Michael Karamardian*, Perelman School of Medicine and The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania; Ekta Jagtiani*, University of Pennsylvania; Ankit Chawla*, IESE Business School, and Ingrid M. Nembhard, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

Contact: ingridn@wharton.upenn.edu

Abstract

What is the message? Private equity (PE) ownership in healthcare is largely associated with lower performance on health system aims including patient health outcomes, process quality, and costs for patients and other payers, though notable positive impacts include better cost efficiency for care providers and possibly lower readmissions for patients. Given these results, greater managerial attention is needed to ensure that financial and operational efficiency is not obtained at the expense of other important responsibilities of health systems, which may be possible as some studies indicate that select PE firms perform well across aims, suggesting that management priorities and systems matter.

What is the evidence? We conducted a systematic review of quantitative empirical research on PE’s impact in healthcare published from January 2000-April 2024 in leading health services, business, and economics databases. Our review incorporates a secondary analysis of Borsa et al.’s 2023[1] systematic review (covering 32 articles through April 2023), our primary analysis of articles published subsequently (N=8 from April 2023 to April 2024), and studies forthcoming for presentation at the prestigious AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (N=7; June 2024).

Timeline: Submitted: May 14, 2024; accepted after review May 16, 2024.

Cite as: Michael Karamardian, Ekta Jagtiani, Ankit Chawla, Ingrid M. Nembhard. 2024. An Update on Impacts of Private Equity Ownership in Health Care: Extending A Systematic Review. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.HMPI.org), Volume 9, Issue 2.

* Denotes that authors contributed equally as lead authors of this article

Acknowledgements: We are grateful for the expert assistance of Marcella Barnhart, the Zilberman Family Director of the Lippincott Library of The Wharton School, who performed our databases searches and helped us process the results. Tina Horowitz provided expert administrative and research assistance that saved the day; we are beyond grateful for her and that. We also thank Stephen Sammut, MBA, DBA (Senior Fellow in the Health Care Management Department of The Wharton School and Chair of the Industry Advisory Board of Alta Semper Capital, a private equity impact fund focused on health care investing in Africa), who participated in early conversations about the private equity landscape to help orient us. Kevin Schulman, MD (Professor of Medicine, Clinical Excellence Research Center at the Stanford University School of Medicine and Professor of Operations, Information and Technology at the Stanford Graduate School of Business) provided inspiration and motivation for this work.

Introduction

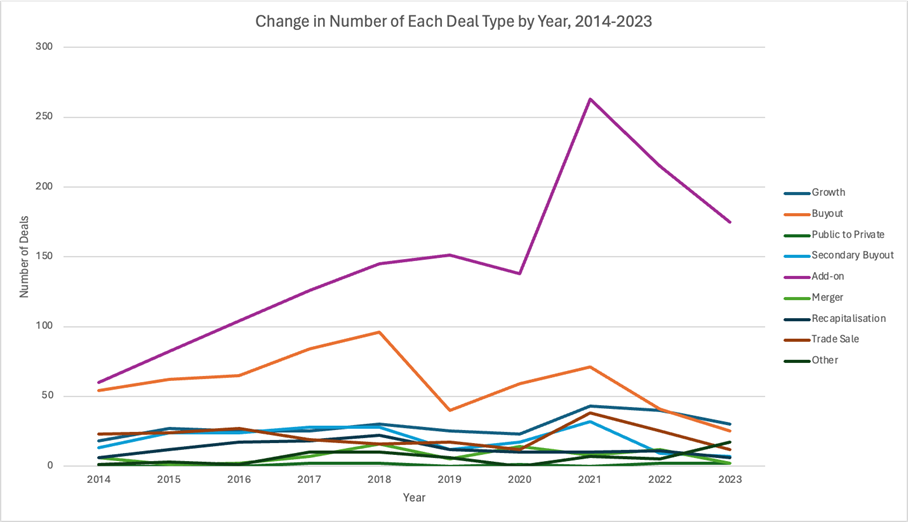

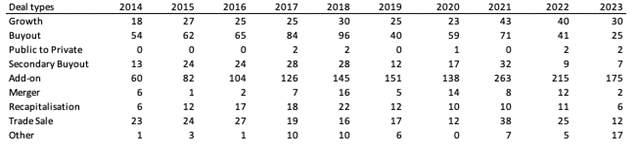

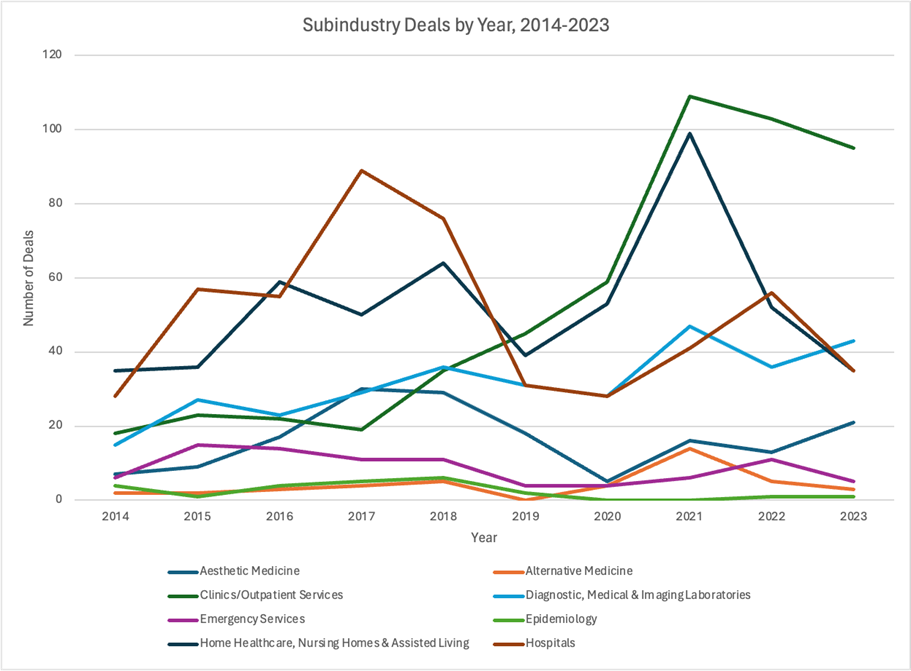

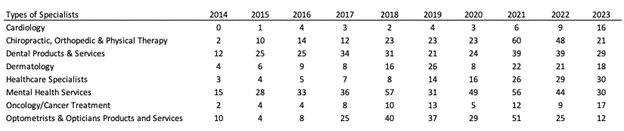

Since 2012, private equity (PE) firms have completed more than 8,000 transactions involving healthcare entities, with an estimated combined value of nearly $1 trillion.[2] Using money from investors, these firms have acquired healthcare services entities (e.g., hospitals, medical groups, nursing homes), whom they then typically charge a management fee and incur sizable debt against. They quickly turn around these organizations, selling them to make profit for their investors, normally within five to 10 years.[3] An estimated 788 PE transactions occurred in 2023 alone just within the healthcare services sector ─ our focal sector in this article ─ making 2023 the third highest year by deal count, even though the count declined relative to recent years. [4]

PE transactions within healthcare services ─ most recently documented in Ma et al.’s [5] article in this issue of HMPI ─ are part of what is labeled the “financialization of health.”[2] This label captures the growing influence of financial incentives, markets, motives, and institutions in the functioning of the healthcare industry.[2] This influence is growing internationally,[1,8] which has sparked the interest of organizational leaders, media, policymakers, clinicians, and researchers who all ponder whether PE investment in healthcare services is good or bad for the industry. [6, 7, 8]

In theory, on the positive side, PE firms may improve the cost and efficiency of healthcare delivery given the inherent financial incentives of their workflow. Because they aim to optimize investment returns, they frequently implement substantial restructuring of acquired entities to generate improvements in these areas.[3, 9] Conceivably, restructuring can also deliver patient care benefits if prioritized as well.[10] However, several reports indicate troubling trends associated with PE ownership including higher bills for patients, outsized growth in earnings for insurers, and high bankruptcy rates, especially in communities that serve a large proportion of low-income and uninsured patients, leading to greater difficulty in accessing care.[7, 11, 12] Over 20% of healthcare entities that filed for bankruptcy in 2023 were owned by PE firms,[13, 14] prompting concern that PE ownership may leave communities depleted of healthcare. This concern has intensified as PE-backed Steward Health Care, the largest physician-led hospital operator in the United States (U.S., with 30 hospitals), filed for bankruptcy in May 2024, unable to pay its $750 million debt.[15, 16] Steward, formerly renowned for its outstanding performance in the value-based Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP),[17] had served as a compelling example of the positive influence of PE. After PE acquisition, Steward transformed into one of the major for-profit U.S. hospital systems, expanding healthcare nationally. Then, under pressure to achieve financial profit, Steward underwent substantial operational restructuring, primarily emphasizing cost reduction and division optimization, but remained unable to repay its sizable PE-linked debt. See related article by Kumar in this issue of HMPI.

