Will Mitchell, Anthony S. Fell Chair in New Technologies and Commercialization, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto

Contact: Will Mitchell, william.mitchell@Rotman.Utoronto.Ca

Abstract

What is the message?

Although drug pricing is highly contentious around the world, with frequent claims of overcharging, average profitability in the pharmaceutical industry is not excessive. Companies need to achieve prices above total average costs if they are to cover the fixed costs of successful and failed development efforts. The most efficient way to accomplish the dual goal of incenting ongoing innovation while also achieving cost effectiveness and broad-based access is to price drugs at different prices in different markets, based on some combination of ability and willingness to pay.

What is the evidence?

Assessment and evaluation of current bio-pharmaceutical industry data, trends, and strategies.

Disclosure: Some of the academic health management programs that I have taught in and several of my research projects have received programmatic support from life sciences companies. This article received no financial or editorial support. All information in the article is based on public sources.

Submitted: October 1, 2018; accepted after review: October 31, 2018.

Cite as: Will Mitchell. 2018. Pharma Prices Are Not Too High (Usually). Health Management Policy and Innovation, Volume 3, Issue 2.

Drug pricing has been controversial in the U.S. and elsewhere essentially as long as drugs have been sold. In 1959-1960, the Kefauver Drug Hearings conducted by the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly concluded that pharmaceutical firms did not merit the prices they were charging; [1] moreover, as William Comanor put it in 1966, “the committee charged that little of social value came from industry laboratories”. [2] Scrolling forward to the present, in the past decade or so, prices have escalated far higher, particularly as the biological revolution has taken hold, with some drugs now having list prices in the tens and even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

With increased drug prices has come scrutiny and debate. Perhaps the only thing that the three highest profile candidates in the 2016 U.S. Presidential primaries and election – Donald J. Trump, Hillary Rodham Clinton, and Bernard Sanders – agreed on was that drug prices are far too high. Article after article in the press and media in the U.S. and other countries, as well as highly publicized Congressional hearings, have reported claims of high prices and massive price increases, sometimes targeting individual executives as responsible for price gouging. The current U.S. administration has announced an ongoing sequence of potential initiatives directed at what it believes are excessive prices. [3] And in the 2018 Gallup poll of industry reputation, the pharmaceutical industry finished 29th of 30, with a net negative rating of 23% [30% positive; 53% negative], slightly ahead of only the U.S. federal government. [4] Clearly, drug prices must be too high.

Yet what would it mean for prices to be “too high”? The simplest conceptual case would be that value received by patients and other stakeholders in the healthcare system does not justify the prices charged by pharmaceutical companies and intermediaries such as distributors, presumably because the companies have market power that allows them to price above marginal cost. Yet, as I will argue in this article, a close look at relevant data does not support this conclusion.

Instead, thoughtful assessment suggests that average profits in the pharmaceutical industry are largely in line with the companies’ needs to support ongoing development and commercialization of new drugs and related services. Although some individual cases may be questionable, the overall pattern is one of an industry that typically acts responsibly in supporting necessary business activities while seeking to provide value for patients.

I will start with the assumption that recent advances in drug therapies are making important contributions to healthcare and human health. While there are credible debates about marginal value and concerns about side effects of some drugs and, especially, which patients they might be suited to, there are undoubted major contributions in areas ranging from multiple types of cancer, to Hepatitis C, to a broad set of immunological diseases, to ophthalmic needs, to HIV/AIDS, and a host of other conditions. [5] Moreover, the companies that market these drugs also are increasingly providing a range of support such as infusion services, patient and provider education, patient financial support, nutrition and life style counselling, pay for performance contracts, and other services that provide far more encompassing value than simply a core pill or injection.

