Angela Botiba, DivineMercy Bakare, and Erika Schlosser, Carlson School of Management, School of Public Health, Medical School, University of Minnesota

Contact: botib001@umn.edu

Abstract

What is the message? Amidst a global shortfall in healthcare workers, compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic and civil unrest, GoodHealth, a community hospital, grapples with significant staffing shortages, workplace safety concerns, and financial constraints. These challenges resonate beyond GoodHealth, but are reflective of broader issues confronting healthcare organizations. This report underscores the urgent imperative for GoodHealth to implement immediate to long-term strategies to mitigate workforce shortages and cultivate a sustainable healthcare workforce. Our proposed recommendations recognize the distinct challenges faced by nursing and patient support staff, addressing their specific pain points. Additionally, we aim to develop recommendations that encompass both monetary and non-monetary needs, ensuring a comprehensive approach to workforce management.

What is the evidence? GoodHealth, like many hospitals nationwide, has historically employed broad strategies without specifically targeting the unique needs of different groups of workers. To inform our recommendations, we consulted national and international experts specializing in the economics of the healthcare workforce, organization of healthcare services, and quality of healthcare, alongside leaders of labor unions. This helped us understand past trends and identify innovative, widely implemented approaches.

Acknowledgements: The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to their faculty advisors Drs. Michael Finch and Stephen Parente whose collaboration, dedication, and expertise were integral to the completion and success of the team at the 2024 BAHM Global Case Competition.

Special appreciation is also extended to the Medical Industry Leadership Institute (including staff, executives in residence, and alumni) at the Carlson School of Management; the faculty members at the School of Public Health; as well as the invaluable input from state, national, and international experts. Their collective contributions have enriched the depth and nuance of the team’s analysis and recommendations.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The analysis presented in this paper is based on our interpretation of publicly available information and data. The authors would like to clarify that the majority of the data utilized in this analysis was sourced from publicly accessible sources, and not from internal information provided by the organization under study. While the authors have made efforts to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information presented, they cannot guarantee its completeness or absolute accuracy.