The recent events and growth of PE have prompted many commentaries, conferences, and case studies on PE’s impact in healthcare.[18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26] Recently, they also spurred a systematic review of all related empirical research published from 2000 to 2023. That review by Borsa et al.[a][1]aimed to provide an evidence-based summary of the impact of PE ownership with respect to health outcomes, costs to patients or payers, cost to operators, and quality. In sum, Borsa et al. found that PE ownership is “often associated with harmful impacts on costs to patients or payers and mixed to harmful impacts on quality” (p. 1). This largely negative conclusion has been affirmation for some within the healthcare community. Others wonder whether the conclusions would stand with additional data and finer-grained analysis of study outcome variables.

To answer these open questions, we conducted a systematic review with three aims: 1) to include data from the year since Borsa et al. (April 2023-April 2024) to assess if the patterns identified by them persist; 2) to assess the influence of PE on patient health outcomes and care quality as a single category, distinct from process quality enablers (a departure from Borsa et al. that we explain in Methods below); and 3) to investigate whether the effects of PE ownership differ by PE firm. Our analysis updates the existing systematic review of the evidence of PE’s impact and adds nuance through subset analyses of data. It thus is both a replication and expansion to contribute to a detailed and current evidence base on a key topic in healthcare management today, enabling knowledge to guide policy and practice.

Methods

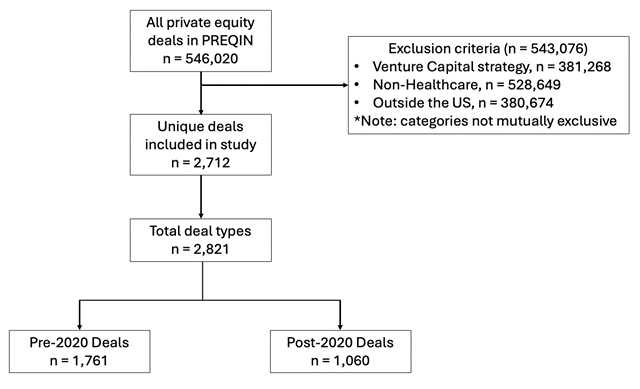

Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

Given our aims of providing a detailed and updated systematic review of empirical research on PE, our review consisted of three components. In the first component, we abided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement[27] and used our search procedures to bring Borsa et al.’s review forward in time. Specifically, with the assistance of our university librarian, we searched for English-language articles in PubMed (MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process), Scopus, and Web of Science for the full year following Borsa et al.’s, that is, from April 16, 2023 (the final date of their search) to April 15, 2024. In PubMed, a search was conducted for “private equity”. For Scopus and Web of Science, the search strategy included various bibliographic fields (title, abstract, and author keywords in Web of Science; and title, abstract, and keywords in Scopus) using the terms health* or hospital* or physician* or doctor* or medical or nursing or hospice or ambulatory or “long term care” and “private equity.”

To limit the possibility that we missed relevant research published by business or economics scholars, we added search of Business Source Complete, ABI/Inform and EconLit. As these sources were not included in the Borsa et al. article, we expanded the search of these to begin in 2000 to align with Borsa et al., agreeing that PE acquisitions before that time were likely to be less relevant to current events. Our search terms were the same as for Web of Science. Identified articles were reviewed by our librarian to assess whether they met our three inclusion criteria: (1) studied any form of PE ownership, (2) utilized empirical, quantitative data, and (3) assessed the impact of PE ownership in a healthcare delivery setting using statistical analyses. Our librarian uploaded articles that met criteria to a shared Box for our full review and data extraction. She also uploaded Excel files with the list of all articles from each database that documented reasons for exclusion/inclusion and provided a link to the article. Excluded articles focused on non-healthcare related effects, did not include statistical analyses, analyzed predictors of PE ownership, or were commentary/editorial or news pieces.

The second component of our review aimed to capture studies forthcoming in publications in an effort to be as current as possible. To identify these, we conducted an online search of the 2024 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (ARM) program.[28] AcademyHealth is the premier professional association for health services researchers, policymakers, and healthcare practitioners and stakeholders in the U.S. Selection for presentation during its research meeting occurs through blind, committee review of abstracts, with selection for podium presentation limited to research assessed as most rigorous and impactful. We searched the 2024 program using “private equity” and applied the same eligibility criteria used in the first component of our search methods.

The third and final component of our review consisted of revisiting the 32 articles identified by Borsa et al. as evaluating the impacts of PE ownership on at least one category of health outcomes, costs to patients or payers, cost to operators, or quality, or a combination of these factors. We revisited these articles to ensure that our categorization of impacts for new research aligned with theirs in order to create continuity as the field of study and analysis grows.

