Regina E. Herzlinger, Harvard Business School, and Kevin A. Schulman, MD, Duke University School of Medicine

Contact: Regina E. Herzlinger, rherzlinger@hbs.edu

Regina E. Herzlinger is the Nancy R. McPherson Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School. She was the first woman to be tenured and chaired at Harvard Business School and the first to serve on many established and start up corporate health care /medical technology boards.

Kevin A. Schulman, MD, MBA is a professor of medicine at Duke University. He is an associate director of the Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI), the world’s largest academic clinical research organization. He is also the founding president of the Business School Alliance for Health Management (BAHM).

Abstract

What is the message?

Business model innovations that successfully meet health care challenges commonly have two features:

• Successful innovations focus on only one of three opportunities: Consumer-facing activity; system integration; or technical advance.

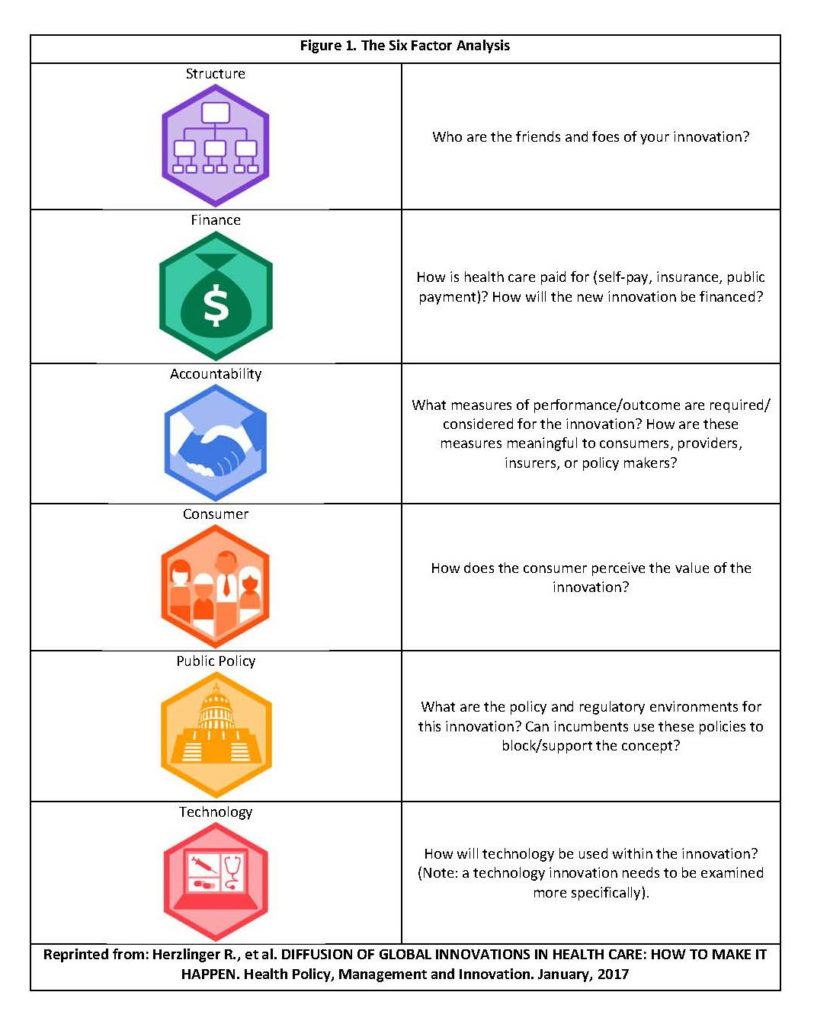

• Successful innovations align well with six factors in their political and economic environments: Market structure; financing; consumers; public policy; accountability; and technology.

What is the evidence?

These recommendations draw from multiple case studies of organizations operating in emerging markets with innovations that have implications for “reverse innovation” to traditional developed markets.

Links: Slide

Submitted: August 21, 2016; Accepted after review: October 30, 2016

Cite as: Regina E. Herzlinger and Kevin A. Schulman. 2017. Diffusion of Global Innovations In Health Care: How To Make It Happen. Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 2, Issue 1.

