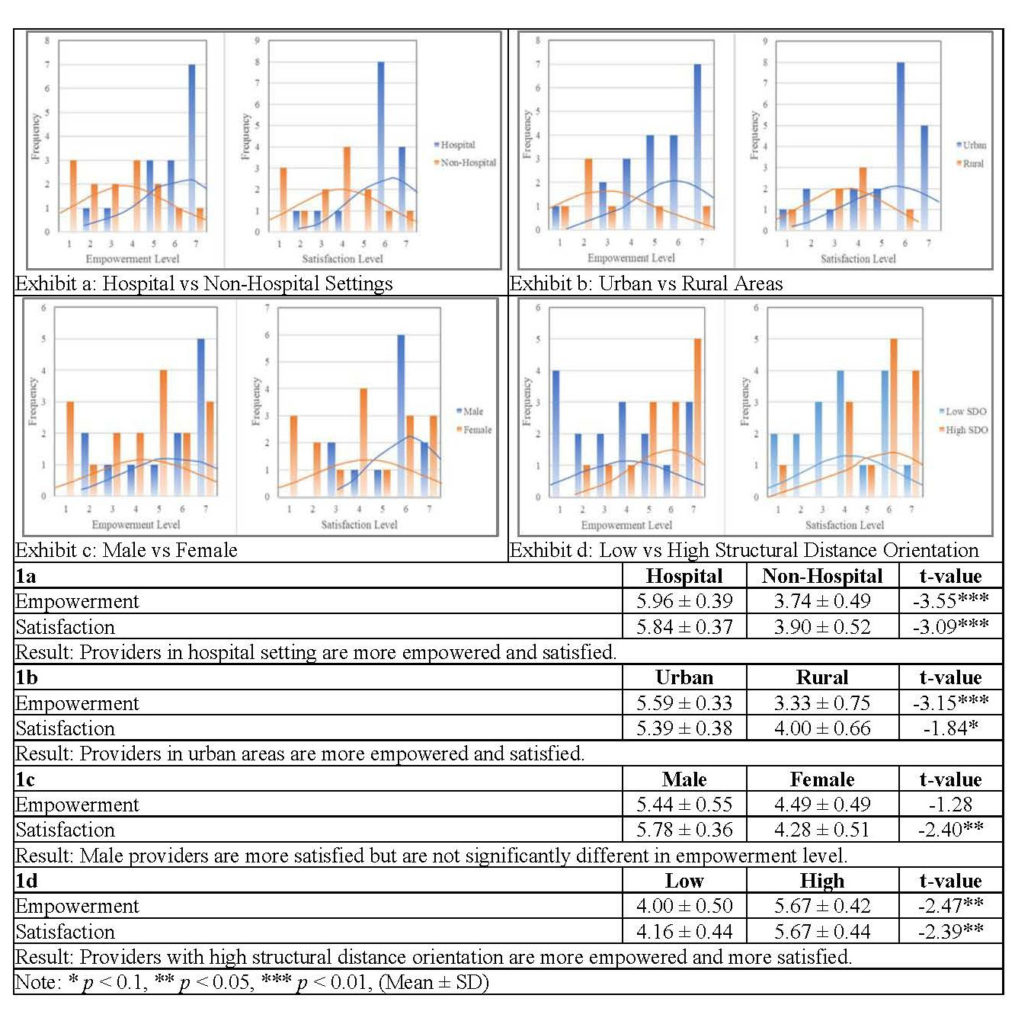

Figure 1: Comparisons of Empowerment and Satisfaction with Telehealth amongst Different Factors