Data Extraction and Analysis

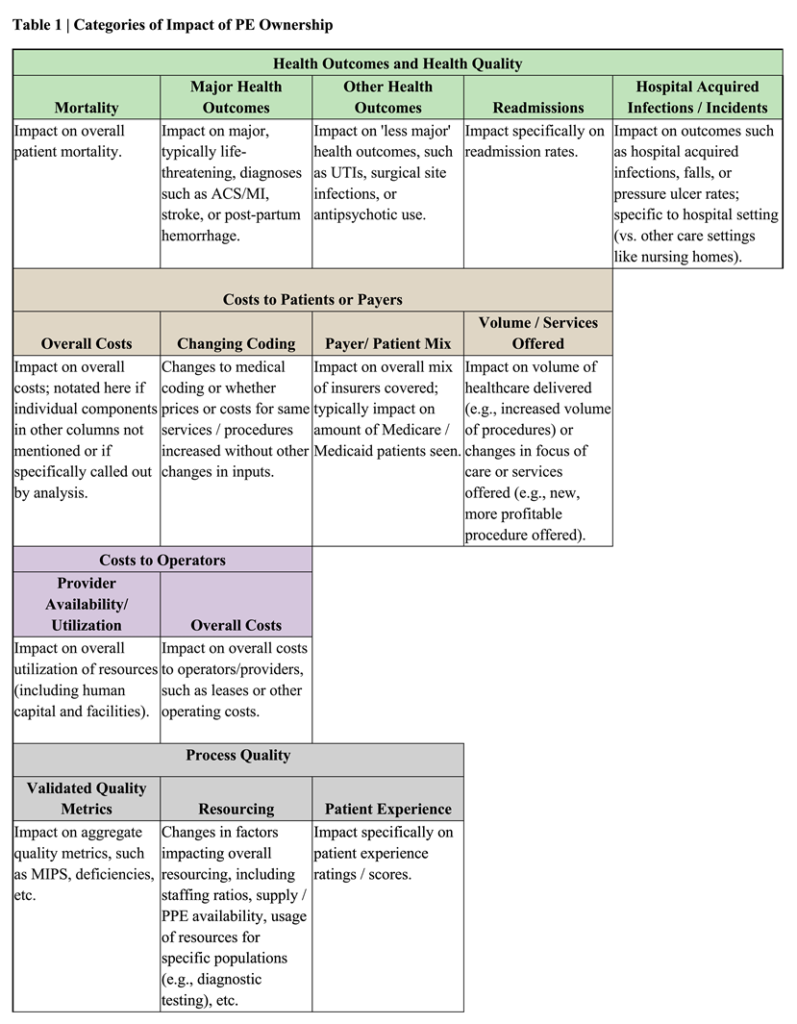

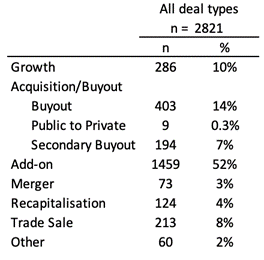

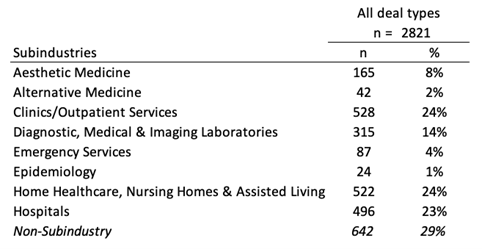

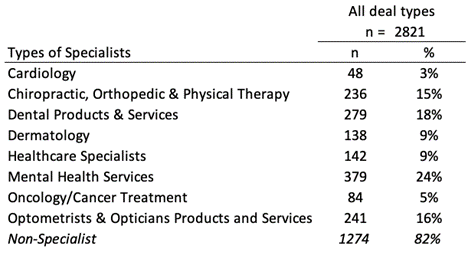

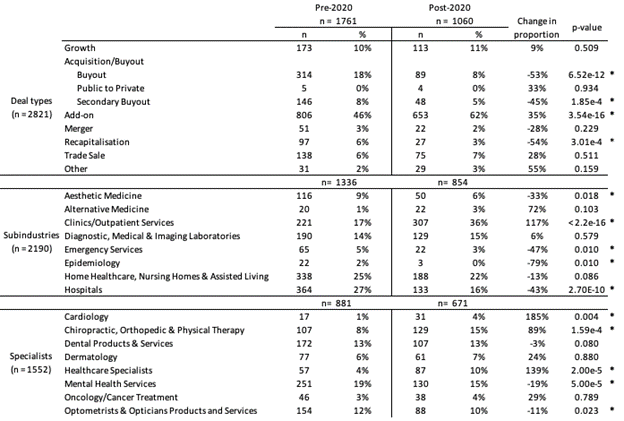

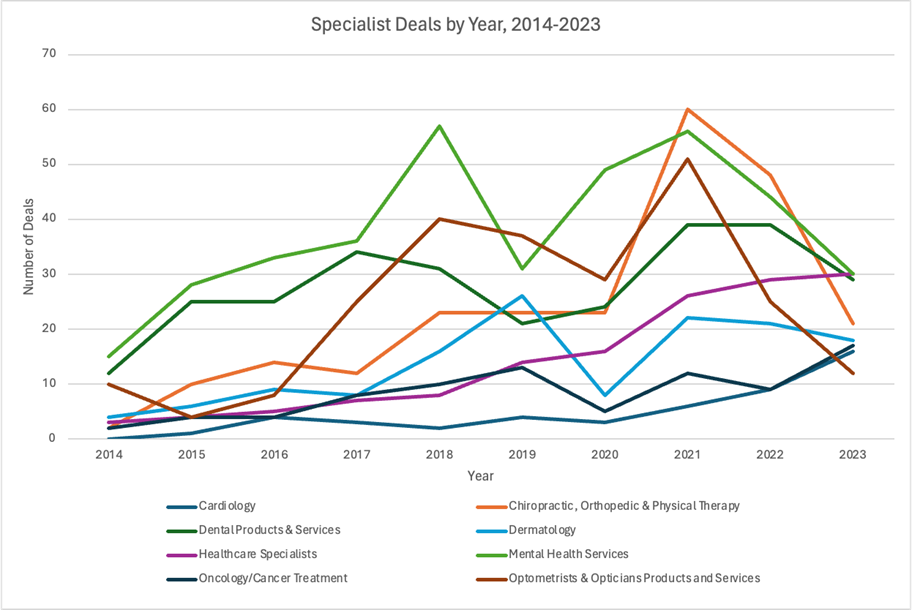

Our data analysis and extraction had two phases. In the first phase, we focused on establishing the categories of impact that would be the focus of our review. We used Borsa et al.’s categories (health outcomes, costs to patients or payers, cost to operators, and quality) as our starting point and also allowed our “fresh eyes” to consider whether additional or more fine-grained categories would be valuable additions to present. With this objective, one team member (EJ) documented the results in detail from 20 articles in our dataset (the first 12 in Borsa et al. and the first 8 published since then) and noted themes across them, all in an Excel file. Next, two additional members of the team (MK and AC), both with clinical and business training, reviewed the Excel file independently and then jointly to create the list of categories of impact to be used for the analysis of all articles. All authors met to finalize the categories, which are presented in Table 1.

A notable distinction between our categories of impact and those contained in Borsa et al.’s is that we chose to differentiate within the category of Quality, drawing upon Donabedian’s[29, 30] taxonomy. Specifically, we distinguished between impacts related to patient health (often regarded as technical quality of care and labeled here as “Health Outcomes and Health Quality”) and impacts related to enablers of care delivery (often regarded as process and labeled here as “Process Quality”). We see value in distinguishing these impacts because, although process and outcomes measures are often loosely-coupled, systems that affect them and interventions to improve them can differ. Our differentiation led to reclassification of some measures from Quality in Borsa et al. (i.e., surgical site infections and (in)appropriate antipsychotic use) to Health Outcomes and Quality here. That resulted in more specificity as the broad category of Quality became more precisely Process Quality enablers. Within the Process Quality and Health Outcomes and Quality categories, we took the added step of documenting sub-categories to add another level of precision to our main results presentation. Similar content is captured in Borsa et al.’s supplement.

Once we finalized our categories of impact as noted in Table 1, we divided the articles/abstracts identified from our three (search) components among our three lead authors for data extraction. Each article/abstract was reviewed by at least two team members to ensure accuracy and consistency in categorization. Reviewers for each article extracted the following study information: author, year of publication, article title, research question/objective, country, healthcare setting, sample, study design, time period of analysis, sample size, named PE firm (if applicable), impact(s) assessed, significance of impact based on p-value < 0.05 as significant, and indicator for whether a category changed from Borsa et al. Information was recorded in Excel spreadsheets. The full authorship team then met on four occasions to review the data to identify patterns and answer the research questions.

Results

One-Year Growth in Research (2023-2024)

Our three search strategies yielded 47 articles/abstracts for analysis, 15 of which were additions to the 32 articles previously identified by Borsa, for a research growth rate of 47 percent in just one year for studies meeting our inclusion criteria. Of the 15 new articles, eight were identified from among 57 new articles retrieved through our database search of articles since Borsa et al. and seven were identified through search of the AcademyHealth program, which contained 14 studies. These additions from AcademyHealth were largely by research teams (5 out of 7) with a track record of publishing empirical research on PE, adding credibility to our inclusion of their forthcoming work. Excluded articles obtained from both searches had failed to meet our inclusion criteria. Of note, no new articles were identified in our added databases; either nothing new had been published or articles were already included in Borsa et al., demonstrating the completeness of their 2023 search.