Background

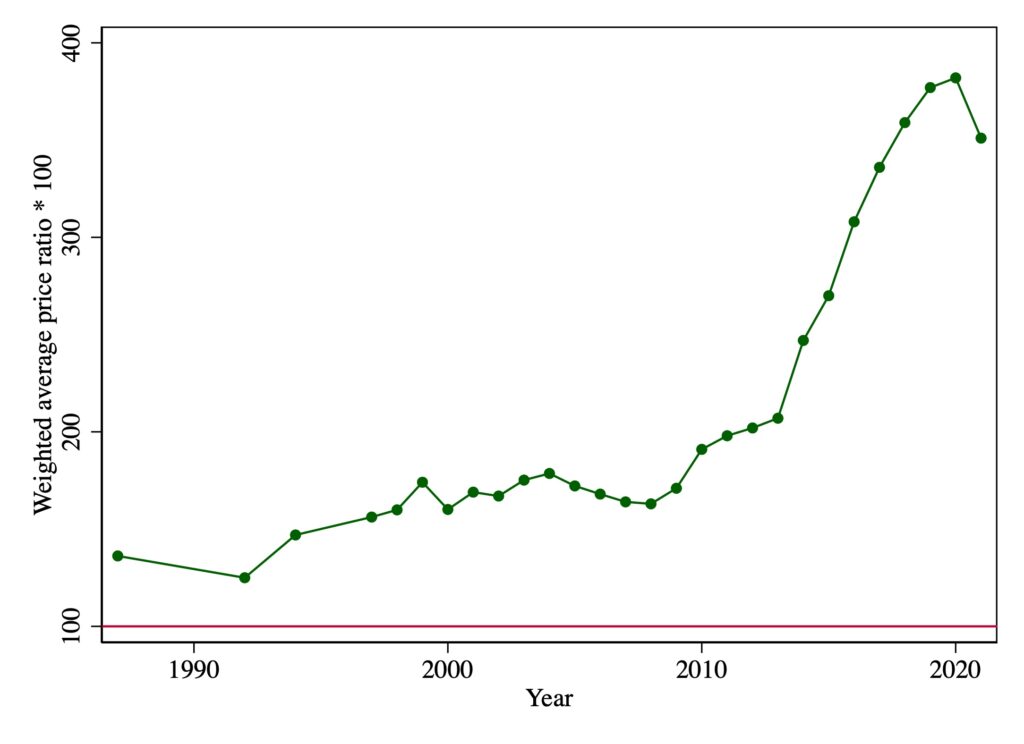

Healthcare workers are essential in the functioning of health systems, which face a significant shortfall in the healthcare workforce. The World Health Organization (WHO) projects a deficit of 10 million health workers by 2030 in low- and middle-income countries, while industrialized nations grapple with workforce shortages [1]. The critical role of labor expenses cannot be overstated, as highlighted by the challenges revealed by the nationwide labor shortage; hospitals like GoodHealth have had to lean heavily on contract labor, which has resulted in a staggering 258% increase in total contract labor expense between 2019 and 2022 [2]. More than that, in recent industry reports, the pressing issue of healthcare workforce shortages and employee turnover continues to grab attention. A 2023 Guidehouse report underscored the implications of worker turnover that, beyond mere financial costs, lead to adverse effects on workers’ well-being and patient care outcomes [3].

GoodHealth, a community hospital in a Midwest city, and similar healthcare organizations have used supplemental staffing from outside agencies to mitigate shortages, but the financial strain associated with such measures, coupled with concerns about compromised quality of care, has led them to reassess this approach. The COVID-19 pandemic created further challenges, with workforce protection and occupational hazards emerging as significant concerns. Increased workloads, workplace violence, and burnout are exacerbating the staffing crisis. This report delves into GoodHealth’s challenges, focusing on nurses and patient support staff, and provides insights and recommendations essential for the hospital’s ability to meet community healthcare needs within its financial constraints.

Current Context of the Healthcare Workforce at GoodHealth

In the face of unprecedented challenges, GoodHealth, a county-owned public healthcare organization in a bustling Midwest downtown, confronts significant hurdles in recruiting and retaining healthcare professionals. Over the years, GoodHealth has benefited from its strong engagement with the community, treating patients with complex needs and the uninsured to building relationships with community leaders to address health inequities; this has led to a strong sense of purpose and commitment among staff more likely to stay and contribute during challenging times. However, the confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic, events surrounding racial justice, and a fiercely competitive job market have amplified the difficulties in staffing the organization adequately. Particularly acute is the scarcity of nursing staff and patient support staff such as medical assistants and nurse aides who assist with tasks such as scheduling appointments, taking vital signs, and monitoring patients, with the organization contending with 520 open positions as of Fall 2023. When considering the critical needs of GoodHealth, it’s essential to understand the distinct motivations and pain points of nursing and patient support staff. Nurses, facing a high risk of leaving the bedside for other organizations offering flexibility, prioritize feeling valued, respected, and supported by their employer. In contrast, patient support staff, at risk of leaving the healthcare industry entirely, seek career advancement opportunities, which may be found outside of healthcare [4]. Recognizing these differences is crucial for tailoring strategies to effectively recruit and retain these vital healthcare professionals.

GoodHealth’s operational landscape is characterized by its role as a 400-bed community hospital, serving as both an academic medical center and a Level 1 Trauma Center. As a standard bearer of the healthcare model, GoodHealth embodies the challenges faced by 84% of U.S. hospitals in the community hospital category [5], meaning it is non-federally funded and provides services to the local population. GoodHealth’s added capacity as a county hospital provides its employees with a state-specific retirement plan. Financially, the organization grapples with substantial reliance on Medicare and Medicaid for patient revenue, compounded by high operating expenses and pension obligations. Despite holding a Disproportionate Share Hospital status for additional funding, GoodHealth’s operating expenses have consistently outpaced its operating revenues since 2019 [6]. The organization also experienced, between 2020 and 2022, a 123% increase in premium and contract labor costs to help fill gaps left by persisting labor shortages, thus contributing to overall increased labor expenses. Within this context, shortages in nursing and patient support staff pose significant challenges for the organization. Factors contributing to the scarcity of healthcare workers include increasing safety concerns, both psychological and physical, associated with healthcare roles. High levels of stress, burnout, and exposure to infectious diseases contribute to the challenging nature of these professions, deterring potential workers and exacerbating existing shortages.