Introduction

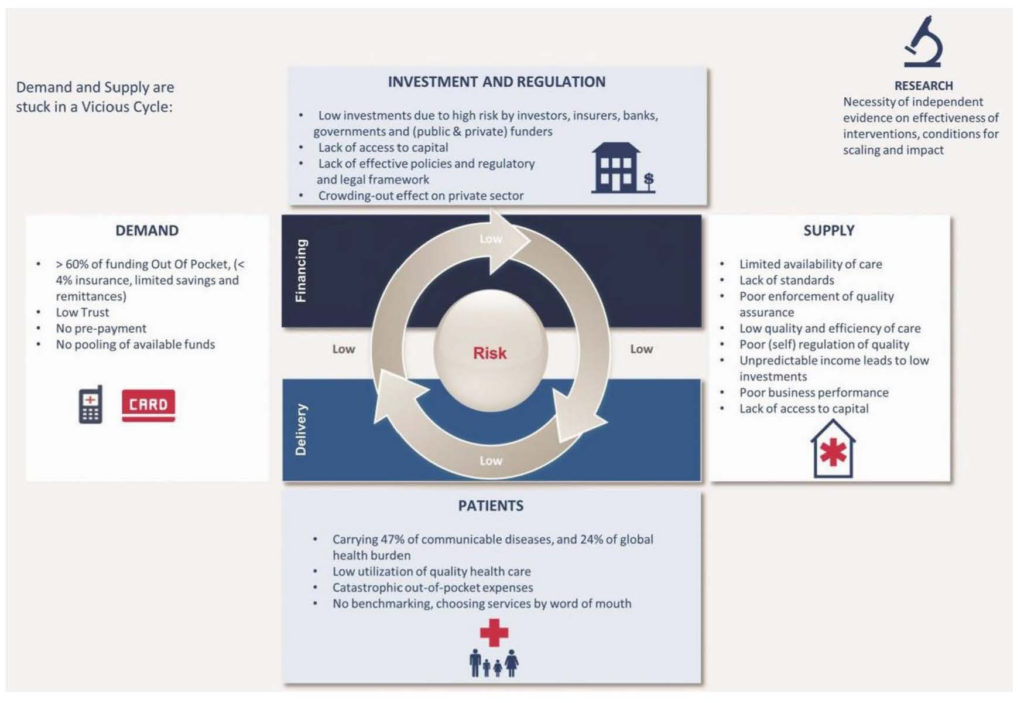

Health care faces daunting challenges globally. The supply of health care services is constrained by the inefficiency of service models, limits in workforce capacity, and the need for capital investments in critical infrastructure. Simultaneously, demand is growing through the transition from communicable to non-communicable diseases and population aging.

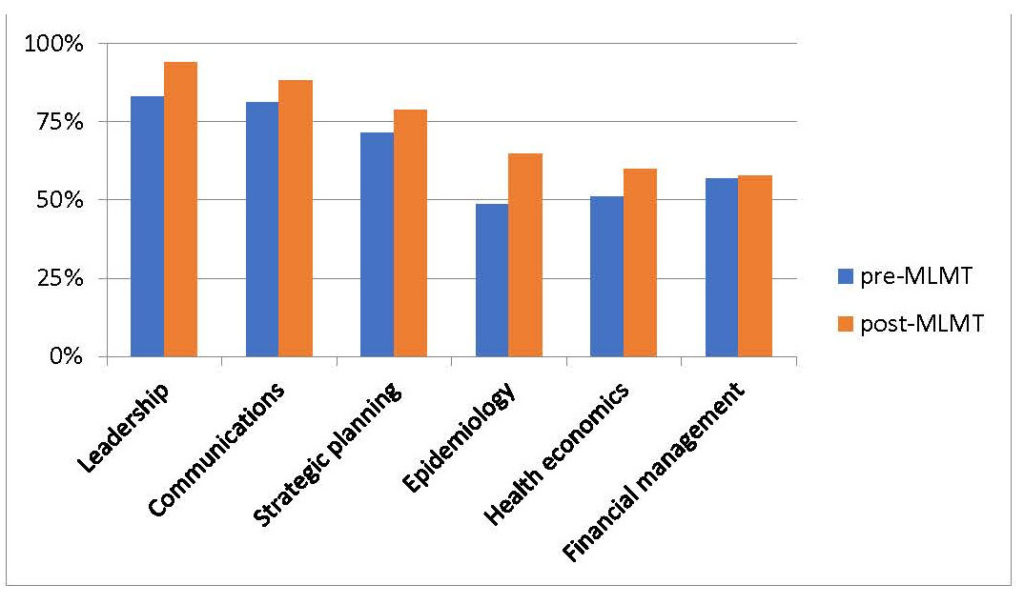

This article highlights examples of successful reverse innovations. We clarify the basis of their success by placing the cases within a health care framework that identifies the core purpose of the innovations and their alignment with six key environmental factors (see Figure 1): Market structure, financing, consumers, policy, accountability metrics, and technology (2).