Some of these advances of drugs and complementary services serve tens of thousands of people. Others serve only a few individuals who suffer from orphan diseases. Again, while it is entirely reasonable to question whether a particular therapy suits an individual patient in a given context, the overall impact is contributing to solving real human medical needs

Rather than a single price, drugs have multiple prices

Of course, improved health by itself is not enough to end an argument about the industry. There needs to be a corresponding judgement about cost effectiveness [6], as reflected in the price that drug companies receive from the myriad types of payers. This is where the controversy arises. Yet payers, particularly third party payers such as pharmaceutical benefit management companies (PBMs) with substantial market power of their own, have substantial ability to negotiate discounts and rebates, manage formularies, and shape whether drugs achieve market access. [7]

In practice, actual prices to most payers typically are far below list prices that show up in public reports such as Average Wholesale Price (AWP), which one of my colleagues informally likes to refer to as “Ain’t What’s Paid”. Indeed, for almost all drugs, there is no one price – instead, there are multiple prices, sometimes even to the same payer, based on negotiations, public mandates, pressure from patients and patient advocates, and market conditions.

It is not my intent here to argue that any one price to any one payer is “too high” or “too low”. It is the job of any payer to negotiate a price that meets its own definition of value. And there may well be appropriate opportunities to help some payers increase their negotiating strength and sophistication, and so help the healthcare system meet the goals of cost effectiveness and broad access.

Rather, my aim is to argue that the overall revenue that drug companies receive from payers aligns with the health system’s complementary goals of creating incentives for ongoing innovation and for providing as broad access as possible to appropriate health services. Several metrics and practical conditions of the industry underlie this conclusion. In the next sections, I will discuss profitability, the need for average prices of pharmaceuticals to exceed variable costs, and the increasingly short time window for companies to recoup fixed costs of developing and bringing drugs to market before they face generic competition.

Average profitability grew through the early 2000s and then declined

Using companies’ financial statements, I have collected data on more than 70 major pharmaceutical firms that have sold branded pharmaceuticals, including long established companies and new biological entrants based in Western Europe, North America, and Japan, with data for most firms going back into the 1970s or earlier. The most complete period, 1990 to 2017, includes 33 to 50 firms per year, with the numbers varying due to consolidation. Where appropriate, I also draw data on the more than 500 public pharmaceutical and biological firms listed in the Compustat data base. This section and the discussion of costs that follow will be a bit numbers heavy, because it is necessary to use real data to provide an accurate picture of the industry and relevant trends.

The simple story of pharma profitability is that it grew and then declined. In the 1980s and early 1990s, bio-pharma firms’ median profitability based on return on sales (ROS) was about 7% to 11%, a comfortable but not particularly high rate of return. During the 2000s, with the introduction of new generations of large market drugs, median ROS grew to a maximum of 17% in 2009.

Then, between 2010 and 2017, list prices of many high profile new drugs, particularly newly-approved biologicals, increased substantially. One might expect corporate profits to have grown even higher in the past decade.

However, rather than continuing to increase, median return on sales in the industry has declined: falling to 13% to 14% in each year from 2014 to 2017 (the trends are similar if we base profitability on return on assets). Within the average, there is substantial variance. In 2017, for instance, the profitability of 33 companies with a median ROS of 13% ranged from a high of 41% (reflecting gains from the sale of a major business unit) to a low of –9% (reflecting ongoing losses at a biological specialist). In 2016, with median ROS of 14%, the maximum and minimum ranged from 45% (a win from a blockbuster biological) to –56% (the same financially struggling biological specialist as in 2017).

While some firms in some years have achieved particularly high profitability, occasionally even with ROS of 40% or higher – 1.5% of the cases among 1,193 years of observations for 61 unique firms in my data from 1990 to 2017 exceed 40% ROS; 5% exceed 30% – such cases typically last at most for a few years and fall again as competing products enter the market. Hence, even as list prices have increased, average profits in the industry have fallen.

Overall, the bio-pharma industry is now comfortably profitable on average, but far from levels that suggest massive systemic price-gouging. Indeed, major ongoing price reductions on the scale that some critics appear to believe appropriate would quickly lead to untenable financial levels for most or all firms.

Consider the simple math: if the median firm with 13% ROS in 2017 was forced to cut its net prices by 10% with no other changes to its business model, it would barely clear break even. And most of the half of its competitors with ROS below the median value would fall to break even or below. The arithmetic becomes a bit more complicated if the price cut only applied to U.S. sales, which typically mark well over 40% of a U.S. based company’s revenue (and often much higher) and lesser but still substantial proportions for European and Japanese pharma firms, but the financial impact would quickly be unsustainable. Yet a 10% price cut is well below what the debate would suggest is needed.

