Rachel A. Hadler, MD1*, Julia F. Lynch, PhD2*, Julia Berenson, MSc3, Lee A. Fleisher, MD1

Contact: Rachel A. Hadler, Rachel.hadler@uphs.upenn.edu

* These authors contributed equally to this work.

Acknowledgements: This project was partially funded by a 2013 Pilot Grant from the Leonard Davis Institute for Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. Findings from this study were previously presented by R. Hadler and J. Berenson at Academy Health in Boston in June, 2016.

Abstract

What is the message?

We evaluated perceptions of the desirability and quality of care provided by nurse practitioners and physicians, as well as the acceptability of different trade-offs allowing direct access to physician providers. Significant segments of the public perceived physician-provided care as preferable to team-based care. Respondents more likely to support ungated access to physicians were nonwhite, experiencing financial hardship, older, and/or identified as Republican. Similar characteristics predicted perceptions that seeing a nurse practitioner resulted in worse care and willingness to pay to guarantee direct access to physicians without seeing an NP first. There was little political consensus on acceptability of specific trade-offs that might facilitate increased physician access.

What is the evidence?

An internet-based survey of 3650 U.S. citizens exposed to sample care scenarios with nurse practitioners or physicians as primary provider across multiple care settings and insurance types and asked to evaluate quality and desirability of care.

Submitted: May 18, 2018; accepted after review: July 20, 2018

Cite as: Rachel A. Hadler, Julia F. Lynch, Julia Berenson, Lee A. Fleisher. 2018. Limited Public Support for Team-Based Care Models: Survey Results. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 3, Issue 2.

Introduction

The past decade has seen significant change in the federal approach to health care delivery in the United States. The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 was hailed by liberals as an important step towards universalizing access to care, but scorned by conservatives as costly and emblematic of government overreach.[1] In spite of ongoing debate and generally negative perceptions in the polls,[2] [3] [4] coverage under the ACA has continued to expand over the seven years since its enactment,[5] generating an increased need for healthcare providers[6]. In early discussions regarding expected workforce shortages, the team-based care model, which involves collaborative delivery of care by physician and non-physician providers such as nurse practitioners (NPs), was hailed as a means of expanding the healthcare workforce[7] [8] and allowing insurance plans to meet requirements for minimum guaranteed benefits while containing costs.[9] [10] [11] [12] [13]

Existing research indicates that patients enjoy similar outcomes whether seen by a nurse practitioner or physician, [14] [15] suggesting that non-physician providers could address the shortage of primary care doctors as long as appropriate systems for escalation were in place. [16] [17] While studies have found that the public is generally enthusiastic about nurse practitioners as primary care and outpatient specialist providers,[18][19] less is known about the public’s understanding or acceptance of team-based care models in non-routine settings, and there is no research on how these attitudes are related to political partisanship, a key predictor of healthcare policy attitudes.

Existing research on consumer attitudes towards tiered access to care based on hospital or provider characteristics suggests that the public is wary but not unequivocally opposed to such a model if it is accompanied by significant gains in quality.[20] [21] Given this context, we chose to examine public attitudes toward the quality and desirability of a team-based care model in which nurse practitioners act as primary providers with physician backup. Our goal in fielding this nationally representative survey was to assess public acceptance of rationed access to physicians by insurance providers across several distinct clinical contexts.

Methods

Study design

We used an experimental design embedded in a survey (Appendix) to estimate the effect on respondents’ support for limiting access to physician providers based on the type of insurance held by a fictitious patient and the setting in which care was sought. This type of experimental design has been used extensively in health policy research to circumvent some of the limitations of traditional cross-sectional surveys and to clarify the relationships identified by classic survey work.[22] [23] [24] Heart disease was selected as a pathology of interest based on existing precedents for advanced practice provider (APP)-driven care in the outpatient environment.[25] [26] [27]

The survey was developed in collaboration with colleagues in healthcare and policy, and was pre-tested for clarity on a convenience sample of respondents using Survey Monkey. It was fielded in August 2014 by YouGov, an Internet-based market research firm that also fields scholarly surveys. Respondents were American citizens over 18 years of age enrolled in YouGov’s opt-in Internet panel.

