George Stalk, Jr., Senior Advisor and Fellow, The Boston Consulting Group; Joe Manget, Chair and CEO, Edgewood Health Network, Canada

Contact: George Stalk, Jr. stalk.george@advisor.bcg.com

Abstract

What is the message?

There is much talk these days about disruption and disruptors. However, almost nothing is offered to executives on how to respond to a disruptor or even how to be a disruptor. In this article, the authors explain the science and methods of disruptors and, through a case study, EHN Canada, provide an example of a disruptor in action.

What is the evidence?

The observations and conclusions are based on the strategy consulting experiences of George Stalk and Joe Manget at The Boston Consulting Group and the military theories of Col. John Boyd of the USAF and Gen. Heinz Guderian of the German High Command in WW II. Manget is the CEO of EHN Canada that is disrupting its corner of the healthcare industry.

Submitted: May 27, 2019; accepted after review: July 8, 2019.

Cite as: George Stalk, Joe Manget. 2019. The Anatomy of a Disruptor. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 4, Issue 2.

Disruption: Getting from talk to action

When it comes to the risk of disruption, there is more talk than action in the corporate C-suite. Unfortunately, when legacy companies do not take action, disruption becomes a threat rather than an opportunity.

To thwart possible disruption, pundits give legacy companies such advice as “disrupt yourself before you get disrupted” or “put frontline employees in charge of strategy and execution.” This counsel is of little help.

In this case study, Canadian company, Edgewood Health Network (EHN Canada) is an example of a disruptor in action.

Case Study: Edgewood Health Network (EHN)

We are in a healthcare crisis, and “more of the same” will not work. For the first time in recent history, life expectancy in several western countries has flattened or even started to decline. As a society, we have made huge strides in dealing with infectious diseases and, more recently, with chronic diseases, and our average life expectancy has increased each year. However, that progress has stopped, primarily because of an increase in mental health issues leading to suicide, overdose, and other addiction-related issues. Most western countries are now seeing a measurable decrease in life expectancy.

In addition, we have an aging population that is notably less healthy than previous generations, with the incidences of diabetes, Alzheimer’s, obesity, and dementia steadily increasing.

Our healthcare systems are failing to keep up with these increases in demand. Our governments simply to not have enough resources to continue spending the way they have spent on healthcare. Despite all of the hype about digital healthcare and value-based healthcare, healthcare costs per capita are not declining. “More of the same” clearly is not working.

A disruptive model: Applying operations principles to improve cost, quality and time in healthcare

Imagine if in any industry a provider came up with a customer solution that was one-third the cost, with three times better quality, and only took one-sixth the time of the “status quo” competitive offering. If this could be scaled, it could completely disrupt the industry.

Well, this potential to disrupt today’s healthcare system is real. A Canadian company, Edgewood Health Network (EHN Canada), has incorporated leading-edge business and operations practices that dramatically reduce cost, increase positive patient outcomes, and deliver a better patient experience in far less time than the status quo, which in Canada is the public system.

In a previous life, the current CEO of EHN Canada ran the global Operations Practice at The Boston Consulting Group. He has seen business model innovation cross the boundaries of many industries, and was excited to be able to apply these principles to healthcare. EHN Canada operates inpatient, outpatient, and digital mental health and addiction services across the country, but with a next-generation business model. This new model starts with a singular focus on patient outcomes. Any part of the business that does not impact patient outcomes is minimized or eliminated. All resources are directed towards front-line staff and clinical programming. As a result, EHN Canada operates with 95% fewer administrative resources than its public “competitors”, or about one third the operating cost per bed per day. It does this while providing an average of seven hours per day of patient programs, whereas the public system typically provides only one or two hours. The result is that patient outcomes are significantly better than in the public system, and patient satisfaction is close to 100 percent.