Cross-industry comparisons of multiple profitability metrics (e.g., return on sales, assets, capital, and equity) based on reports from the industry analyst firm CapitalIQ show that the pharmaceutical and biological industry categories tend to be somewhat more profitable on average than the S&P 500 list of the largest public firms, commonly at about the level of technology and computer hardware companies, but again well within a range of normal profitability. Why, then, have bio-pharma profits declined as list prices – and controversy about prices –have increased?

The costs of doing business have increased

I will highlight four reasons for declining profitability during the past decade: discounts, production costs, R&D expenses, and marketing expenditures. First, part of the cause for the decline in average profitability is the issue I noted earlier: list prices are largely meaningless. During the past decade, third-party payers in the U.S. have become increasingly aggressive about demanding discounts in return for agreeing to include drugs on their formularies of drugs approved for their covered lives. Particularly as competitor products enter a therapeutic class, negotiated discounts commonly increase and net prices fall.

While most discounts are confidential, reports from Kaiser Permanente, investigative journalists, and others suggest that rebates can reach 25% to 50% or more of list price. Hence, while a company with a first-to-market blockbuster may enjoy a few years of high profitability, competition and reactions by payers tend to bring it back down.

Second, many of the newer biological drugs are more expensive to produce than earlier generations of small-cell pharmaceuticals. Median “cost of goods sold” (COGS), i.e., production costs of the drugs, of two dozen major firms I am tracking has grown from about 21% in 2000 to 25% in 2017. While not a huge increase, the extra costs have been enough to affect profits.

Third, the costs of developing and obtaining new drugs have increased due to increasing need for multi-source development activities. It simply is not possible for a single company to possess all the skills needed to bring a full portfolio of drugs to market by relying solely on internal development. Instead, bio-pharma firms now employ a sophisticated set of build, borrow, and buy strategies to source new drugs, including a complex mix of internal R&D, alliances, and acquisitions.

The extent of both acquisitions and alliances has grown strikingly according to figures reported by data bases such as ReCap, Cortellis, CapitalIQ, and SDC Platinum. The annual number of M&A deals has grown from 150 to 200 in the late 1990s, to more than 500 in 2017. Some M&A deal values reach billions of dollars: Cortellis reports more than $250 billion in global bio-pharma acquisition value in each of 2016 and 2017.

Inter-firm alliances in the sector also have become increasingly common. In 1990, fewer than 350 alliances were reported in industry data bases. In 2017, depending on the data source, the reported number had grown to somewhere between 2,500 and 4,000 partnerships. While alliances tend to have lower deal value than acquisitions, annual expenditures now total multiple billions of dollars.

Internal R&D costs, meanwhile, rather than decline as acquisitions and alliances have increased, have also grown. Annual R&D expenditures by 22 major bio-pharma firms in 2000 reached about $32 billion; in 2017, the top 17 bio-pharma companies spent about $73 billion. Across the full set of publically traded bio-pharma firms reported by Compustat, R&D expenditures in 2000 and 2014 grew from $51 billion to $118 billion. In addition to sheer magnitude, R&D has also grown as a percentage of sales: among the leading firms, the average ratio grew from 15% in 2000 to 18% in 2018.

Fourth, selling, general, and administration (SG&A) expenditures also have grown, though at a slower rate than R&D. SG&A is an indicator of marketing and other commercialization activities, including the costs of patient support that are now important parts of the suite of services that complement a core drug. Compustat data for public bio-pharma firms report SG&A growth from about $150 billion in 2000 to $280 billion in 2014.