Prior Strategies

GoodHealth has employed various strategies to tackle labor challenges, including reducing reliance on temporary staff and travel nursing by utilizing technology like ShiftMed for streamlined hiring [7]. Despite investing over $225 million in outpatient clinics to attract downtown workers, parking issues hinder recruitment. Homegrown initiatives like the five-week nursing assistant training and Health Care Assistant (HCA) program have seen success but have yet to address shortages fully. The HR team collaborates with marketing to enhance recruitment efforts, and retention initiatives include emotional and financial support, onsite childcare, and assistance with student loans. However, adopting temporary fixes without addressing core issues proves unsustainable. A paradigm shift is needed in workload management and workplace culture to foster a resilient healthcare workforce.

Potential Threats

While GoodHealth has implemented innovative strategies to bolster recruitment, retention, and productivity, workforce gaps persist due to many internal and external challenges. Internally, pandemic-related disruptions and healthcare worker burnout have strained the availability and well-being of HCWs. Additionally, financial losses and internal conflicts, such as a lack of transparency and inadequate response to violence against healthcare workers, have further exacerbated staffing shortages. While this is not a unique scenario for hospitals, GoodHealth nurses reported in 2021 an increased level of violence against nurses attributed to understaffing (200% increase in a single unit), which has led to concerns about patient safety and outcomes [8]. Financially, the organization contends with rising expenses related to salaries, benefits, and contract labor costs, exacerbated by a patient population largely reliant on government payers and uninsured individuals. This reliance leads to high charity care and bad debt write-offs. Operationally, staffing challenges prompt compensation, safety, and retention concerns, leading to increased union activity and a trend of employees leaving the healthcare industry for better opportunities.

Presence of Unions

The presence of unions at GoodHealth introduces a complex and challenging dynamic that reverberates across various facets of the organization, notably impacting recruitment, retention, and staff utilization. With six active unions and 60% of the workforce unionized and operating under distinct contracts and requirements, the workforce at GoodHealth is subject to a set of intricacies that extend throughout the organization.For its healthcare delivery workforce, GoodHealth has a rich history of unionization efforts with the State Nurses Association and AFSCME playing crucial roles in championing the rights of frontline workers. In 2005, over 1,000 Registered Nurses employed at GoodHealth chose to be represented by the State Nurses Association; this was one of the largest union-organizing victories in recent years [9]. All nurses are still unionized. AFSCME represents over 1,000 medical assistants, pharmacy techs, nurse-licensed practicals, and other job titles at GoodHealth [10].

In addition to affecting organizational dynamics, unions at GoodHealth introduce obstacles due to increased union activity, exacerbating tensions between employees and leaders. As the organization faces financial strains, proposed budgetary cuts to employee health benefits have sparked dissatisfaction among employees, leading to a vote of “no confidence” in the CEO and subsequent executive resignations [11]. Previous instances of employee dissatisfaction, such as picketing over staffing levels and retention concerns, further underscore the challenges in achieving cohesion between employees and executive leadership.

Recommendations

Our recommendations for GoodHealth are structured on strategies aimed at increasing the retention of current employees, recruiting new employees to fill in the current gap, and creating a sustainable pipeline of workers. The goal of these strategies is to market GoodHealth as a desirable employer in the state and to ensure that GoodHealth attracts and retains full-time employees and eventually eliminates the need for high-premium contract labor.

Community hospitals like GoodHealth often face significant challenges influenced by the county board’s oversight, budget constraints, resource allocation, and union dynamics. The county board’s decisions regarding funding allocation and policy directives can significantly impact the hospital’s ability to implement workforce strategies, particularly when faced with limited financial resources. Budget constraints further exacerbate these challenges, often forcing hospitals to prioritize essential services over workforce development initiatives. Additionally, navigating union dynamics presents a complex landscape, as unions may support and resist changes depending on their perceived impact on workers’ interests and collective bargaining rights. Balancing the competing demands of stakeholders while effectively allocating resources becomes crucial in addressing workforce challenges and ensuring the delivery of high-quality patient care at GoodHealth.

