Gregory P. Shea, Ph.D., M.Sc., Jeffrey P. Kaplan, PhD, and Stephen K. Klasko, MD, MBA

Contact: Gregory P. Shea, sheag@wharton.upenn.edu

Abstract

What is the message?

This article outlines a comprehensive approach to designing and evaluating leadership development programs for physicians and non-physicians in Academic Health Centers, including a description of the program design, approaches to assess the program impact, and the results of a combined evaluation of the program’s impact over three years.

What is the evidence?

T1 and T2 administration of the ESCI (Emotional Social Competence Index) 360 instrument and questions on a confidential, end of program evaluation completed separately by the program participants and by their respective sponsors (generally their supervisors) concerning various aspects of the program including its overall value, as well as confidential surveys concerning value of stretch assignments, and the evaluation of individual program sessions.

Submitted: May 18, 2018; accepted after review: July 20, 2018

Cite as: Gregory P. Shea, Jeffrey P. Kaplan, Stephen K. Klasko. 2018. Developing Leadership in Physicians and Non-Physicians. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 3, Issue 2.

Leadership Development in Academic Health Centers

Calls for leadership development in medicine such as those made by Lerman and Jameson (2018) occur within the context of many Academic Health Centers that have or have had such programs.[1] Lucas, et. al., (2018) reported on the prevalence of leadership development programs (LDPs) in Academic Health Centers, with 93 of 94 survey respondents indicating that their institutions provided some type of leadership training and 61 indicating the existence of a formal internal program. In the authors’ opinion, the prevalence of such training and programming did not, however, match rigor in the evaluation of such efforts: “…programs should incorporate more rigorous evaluation beyond satisfaction surveys and strive to find meaningful outcome measures…” [2] (p. 8)

Healthcare providers, educators, and researchers face a turbulent and uncertain environment. Market consolidation of both insurers and providers contribute at least as much to the mix in Philadelphia as elsewhere. Jefferson Health, of course, exists in that environment and has pursued large-scale change both internally (e.g., leveraging technology to better deliver care and education) and externally (e.g., expanding dramatically in size and reach through mergers). Hence, the leadership challenges have centered on developing a new Jefferson, redesigned in its clinical and its business processes and far greater in its size and reach. The Jefferson Leadership Academy was designed to develop enhanced leadership capacity in general and in particular, leadership of change among those in significant organizational roles (albeit not senior leaders) and likely to occupy more significant roles in the future. Findings indicate an impactful program, thereby suggesting a program design for use by others seeking to develop physician and non-physician leadership in academic health systems and in a way that positively impacts the organization.

Program Design

Just over 30 participants began 10 months of classroom work each year, over half of them physicians. Selection began three months earlier and included participants being sponsored (usually by supervisors), completing a several page application, and senior level review. Pre-class work involved a four-way meeting (participant, sponsor, and two program leads—one internal to Jefferson and one external) to reinforce expectations about the course and its demands, as well as to review developmental objectives and possible stretch assignments. Classroom work entailed a full day (at least 8-5) each month. Topics included finance, change leadership, teaming, negotiation, emotional intelligence, diversity and inclusion, marketing, and creativity. Faculty included Jefferson personnel and numerous nationally recognized topic experts. Participation, application sessions, and role play characterized significant portions of classroom work. Session design included special attention to continually ‘shuffling the deck’ in order to maximize networking among program participants. A presentation to and discussion with sponsor and senior management concluded the course. The CEO provided regular and public support of the program (e.g., conducted a session opening the program, attending the program conclusion, and providing funding).

Stretch assignments comprised the second leg of the program and overlapped with the program but did not necessarily begin or end with the classroom portion of the program. Stretch assignments were to include – and, generally, did include – ‘real work’, i.e., work that needed doing, work that mattered to both the participant and to his or her sponsor, and that required the participant to labor outside of his or her normal set of duties and involve others in doing so. Restated, assignments that a participant might do on his or her own or that might only necessitate involvement by current colleagues or staff, would not meet criteria for a good stretch assignment.

Thirdly, and importantly, each participant received two one hour executive coaching sessions each month with a veteran external coach over the final six months of the program. The coaching process included two three-way meetings of sponsor, participant, and coach, initially to set up the coaching process and objectives, and again at the end of the six months to close down the process and to identify next steps. Each participant worked with his or her coach to create a leadership development plan which identified competencies, behavioral objectives, action plans, and metrics. The same executive coaches served as coaches throughout the three years of the program. Inputs to the coaching process included the the Emotional and Social Competence Index, or ESCI, Hogan profile, stretch assignments, participant developmental agenda, and daily work challenges.