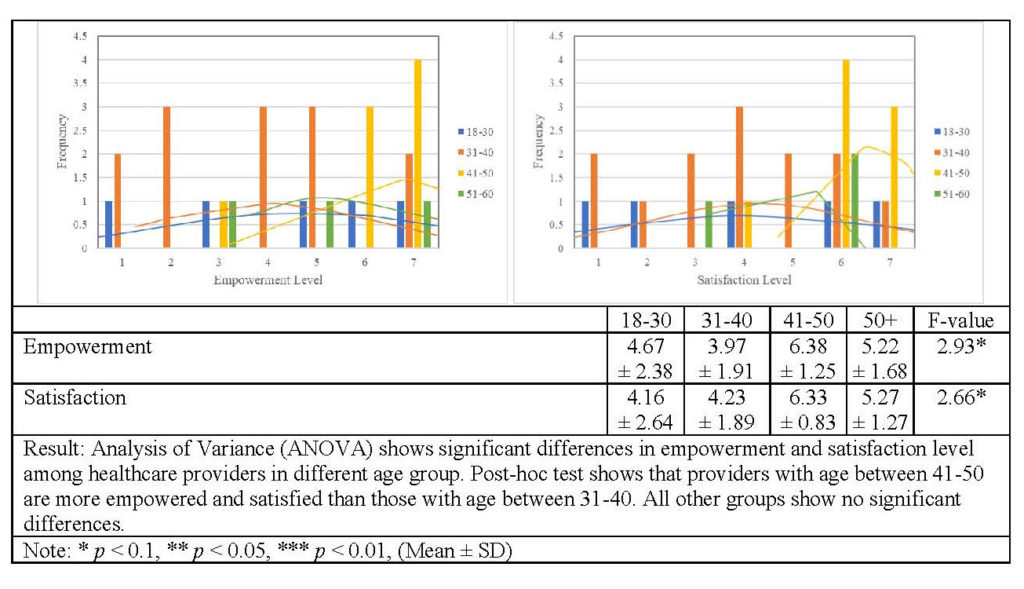

Figure 2: Empowerment and Satisfaction of Telehealth Providers Differentiated by Age

Discussion

First, we found that hospital-based use of telehealth is highly empowering and satisfying for providers (Figure 1 exhibit a). Plausibly, providers and doctors in a hospital setting do not have to pull the equipment and plug it in. They have a support system and other infrastructure which lead to a better appreciation of the utility of telehealth compared to non-hospital based providers in an office or clinic setting.

Second, by urban-rural setting differentiation, we found that urban area users have higher empowerment and satisfaction scores than rural providers (Figure 1 exhibit b). Possibly, as noted earlier, rural providers are still not leveraging much from telehealth, regardless of the widely-hyped potential in telehealth for rural populations. In addition, rural providers may have concerns, issues and challenges such as bandwidth and internet access round the clock for telehealth use. However, urban providers can better appreciate the value proposition of telehealth, leading to higher empowerment and satisfaction scores. Undoubtedly, more than the ‘remote access’ value proposition of the telehealth, the ‘just-in-time’ or ‘just-in-place’ care delivery provisions through telehealth are becoming highly beneficial to urban doctors.

Several demographic factors are relevant. Males feel better about telehealth use (Figure 1 exhibit c). This may be related to the self-efficacy variations with technology use suggested in early literature. 22 Providers with higher structural distance are more empowered and satisfied with telehealth (Figure 1 exhibit d). Finally, the age group of 41-50 is more empowered and satisfied with telehealth use (Figure 2). This could be explained by differences that come with age and years of experience such as an increased satisfaction and desire to treat patients just-in-time or increased independence. Overall, providers with more independence are enjoying telehealth more.

An explanation for the age effect could be that with higher age and experience, perhaps the satisfaction or feeling to treat a patient just-in-time is higher. This means lone-wolves are enjoying telehealth more. Obviously, independence and uniqueness in practice is a solid explanation for this finding.

In conclusion, empowerment and satisfaction are two key challenges to telehealth adoption. Variance across these two dimensions may help explain the variance in telehealth adoption. Our study establishes and demonstrated this variance across hospital settings, demographics and structural distance of providers. Future studies may explore the nuanced impact of these variations on telehealth adoption and performance.

References

- Currie, W. L. 2009. Integrating Healthcare. W.L. Currie and D. Finnegan (eds.). Integrating Healthcare with Information and Communications Technology. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2009:3-34.

- Mays GP, Smith SA, Ingram RC, Racster LJ, Lamberth CD, Lovely ES. Public Health Delivery Systems: Evidence, Uncertainty, and Emerging Research Needs. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(3):256-265.

- Marmor T, Oberlander J, White J. The Obama Administration’s Options for Health Care Cost Control: Hope Versus Reality. Annals of Internal Medicine 2009;150(7):485-489.