Short-Term Recommendations

Due to the state of the healthcare shortage at GoodHealth, it is paramount that some strategies be urgently employed to curb the bleeding and retain the current staff. We have created four short-term recommendations to help increase the staffing levels at GoodHealth. These include encouraging leadership engagement with the workforce, creating an employee harm index, constructing a wellness champion program, and implementing differential pay. These short-term initiatives will require little to no funding in the first year of implementation.

Leadership Engagement

There is a history of mistrust of leadership at GoodHealth between employees and executive leaders. Nurses have expressed distrust in the CEO’s decisions, particularly those affecting patients and driving caregivers away from the bedside [12]. We recommend increasing leadership engagement with the healthcare workforce to address this issue. Accessibility and transparency should be at the forefront of GoodHealth’s leaders. To communicate this, we recommend that leaders conduct walkabouts/rounds and host monthly calls to create meaningful connections and understand the needs of their healthcare workers. Along with the walkabout, we recommend a monthly town hall or a standing virtual meeting for leaders to communicate organizational changes and for healthcare workers to voice their concerns. Trust is a cornerstone of transparency. Encouraging a two-way conversation between the leaders of GoodHealth and the healthcare workers will promote trust, responsiveness, and shared responsibility.

Employee Harm Index

Violence against healthcare workers is a pressing issue leading to physical and emotional harm. This phenomenon has contributed, in part, to the departure of healthcare workers from the field. Recognizing the urgency of this issue, we recommend that GoodHealth create an Employee Harm Index (EHI). This platform will provide a mechanism for healthcare workers to report incidents of physical and verbal violence against them. The EHI will serve as a real-time tracking system and be analyzed every month to provide insight into the frequency, nature, and location of violence against healthcare workers. Information from the EHI will be used to quickly implement targeted interventions and measures to ensure the safety of the healthcare workers. The EHI will empower healthcare workers and represent a proactive approach to tackling workplace violence and preventing harm before it escalates.

Wellness Champion

The current healthcare worker shortage is both a result of and a contributor to burnout. Nurses and patient support staff often face heavy workloads, long hours, and regularly witness traumatic events and may experience secondary trauma or compassion fatigue when dealing with patients’ critical situations. Thus organizations like GoodHealth must implement wellness initiatives that address these issues. The Wellness Champion initiative aims to acknowledge the challenges related to burnout and foster a culture of well-being in the hospital. Healthcare workers will nominate their colleagues as Wellness Champions, individuals who will serve as point persons to assess mental well-being. These individuals will communicate wellness initiatives, motivate and encourage their colleagues to participate in wellness programs, and plan events to improve mental well-being.

The needs of healthcare workers are evolving, and no one understands this better than a colleague. To ensure the program’s feasibility, an annual discretionary budget of $100,000 will be reserved for any projects that need funding. The Emergency Department will be the first department to undergo this initiative. The program’s efficacy will be evaluated over three months, and based on the data collected and initial feedback, the program will be expanded to other departments at GoodHealth. Wellness Champion initiatives have been employed at various institutions since 2000 and have been shown to reduce healthcare costs and increase employee productivity [13].

Differential Pay

At GoodHealth, healthcare workers are currently working understaffed shifts with inadequate support leading to an increased workload. The increased workload is a major contributor to the burnout many healthcare providers feel and may be a factor in the large number of workers looking to leave the industry. To help with the retention efforts of employees at GoodHealth, we recommend the implementation of short-term differential pay for staff working understaffed shifts. This strategy acknowledges the current situation and compensates healthcare providers for the additional workload [14]. It also signals that GoodHealth is committed to rectifying the issue. The increased wages will further incentivize the institution to work harder to ensure that healthcare workers don’t continue working understaffed shifts, as it will affect operating expenses. The decision to increase compensation will depend on various factors, including improvements to the organization’s financial health (e.g. phasing out costly contract labor), and continued subsidies provided by the County.