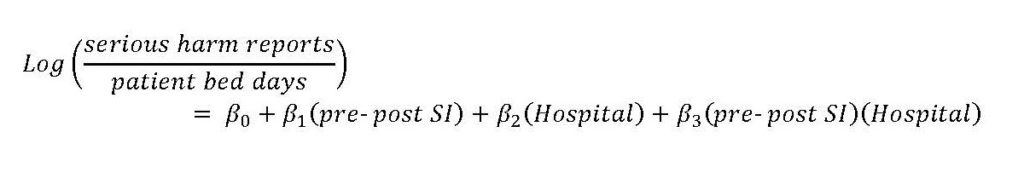

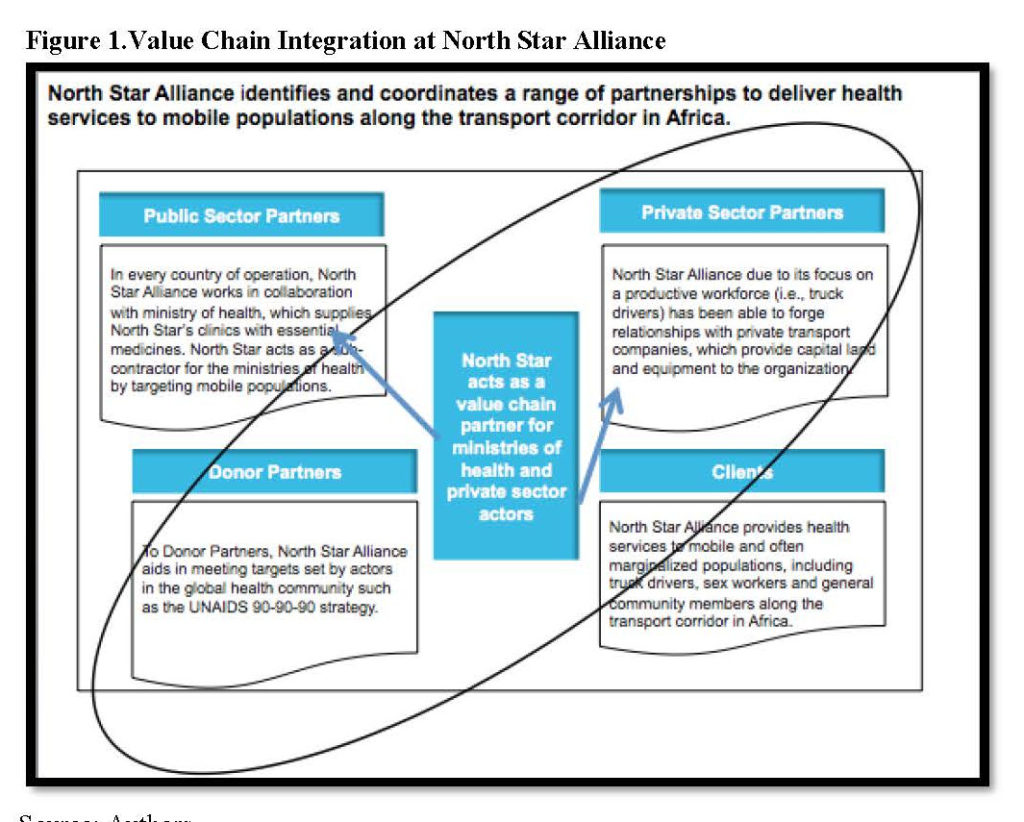

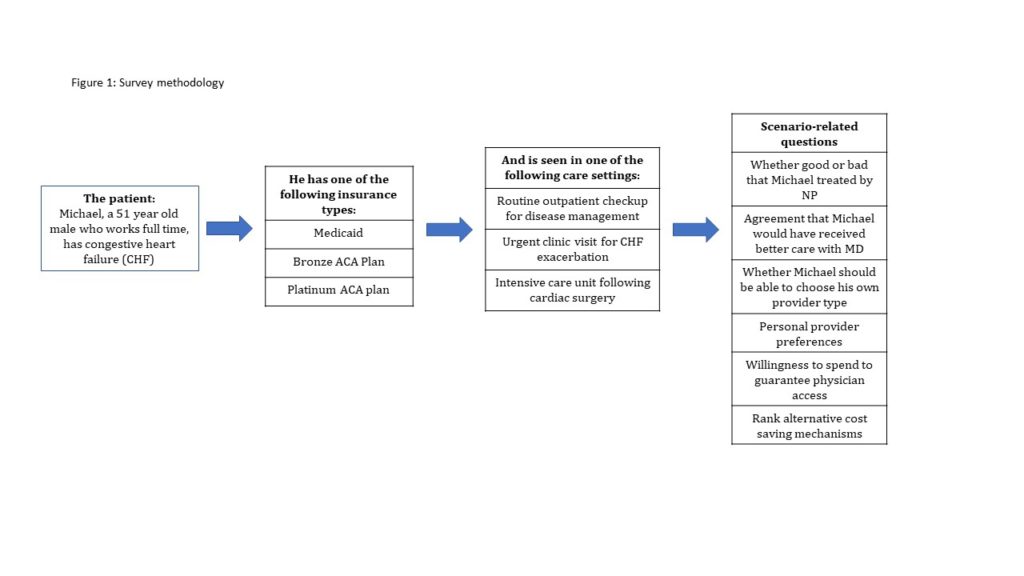

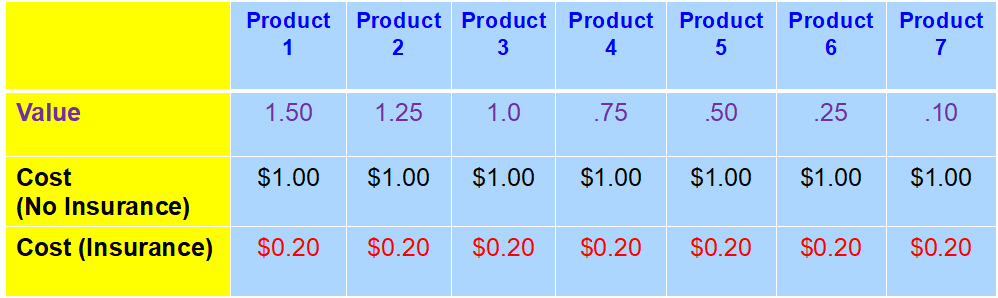

After responding to several questions assessing pre-treatment attitudes towards healthcare and policy, participants were exposed to a brief informational module explaining the degree of federal subsidization for three levels of insurance under the ACA, and tested to ensure that the relevant information was salient. They were then presented with one of nine possible vignettes describing a male patient who has heart failure (HF) and whose insurance “will only cover the costs for him to see a doctor if a nurse practitioner could not provide the same care.” Two aspects of the patient’s care vignette were randomly manipulated for each respondent: (1) health insurance type and (2) care setting. (Figure 1)

Following the vignette, respondents were asked to evaluate the quality and cost of care received from the assigned provider before answering questions about their provider preferences and willingness to pay to guarantee direct access to a physician. Respondents then ranked a variety of alternatives to limiting direct access to physicians as means of reducing/ stabilizing healthcare costs: 1) increased insurance premiums; 2) longer wait times; 3) increased out of pocket costs for medication; 4) increased out of pocket expenses for office visits; 5) reduced subsidies for low income populations; and 6) increased taxes to increase resources for health care. Respondents were also asked to provide demographic data.

Statistical Methods

Sample weights provided by YouGov were used to correct for observable imbalances between responders and nonresponders, and to weight individuals to a nationally representative sample. Initial descriptive analysis involved comparing mean responses for opinion questions across all nine treatment groups. In keeping with conventions in attitudinal research, Likert scales were treated as linear.

Linear regressions were performed to evaluate the mean effect of the care setting and insurance type manipulations among subgroups of survey respondents. Multinomial logit models were used to analyze how cost control options were affected by the insurance and care setting treatments. Ordinal least squares (OLS) models were used to predict the relationship between the insurance treatment conditions and opinions about provider choice, as well as to predict the relationship between treatment conditions and opinions about the desirability of specific policy options which would allow increase physician access. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA (V14, College Station, TX).