Examples of Successful Health Care Reverse Innovations

The cases below describe how these “do good and do well” innovations expanded globally, benefiting from choices of operating focus and alignment with the six environmental factors.

1. Longer Term Bundles for Chronic Diseases: Health Care Global (India)

Dr. B.S. Ajaikumar, CEO of Health Care Global (HCG), an Indian cancer care delivery system, created a long-term bundle of care for a long-term disease (3,4). HCG’s bundle contains comprehensive diagnostics and therapy, including pathology, surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, and routine follow-up at regular intervals for up to five years.

HCG’s focus on one disease simplified the development of an innovative hub and spoke business model configuration. The hub contains the expensive radiation and surgical equipment often required during the course of treatment. In turn, community-based spokes provide patients with easier access to less capital-intensive chemotherapy and rehabilitation services, referring patients when needed to the hub.

In the HCG model, pricing of hub services varies by time of day. This approach drives round-the-clock utilization of expensive capital equipment, reducing average costs for this service. Accountability at HCG is supported by a home grown IT system (5). Although it is a for-profit organization, HCG sets aside 20% of its profits to subsidize poorer patients.

HCG’s low cost, high quality cancer care disseminated rapidly in India. HCG also entered three African countries – Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania — again with low-cost models that used telemedicine from India to leverage HCG’s scale.

2. Behaviorally-Sound Wellness Incentives: Discovery Insurance (South Africa)

South Africa’s Discovery Insurance company, established in 1992 (6), provides a blue print for an insurance program that controls costs by maintaining and improving health status through behavioral interventions (7-10).

Discovery established its Vitality program on a system of reward points – incentives that patients achieve by following a personally customized wellness program based on their behavioral, age, and health profile. The incentives were designed by a team of psychologists and behavioral economists (11).

The firm posited that 10% of health care costs are driven by modifiable lifestyle choices. Studies commissioned by Discovery indicated it achieved 10%-15% lower costs for active participants in its programs along with gains from redirecting the costs of chronic diseases (12). Like HCG, lower-income participants receive discounts and financial support at Discovery.

Vitality’s parent firm, Discovery Group, grew from an initial capitalization of $2 million to $4.7 billion of organic growth in its home market. Based on its success in South Africa, Vitality then grew globally: it entered the U.S. market in a joint-venture with the health insurer Humana in 2011 (13) and, in 2015, with life insurer John Hancock (14); in 2004, it formed a joint venture in England with Prudential UK (15); and, in 2012, Discovery introduced Vitality to China through a joint-venture with Ping An, a major Chinese financial services firm (16).

3. High-Touch Dental Care and Long Term Insurance: OdontoPrev (Brazil)

OdontoPrev, Brazil’s most trusted brand in dental care, offers more than 100 plans, many of them for a three year term (17). Since inception, the company rewarded practitioners who invested in initial preventive care. This practice helps reduce the incidence of dental disease and so both improves patient health and controls costs. The strategy yielded lower profit margins in the first year of a contract but generated longer-term financial strength. OdontoPrev thus controlled the long-term cost of care while achieving important public health goals.

OdontoPrev decided early on to focus on providing only customized dental benefits and avoiding the cross selling of medical benefits plans. The focus enabled development of a proprietary IT platform and high-touch customer service. The company’s asset-light model avoided ownership and operation of dental clinics, but, instead, focused on scaling its network of dentists.

OdontoPrev became the most trusted brand in dentistry and one of the 50 most valuable brands in Brazil. In testimony, the company enjoyed the highest renewal rate in the market.

In 2009, OdontoPrev entered the broader Latin American market through a joint venture with the Iké group, a provider of services to insurance companies in Mexico, Argentina, Venezuela, Colombia, and Brazil. The partnership marked the start of the largest dental benefits company in Latin America (18).

4. Health Care Vertical Integration: Amil (Brazil), La Ribera (Spain), and Acibadem (Turkey)

Amil: Brazil’s vertically integrated delivery and insurer, Amil, is a model so attractive that U.S. based United Healthcare purchased a majority share in 2012 for $4.9 billion (19).