Union Impacts

While the recommendations above strive to increase healthcare worker retention at GoodHealth, the unions will have to be active in the initiation. Most local unions have established or are actively working on incorporating differential pay in their contracts, and thus, the differential pay discussed above will only apply to non-unionized workers. The unions will favorably receive the implementation of the EHI and wellness champion initiative as it is designed to improve workplace safety and reduce violence against healthcare workers. GoodHealth must collaborate with the unions representing their healthcare workforce to ensure these initiatives are genuinely in the best interest of their employees. The success of these initiatives relies on the unions’ buy-in, which can help refine and promote them with the healthcare workers.

Mid-Term Recommendations

Ever since the pandemic, employees have been increasingly looking for more ways to bring flexibility into their work. There are three different flexible staffing structures that we recommend GoodHealth implement to address these flexibility requests, especially for those in nursing and support roles. These recommendations include the Baylor Shift, staffing at “top-of-license” and creating an apprenticeship.

Implementation of Baylor Shift

The first flexible structure is called “The Baylor Shift”. This staffing structure was created by Baylor University Medical Center in the 1980s to help with weekend staffing shortages and improve the work-life balance of employees [15]. The objective of this structure is to allow nurses to take two 12-hour weekend shifts a week, instead of the standard 36-hours per week nursing schedule, and still be considered full-time employees while receiving full compensation and benefits. The Baylor Shift would allow for a significant increase in flexibility for nurses. This would help GoodHealth fill specifically difficult shifts such as the weekend shift.

The implementation of this program would consist of three different phases. The first phase would involve the creation of the program, understanding the specifics of this organization, along with the recruitment of employees into the program. With the launch of a new program, one of the first and most important parts is to educate the population about the new opportunity.

Staffing at “Top-of-License” and Education

The next staffing structure recommendation we have is to staff employees in “top-of-license” roles. Staffing clinicians in “top-of-license” roles is a strategic approach that maximizes the utilization of healthcare professionals’ skills and expertise [16]. This model involves assigning tasks and responsibilities to clinicians that align with their highest level of education, training, and qualifications. By ensuring that clinicians focus on activities that uniquely require their advanced medical knowledge, decision-making abilities, and clinical expertise, healthcare organizations can optimize efficiency and enhance patient care. Staffing clinicians in “top-of-license” roles not only allows healthcare providers to operate at their full potential but also contributes to a more collaborative and integrated healthcare delivery system. The refinements of the program should continue over the next year to ensure that it is a suitable and sustainable action for the organization.

The adoption of a “top-of-license” staffing approach emerges as a strategic initiative for GoodHealth to maximize the skills of healthcare professionals while optimizing patient care. This model recognizes the diverse expertise within the healthcare team, fostering collaboration and a balanced distribution of responsibilities. When employees are practicing at their “top-of-license”, productivity and staff satisfaction increase, and providers end up having more time to spend with their patients [17].

Apprenticeship Program

The last structure implementation would be the creation of an apprenticeship program with local universities. As the seasons change, so do the needs of the employees. For example, when summertime comes around, kids will typically go on school break and the needs of some employees will change. In addition, during the summer months, many employees want to use their hard-earned benefits to enjoy time off. Our proposed solution would offer increased flexibility to those whose needs have changed during specific times of the year, especially targeting the summer months. We would look to partner with local universities close to GoodHealth’s campus to utilize the current students and create a more flexible schedule for employees. This partnership would target students who are interested in pursuing a career in the healthcare field or are already in a health professions program such as nursing.

Union Impacts

With all of the staffing structure recommendations discussed above, it is imperative to also discuss the impact that unions may have on these recommendations. After discussions with GoodHealth’s HR team, it became clear that unions have a significant impact on the ability to change staffing structure and utilization. For these recommendations to work, GoodHealth needs to create strong relationships with union representatives and be sure to include them in the creation of these programs. Allowing each union to have a voice in the creation and implementation of these programs is essential to the success they produce. The support from unions is especially important in the adjustment of staffing structures and needs to be highly considered when implementing new staffing programs.

Long-Term Recommendations

Our final set of recommendations has a long-term range and is focused primarily – not exclusively – on building the talent pipeline of the workforce of the future. These recommendations address career mobility, collaboration, and management of workload through cross-functional collaboration and the injection of flexibility into how care can be delivered.