Results

Our survey had a within-panel response rate (AAPOR 4) of 55% (of 8255 YouGov panelists invited, 4357 elected to participate). Non-responders were statistically indistinguishable from responders in terms of household income and political party identification, but were more likely than respondents to be male, non-white, and have lower educational attainment. From these respondents, the 3,650 respondents included in the final sample were weighted to a nationally representative sampling frame matched on voter registration status and turnout, interest in politics and party identification, age, gender, race/ethnicity, educational attainment and ideology.

The survey indicated a substantial preference for physicians over non-physicians, with several factors reinforcing the preference. A large majority of respondents (79%) supported insurance companies allowing patients having direct access to physician providers regardless of care setting or insurance type (Table 1). Nonwhite respondents, those experiencing financial hardship, older respondents, and Republicans were more likely to report a personal preference for being seen by a physician provider.

Table 1: Support for ungated access to physician providers by care setting and insurance treatments

| Care Setting Treatment | Insurance Condition Treatment | ||||||

| Total sample (%) | Outpatient

Routine (%) |

Outpatient Acute (%) | Inpatient (%) | Medicaid (%) | Bronze (%) | Platinum (%) | |

| Michael should be able to choose to see a physician | |||||||

| Disagree Strongly | 5.0 | 4.1 | 6.4 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 4.7 | 3.8 |

| Disagree somewhat | 18.0 | 18.4 | 16.9 | 18.8 | 22.2 | 18.1 | 13.8 |

| Agree somewhat | 40.6 | 40.5 | 40.0 | 41.2 | 40.6 | 42.8 | 38.4 |

| Agree Strongly | 36.4 | 36.9 | 36.7 | 35.6 | 30.6 | 34.5 | 44.0 |

Financial hardship, fair or poor self-assessed health status, and older age were predictive of willingness to pay an additional fee for guaranteed access to a physician (nonwhite, uninsured, age and Republican), and of perceiving that a nurse practitioner would provide worse care for the fictitious patient than would a physician. Respondents’ belief that physician care would be preferable in this scenario, their personal preference to be seen by an MD under similar circumstances, and the amount they would be willing to pay to ensure ungated access to a physician were all strong predictors of support for the vignette protagonist having ungated access to physician providers.

Political ideology strongly conditioned the effect of the insurance treatment on opinions regarding the desirability of ungated provider choice (p<0.05; Table 2). Although both liberals and conservatives exposed to the Platinum insurance treatment supported ungated access to physicians, conservatives exposed to the Medicaid insurance treatment were significantly less likely than liberals to agree that patients like the vignette protagonist should have provider choice. Similar patterns emerged across surrogates for political partisanship such as conservatism and low egalitarianism score.

Table 2: OLS regression coefficients (p-values in parenthesis) for models predicting support for ungated access to physician providers

| A | B | C | D | E | |

| Insurance Treatment | |||||

| Platinum | 0.1029 (0.022) | 0.1002 (0.023) | 0.9787 (0.026) | 0.1005 (0.022) | 0.1034 (0.135) |

| Medicaid | -0.1476 (0.002) | -0.1465 (0.001) | -0.1600 (0.000) | -0.1581 (0.000) | -0.2248 (0.001) |

| Demographics | |||||

| Nonwhite | 0.03964 (0.371) | 0.008418 (0.849) | -0.03100 (0.491) | -0.02664 (0.551) | |

| Under 400% poverty | 0.04852 (0.244) | 0.03680 (0.375) | 0.03395 (0.412) | 0.03150 (0.444) | |

| Financial hardship | 0.07762 (0.000) | 0.05651 (0.008) | 0.05819 (0.006) | 0.06374 (0.003) | |

| Some/ 2-year college | -0.04693 (0.305) | -0.03483 (0.444) | -0.03509 (0.441) | -0.03207 (0.475) | |

| 4-year college/ post-graduate work | -0.1667 (0.000) | -0.1327 (0.006) | -0.1368 (0.005) | -0.1386 (0.004) | |

| Fair/ poor health status | -0.02477 (0.624) | -0.03059 (0.540) | -0.03504 (0.479) | -0.04206 (0.386) | |

| Uninsured | -0.01409 (0.816) | 0.05852 (0.325) | 0.05408 (0.365) | 0.04512 (0.446) | |

| Currently insured under Medicaid | 0.08744 (0.185) | 0.09591 (0.147) | 0.08630 (0.193) | 0.07812 (0.229) | |