Despite the growth in magnitude, average SG&A as a percentage of sales has remained stable or even fallen; among the top 30 to 40 firms, the ratio fell from 35% in 2000 to 28% in 2017. The reduction in the marketing cost ratio reflects the shift in strategy during the period, from emphasizing large market drugs such as cardiovascular statins and gastro-intestinal proton pump inhibitors, which require large sales forces, to placing greater emphasis on products such as immuno-oncology drugs prescribed by specialist health care providers, which require more targeted commercial support. At the same time, though, the newer drugs have required substantial patient support as well as market access expenditures in negotiations with third-party payers, which limits the ability to undertake further reductions in expenditure.

The core point here is that multiple aspects of development and commercialization costs have grown more quickly than revenue during the past decade or so, despite the frequent claims of excessive price increases. The expenditures reflect the real costs of doing business in the bio-pharma sector: obtaining and creating new drugs, conducting trials, manufacturing the drugs, gaining market access, and supporting them in the market. Currently, the industry is not under a threat of failure but also is not at any obvious level of excessive profitability that would support extensive price cuts. While individual firms may enjoy very high profits for a few years, they typically return to earth; the overall profile is reasonable. In parallel, firms may suffer low or even negative profits in some years – 14% of the annual observations for the major firms in my data from 1990-2017 report losses – but typically return to reasonable levels, or are purchased by competitors who can use their resources more effectively.

Fixed costs are high, with a substantial gap between variable costs and total average costs

Now let’s leave the deep dive into data and consider the nature of costs in the industry. Bio-pharma is marked by high fixed costs in R&D, whether done internally or paid for via alliances and acquisitions. Successful projects typically require many years and many millions of dollars in lab work, clinical trials, and regulatory expenses, whether initially sourced internally or externally. And many projects fail – that is the very nature of experimentation – sometimes early in the development cycle after a few million dollars but occasionally reaching into the hundreds of millions or more if a drug proceeds to large scale Phase 3 trials before failing.