Recruiting Universal Workers

Our first recommendation to build up the talent pipeline is to recruit and prepare universal workers for a career at GoodHealth. By adopting a universal healthcare worker strategy, GoodHealth can tap into a pool of unusual profiles of workers and introduce them to a hospital setting. The state GoodHealth is located in is home to a large population of foreign-born workers who primarily work in home health or long-term care facilities. These workers are primarily compensated through Medicaid. As an illustration in Washington State, personal care aides are mandated to undergo 75 hours of entry-level training along with 12 hours of ongoing education. This training closely aligns with the training prerequisites set at the federal level for certified nursing assistants and home health aides [18]. This would require establishing clear training standards based on competencies to prepare individuals for roles as “universal workers” across various care settings.

Implementation of Interdisciplinary Teams

The implementation of interdisciplinary teams has emerged as a transformative approach, bridging diverse fields to provide holistic and patient-centered care [19]. This innovative program leverages the collective expertise of professionals from various disciplines, such as physicians, nurses, social workers, and therapists, to collaboratively address complex healthcare challenges. Through seamless communication and shared decision-making, these interdisciplinary teams foster a comprehensive understanding of patients’ needs, considering both medical and non-medical factors [20]. This synergistic approach not only enhances the quality of care but also promotes efficiency in diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management.

Career Lattice Pathways

The next long-term recommendation for GoodHealth is to encourage workers to identify their desired career goals and provide assistance to them in helping meet them. This recommendation encourages a flexible and dynamic approach to career progression, allowing and encouraging employees to navigate diverse paths within the organization [21]. This recommendation would require a meeting and discussion with the union leaders to help create a program that is suitable for the employees and their contracts. It also requires GoodHealth to encourage regular career conversations between employees and supervisors looking to identify individual strengths, interests, and aspirations. In addition to providing career counseling and encouragement, GoodHealth should provide resources such as training programs, mentorship opportunities, and skill-building initiatives to support employees in acquiring the necessary competencies for their chosen career lattice paths.

Virtual Clinical Platforms

The last recommendation for GoodHealth involves the implementation of virtual clinical platforms to introduce flexibility into the roles of nurses, allied health professionals, and patient support staff. This initiative aims to leverage technology to create virtual environments where healthcare professionals can conduct certain clinical and administrative tasks remotely, allowing for a more flexible work arrangement. By utilizing virtual clinical platforms, GoodHealth can address challenges related to scheduling constraints and flexibility in work hours [22]. The implementation will require enlisting a consulting firm like Deloitte or Accenture that focuses on technological implementation to help the organization evaluate current workflows and identify the best platform to fit GoodHealth’s workflow.

Union Impacts

The impact of unions on the recommended strategies for building GoodHealth’s talent pipeline would likely be multifaceted. The recruitment of universal workers might find support from unions, especially if they perceive it as a means to expand employment opportunities for their members. The unions could play a pivotal role in identifying core competencies and collaborating with health organizations to ensure their members are adequately prepared for roles in hospitals. The implementation of interdisciplinary teams might also receive backing from unions, as it aligns with the ethos of promoting worker collaboration and inclusivity.

Financial Analysis

For more details, please refer to Table 1.

Cost Savings

The basis of our financial analysis to generate additional funds to allocate to our proposed solutions lies in phasing out contract labor and savings generated from increased retention rates.

Transition away from Contract Labor

The potential for significant cost savings lies at the heart of our proposal to phase out contract labor at GoodHealth. Two distinct approaches were employed to estimate the annual savings resulting from this initiative.

Approach 1: Using job openings/vacancies percentage

Analyzing the vacancy rate further substantiates the potential savings. We determined that in 2022, 22% of GoodHealth’s nurse workforce comprised contract nurses, totaling approximately 396 travel and temporary nurses. Travel nurse’s contracts can span anywhere from 2 to 26 weeks, depending on factors such as the travel nursing agency and facility requirements [23].