Impact of PE in Healthcare

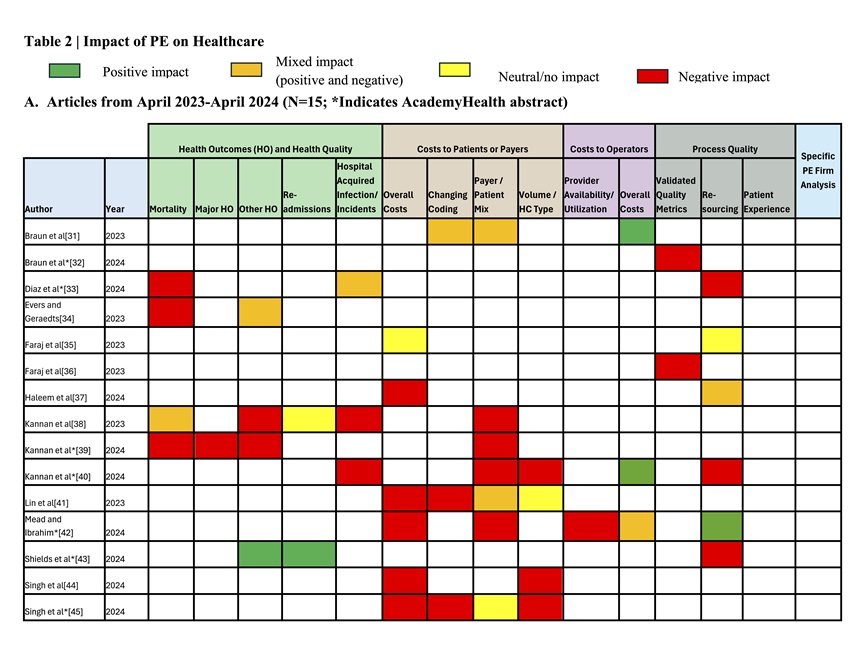

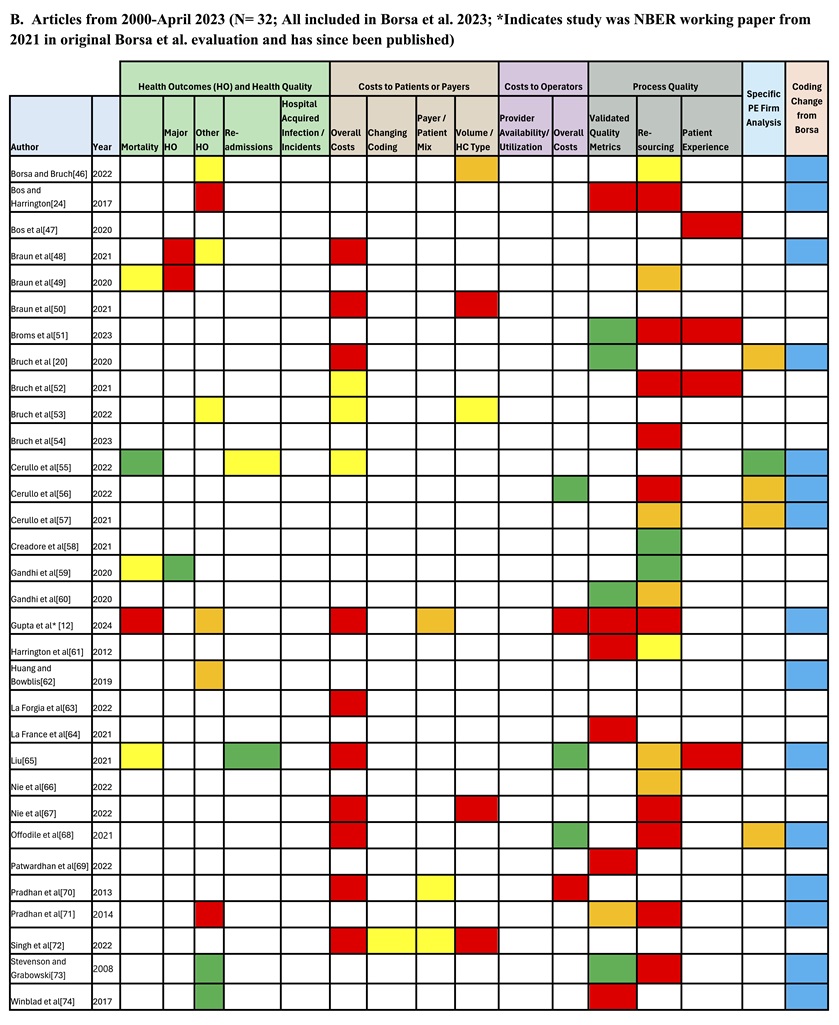

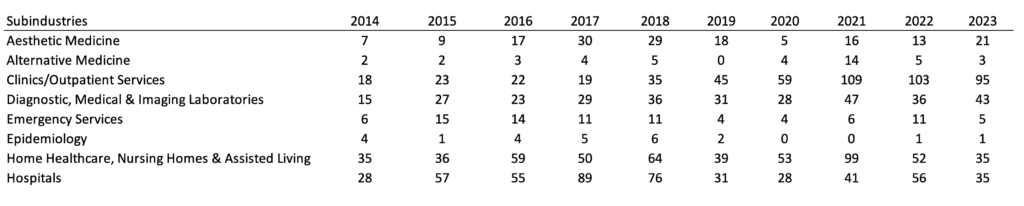

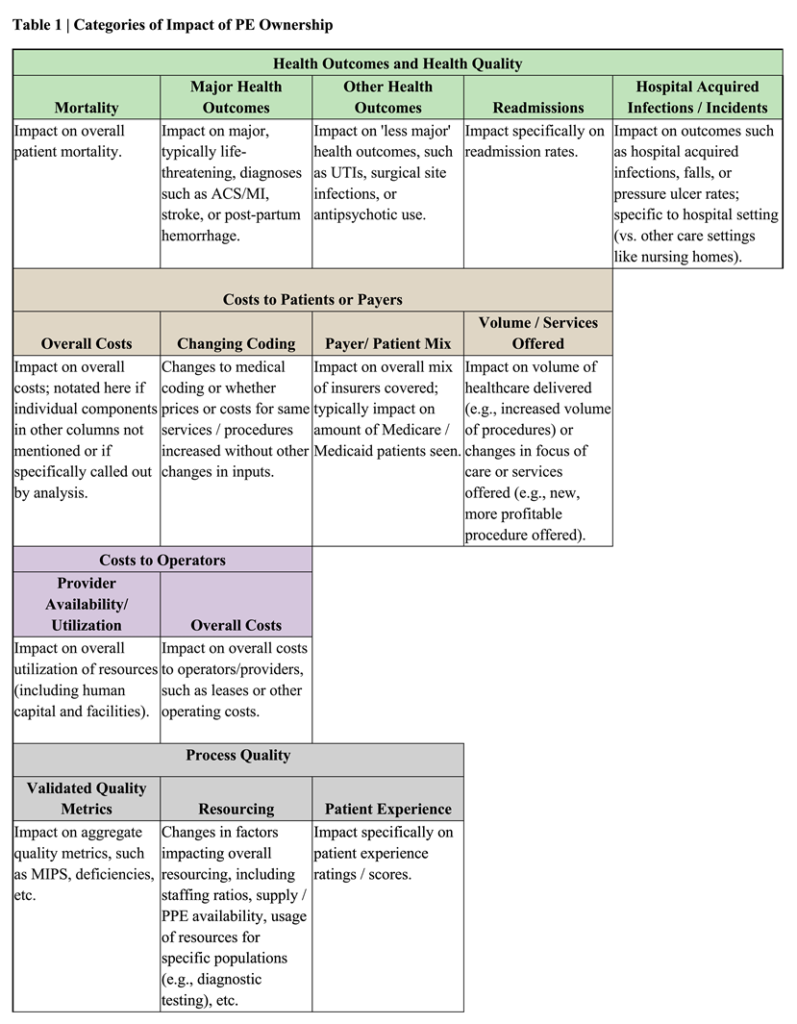

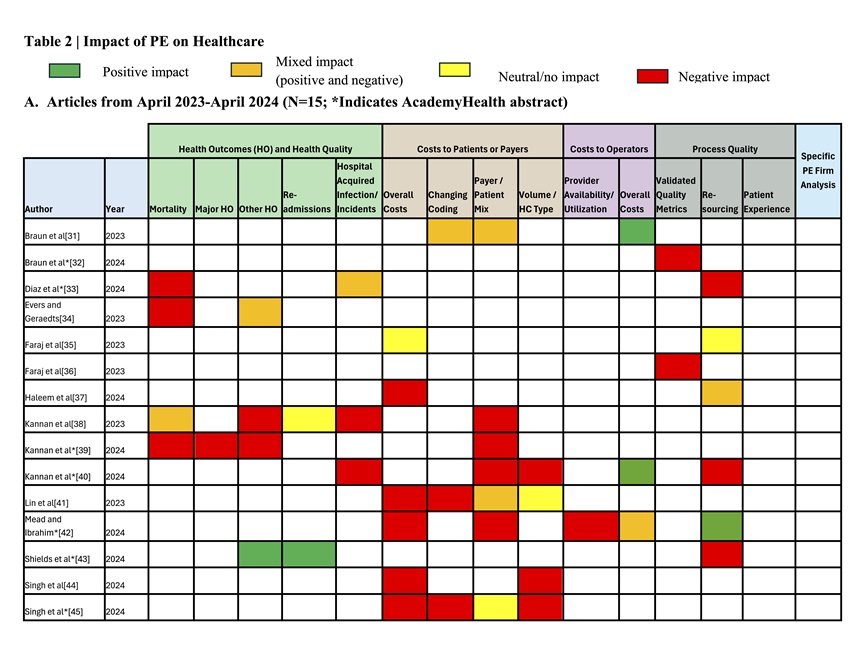

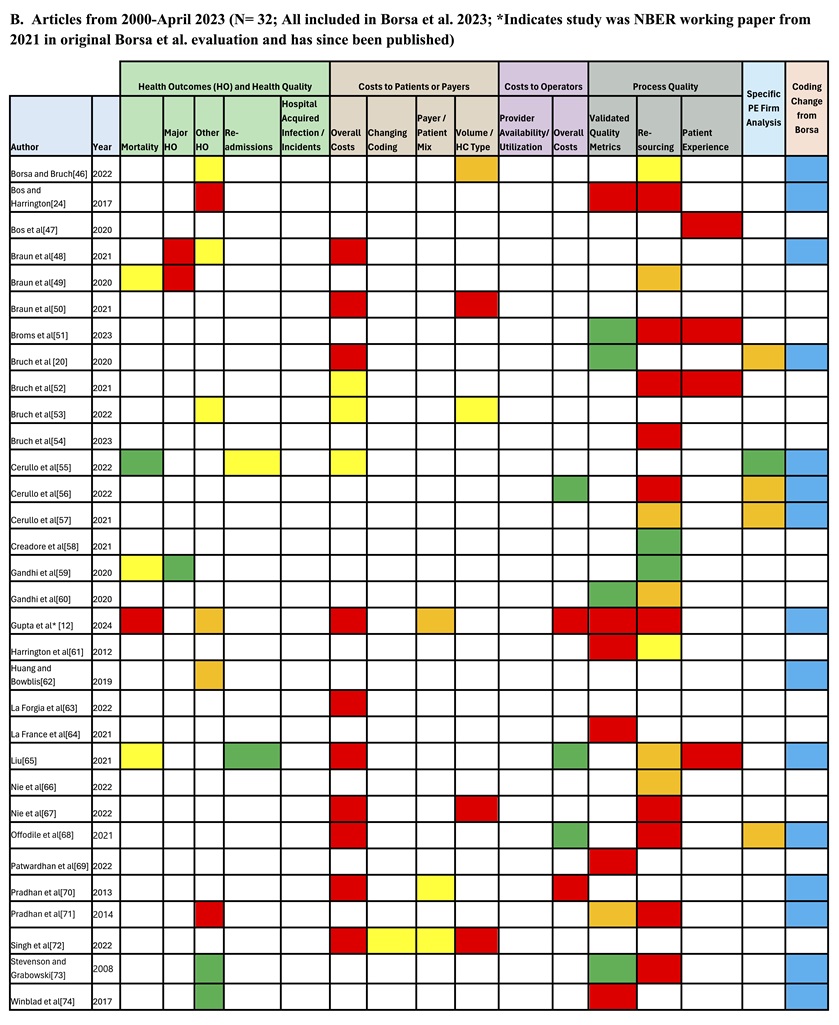

Table 2 shows the impacts reported across the 47 articles/abstracts published from 2000-April 15, 2024. Part A shows the results for the research published in the most recent year, whereas Part B shows the results for articles contained in Borsa et al. and whether a classification change had occurred based on categories in Table 1. These tables also indicate the five studies that assessed whether results varied by PE firm, comparing HCA-ownership relative to other owners.

Health Outcomes and Quality

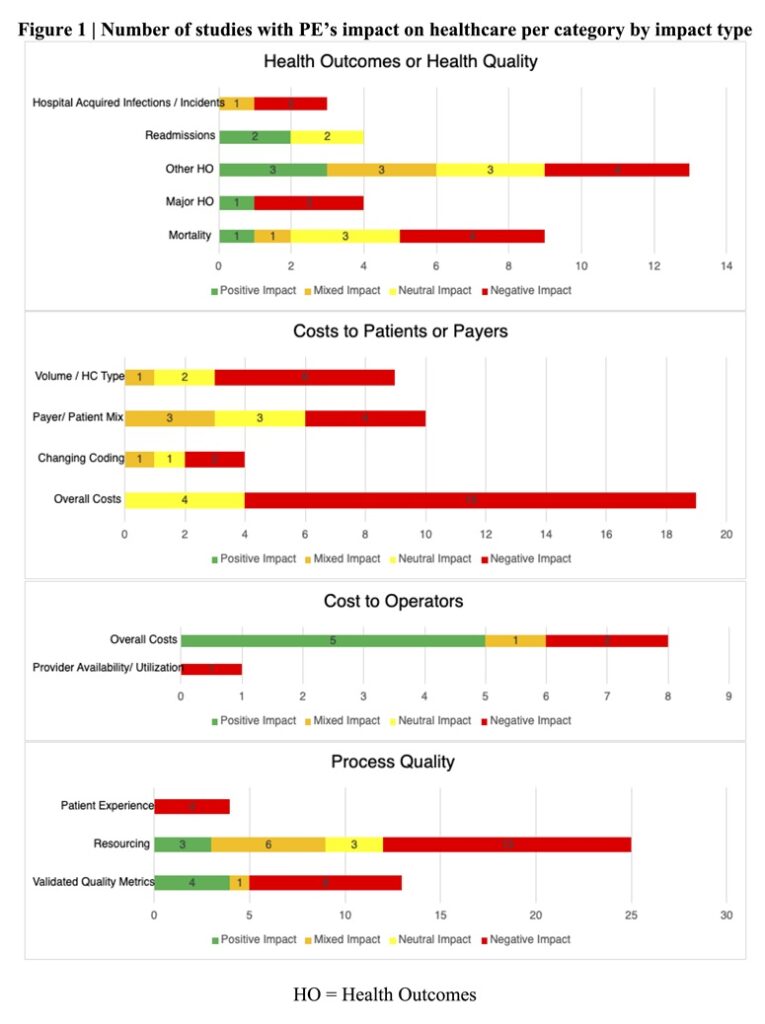

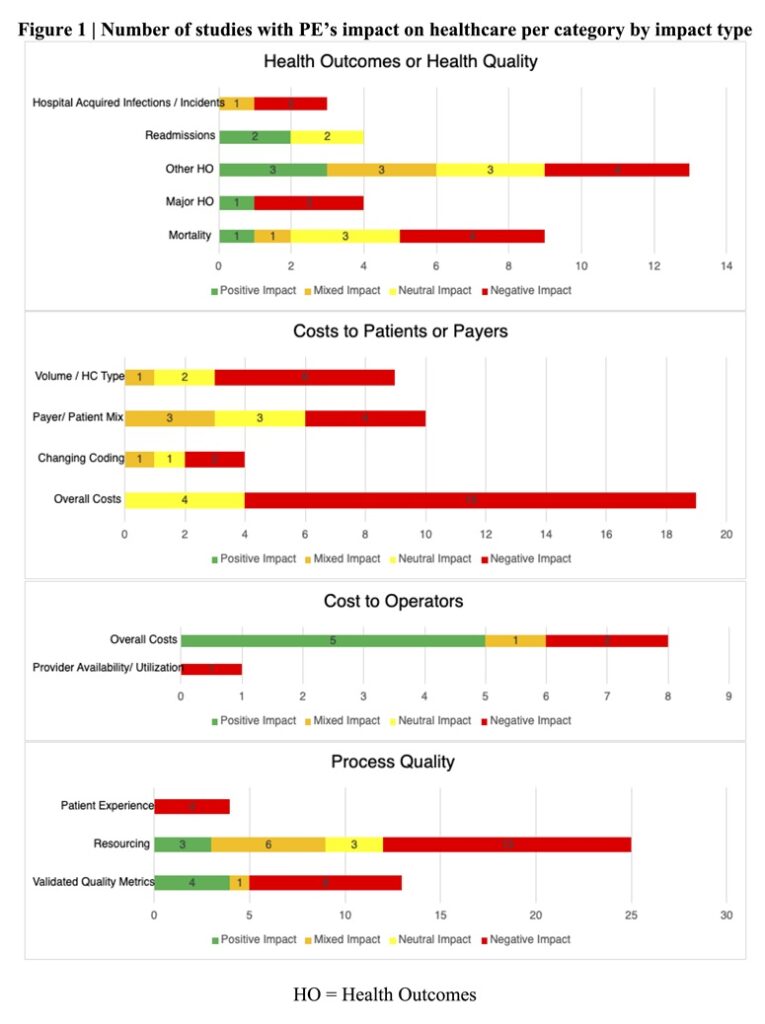

Within this category, the majority of effects assessed in studies during the last year indicate unfavorable health consequences for patients. Specifically, studies indicate that patients served by PE-owned entities have higher rates of mortality, major and other adverse health outcomes, and complications such as hospital acquired infections. The most recent year’s data reinforces the negative view of PE’s impact on health outcomes overall, as there were relatively few articles citing positive impact, and they often indicated negative impacts as well. Just one study in the past year indicated uniformly better health outcomes, with the patients in that study having lower readmission rates and better other health outcomes (e.g., improved rates of urinary tract infections).[43] Moreover, as Part B of Table 2 shows, we observe more studies reporting negative and neutral impacts compared to Borsa et al. in this category due to our decision to include health quality impacts in this category, which shifted some studies into this category. Thus, across the entire time frame for review, the data suggests that PE ownership is associated primarily with negative impacts on patient health outcomes and health quality, although there are studies indicating positive and/or neutral effects.[43, 57, 60, 73, 74] This is seen in both Table 2 and Figure 1, which presents the number of studies that report each type of impact (positive, mixed, neutral, or negative) within each category.