Finally, regular ‘crosstalk’ occurred by design among the program staff designing and delivering each of the three aspects of the program. This crosstalk occurred during design, delivery, and debriefing of the program to maximize program integration and focus.

The program design changed minimally over the three years measured.

Measuring Program Effectiveness

Measures of participant leadership skill development were T1 and T2 administration of the ESCI 360 instrument and questions on a confidential, end-of-program evaluation completed separately by the program participant and by their respective sponsors (generally their supervisors). Questions on an end-of-program evaluation completed separately by the program participant and by their respective sponsors (nearly always their supervisors) concerned various aspects of the program including its overall value. Other confidential questioning concerned the value of stretch assignments and the evaluation of individual program sessions. Further measure of program value came from an unanticipated measure.[3]

The Emotional and Social Competence Index, or ESCI, is a 360 degree feedback instrument. It was administered early in the program (in months 2-3) and then again 12 months later, i.e., approximately six months after the program concluded. The initial administration corresponds with the advent of six months of bi-weekly executive coaching, and the second administration provides a way of maintaining participant and sponsor developmental focus. In other words, about one year separated T1 and T2, a gap corresponding to the generally accepted minimum amount of time necessary for behavioral changes to occur and to be noted by others.

The ESCI is a multi-rater coaching and development instrument based on emotional intelligence (EI) research. It is designed to facilitate how people understand how others see them, both strengths and weaknesses, within the domain of EI. Twelve scales comprise the ECSI: achievement orientation, adaptability, coach and mentor, emotional self-awareness, emotional self-control, empathy, influence, inspirational leadership, organizational awareness, positive outlook, and teamwork. Korn Ferry owns and distributes the ESCI.

Raw descriptive statistics provide were collected on all measures. 53 of 95 participants or 56% were physicians.

Outcomes

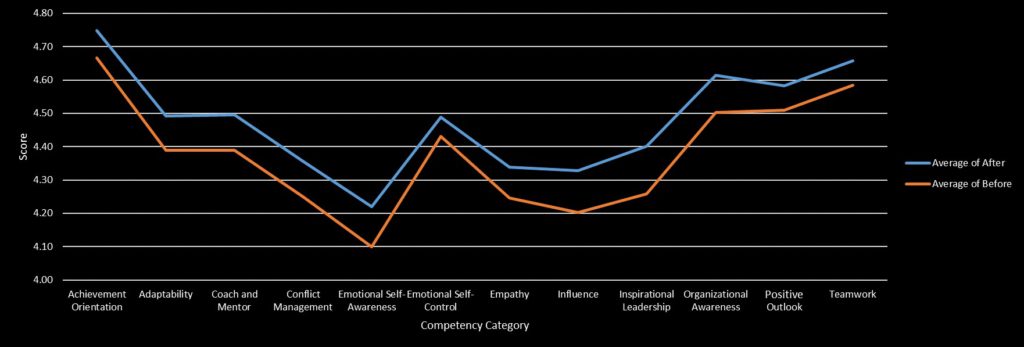

The distribution of T1 and T2 differences in ESCI data met the requirement for paired t-testing, namely it approximated a normal distribution across all categories and all raters. The data for all three cohorts were analyzed to determine statistical significance at the .05 level (using both one and two tailed testing) between T1 and T2 scores, i.e., of the scores at the beginning of the course (i.e., between 2 and 3 months after the beginning of program course work) and the scores approximately 6 months after the end of the course, a calendar time of approximately 12 months. The raw score differences across all years appear graphically in Figure 1 below. Testing for statistical significance by grouping all T1 and T2 scores from all three cohorts combined led to the finding of differences statistically significant at the .05 level for one and for two tailed tests for all 12 competencies. The largest gains were in the areas of (in descending order): Inspirational Leadership, Influence, Emotional Self-Awareness, and three tied (Conflict Management, Coach and Mentor, and Organizational Awareness).

Figure 1: ESCI t1,t2 Average Raw Scores by Competency Averaged Across Cohort

Participants completed a confidential end of program survey. On average, using a seven-point scale, participants, by cohort year, evaluated the overall value of the program for themselves as 6.64, 6.52, and 6.61 and for Jefferson overall as 6.58, 6.65, and 6.65. Sponsors, for their part, when asked if they had seen “visible changes to date in the nature and quality of your sponsored participant’s leadership” responded, by year, on average 6, 5.63, and 5.82 on a scale running from inconsequential (1) to truly noteworthy (7). When asked “would you do it all again?”, sponsors across year responded on average 6.73, 6.5, and 6.6. A sample of stretch assignments appears in Table 1.

| Table 1: Examples of Stretch Assignments |

|

Participants and sponsors offered survey comments in keeping with the above reported numbers. A sample of them appear in Table 2.