Amil differs from most U.S. vertically integrated delivery systems in its governance. Amil was founded and was majority-owned by a physician entrepreneur, whose goal was to create an efficient, high quality system of care, rather than by a hospital system concerned about maintaining its occupancy rate. This focus freed Amil to organize itself with three levels of care differentiated by the severity of the patients’ needs, rather than by the site of care (20).

Amil assigns patients to the appropriate level of physician for their care. Financial incentives are aligned: primary care is provided by a network of independent physicians under a fee-for-service model, while the most complex care is provided by salaried physicians. Physicians working within the different levels have different payment models, designed to generate competition by performance on a regional, facility, and specialization basis.

The differentiation of care structure enabled Amil to create insurance plans tailored to the patients’ needs and to perform intelligent underwriting. A homegrown IT system supports communication and performance measurement.

La Ribera: The La Ribera health department in Valencia, Spain, provides integrated, population–based health for its region through an innovative public-private partnership (21). The result is a model notable for achieving high quality health care at 25% lower cost than regional public hospitals (22). In 2013, La Ribera’s global patient satisfaction index was 9.1 out of 10 (22), and it ranked first in performance among all 24 Valencian health facilities (21). In 2015, the hospital was awarded ‘Best in Class’ in Spain by Medical Gazette and Rey Juan Carlos University (23).

The Valencian government pays an annual fixed and pre-established amount for every inhabitant, adjusted annually for changes in health care costs and inflation. Like the U.S. population-based health model, La Ribera is responsible for the health care of all patients, regardless of where they are treated. For example, it is reimbursed only 80% of the cost of patients treated in other regions.

La Ribera’s model is based on four pillars: Public financing, public control, public ownership, and private management.

To account for “public control’ of quality, a government-appointed Commissioner is based at the hospital.

The ‘public ownership’ pillar required all equipment to be returned to the Valencian health ministry at the end of the contract.

The ‘private management’ pillar caused the most debate. For-profit La Ribera faced the challenge of attracting patients — who are fiercely protective of the public health system — while also meeting tighter budget constraints than its competition. In response, La Ribera adopted patient-oriented policies, including the absence of a gate-keeping function; hospital room features such as companion beds; flexible opening hours; and shorter waiting times for elective surgery and outpatient visits than the Spanish average.

To attain quality and efficiency, La Ribera implemented integrated clinical pathways to identify where and how patients should be treated. Hospital physicians visited primary care centers weekly to transmit best practices and assist with the adoption of new clinical pathways, thus freeing them to focus on more complex cases in their practices.

By 2015, the model had expanded to three additional hospitals in Valencia. At the same time, though, a low operating margin of 1% created the challenge of sustaining interest from private health care providers.

The for-profit model also encountered national political resistance. In 2014, after awarding contracts for the management of six hospitals to three private providers — including Ribera Salud — Madrid’s regional government canceled the agreements (24). In 2015, the new socialist Valencian government announced that all privately-managed health departments would return to public management when the contracts expire in 2018 (25).

Confronted with these structural, financial, and public policy challenges, Ribera Salud looked outside Spain for growth. It found a new deep pocket partner for structural and financing support in U.S.-based Medicaid insurer Centene Corporation — a $21 billion firm. Centene, dwarfed by more than $100 billion revenue rivals such as United and Anthem and challenged by its undiversified Medicaid portfolio, acquired a 50% stake in Ribera Salud (26). For Centene, the Ribera Salud model was closely aligned with its core competencies in serving government-sponsored health care programs and providing better health outcomes to local communities at lower cost (27).

Ribera Salud used this U.S. base for additional global growth. They launched in Peru, a potential gateway to the Latin America market (28). Chile, Brazil, Colombia and Mexico, whose private health expenditures as a percentage of total health care ranged from 24% to 53% (29), are interested in the model. In 2015, Ribera Salud was among five companies chosen for a tender for a new hospital in Slovakia (30).

Acibadem Hospital Group: Launching inauspiciously in 1990 in a low-end hospital with second hand equipment in Turkey, Mehmet Ali Aydmlar, an accountant, transformed the operations of the hospital chain Acibadem (31). He established professional management systems and used his accounting background to establish business and financial transparency. Growth was driven by an opportunity to provide clinical services to a previously underserved market.