Cost to Patients and Payers

Studies to date overwhelmingly indicate that PE ownership is also associated with higher costs to patients and payers. Across time periods and all sub-categories assessed (overall costs, billing codes (e.g., changing to higher paying codes), payer/patient mix (e.g., shifting away from costly patients), and volume of more expensive services offered/provided), the preponderance of evidence indicates negative financial effects for these two groups, with a recurring pattern of higher expenses for payers and patients linked to service fee growth after a PE acquisition.[41, 63, 68] Studies also suggest that financial access to care is hindered as changes to payer/patient mix occur that typically involve reduced percentages of Medicare, Medicaid, or Dual-Eligible patients being covered, [38, 39, 42],, a pattern highlighted in the most recent year of studies, although evidence is mixed. To the extent studies indicated positive effect on costs for these two groups, they also included negative effects. Thus, overall, the most recent year of results is consistent with the results of Borsa et al., with the most recent studies expanding the field by offering mechanisms for the overall cost growth indicated by the 2000-2023 articles. Notably, increased costs were not often accompanied by better Health Outcomes or Health Quality; only one [65] of three studies that examined this possibility [12, 48, 65] indicated such betterment.

Costs to Operators

Studies in this category indicate a mix of positive and negative effects on cost for operators (i.e., operational expenses). That said, this is the only category with significant evidence of positive impact, relative to the number of studies. While several studies indicate cost reductions resulting from greater efficiencies,[31, 40, 55, 65, 68] there was counterevidence that in some cases PE ownership actually raised costs such as lease costs,[12] which may not be directly linked to improved service delivery or patient care. Additionally, one of the studies in the past year, the first to consider how provider availability or utilization is impacted, found a negative effect, i.e., lower utilization that increased cost for operators.[42]

Process Quality

Overall, process quality had largely mixed impact, though notably many studies reported significantly decreased staffing levels at PE-owned facilities.[12, 24, 40, 43, 51, 52, 55, 68, 71, 73] The sub-component within process quality where analysis shows that PE firms perform most positively is in their impact on Validated Quality Metrics.[20, 51, 59, 73 ] Notably, no studies reported any positive impacts on patient experience scores.

The Effect of PE Firm

Five articles contained a sub-analysis to parse the effect that PE acquisition of HCA-associated hospitals had on various impact metrics. All of these articles were included in the Borsa et al. review but had not been examined separately to assess whether specific PE firm management moderated the impact of ownership. Notably, HCA’s impact on health outcomes, though only analyzed in one study, [55] was significant on the important metrics of 30-day patient mortality and mortality from myocardial infarction (heart attack). While impacts on costs and process quality were mixed,[20, 56, 57, 68] the significant and positive findings provide evidence of potential variance in impact due to specific PE firm ownership. We observed no systematic differences in impacts based on healthcare setting or specialty.

Discussion

The primary purpose of our review was to provide the most up-to-date summary of research on PE’s impact on healthcare delivery settings. In multiple venues, we had heard or read debate about whether PE is good or bad for healthcare – for patients, the workforce, organizations, and ultimately the system. Borsa et al. had admirably conducted an extensive systematic review of the literature from 2000 to 2023. It left a negative impression of PE ownership and raised the question of whether newer, additional studies would provide results that offer a more mixed or favorable impression. Our review, which adds a year of studies to Borsa et al.’s and reports on more sub-categories of impacts as part of the main analyses, reinforces Borsa et al.’s findings. This is true whether just the 15 new studies are considered or the entire set of 47 studies.

Our review confirms negative associations across three of the four categories of impacts identified: health outcomes and health quality, cost to patients and payers, and process quality enablers. The negative associations appeared stronger in the category of health outcomes and health quality once we shifted adverse event quality measures to be alongside health outcomes. The one categorical exception to negative-dominant impacts occurs for cost to operators, which had the most evidence of positive effects. Gains in this area indicate that PE ownership is delivering on this expectation. A modus operandi of PE is to increase operational efficiency and reduce costs so the acquired is sellable at a profit for original investors.[2, 3, 7],

The results of this review add to concern about the growth of PE in healthcare. They imply that this form of financialization in healthcare can bring cost efficiency for the acquired operator but also significant detrimental effects for patients on multiple dimensions, some of which may result from declines in organizations’ process quality, as processes influence outcomes in many instances, meaning they too deserve attention.[29,30] Given the negative findings for process quality and outcomes, it is not surprising that no study showed improved patient experience scores after PE acquisition. Lack of improvement and negative effects may have several potential reasons, ranging from PE’s inherent focus on short-term profitability and thus cost-cutting actions to less tangible causes like disruptions to organizational culture due to restructuring and operational ‘optimizations’, which can undermine service delivery.[

Our findings, however, are not wholly damming of PE. At least two sets of findings suggest that PE can have beneficial effects. The first are the subset analyses of HCA versus non-HCA PE-owned hospitals, which showed significantly better 30-day patient mortality rates and mortality from myocardial infarction (heart attack) for the HCA hospitals.[55] The second indicator is the many mixed results studies (orange boxes in Table 2) alongside the few positive impact studies (green boxes) such as for readmission rates.[43, 65] While the number of these studies is far fewer than the negative studies, as evident in Figure 1, their existence is noteworthy. They imply positive possibility and that more research is needed that examines under what conditions PE is helpful. The HCA studies, in particular, beg the question: What exactly do PE firms that perform well in areas beyond own-cost management do? We know that firms operate differently and management matters in healthcare.[75] It may be time to study how different PE firms in healthcare manage differently, the implications of those choices, and what shifts in operational and managerial strategy are possible to allow PE-owned entities to not only deliver efficiency but also other health system aims, assuming that investors are willing to accept this challenge. Study of over 15,000 firms across industries found that PE firms are better managed than government, family, and privately owned firms, and have similar management to publicly listed firms, in the developed and developing world. They tend to have strong people management (hiring, firing, pay, and promotions) and monitoring management practices (lean manufacturing, continuous improvement, and monitoring).[76] Therefore, it may be that there is lurking potential in PE firms for healthcare. Current negative impacts may be the result of the PE model itself or insufficient experience with or adaptation of this innovation to the current era of healthcare. Innovation and organizational learning research both indicate that negative results are common early in the use of new innovations; time is often needed to learn appropriate strategies for the setting.[77, 78] Though PE investment in healthcare services has been occurring for decades and the recent volume of transactions appears motivated by the same uncertainty, goals, and motivations of past private investment in healthcare,[7] the current era differs in ways (e.g., more burned out workforce, players, technology-enabled activities, and reserves for capitated business amid expectations for transparency and value-based care) that may present novel contexts for PE operators. Thus, additional study of specific PE-firm behavior is needed to get us closer to understanding the variation in impacts observed across studies.

Our study’s (re)classification of specific measures into separate categories of quality, specifically ‘process’ and ‘health outcomes’ quality, and examination of the sub-categories within them allows for nuanced understanding of effects. While completely reasonable to group all under “quality,” the two levels of categorization allowed us to observe the distinct association of PE ownership with patient health (for example, we felt patient mortality effects deserve to be highlighted) and observe the association across the spectrum from the most serious (e.g., mortality) to minor health effects. It also allowed us to appreciate the distinction of effects on process quality enablers (e.g., resources), which can affect patient health but also have separate effects (e.g., affecting staff retention rates) that may not impact patient health. The categories presented in Table 1 may be used to guide future studies and serve as a starter checklist for PE performance.