As of January 4, 2024, with 520 job openings, 24% of which were in nursing (125 positions), the projected cost of filling these positions with travel nurses was approximately $22.5 million. Conversely, using registered nurses (RNs) for the same positions would result in an estimated cost of $10.5 million. Assuming an RN FTE fills every opening, our anticipated savings is approximately $11 million. It’s important to note that these figures represent a conservative estimate, and segmenting the data by nurse pay and department could potentially yield even more significant savings. The total cost savings, therefore, range from a conservative $11 million to a more optimistic $39 million.

Approach 2: Eliminating 50% of travel nurse/temporary healthcare worker

In 2022, the annual premium and contract labor expenditure reached $71.2 million. By conservative estimates, eliminating just half of this cost by reducing travel nurses and temporary healthcare workers would yield savings of approximately $35.6 million.

Retention Savings

The average hospital turnover cost for nursing staff is between $28K and $51K, and $25-30K for frontline support staff [24]. GoodHealth currently has a retention rate of 87% across the organization; GoodHealth currently tracks retention rates globally across care settings and roles. The total number of all nurses is 1,762 671 for patient support staff at a turnover rate of 13%. Applying the top of the range, we estimated turnover costs of $11.7 million for nursing staff and $2.6 million for patient support staff for a total turnover of $14.3 million, our total turnover costs at an 87% retention rate.

If we calculate the turnover costs at 7% (93% retention rate) using the same logic, we have total turnover costs of $7.7 million. The differential is $6.6 million in turnover savings from higher retention rates.

Estimated Costs of Implementation

Short-Term Recommendations

All short-term recommendations, except for the leadership engagement initiative, involve associated costs. As leaders are expected to maintain accessibility without additional funds allocated, this initiative remains cost-free. We recommend a 12% increase in the annual rate for nurses ($40/hour) and support staff ($17/hour) to retain workers during understaffed shifts. Starting in 2025, a yearly budget of $100,000 will be allocated for the wellness program. Implementing a primary Employee Harm Index in 2024 will be followed by a standardized platform with an estimated cost of approximately $15,000.

Mid-Term Recommendations

For the Baylor shift initiative, we assume that employees who prefer this shift pattern will fill 20% of current nurse role openings. The average salary for a Baylor shift nurse is $113,000 [25]. A 10% hourly pay raise is proposed for nurses and patient support staff working weekend shifts. Additionally, we suggest an hourly pay of $20 for 30 students per 8-hour shift over 12 weeks for the Apprenticeship initiative. These mid-term expenses are proposed to be incurred starting in 2025.

Long-Term Recommendations

Long-term recommendations aim to establish a sustainable workforce pipeline at GoodHealth. Onboarding costs an average of $1400 per employee, with an additional $500 for certifications or education materials. With 50 employees in mind, we propose a budget accordingly. The Career Lattice initiative suggests transitioning 1.5% of nurses and patient support staff into new roles yearly, with a 20% salary increase. Expanding a virtual clinical platform across 30 departments in 2029 is estimated to cost $200,000. Based on GoodHealth’s 2022 financial report and benchmark values, these projections anticipate substantial cost savings of $47-105 million alongside an investment of $26 million over a 6-year plan. However, inherent limitations exist, including potential workforce fluctuations and economic shifts. GoodHealth’s leadership should remain vigilant and periodically reassess financial projections to ensure alignment with evolving dynamics.

Conclusion

Our workforce recommendations for GoodHealth form a comprehensive strategy to revitalize employee networks and ensure Healthcare workforce stability at GoodHealth by tackling immediate staffing challenges while building a robust and enduring workforce. The approach, spanning short-, mid-, and long-term initiatives, emphasizes collaborative efforts with unions and employees, ensuring alignment with organizational goals and prioritizing employee well-being. The financial analysis supports the viability of the proposed initiatives, projecting significant returns on investment for GoodHealth. Estimated cost savings, ranging from $47 million to $105 million, are carefully calculated based on phased implementation and critical assumptions. As GoodHealth adopts these recommendations, the following steps involve collaborative efforts with unions and employees. Open communication, regular feedback, and inclusive decision-making will be crucial in navigating implementation.GoodHealth is poised to redefine healthcare workforce management for a sustainable and thriving future by setting benchmarks in talent management, cost efficiency, and employee well-being.