| Table 2: Sample Participant and Sponsor Comments about Program Impact |

| Participant: “Leadership Academy [LA]made me a better person, not just a better leader”, “[LA] gave me the awareness of my own leadership abilities, deficiencies, and potential. It taught me the value of finding ways to make others better and trying to build confidence in those around you. It gave me enthusiasm”, “As a physician leader, I never learned the strategies to effect change—I feel better equipped and empowered now”, “[LA] gave me a systematic approach to manage change”, “Rather than a 3-4 year process, the center was open in just over one year”, “[LA] empowered me to effectively communicate and negotiate outside my division and department”, “[LA] provided a tremendous opportunity to network with colleagues from across the enterprise…Also pushed me to be more aggressive and results oriented”, “[LA] has had a powerful impact on me…I recognize myself as a leader here in a way that I never did. I have also built powerful alliances…I am not the same person I was before the program began…”

Sponsor:“[the participant’s] leadership persona has transformed, confidence, analytic approach and team building”, “Participant has shown a major change in focus, particularly his role as team member v. as an individual. Significant ‘Emotional Intelligence’ changes and personality insights”, “…more confident in her leadership style and in making contributions and sharing thoughts that are futuristic, change oriented, and optimistic,” “Incredible transformation over the year”, “Transformative impact on self-identification as a leader—and both the opportunities and responsibilities that implies…”, “Participant grew greatly during the year and will benefit her in the future”, “My participant is significantly better at modulating her response to situations which cause stress…”, “The program has broadened her scope and vision for sure. |

As for the above noted unanticipated measure, in year 3 and now in year 4, 29 of 64 sponsors or 45% of sponsors were either repeat sponsors, i.e., they had sponsored a participant previously, or were program alumni.

Discussion

The program clearly produced observable changes in participant leadership behavior across the competencies measured. Furthermore, participants and their sponsors evaluated the program as impactful and worthwhile, and the program provided the occasion to support projects befitting the stated program goals of improving organizational functioning amid dramatic growth, especially as experienced by patients. Hence, anyone seeking to achieve similar outcomes should consider carefully the program discussed in this article.

That said, as with any case study, the reader is left with questions of causation. These questions carry particular weight for anyone seeking to design and deliver a similar program with similar effect. For example, which program component had the most significant effect? How much did any aspect (e.g., emphasis on participative pedagogy and networking or explicit, public CEO support) contribute to the overall program impact, either in isolation or in combination? How much did the conscious and ongoing attempt to integrate the aspects of the program matter? Did the extensive sponsor involvement, while another example of best practice, play a noteworthy role in program impact? Would a similar program produce similar impact for a different type of cohort? To what extent did timing in the organization’s life, namely new CEO with a change and growth agenda, affect program impact? What is the program ROI and over what time span?

Jefferson Health

Jefferson Health is the brand for Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals Inc, a regional health system and academic medical center which currently has over 30,000 employees. It has grown rapidly over the life of the program under study, i.e., over the last 3 years. Currently, Jefferson Health includes or is scheduled to include the following facilities in greater Philadelphia: Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Center City, Philadelphia, the Jefferson Hospital for Neuroscience, Methodist Hospital in South Philadelphia, Abington Memorial Hospital in the northern suburb of Abington, hospitals and various clinics of Aria Health in Northeast Philadelphia and Lower Bucks County, Kennedy Health facilities in southern New Jersey, and the Einstein Healthcare Network of the Delaware Valley along with 14 international affiliations. All told, Jefferson clinical personnel handle about 4.3m patient interactions a year.

Thomas Jefferson University’s roots go back to 1825. In July 2017, Thomas Jefferson University and Philadelphia University combined and created the newly named Jefferson University (9 colleges, 4 schools, and 160 undergraduate and graduate degrees). Additionally, Jefferson has over $122m in research funding.

References

- Lerman, C and Jameson, L. “Leadership Development in Medicine”, New England Journal of Medicine, 378;20: 1862-1863.

- Lucas, R, Goldman EF, Scott AR, Dandar V. “Leadership Development Programs at Academic Health Centers: Results of a National Survey”, Academic Medicine 2018; 93: 229-36.

- Boyatizis, RE. “Commentary on Ackley (2016): Updates on the ESCI as the Behavioral Level of Emotional Intelligence”, Consulting Psycology Journal: Practice and Research, 2016; v68, no.4: 287-293.

Amdurer, E Boyatzis, RE Saatcioglu, Smith ML, Taylor SN. “Long Term Impact of Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Intelligence Competencies and GMAT on Career and Life Satisfaction and Career Success”, Frontiers in Psychology, 2014, Dec, v5, article 1447: 1-15.