| Currently insured under Medicare | 0.05527 (0.301) | 0.09761 (0.069) | 0.09203 (0.087) | 0.09029 (0.090) | |

| History of heart attack | 0.006755 (0.873) | 0.1989 (0.630) | 0.02143 (0.603) | 0.02177 (0.594) | |

| Age | 0.01954 (0.002) | 0.01868 (0.002) | 0.01816 (0.003) | 0.01930 (0.001) | |

| Age-squared | 0.0002053 (0.002) | 0.000213 (0.001) | 0.000205 (0.001) | 0.0002161 (0.000) | |

| Personal preferences | |||||

| Personally prefer to see physician | 0.1581 (0.000) | 0.1575 (0.000) | 0.1569 (0.000) | ||

| Amount willing to pay | 0.02660 (0.001) | 0.02745 (0.000) | 0.0273 (0.000) | ||

| Bad for Michael to see NP | 0.06015 (0.006) | 0.06170 (0.005) | 0.05496 (0.011) | ||

| Political party | |||||

| Democrat | 0.04448 (0.311) | 0.02911 (0.695) | |||

| Republican | -0.7792 (0.077) | -0.1631 (0.019) | |||

| Interactions | |||||

| Platinum/ Democrat | -0.1673 (0.107) | ||||

| Platinum/ Republican | -0.16305 (0.019) | ||||

| Medicaid/ Democrat | 0.1948 (0.063) | ||||

| Medicaid/ Republican | 0.01444 (0.889) | ||||

| R-Squared | 0.0146 | 0.0439 | 0.1273 | 0.1298 | 0.1418 |

We found widespread agreement that ungated access to physician providers was desirable. However, few respondents, regardless of political affiliation, expressed willingness to sacrifice other aspects of value in order to finance ungated physician-level care for all patients. Table 3 reports the share of respondents endorsing policy changes such as higher premiums, longer wait times, or reduced subsidies to allow ungated access. Fewer than one in ten respondents definitively endorsed any of the policy solutions, and no more than one in four was willing to voice even qualified acceptance of the options listed.

Table 3: Share of respondents endorsing policy options to free up resources for ungated access to physician providers

| Policy Option | Definitely Good | Possibly Good | Possibly Bad | Definitely Bad |

| Increase insurance premiums for all patients | 5.6 | 18.6 | 33.2 | 42.7 |

| Have all patients wait longer to see a specialist for nonemergent visits | 4.6 | 25.0 | 37.4 | 33.0 |

| Increase copays for medications | 3.2 | 13.7 | 34.9 | 48.2 |

| Increase copays for visits to medical office | 3.2 | 18.2 | 34.9 | 43.6 |

| Cut back subsidies for health insurance for people with low incomes | 8.5 | 22.6 | 29.6 | 39.3 |

| Raise taxes | 6.99 | 23.3 | 25.9 | 43.9 |

When faced with a forced choice, over half of respondents favored either raising taxes or lowering subsidies in order to ensure ungated access to physicians. The choice of these options was highly partisan (Table 4): 46% of liberals and only 8% of conservatives endorsed raising taxes as the most desirable option, whereas 40% of conservatives and only 12.5% of liberals supported reducing insurance subsidies for low-income people.

Table 4: Share of respondents endorsing first and second choice policy options, by political ideology

| Political Ideology | ||||

| Total Sample (%) | Conservative (%) | Moderate (%) | Liberal (%) | |

| First policy choice | ||||

| Reduce subsidies for health insurance for people with low incomes | 25.9 | 39.8 | 23.4 | 12.5 |

| Raise taxes | 25.5 | 8.4 | 26 | 45.6 |

| Second policy choice | ||||

| Reduce subsidies for health insurance for people with low incomes | 8.6 | 9.7 | 8.8 | 7 |

| Raise taxes | 8.5 | 4.6 | 10 | 11.1 |

Discussion

Despite widespread enthusiasm in the health policy community for team-based care models,9 the American public remains skeptical about insurance restrictions that would limit direct access to physicians. The public’s unequivocal endorsement of unfettered provider choice is in line with other studies suggesting that despite incentives encouraging use of low-cost, high-quality providers,[28] [29] uptake has been limited. Factors influencing these consumer choices may include perceptions that lower cost providers provide lower quality care[30] as well as loyalty to specific providers[31][32] and trusted referral sources.21

Our research also reveals a stark political divide in attitudes toward cost savings in healthcare. While liberals and conservatives agree on the undesirability of the gated access to physician-level providers central to team-based care for those with insurance plans with no federal subsidy, they disagree about whether patients with subsidized plans should have unrestricted access to physician care, and about how to pay for this guaranteed access to physicians.