EHN Canada also did extensive research into post-treatment outcomes and saw to key drivers of superior outcomes: attending some sort of aftercare for at least one year, and a family/home situation that is supportive of the individual’s recovery. Given the importance of these two factors, EHN Canada decided to bundle them into patient care – one full year of aftercare, in-person or digital, plus a several-day family program where family members come into the facilities to learn more about treatment and recovery and how they can help that process. EHN Canada’s costs are still one third the cost of the public system, which does neither of these.

The other major difference between the new model and the status quo is time. A patient going through the public system for mental health and addiction typically has to wait up to a year for treatment that is higher cost with lower quality outcomes. EHN Canada can treat the same patient in one-sixth of the time of its legacy competitors and gets them back to a productive life faster. Increasingly, some employers are seeing the value of getting an employee suffering from mental health and addiction back to work faster, and are bypassing the public system and seeing real improvements in cost, quality, and timeliness of treatment.

EHN disruption business model: Four key levers

Patient outcomes: The first is the singular focus on patient outcomes. That drives results and gives the company a clear purpose. It also simplifies decision-making and focuses all resources on patient care.

Operational efficiency: The second is a relentless focus on operational efficiency, which requires real-time data and analytics on how each part of the business is operating, whether measuring web traffic or employee morale. Decisions are made quickly based on real-time data, as patient outcomes are improved and non-essential tasks are automated and/or eliminated.

Rapid innovation: The third is rapid innovation. EHN Canada is able to bring new programs and services to market in weeks and months versus years for the public system. For example, a new program to help mothers with children who may not go to addiction treatment because of childcare issues, is being launched this fall. It was a six-month process (it could have been done in three months, but government-issued building permits slowed things down) and will commence operating in January of 2020. This is well within one planning cycle of a typical public healthcare competitor in Ontario, who would very likely take several years, if ever, to bring a new service like this to market.

People: The fourth and by far the most important lever is people. Attracting and retaining talent that is motivated and passionate about positive patient outcomes is critical to EHN Canada. EHN Canada invests heavily in continuous training on the latest clinical techniques to ensure that staff is delivering the highest possible level of care to patients.

This is a bold, new model for healthcare that works. EHN Canada’s longer-term goal is to “bend the cost curve” in healthcare across the country as more “payers” demand improvements and accountability from their “providers” in cost, quality, and timeliness of services. Increasingly, many employers are seeing the value of getting an employee suffering from mental health and addiction back to work faster, and are bypassing the public system and seeing real improvements in cost, quality, and timeliness of treatment.

Adding to the competitive advantage of EHN’s business model are the inabilities of the current public healthcare providers in Ontario from responding due to:

- Lack of awareness from being too inwardly focused

- “Silo-ed” unit management

- The veto power of entrenched bureaucracies

- Denial by top management

- Lack of courage at the top

But even the disruptor can get disrupted

EHN Canada cannot stand still. Many new types of competitors (such as 100 percent digital solutions or extremely low- cost/ very limited service providers) intend to disrupt the market. EHN Canada is constantly looking at these potential disruptors and finding ways to accelerate its own innovation process to develop even better solutions. For example, EHN Canada developed their own digital platform to complement in-person care that dramatically lowers the cost of services while maintaining or improving patient outcomes.

This alone will not be enough. EHN Canada needs to continue to innovate as the next new disruption is around the corner.

Learning to Be a Disruptor: Lessons From Military History

Disruptors like EHN have a pattern to their behavior:

- They do strategy fast

- They make decisions fast

- They execute their decisions quickly, and

- They repeat this cycle again and again at a fast tempo

We believe there is a better way to respond to disruptors than that offered by the pundits. Military history provides needed insight. In 1976, Col. John Boyd (USAF retired, now deceased) explained why U.S. fighter pilots had a far higher “kill ratio” (10:1) than Communist pilots in the Korean War. At the time, the commonly offered explanation was that U.S. pilots were much better trained. If this was true, then dogfight victories should have been evenly distributed among all U.S. pilots. They were not. A few pilots achieved most of the kills and the others very few or none.