Acibadem’s culture reflected Aydmlar’s focus on detail — for instance, in its rigorous management of patient feedback. Acibadem collected customer feedback through surveys; calls to patients from its call center; in person, through the patient relations supervisors in each hospital; and via an online customer complaint system, which promised a response within three days. Customer complaints were reviewed by management in a complaint-by-complaint process that served as the platform for Acibadem’s customer engagement and service strategy. This attention to detail supported internal development of managers and leaders, with 80% of the top leadership promoted internally.

Acibadem developed additional systems for all activities, including ancillary services and project and construction management. By design, every hospital used the same style, business process, and technology. The group implemented a matrix structure, with functional unit heads reporting to both the hospital director and to the head of the functional area in the corporate office. Standardized IT platforms included a patient portal for personal health management and appointment bookings, and standardized internal reporting tools including key performance indicators that offered real-time reporting and hospital-level comparisons for managers across the network.

Growing from one physician-owned hospital, Acibadem became the largest private hospital system in Turkey. After a merger with Singapore’s Parkway-Pantai to form International Healthcare Holdings Berhad, Acibadem became the world’s second largest publically traded hospital group, after U.S. based Hospital Corporation of America (32).

Two Principles for Successful Health Care Innovation

From these case studies and other examples, we highlight two principles for successful health care innovation.

1. Choose only one of three primary opportunities for health care innovation.

Successful innovations in health care focus on one of three opportunities: consumer-facing operations (Discovery/Vitality), system integration (Acibadem, Amil, HCG, La Ribera, Odontoprev), or technology. It is exceedingly difficult to execute all three dimensions, or any two combinations, simultaneously. To illustrate the difficulty, consider the key skills of the resume of the CEO of a consumer–facing innovation versus a CEO who runs integrated care facilities. The consumer–facing CEO needs retail experience, while the integrator should have created cost effective roll-ups in her past. Moreover, neither resume – retailer nor cost cutter – contains the key skill sets for the leader of a technology-innovating firm.

2. Align your venture with the Six Factors in your political and economic environment.

The venture needs to align with the structure of the system, including sources of financing, requirements for accountability and public policy, and technology and consumer desires. In doing so, you strategies that manage interactions with both friends and foes.

Unfortunately, many current initiatives conflict with these principles. Take the Accountable Care Organization (ACO) approach in the U.S. Like many other innovation initiatives, the ACO has the laudable goals of improving patient experience, improving health, and reducing per capita cost.

ACOs, however, conflict with the two principles for success we identified in the reverse innovation case studies. For one, it is exceedingly difficult to simultaneously achieve consumer friendliness and cost-reduction via system integration. Then, too, consider the challenges ACOs face in aligning with the six factors in the environment. First, vertically integrated business models are rarely known for consumer-friendliness and face challenges in innovating new technologies and processes (33). Second, the broad scope of current initiatives complicates meaningful accountability and requires massive financing. Third, their expensive business models of owning assets and installing IT systems (some cost over a billion dollars) require such high market shares to break even that they create serious public policy anti-trust threats (34).

The innovations we discuss in this paper differ from ACO-type models across the two principles of focus and alignment, as the cancer care integrator, HCG, illustrates. HCG focuses on one goal – lowering costs. Its efficient hub and spoke model enables it to operate successfully in India, in which the financing factor requires that patients pay primarily out of their own pockets. The community–based spokes align with the consumer factor. The financing factor is further addressed by a care bundle that encompasses five years of comprehensive care for patients rather than focusing on short term surgical procedures alone. Early investments have paid off in subsequently lower costs.

HCG’s focus on one disease, rather than the entirety of the health care needs of a population, aligns with the accountability factor. HCG’s business model further reduced costs via asset-light joint ventures rather than asset-heavy M&A activity, as well as home grown, lower cost, focused IT systems that aligned with the technology factor.

HCG addressed the public policy factor in two ways: first it subsidized needy patients and, second, it drew those who could afford to pay out of the public health insurance system, thus leaving more resources for the poor.

Discussion

These case studies support optimism about innovations in health care and health more generally. They highlight the ability of entrepreneurs to bring new solutions to address pressing unmet needs. They document the scaling of these innovations both within markets and across markets.

The cases underscore the opportunity of using case studies to better understand innovation in the health sector. Case studies of innovation document an innovative business model or solution, describe the evolution of that model over time, and highlight managerial responses to the challenges faced in implementing the solution in the real world (35).