Many policymakers see an important role for team-based care. Team-based care has been associated with reduced readmission rates;30 numerous evaluations of care provided by nurse practitioners in primary care settings have shown higher patient satisfaction rates with similar outcomes and costs in comparison to physicians. [33], [34] A 2001 Institute of Medicine Report called for an enhanced role of team-based care in future healthcare.[35] In spite of this, our findings suggest that many Americans, particularly those most likely to be impacted by such a policy change, continue to perceive physician-driven care as more desirable.

This combination of enthusiasm among policy elites and skepticism among the public is reminiscent of the debates over the introduction of Health Management Organizations (HMO) in the 1980s and 1990s. The poor outcomes of most HMO initiatives should serve as a reminder that unfavorable public opinion can derail even policies that receive widespread political endorsement and public utilization. If team-based care models are to avoid the fate of HMOs, health policy makers must educate the public about their cost effectiveness and quality, and find ways to overcome partisan divides underlying healthcare attitudes.

The nature of our sample imposes some limits on the generalizability of our findings. YouGov’s online panel, from which our sample was drawn, is weighted to match the national population in terms of gender, age, race, education, political party identification, ideology, and interest, voter registration and turnout. Survey weights further correct for any random imbalances with respect to the national population. The uninsured and Medicare recipients are nevertheless somewhat overrepresented in our survey’s weighted sample as compared to the 2014 Current Population Survey (CPS),[36] whereas Medicaid patients are underrepresented. Although our analysis controls for insurance status, this feature of the sample should be taken into account when extrapolating our findings to a national frame.

Although the methodology has been used in other health policy work[23] [24], the central questions in our survey are new and unvalidated. Our survey instrument framed the restrictions on physician access in the context of insurance, rather than as a change induced by incentives in the ACA or at the initiative of medical practice groups. In fact, all of these actors have pushed in the direction of more team-based care. Given the hostility of many Americans to insurance companies, this framing may result in a more negative view among respondents toward the use of NPs as first-line providers. Finally, our survey assesses respondents’ opinions in response to written clinical vignettes, which may not accurately represent their behavior in real-world care-seeking situations.

This study suggests that policy makers interested in reducing health care costs through gated access programs have three choices: (1) to maintain the status quo, whereby access to physician providers is rationed according to ability to pay, a solution that is objectionable to many members of the public; (2) to forge a consensus on policy measures that could be undertaken to finance more widespread access to physicians; or (3) to educate the public about the benefits of team-based care. We believe that some combination of the three is probably an optimal compromise solution, given the wide divergence between political groups on the desirability of other cost-saving measures, differences of opinion about the desirability of tiering access to physicians by insurance, and the current gap between expert and lay beliefs.

Appendix

Tiering-Hadler-Appendix-Survey Instrument

References

- Pew Research Center. More Americans disapprove than approve of health care law. 2016 Apr 27. [cited 2016 Sept 28]. In Pew Research Center: U.S. Politics and Policy [Internet]. Philadelphia (PA): Pew Charitable Trust. Available from: http://www.people-press.org/2016/04/27/more-americans-disapprove-than-approve-of-health-care-law/.

- Blendon RJ and Benson JM. Voters and the Affordable Care Act in the 2014 Election. New England Journal of Medicine 2014;371:1-7.

- Jones, Jeffrey M. Americans’ views of healthcare law improve. 2015 July 10. [Cited 2016 September 28]. In Gallup News: Politics [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Gallup, Inc. Available from: http://www.gallup.com/poll/184079/americans-views-healthcare-law-improve.aspx.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health Tracking Poll: the public’s views on the ACA. 2016 Sept 27. [Cited 2016 Sept 27]. In KFF.org [Internet], Menlo Park (CA): Kaiser Family Foundation. Available from: http://kff.org/interactive/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-the-publics-views-on-the-aca/#?response=Favorable–Unfavorable&aRange=twoYear.