Pilot training and the innate ability of each pilot were key factors, but so were the jets themselves. The F-86 that the U.S. pilots flew had vastly superior visibility from the cockpit than the enemy’s MIG 15—and was easier to maneuver at higher speeds. Because of these factors, Boyd postulated that U.S. pilots operated at a much faster tempo than their opponents did:

“…the ability to transition quickly from one maneuver to another was a crucial factor in the victory. Thinking about operating at a quicker tempo – not just moving faster – than the adversary was a new concept in waging war.

“Generating a rapidly changing environment – that is engaging in activity that is so quick it is disorienting and appears uncertain or ambiguous to the enemy – inhibits the adversary’s ability to adapt and causes confusion and disorder that, in turn, causes an adversary to overreact or underreact [Authors’ note: Read “Disruption”.]”(1)

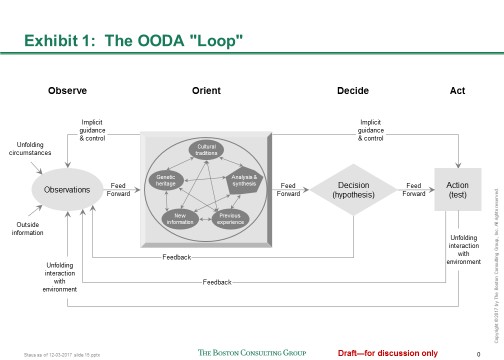

Observe-Orient-Decide-Act: The OODA Loop

Boyd pronounced, “He who can handle the quickest rate of change is the one who survives.”(2) Only a small number of all the U.S. pilots had the ability to drive the tempo of combat until the enemy failed and the U.S. pilot was victorious. This ability was what differentiated the performance of the high scorers from the rest. Boyd labeled this the Observe-Orient-Decide-Act loop, or the OODA loop, shown below:

He later revised the loop to show how to set the tempo of competition:

When explaining the second generation OODA loop Boyd emphasized:

“Note how orientation shapes observation, shapes decision, shapes action, and in turn is shaped by the feedback and other phenomena coming into our sensing or observing window.

“Also note how the entire ‘loop’ (not just Orientation) is an ongoing many-sided implicit cross referencing process of projection, empathy, correlation, and rejection.” (3)

In other words, an aggressor whose OODA loop has a faster tempo than his competitor can get “inside” his competitor’s OODA loop. By the time the competitor reacts, it is too late: the aggressor may be executing his 2nd or 3rd OODA loop while the competitor is still reacting to the 1st loop. The competitor becomes confused, under- or over-reacts, and eventually loses the ability to command and control his situation. In short, the competitor is disrupted!

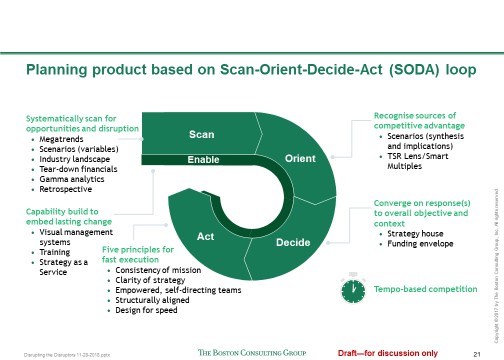

Adapting the OODA Loop for Uncertain Healthcare Environments: Scan, Orient, Decide, and Act (SODA)

Disruptors—the most agile, responsive, and aggressive companies—put the squeeze on competitors with a similar, dynamic loop. However, since the reaction time of a solo pilot is unique to the circumstances and is far faster than that of an organization, we have adjusted the loop to better reflect that reality of business. Our business version has four repeating aspects: Scan, Orient, Decide, and Act (SODA). Disruptors continually scan the landscape, orient themselves to new circumstances, decide how to respond, and act quickly. Then they regroup and repeat the process. With experience and expertise, their SODA loop tightens and tempo accelerates.