Table 1. Financial Analysis (Values in Thousands)

Endnotes

[1] World Health Organization. Health workforce. https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-workforce#tab=tab_1. n.d.

[2] Syntellis and The American Hospital Association. 2022. https://www.syntellis.com/sites/default/files/2023-03/AHA%20Q2_Feb%202023.pdf

[3] Guidehouse. Prioritizing Well-Being in the Healthcare Workforce. 2023. https://guidehouse.com/insights/healthcare/2023/prioritizing-well-being-in-healthcare?utm_source=bambu&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=advocacy&blaid=4718445

[4] AMN. 2023 AMN Healthcare Survey of Registered Nurses. https://www.amnhealthcare.com/amn-insights/nursing/surveys/2023/. May 2023.

[5] American Hospital Association. Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals. https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals. 2024.

[6] Hennepin Healthcare System, Inc. Financial Report. https://www.hennepinhealthcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Hennepin-Healthcare-System_22-FS_Final.pdf. December 2022.

[7] Gooch K. Health Systems Create Alternatives to Contract Workers. Becker’s Hospital Review. 2023 Sep 13.

[8] Minnesota Nurses Association (MNA). 2022. https://mnnurses.org/hennepin-healthcare-nurses-report-rising-violence-against-nurses-and-patients-cite-under-staffing-unresponsive-management-as-barriers-in-new-survey/

[9] Workday Magazine. 2005.

https://workdaymagazine.org/hcmc-nurses-organize-with-mna/

[10] AFSCME. N.d. https://www.afscme2474.org/about-2474

[11] Nelson T, Krueger A. Hennepin Healthcare Nurses Picket Outside Minneapolis Hospital. MPR News. 2022 Aug 22.

[12] Minnesota Nurses Association (MNA). Hennepin Healthcare leaders resign under pressure by nurses to hold CEO accountable to workers and patients. 2024. https://mnnurses.org/hennepin-healthcare-leaders-resign-under-pressure-by-nurses-to-hold-ceo-accountable-to-workers-and-patients/

[13] Broyles D. What Employers Should Know About Shift Differential Pay. Complete Payroll Solutions. https://www.completepayrollsolutions.com/blog/shift-differential-pay. 2022 Jun 23.

[14] Weinberg A. Ensure Practice Staff Works to the Top of Their License. Physicians Practice. 2016 Apr 28.

[15] Stone R. Bryant N. Feeling Valued Because They Are Valued. LeadingAge LTSS Center @ UMass Boston. 2021 Jul.

[16] Health Carousel Nursing & Allied Health. How Long Can a Travel Nurse Stay in One Place. n.d.

[17] Stone R. Bryant N. Feeling Valued Because They Are Valued. LeadingAge LTSS Center @ UMass Boston. 2021 Jul.

[18] Salary.com. Job Posting for Nurse Weekend Warrior/Baylor Program at Edenbrook Edina. 2023 Dec 26.

[19] Rosen MA, DiazGranados D, Dietz AS, Benishek LE, Thompson D, Pronovost PJ, Weaver, SJ. Teamwork in healthcare: Key Discoveries Enabling Safer, High-quality Care. The American Psychologist. 2019 Feb 4. 73(4), 433–450.

[20] Bendowska A, Baum E. The Significance of Cooperation in Interdisciplinary Health Care Teams as Perceived by Polish Medical Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 5;20(2):954.

[21] Society for Human Resource Management. Developing Employee Career Paths and Ladders. n.d.

[22] Abernethy A, Adams L, Barrett M, Bechtel C, Brennan P, Butte A, et al. The Promise of Digital Health: Then, Now, and the Future. NAM Perspect. 2022 Jun 27. 2022:10.31478/202206e.

[23] Salary.com. Job Posting for Nurse Weekend Warrior/Baylor Program at Edenbrook Edina. 2023 Dec 26.

[24] Snyder K, Bottorff C. Key HR Statistics and Trends in 2024. Forbes Advisor. 2023 May 17.

[25] Ryzhkov A. How Much Does It Cost to Start Virtual Care? FinModelsLab. 2023 Aug 19.