- McMorrow S, Polsky, D. Issue Brief: Insurance coverage and access to care under the Affordable Care Act. 2016 Dec 8. [Cited 2017 Aug 17]. LDI ACA Impact Series [Internet]. Philadelphia (PA), Leonard Davis Institute. Available from: https://ldi.upenn.edu/brief/insurance-coverage-and-access-care-under-affordable-care-act).

- Heisler EJ. Physician supply and the Affordable Care Act. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2013 Jan. Report No. R42029. Available from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0630/1e4333be895712830e9c5f0f1dfd8a8fa2f5.pdf.

- Auerbach DI, Chen PG, Friedberg MW, Reid R, Lau C, Buerhaus PI, Mehrotra A. Nurse-managed health centers and patient-centered medical homes could mitigate expected primary care physician shortage. Health Affairs. 2013;32:1933-1941.

- Green, LV, Savin S, Lu Y. Primary care physician shortages could be eliminated through use of teams, nonphysicians, and electronic communication. Health Affairs. 2013;32:11-19.

- Essential Health Benefits Requirements Act of 2010. Pub. L. 111-148, 124 Stat.782 (Mar 23, 2010).

- Public Health Service Act of 1944, 42 U.S.C. Ch 6(a),§ 300gg (2010).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Insurance Standards Bulletin Series–Extension of Transitional Policy through October 1, 2016. Available from: http://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Regulations- and-Guidance/Downloads/transition-to-compliant-policies-03-06-2015.pdf.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Standards Related to Essential Health Benefits, Actuarial Value, and Accreditation. Federal Register 2013;78:12834-12872.

- Giovannelli J, Lucia KW, and Corlette S. Implementing the Affordable Care Act: Revisiting the ACA’s Essential Health Benefits Requirements. Commonwealth Fund 2014; 1783:1-12.

- Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. British Medical Journal. 2002;324: 819–23.

- Naylor MD and Kurtzman ET. The Role Of Nurse Practitioners In Reinventing Primary Care. Health Affairs. 2010;29:893-899

- Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. Transforming Primary Care: From Past Practice To The Practice Of The Future. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):779-84

- Grumbach K and Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:1246–51.

- Dill MJ, Pankow S, Erikson C, Shipman S. Survey Shows Consumers Open To A Greater Role For Physician Assistants And Nurse Practitioners. Health Affairs. 2013;32:1135-1142.

- Brown DJ. Consumer perspectives on nurse practitioners and independent practice. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2007;19:523-529.

- Harris KM. Can high quality overcome consumer resistance to restricted provider access? Evidence from a health plan choice experiment. Health Services Research. 2002;37:551-71.

- Sinaiko AD. How do quality information and cost affect patient choice of provider in a tiered network setting? Results from a survey. Health Services Research. 2011;46:437-56.

- Gaines BJ and Kuklinski JH. The logic of the survey experiment reexamined. Political Analysis. 2007;15:1-20.

- Gollust SE, Lynch J. Who deserves health care? The effects of causal attributions and group cues on public attitudes about responsibility for health care costs. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 2011;36:1061-1095.

- Tesler M. The spillover of racialization into health care: how President Obama polarized public opinion by racial attitudes and race. American Journal of Political Science 2012;56:690-704.

- David D, Brittling L, Dalton K. Cardiac acute care nurse practitioner and 30-day readmission. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2015;30:248-255.

- Hall MH, Esposito RA, Pekmezaris R, Lesser M, Moravick D, Jahn L, Blenderman R, Akerman M, Nouryan CN, Hartman AR. Cardiac surgery nurse practitioner home visits prevent coronary artery bypass graft readmissions. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2014;97:1488-1493.

- Lowery J, Hopp F, Subramanian U, Wiitala W, Welsh DE, Larkin A, Stemmer K, Vaitkevicius P. Evaluation of a nurse practitioner disease management model for chronic heart failure: a multi-site implementation study. Congestive Heart Failure. 2012;18:64-71.

- Brennan TA, Spettell CM, Fernandes J, Downey RL, Carrara LM. Do managed care plans’ tiered networks lead to inequities in care for minority patients? Health Affairs. 2008;27:1160-116.