Extract from EHN Canada Case Study: The SODA loop in practice

Imagine if in any industry a provider came up with a customer solution that was one-third the cost, with three times better quality, and only took one-sixth the time of the “status quo” competitive offering. If this could be scaled it could completely disrupt the industry.

As a result, EHN Canada operates with 95 percent fewer administrative resources than its public “competitors”, or about one-third the operating cost per bed per day.

EHN Canada can treat the same patient in one-sixth of the time of its legacy competitors and get them back to a productive life faster.

EHN Canada is able to bring new programs and services to market in weeks and months, versus years for the public system.

A tempo advantage relative to the competition is the best long-term insurance against disruption. In any sector, the company that is able to sustain the fastest cycle-time wins. We call this rapid, continuous cycle tempo-based competition.

Disaggregating the SODA loop

To illustrate how the SODA loop works, let’s look at each aspect more closely:

Scan. Since competitors, technologies, and markets can change quickly, companies must systematically scan the horizon both for new opportunities and potential disruptions. Look for trend lines, new customer behaviors, anomalies, unexpected competitors, and changing demand patterns. China’s Alibaba, the massive online marketplace, continually scans its customers’ behaviors by capturing and analyzing more than a petabyte of customer data every day. The insights drive a powerful innovation engine that delivers a continuous stream of new products and platforms. Similarly, Amazon looks for retail categories that are ripe for disruption. It brings these underperforming categories online, cuts costs, makes them more efficient, and improves service. Look for “tipping points” that signify that a new trend or technology is gaining traction. For instance, the explosion in global demand for robotics was preceded by new price, performance, and adoption thresholds of component technologies that signified a tipping point was near. By continuously scanning the landscape, companies maintain an external focus—and avoid becoming complacent or surprised.

Orient. After identifying potential sources of opportunity or disruption, companies must assess where they have gained—or lost—a competitive advantage, and adjust their strategy accordingly. Doing this well requires a diverse leadership team that can analyze different scenarios, discuss and realistically evaluate the choices available, and look beyond the obvious. Depending on the circumstances, options may include the need for a new product to be developed and tested, an offensive move to counter a perceived threat on the horizon, a new set of skills or capabilities, or an acquisition to quickly enter a promising new market. Evaluating the available options and how they affect the current strategy requires time, discipline and a common understanding of the situation throughout the leadership structure. This is a continuous process – it is “always on”.

Decide. Winning over the long term—and avoiding disruption—requires clarity on the key factors that determine competitive advantage. A powerful (and continuous) exercise is for the executive team to identify a short list of critical questions about the business, the answers to which shape the company’s strategy. Potential questions include: Who are our target customers—and how are their needs changing? Will other customer segments become more attractive over time? If so, what would we need to do to win them profitably? Do we have the talent and capabilities we need? Where are we most vulnerable and why? The process of answering these questions typically yields clear strategic decisions and priorities.

Act. Maintaining a rapid tempo requires the fast execution of strategy. Here, larger companies are often at a disadvantage relative to smaller, more nimble ones. To overcome this drawback, the leadership team must distill and clearly articulate the company’s strategic intent and context in the simplest language possible, so that people at all levels of the organization are aligned and can make better decisions more quickly. For instance, Zappos has one overriding mission: to make its customers happy. The company’s service reps know they can do whatever it takes to meet that goal—without having to get approval from their superiors. So they’ll refund defective products and replace them for free, send flowers to a customer’s sick mother, and spend as many hours on the phone as necessary to resolve a problem. To ensure alignment and fast action, individual and team missions must be explicitly linked to the company’s overall mission and strategy. Any incongruities among goals, resources, and constraints must be identified and flushed out early, so that time and effort are not wasted.

A hallmark of tempo-based competition based on the SODA loop is the ability to move more and more quickly through the four steps of the SODA loop as learning and experience accrue. In a larger sense, the SODA loop is a description of scaled learning on a company-wide level.