While we endeavored to capture all published research and forthcoming articles since Borsa et al., it is possible that studies were missed despite our broad search for “private equity,” search of databases across scholarly fields, and search within the program for the most prominent health services research conference. Another potential limitation of this work is that its conclusions are based on studies that vary in their rigor and bias. We did not document these threats for the new articles. Borsa et al. had already documented such variation for the studies included in their analysis. Although we observed that several of the new articles used more robust study designs (e.g., allowing for difference-in-differences analyses), across the dataset, the threats to our findings remain. Several studies did not account for confounders that may impact the results, such as pre-acquisition financial health, market conditions, and regulatory modifications. This hinders attribution of identified impacts to PE ownership. Additionally, the included studies exhibit substantial heterogeneity in scope, setting, and measurement. This has the advantage of allowing assessment of generalizable patterns but also means that setting-specific effects (positive or negative) are obscured, especially given the few studies in any context. Given the growth in studies in one year, however, we are optimistic that the research on PE will continue to grow such that robust conclusions about the impact of PE in healthcare generally and with nuance will be gained.

The increase in empirical study following Borsa et al.’s work suggests an ongoing need for comprehending the influence of PE on healthcare. Research to date shows that PE ownership can deliver the cost efficiency gains promised but also that positive impacts on patient health outcomes, process quality, and cost to patients and payers do not naturally accompany these gains. Rather, much of existing evidence indicates negative impacts in these areas. There is also some indication, however, that management can matter. The positive health impacts found for readmission rates and in HCA-hospital sub-analyses suggest the possibility for PE ownership to deliver on cost and quality aims for patients and organizations. This likely depends on organizational priorities and management systems implemented.

References

[1] Borsa A, Bejarano G, Ellen M, Bruch J D. Evaluating trends in private equity ownership and impacts on health outcomes, costs, and quality: systematic review BMJ 2023; 382:e075244 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075244

[2] Bruch JD, Roy V, Grogan CM. The financialization of health in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2024 Jan 11;390(2):178-182. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2308188. PMID: 38197821

[3] Cutler DM, Song Z. The new role of private investment in health care delivery. JAMA Health Forum. 2024;5(2):e240164. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2024.0164

[4] Olsen, E. Healthcare PE deals third-highest on record in 2023: Pitchbook. Healthcare Dive. Feb. 12, 2024. https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/healthcare-private-equity-deals-2023-pitchbook/707245/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=rasa_io&utm_campaign=newsletter

[5] Ma LW, Buckmann C, Shah SA, Schulman KA. Healthcare Private Equity: A Review of Key Case Studies and Recommendations for Effective, Equitable Private Investment in Healthcare. Health Management, Policy and Innovation (www.HMPI.org). 2024. Volume 9, Issue 2.

[6] Scheffler RM, Alexander L, Fulton BD, Arnold DR, Abdelhadi OA. Monetizing medicine: private equity and competition in physician practice markets. American Antitrust Institute. 2023 Jul 10.

[7] Pauly MV, Burns LR; Equity Investment in Physician Practices: What’s All This Brouhaha?. Journal of Health Politics Policy Law 2024; 11186103. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-11186103

[8] Andersen JL. Impact Of Private Capital And Financialization On Health Equity: A Response To Enekwechi. Health Affairs Forefront. 2024.

[9] Appelbaum E, Batt R. Private Equity Buyouts in Healthcare: Who Wins, Who Loses? Institute for New Economic Thinking Working Paper Series. Published online 2020:1-115. https://doi.org/10.36687/INETWP118

[10] Enekwechi A. Private Capital Is A Key Component To Improving Health Equity. Health Affairs Forefront. 2023.

[11] Hamby, C. Health Insurers’ Lucrative, Little-Known Alliance: 5 Takeaways. The New York Times (April 7, 2024).

[12] Gupta A, Howell ST, Yannelis C, Gupta A. Does private equity investment in healthcare benefit patients? Evidence from nursing homes. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021. doi:10.3386/w28474.

[13] Private Equity Stakeholder Report. (2024). Private Equity Healthcare Bankruptcies are on the Rise. Accessed May 7, 2024: https://pestakeholder.org/private-equity-healthcare-bankruptcies-are-on-the-rise/

[14] Bankruptcies Jump At Private Equity-Owned Healthcare Companies. (n.d.). Accessed May 1, 2024. https://www.medcentral.com/biz-policy/bankruptcies-jump-among-private-equity-owned-healthcare-companies

[15] Steward health care finalizing financing deal with medical properties trust to support its restructuring. Press Release May 6, 2024. https://www.steward.org/newsroom/2024-05-06/steward-health-care-finalizing-financing-deal-medical

[16] Vogel, S. Steward Health Care files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Healthcare Dive (May 6, 2024) https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/steward-health-care-files-chapter-11-bankruptcy/714050/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=rasa_io&utm_campaign=newsletter

[17] Medicare shared savings program. Steward.org. Accessed May 7, 2024. https://www.steward.org/domain-specific/720191/MedicareACO/MSSP

[18] Patouillard E, Goodman CA, Hanson KG, Mills AJ. Can working with the private for-profit sector improve utilization of quality health services by the poor? A systematic review of the literature. International Journal for Equity and Health. 2007;6(1). doi:10.1186/1475-9276-6-17

[19] Beyer KM, Demyan L, Weiss MJ. Private equity and its increasing role in US healthcare. Advances in Surgery. 2022;56(1):79-87. doi:10.1016/j.yasu.2022.02.003

[20] Bruch JD, Gondi S, Song Z. Changes in hospital income, use, and quality associated with private equity acquisition. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020;180(11):1428-1435. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3552

[21] Ivashina V, Lerner J. Pay now or pay later?: The economics within the private equity partnership. Journal of Financial Economics. Published online 2016. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2757039

[22] Scheffler RM. Soaring Private Equiry Investment in the Healthcare Sector: Consolidation Accelerated, Competition Undermined, and Patients at Risk.; 2021.

[23] Powers BW, Shrank WH, Navathe AS. Private equity and health care delivery: Value-based payment as a guardrail? JAMA. 2021;326(10):907. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.13197

[24] Bos A, Harrington C. What happens to a nursing home chain when private equity takes over? A longitudinal case study. Inquiry. 2017;54:004695801774276. doi:10.1177/0046958017742761

[25] Gondi S, Song Z. Potential implications of private equity investments in health care delivery. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1047. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.1077

[26] Hunter BM, Murray SF. Deconstructing the financialization of healthcare. Development and Change. 2019;50(5):1263-1287. doi:10.1111/dech.12517

[27] Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

[28] AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (ARM) program 2024. Baltimore, MD; June 2024.

[29] Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988 Sep 23-30;260(12):1743-8.

[30] Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83(4):691-729.

[31]Braun RT, Unruh MA, Stevenson DG, et al. Changes in diagnoses and site of care for patients receiving hospice care from agencies acquired by private equity firms and publicly traded companies. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6(9):e2334582. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.34582

[32] Braun RT, Soltoff, A, Unruh, M, Stevenson, D, Casalino, L. Associations between Private Equity Firms’ and Publicly Traded Companies’ Ownership of Hospice and Caregiver Assessments of Hospice Quality. Unpubished paper. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (Baltimore, MD, June 2024).

[33] Diaz, A, Rohde, S, Kunnath, N, Dimick, J, Ibrahim, A. Association of private equity acquisition with inpatient general surgery outcomes. Unpublished paper. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (Baltimore, MD, June 2024).

[34] Evers J, Geraedts M. COVID-19 risks in private equity nursing homes in Hesse, Germany – a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatrics. 2023;23(1):648. doi:10.1186/s12877-023-04361-8

[35] Faraj KS, Kaufman SR, Herrel LA, et al. The immediate effects of private equity acquisition of urology practices on the management of newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Cancer Medicine. 2023;12(24):22325-22332. doi:10.1002/cam4.6788

[36] Faraj KS, Kaufman SR, Herrel LA, et al. Acquisition of urology practices by private equity firms and performance in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System. Urology Practice. 2023;10(6):597-603. doi:10.1097/UPJ.0000000000000441

[37] Haleem A, Garcia A, Khan S, Shakelly P, Lee DJ. Access to sudden sensorineural hearing loss care at private equity‐owned otolaryngology clinics. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. Published online 2024. doi:10.1002/ohn.665

[38] Kannan S, Bruch JD, Song Z. Changes in hospital adverse events and patient outcomes associated with private equity acquisition. JAMA. 2023;330(24):2365-2375. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.23147

[39] Kannan S, Stevens, J, Bruch, J, Song, Z. Hospital staffing, bed use, and patient outcomes after private equity acquisition. Unpublished paper. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (Baltimore, MD, June 2024). AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (Baltimore, MD, June 2024

[40] Kannan, S., Stevens, J, Song, Z. Hospital Staffing and Related Outcomes after Private Equity Acquisition. Unpublished paper. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (Baltimore, MD, June 2024)

[41] Lin H, Munnich EL, Richards MR, Whaley CM, Zhao X. Private equity and healthcare firm behavior: Evidence from ambulatory surgery centers. Journal of Health Economics. 2023;91:102801. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2023.102801

[42] Mead, M, Ibrahim, A. Private equity acquisitions of hospitals and changes in utilization and financial performance. Unpublished paper. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (Baltimore, MD, June 2024).