- Tackett S, Stelzner C, McGlynn E, Mehrotra A. The impact of health plan physician-tiering on access to care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2011;26:440-445.

- Mehrotra A, Hussey PS, Milstein A, Hibbard JH. Consumers’ and providers’ responses to public cost reports, and how to raise the likelihood of achieving desired results. Health Affairs. 2012;31:843-851.

- Ehman KM, Deyo-Svendsen M, Merten Z, Kramlinger AM, Garrison GM. How preferences for continuity and access differ between multimorbidity and healthy patients in a team care setting. Journal of Primary Care and Community Health. 2017;1-5.

- Sinaiko AD, Rosenthal MB. The impact of tiered physician networks on patient choices. Health Services Research. 2014;49:1348-1363.

- Laurant M, Reeves D, Hermens R, Braspenning J, Grol R, Sibbald B. Substitution of doctors by nurses in primary care. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005:CD001271.

- Liu H, Robbins M, Mehrotra A, Auerbach D, Robinson BE, Cromwell LF, Roblin DW. The impact of using mid-level providers in face-to-face primary care on health care utilization. Medical Care. 2017;55:12-18.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 2001.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey, 2014 Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/techdocs/cpsmar14R.pdf.

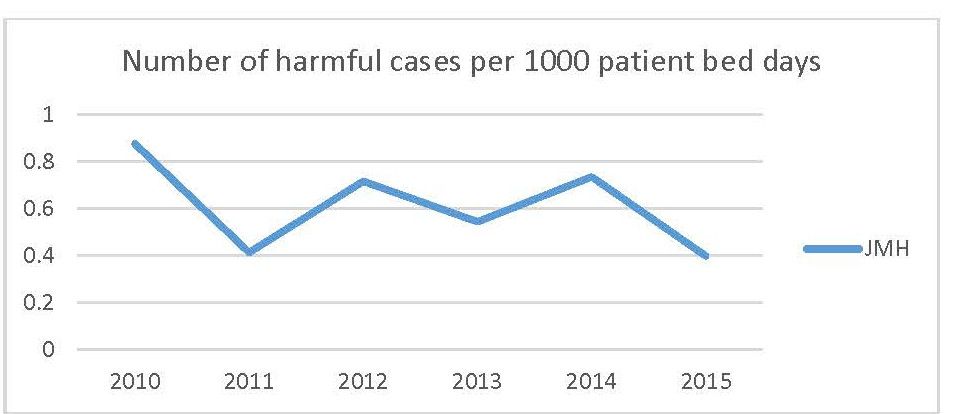

Legend: Rate per 1000 patient bed days of Quantros G, H, and I reports per 1000 patient bed days by year.

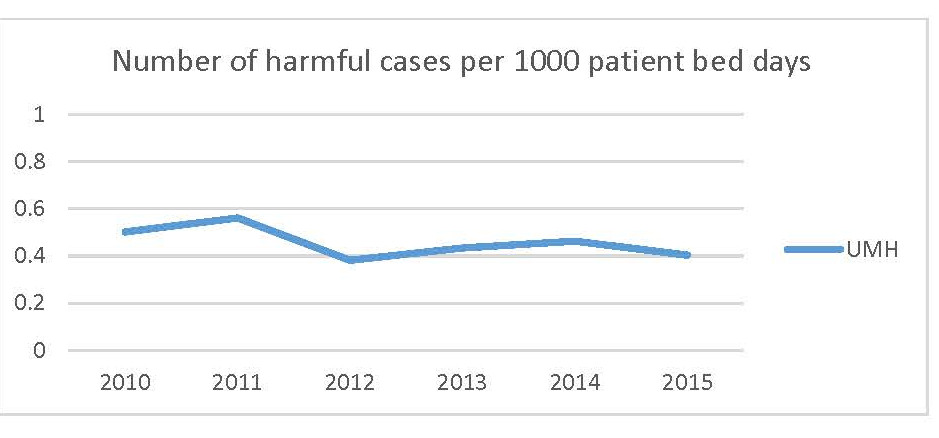

Legend: Rate per 1000 patient bed days of Quantros G, H, and I reports per 1000 patient bed days by year.