Cases that focus on innovations serve as important counter-factuals to a status quo bias in many health policy discussions. Firms and markets are not fixed solutions, but rather evolve over time based on new perceptions of value by consumers, novel integration concepts in health care financing or delivery, or through the introduction of technology–based solutions that alter traditional care delivery models.

Two aspects of the case studies we selected illustrate the value of a consistent framework in evaluating innovative business models. First, we recommend a rigorous focus on one key aspect of the core business: consumer, integrator, or technology models.

Second, the Six Factors framework asks specific questions about the alignment of an innovative venture and its environment, including the role of consumers, market structure, financing mechanisms, regulatory conditions, accountability, and the nature of technology in facilitating the innovation.

This dual approach enables understanding the context for the innovation in the local market environment as well as challenges to scaling within or across markets.

Of course, there are limitations to this methodology. It is often difficult to assess the generalizability of qualitative studies. Nevertheless, case studies can stimulate discussion and debate and lead to new insights despite these limitations.

The core message is that health care innovation has become a global phenomenon, offering opportunities for adopting new models within and across countries. In the face of the enormous challenges facing the sector, innovative global business models present significant opportunities for novel solutions to diffuse, benefiting by following the principles of focus and alignment that we discuss in this article.

References

(1) Richman BD, Udayakumar K, Mitchell W, Schulman KA. Lessons from India in organizational innovation: a tale of two heart hospitals.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2008 Sep-Oct;27(5):1260-70.

(2) Herzlinger Regina E. “Innovating in Health Care – Framework.” Harvard Business School Case 9-314-017, July 8. 2015.

(3) Herzlinger, Regina E., Amit Ghorawat, Meera Krishnan, and Naiyya Saggi. “Hub and Spoke, Healthcare Global, and Additional Focused Factory Models for Cancer Care.” Harvard Business School Case No. 313-030, August 2012, (Revised August 2015).

(4) Herzlinger RE, Schleicher SM, Mullangi S. Health Care Delivery Innovations That Integrate Care? Yes! But Integrating What? JAMA. 2016; 315(11):1109-1110.

(5) Ajaikumar BS, Gopinath KS, Srinath BS, at al. “Disease-free survival pattern in breast cancer patients in India treated in a single institution.” J Clin Oncol 30, 2012 (suppl; abstr e12030).

(6) Herzlinger, Regina E. “The Vitality Group: Paying for Self-Care.” Harvard Business School Case No. 310-071, February 2010. (Harvard Business School Publishing, Revised March 2014).

(7) Baicker, Katherine, David Cutler, and Zirui Song. “Workplace wellness programs can generate savings.” Health Affairs 29, no. 2 (2010): 304-311.

(8) Berry, Leonard and Mirabito, Ann M. and Baun, William B. “What’s the Hard Return on Employee Wellness Programs?” Harvard Business Review, December 2010.

(9) Naydeck, Barbara L., Janine A. Pearson, Ronald J. Ozminkowski, Brian T. Day, and Ron Z. Goetzel. “The impact of the highmark employee wellness programs on 4-year healthcare costs.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 50, no. 2 (2008): 146-156.

(10) Halpern SD, French B, Small DS, Saulsgiver K, Harhay MO, Audrain-McGovern J, Loewenstein G, Brennan TA, Asch DA, Volpp KG. Randomized trial of four financial-incentive programs for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2015 May 28;372(22):2108-17.

(11) Vitality Group website, “Vitality History,” http://www.thevitalitygroup.com/company/, accessed March 18, 2016.

(12) D. Patel, E.V. Lambert, R. da Silva, et al., The association between medical costs and participation in the Vitality health promotion among 948,974 members of a South African health insurance company. American Journal of Health Promotion, January/February 2010. 24(3): 199-204.

(13) http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20110221006121/en/Humana-Offer-Industry-Leading-Vitality-Wellness-Loyalty-Program (Accessed June 20, 2016).

(14) “John Hancock Introduces a Whole New Approach to Life Insurance in the U.S. That Rewards Customers for Healthy Living,” John Hancock website, April 8, 2015. http://www.johnhancock.com/about/news_details.php?fn=apr0815-text&yr=2015, accessed May 31, 2016.