[43] Shields, M, Yang, Y, Busch, S. Psychiatric hospitals are not immune to financialization: Private equity trends and its association with staffing and quality performance. Unpublished paper. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (Baltimore, MD, June 2024).

[44] Singh Y, Aderman CM, Song Z, Polsky D, Zhu JM. Increases in Medicare spending and use after private equity acquisition of retina practices. Ophthalmology. Published online 2023. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.07.031

[45] Singh, Y, Song, Z , Polsky, D, Zhu, J. Increases in physician professional fees in private equity owned vs health system-affiliated gastroenterology practices. Unpublished paper. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting (Baltimore, MD, June 2024).

[46] Borsa A, Bruch JD. Prevalence and performance of private equity-affiliated fertility practices in the United States. Fertility and Sterility. 2022;117:124-30. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.035

[47] Bos A, Kruse FM, Jeurissen PPT. For-profit nursing homes in the Netherlands: What factors explain their rise? International Journal of Health Services. 2020;50:431-43. doi:10.1177/0020731420915658

[48] Braun RT, Jung HY, Casalino LP, Myslinski Z, Unruh MA. Association of private equity investment in US nursing homes with the quality and cost of care for long-stay residents. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(11):e213817. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.3817

[49] Braun RT, Yun H, Casalino LP, et al. Comparative performance of private equity-owned US nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3:e2026702. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26702

[50]Braun, RT, Bond AM, Qian Y, Zhang M, Casalino LP. Private equity in dermatology: Effect on price, utilization, and spending: Study examines the prevalence of private equity acquisitions and their impact on dermatology prices, spending, use, and volume of patients. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2021;40(5):727-735. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02062

[51] Broms R, Dahlström C, Nistotskaya M. Provider ownership and indicators of service quality: Evidence from Swedish residential care homes. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 2023:muad002.

[52] Bruch J, Zeltzer D, Song Z. Characteristics of private equity–owned hospitals in 2018. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2021;174(2):277-279. doi:10.7326/m20-1361

[53] Bruch JD, Nair-Desai S, Orav EJ, Tsai TC. Private equity acquisitions of ambulatory surgical centers were not associated with quality, cost, or volume changes. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2022;41(9):1291-1298. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01904

[54] Bruch JD, Foot C, Singh Y, Song Z, Polsky D, Zhu JM. Workforce Composition In Private Equity-Acquired Versus Non-Private Equity- Acquired Physician Practices. Health Affairs (Millwood). 42:121-129. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00308

[55] Cerullo M, Yang K, Joynt Maddox KE, McDevitt RC, Roberts JW, Offodile AC 2nd. Association between hospital private equity acquisition and outcomes of acute medical conditions among Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5(4):e229581. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.9581

[56] Cerullo M, Lin YL, Rauh-Hain JA, Ho V, Offodile AC 2nd. Financial impacts and operational implications of private equity acquisition of US hospitals: Study examines the impacts and operational implications of private equity acquisitions of US hospitals. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2022;41(4):523-530. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01284

[57] Cerullo M, Yang KK, Roberts J, McDevitt RC, Offodile AC 2nd. Private equity acquisition and responsiveness to service-line profitability at short-term acute care hospitals: Study examines private equity acquisition at short-term acute care hospitals. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2021;40(11):1697-1705. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00541

[58] Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatology. 2021;157(2):181-188. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5173

[59] Gandhi A, Song Y, Upadrashta P. Have private equity owned nursing homes fared worse under COVID-19? SSRN Electronic Journal. Published online 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3682892

[60] Gandhi A, Song Y, Upadrashta P. Private equity, consumers, and competition: Evidence from the nursing home industry. SSRN Electron Journal. Published online 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3626558

[61] Harrington C, Olney B, Carrillo H, Kang T. Nurse staffing and deficiencies in the largest for-profit nursing home chains and chains owned by private equity companies. Health Services Research. 2012;47(1 Pt 1):106-128. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01311.x

[62] Huang SS, Bowblis JR. Private equity ownership and nursing home quality: an instrumental variables approach. International Journal of Health Economics Management. 2019;19(3-4):273-299. doi:10.1007/s10754-018-9254-z

[63] La Forgia A, Bond A, Braun AM. Association of Physician Management Companies and Private Equity Investment With Commercial Health Care Prices Paid to Anesthesia Practitioners. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2022;182:396-404.

[64] LaFrance A, Batt A, Appelbaum R. Hospital Ownership and Financial Stability: A Matched Case Comparison of a Nonprofit Health System and a Private Equity-Owned Health System. Advances in Health Care Management. 2021;20. doi:10.1108/S1474-823120210000020007

[65] Liu T. Bargaining with private equity: implications for hospital prices and patient welfare. SSRN. 38964. doi:10. 202110.2139/ssrn.3896410.

[66] Nie J, Hsiang W, Marks V, et al. Access to urological care for Medicaid-insured patients at urology practices acquired by private equity firms. Urology. 2022;164:112-117. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.01.055Nie J, Hsiang W, Lokeshwar SD, et al. 5

[67] Nie J, Hsiang W, Lokeshwar SD, et al. Association between private equity acquisition of urology practices and physician Medicare payments. Urology. 2022;167:121-127. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.03.045

[68] Offodile AC 2nd, Cerullo M, Bindal M, Rauh-Hain JA, Ho V. Private equity investments in health care: An overview of hospital and health system leveraged buyouts, 2003-17. Health Affairs (Millwood). 2021;40(5):719-726. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01535

[69] Patwardhan S, Sutton M, Morciano M. Effects of chain ownership and private equity financing on quality in the English care home sector: retrospective observational study. Age and Ageing. 2022;51(12). doi:10.1093/ageing/afac222

[70] Pradhan R, Weech-Maldonado R, Harman JS, Laberge A, Hyer K. Private equity ownership and nursing home financial performance. Health Care Management Review. 2013;38(3):224-233. doi:10.1097/HMR.0b013e31825729ab

[71] Pradhan R, Weech-Maldonado R, Harman JS, Hyer K. Private equity ownership of nursing homes: implications for quality. Journal of Health Care Finance. 2014;42.

[72] Singh Y, Song Z, Polsky D, Bruch JD, Zhu JM. Association of private equity acquisition of physician practices with changes in health care spending and utilization. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(9):e222886. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.288

[73] Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC. Private equity investment and nursing home care: is it a big deal? Health Affairs(Millwood) 2008;27:1399-408.doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1399

[74] Winblad U, Blomqvist P, Karlsson A. Do public nursing home care providers deliver higher quality than private providers? Evidence from Sweden. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2403-0

[75] Bloom, N., Sadun, R. and Van Reenen, J., Does management matter in healthcare. 2014. Boston, MA: Center for Economic Performance and Harvard Business School.

[76] Bloom N, Sadun R, Van Reenen J. Do private equity owned firms have better management practices?. American Economic Review. 2015;105(5):442-6.

[77] Keating E, Oliva R, Repenning N, Rockart S, Sterman J. Overcoming the improvement paradox. European Management Journal. 1999;17(2):120-34.

[78] Nembhard IM, Tucker AL. Deliberate learning to improve performance in dynamic service settings: Evidence from hospital intensive care units. Organization Science. 2011;22(4):907-22.

Notes

[a] As this work builds on Borsa et al.,[1] that work is mentioned often. To reduce citation fatigue due to repetition, we do not provide the citation for Borsa et al. at each mention after this one. All instances of Borsa et al., refer to Borsa A, Bejarano G, Ellen M, Bruch J D. Evaluating trends in private equity ownership and impacts on health outcomes, costs, and quality: systematic review BMJ 2023; 382:e075244 doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-075244