Challenges to Getting it Right

Simplicity and clarity are not easy to get right. Dr. Gary Klein, an expert on decision making, determined that only 40% of US Marines understood their leaders’ intent—even though the Marines are noted for fast execution.

A particularly well-done piece describing the static aspect of the above is, “Can You Say What Your Strategy Is?” by David J. Collis and Michael G. Rukstad (HBR April 2008)

Market leaders stay ahead—and keep the competition guessing—by changing and improving key aspects of their value proposition and operating model on an ongoing basis. Ralph Hamers, the CEO of ING, put it this way: “Don’t wait for new players or incumbents to compete with you, disrupt you, or disrupt your model. You take the lead. If you feel there’s an opportunity to disrupt and change your business model, do so. It’s very hard to make this decision as a manager or a leader because, basically, you’re cannibalizing your own business.”(4) Quicken is a perfect example of this aggressive strategy in action. Once a traditional mortgage provider, the company shifted to an online focus in the late 1990s. With its online arm, Rocket Mortgage, Quicken Loans makes the mortgage process easy for the average consumer to understand. Today, Quicken Loans is the largest home lender in the U.S.

Taking Advantage of the Opportunity for Tempo-Based Competition

Extract from the EHN Canada Case Study

In the EHN Canada case study above, we noted that EHN gains competitive advantages because current public healthcare providers in Ontario are inwardly focused, operate in silos, face vetoes from entrenched bureaucracies, encounter denial by top management, and often do not have sufficient courage at the top. As a result, faced with these limits in the public sector, some employers are seeing the value of getting an employee suffering from mental health and addiction back to work faster, and are bypassing the public system and seeing real improvements in cost, quality, and timeliness of treatment.

The legacy public health care system of Ontario has much to learn from EHN Canada, a healthcare disruptor. As with most disruptive new models, initially only a few customers switch from the legacy supplier to the disruptor. When the disruptor’s share of what had been the business of the legacy supplier reaches 5-10 percent the disruptor usually cannot be stopped. When the disruptor’s share reaches 15 percent or more the disruptor starts to drive the market.

In the EHN Canada example, many of the most attractive customers – those companies who need their employees with problems to quickly and successfully overcome them and are willing to pay – are now core customers of EHN, arguably leaving less attractive, higher cost to serve patients to the public health care system. But EHN works with several governments across the country to also take these complex patients (such as those suffering from OCD or severe trauma) and has successfully applied its operating model to these patient groups and with outstanding results. The public healthcare system cannot continue to do “more of the same” and must continue to partner with companies such as EHN Canada to be able to provide affordable, high quality healthcare.

*****

We know of no companies whose executives say they are satisfied with the speed and effectiveness of their corporate decision-making and execution processes. They are right to be concerned, because a whole generation of new competitors is arising across almost all sectors of business for whom rapid decision-making and execution is second nature.

Most companies spend far too much time on things that slow people down, use up resources, and add little value. Tempo-based competitors like Quicken, Alibaba, Amazon, and Zappos understand that the best way to avoid disruption is to keep an unwavering focus on the factors that confer a competitive advantage—and to never stand still. If you are standing still, you are a target.

Quotes and references

(1) Reference: Coran, R (15 April 2004) Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of war. Back Bay Books, Reprint edition, ISBN-13: 978-0316796880, Page 328

(2) Boyd, J. R. (1976) New Conception for Air-to-Air Combat (Boyd’s 1976 “Fast Transients” briefing), Page 24

(3) Reference: Coran, R (15 April 2004) Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of war. Back Bay Books, Reprint edition, ISBN-13: 978-0316796880, Page 344

(4) Reference: Hamers, Ralph – On Disrupting the Banking Industry. A Conversation with the CEO of ING (20 September 2016), Boston Consulting Group, No page # as is a web article https://www.bcg.com/en-ca/publications/2016/financial-institutions-people-organization-ralph-hamers-disrupting-banking-industry.aspx