(15) http://discovery-holdings-ltd.mynewsdesk.com/pressreleases/discovery-acquires-full-ownership-of-its-uk-joint-venture-uk-businesses-rebranded-1081644 (Accessed June 20, 2016)

(16) Nick Hedley, Discovery takes its Vitality model to China, BIZCOMMUNITY, May 22, 2012, http://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/320/75528.html, accessed May 31, 2016.

(17) Herzlinger, Regina E., Matthew Lingenbring, Joshua Turnbull, and Ricardo Reisen De Pinho. “OdontoPrev.” HBS Case No. 314-038, September 2013. (Harvard Business School Publishing, Revised May 2014).

(18) Odontoprev gives first step towards internationalization, Exame.com, May 28, 2009, http://exame.abril.com.br/negocios/noticias/odontoprev-primeiro-passo-internacionalizacao-473568, accessed May 31, 2016.

(19) Caroline Humer, UnitedHealth to buy most of Brazil’s Amil for $4.9 billion, Reuters, October 8, 2012, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-unitedhealth-takeover-amil-idUSBRE8970E120121008, accessed May 31, 2012.

(20) Herzlinger, Regina E., and Ricardo Reisen de Pinho. “Amil and the Health Care System in Brazil.” Harvard Business School Case 312-029, August 2011. (Harvard Business School Publishing, Revised July 2014).

(21) Herzlinger RE, Moloney E, Beyersdorfer D. “La Ribera Health Department.” Harvard Business School Case 9-315-006, September 2014.

(22) NHS European Office. The search for low-cost integrated healthcare. The Alzira model-from the Region of Valencia. NHS Confederation 12-14-2011. (Accessed at http://www.nhsconfed.org/resources/2011/12/the-search-for-low-cost-integrated-healthcare, June 20, 2011).

(23) http://www.hospital-ribera.com/noticias/ver_noticia.php?destino=4&id=788# (Accessed June 20, 2016).

(24) European Union. EXPERT PANEL ON EFFECTIVE WAYS OF INVESTING IN HEALTH

(EXPH). Health and Economic Analysis for an Evaluation of the Public Private Partnerships in Health Care Delivery across Europe. 27 February 2014 (https://eupha.org/repository/sections/hsr/003_assessmentstudyppp_en.pdf accessed June 20, 2016)

(25) http://www.elmundo.es/comunidad-valenciana/2016/02/02/56afb50be2704ef6408b4593.html

(26) “Centene Corporation Purchases A Noncontrolling Interest In Spanish Health Management Group,” PR Newswire (U.S.), April 7, 2014, via Factiva, accessed January 2016.

(27) Liss, Samantha, “Nation’s largest insurers knock Obamacare marketplaces, but Centene finds success,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 28, 2016, via Factiva, accessed March 2016.

(28) “Ribera Salud asume la pérdida de Alzira en 2018 y buscará crecer fuera de España; La concesionaria ya trabaja con la hipótesis de la no renovación del contrato y descarta la creación de nuevos hospitales en la Comunitat Valenciana y Madrid bajo gestión privada – Perú y Eslovaquia son los países en los que ya tiene proyectos en marcha; Sanidad,” El Mercantil Valenciano, July 2, 2015, via Factiva, accessed January 2016

(29) World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory data repository, http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.75?lang=en, accessed June 14, 2016

(30) M. Brain, “Slovakia: Ministry chooses five consortia for further bids in hospital tender,” Esmerk Eastern European News, July 29, 2015.

(31) Herzlinger Regina E., Esel Cekin, Natalie Kindred, Gamze Yucaoglu, Michael Chu. “Acibadem Healthcare Group,” Harvard Business School Case N9-315-120, December 2015.

(32) http://www.ihhhealthcare.com/hospital-portfolio.php. Accessed June 12, 2016.

(33) Huesch, Marco, Douglas, Pamela, Schulman, Kevin, 2014 “Could Accountable Care Organizations Stifle Physician Learning and Innovation?” Health Management, Policy and Innovation, 2 (1): 18-28

(34 ) Regina E. Herzlinger, D.B.A., Barak D. Richman, J.D., Ph.D., and Kevin A. Schulman, M.D. Market-Based Solutions to Antitrust Threats — The Rejection of the Partners Settlement.

N Engl J Med 2015; 372:1287-1289.

(35) Herzlinger R, Ramaswamy VK, Schulman KA. Bridging health care’s innovation-education gap. Harv Bus Rev. 2014 Nov 11. https://hbr.org/2014/11/bridging-health-cares-innovation-education-gap.