- Romanow D, Cho S, Straub DW. Riding the Wave: Past Trends and Future Directions for Health It Research. MIS Quarterly. 2012;36(3):iii-x.

- McLean S, Protti D, Sheikh A. Telehealthcare for Long Term Conditions. British Medical Journal. 2011;342:d120.

- Kahn JM. 2015. Virtual visits—confronting the challenges of telemedicine. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(18):1684-1685.

- Kruse CS, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating Barriers to Adopting Telemedicine Worldwide: A Systematic Review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2016;24(1):4-12.

- Lim JH, Stratopoulos TC, Wirjanto TS. Sustainability of a Firm’s Reputation for Information Technology Capability: The Role of Senior It Executives. Journal of Management Information Systems. 2013;30(1):57-96.

- Bartz CC, Hardiker N. Promoting Engagement in Health Maintenance and Health Care in a Telehealth-Enabled Environment. W. O’Donohue, L. James and C. Snipes (eds.). Practical Strategies and Tools to Promote Treatment Engagement. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017:91-104.

- Wade VA, Eliott JA, Hiller JE. Clinician Acceptance Is the Key Factor for Sustainable Telehealth Services. Qualitative Health Research. 2014;24(5):682-694.

- Zimmerman, M. Psychological Empowerment: Issues and Illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23(5):581-599.

- Liao H, Toya K, Lepak DP, Hong Y. Do They See Eye to Eye? Management and Employee Perspectives of High-Performance Work Systems and Influence Processes on Service Quality. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2009;94(2):371.

- Hui MK, Au K, Fock H. Empowerment Effects across Cultures. Journal of International Business Studies. 2004;35(1):46-60.

- Kelley SW, Longfellow T, Malehorn J. Organizational Determinants of Service Employees’ Exercise of Routine, Creative, and Deviant Discretion. Journal of Retailing. 1996;72(2):135-157.

- Allen T, Whittaker W, Sutton M. Does the Proportion of Pay Linked to Performance Affect the Job Satisfaction of General Practitioners?. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;173:9-17.

- Richardson JE, Kern LM, Silver M, Jung HY, Kaushal R. Physician Satisfaction in Practices That Transformed into Patient-Centered Medical Homes: A Statewide Study in New York. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2016;31(4):331-336.

- Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, Burstin HR, Cleary PD, Brennan TA. Is the Professional Satisfaction of General Internists Associated with Patient Satisfaction?. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(2):122-128.

- DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Ordway L, Kravitz RL, McGlynn EA, et al. Physicians’ Characteristics Influence Patients’ Adherence to Medical Treatment: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychology 1993;12(2):93.

- Martin AB, Probst JC, Shah K, Chen Z, Garr D. Differences in Readiness between Rural Hospitals and Primary Care Providers for Telemedicine Adoption and Implementation: Findings from a Statewide Telemedicine Survey. The Journal of Rural Health. 2012;28(1):8-15.

- Avolio BJ, Zhu W, Koh W, Bhatia P. Transformational Leadership and Organizational Commitment: Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment and Moderating Role of Structural Distance. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2004;25(8):951-968.

- Liu SM, Liao JQ. Transformational Leadership and Speaking Up: Power Distance and Structural Distance as Moderators. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal. 2013;41(10):1747-1756.

- Deng X, Khuntia J, Ghosh K. Psychological Empowerment of Patients with Chronic Diseases: The Role of Digital Integration. Paper presented at: The 34th International Conference on Information Systems; 2013; Milan, Italy. http://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1051&context=icis2013. Accessed September 15, 2017.

- Estrada CA, Isen AM, Young MJ. Positive Affect Improves Creative Problem Solving and Influences Reported Source of Practice Satisfaction in Physicians. Motivation and Emotion. 1994;18(4):285-299.

- Hadley J, Mitchell JM, Sulmasy DP, Bloche MG. Perceived Financial Incentives, HMO Market Penetration, and Physicians’ Practice Styles and Satisfaction. Health Services Research. 1999;34(1):307-321.

- Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, McMurray JE, Pathman DE, Williams ES, et al. Managed Care, Time Pressure, and Physician Job Satisfaction: Results from the Physician Worklife Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2000;15(7):441-450.