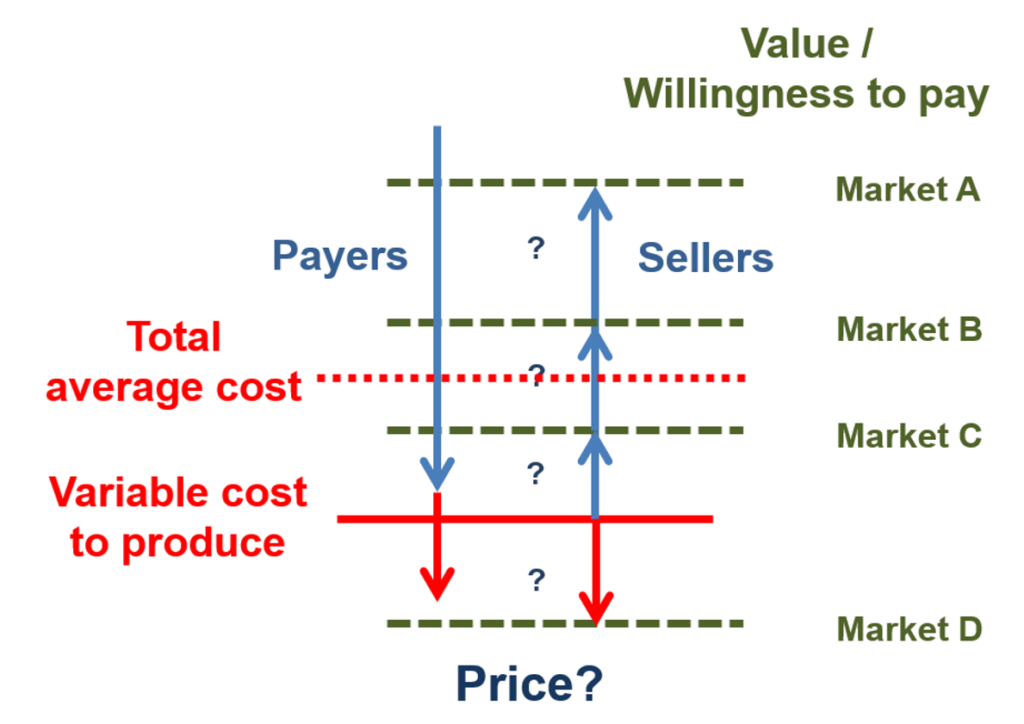

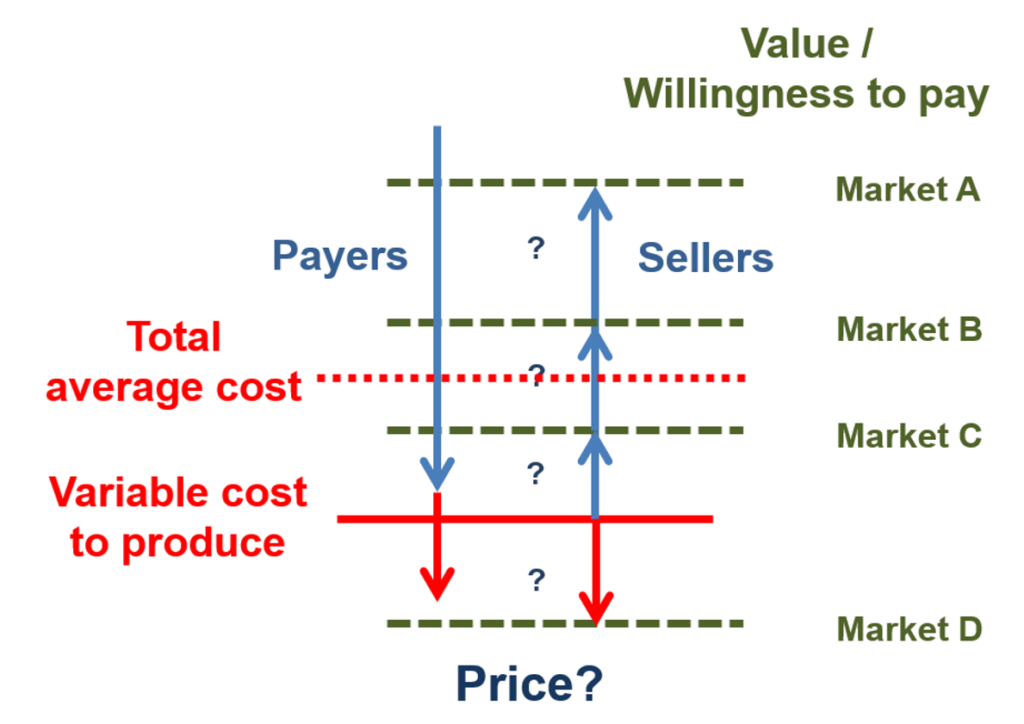

Figure 1 builds on this point. Development costs, including the costs of failures, are fixed costs. As such, they do not show up in the average variable costs required to produce and support a drug and its associated services in the market. The high relevance of fixed costs creates a substantial gap between “Variable cost to produce” and “Total average cost”, as the horizontal red lines in the figure depict.

Figure 1. Bio-pharma value, costs, and prices

The gap between variable costs and average total costs introduces a major issue in bio-pharma price negotiations. The goal of a pharmaceutical firms’ negotiator is to gain a price as close as possible to a buyer’s value ceiling (the horizontal green dashes in the figure). Yet few buyers will simply pay for the full value they receive from any product – including products that produce health value – if they can negotiate a lower price.

Instead, the goal of any payer is to negotiate price down as close as possible to its estimate of the seller’s average variable cost. That is the minimum price below which a producer cannot cover its operating expenses. And, if pushed to the limit, the variable cost floor is the price that a seller will settle for: this rate at least covers the costs of producing and selling the drug. Where the price ends – up near the value ceiling or down on the variable cost floor – depends on the comparative bargaining power and negotiation skill of the buyer and seller.

This is a challenging negotiating calculus. All payers in the health sector face real pressure on their budgets, with increased prices for pharmaceutical products creating part of those pressures. In the U.S., prescription pharmaceuticals accounted for almost $325 billion in 2015, about 10.1% of national health expenditures (up from 8.8% in 2000), behind the hospital (32%) and physician/clinical (20%) shares. [8] In Canada, drug expenditures reached about 16.2% of national health expenditures in 2016, behind only hospitals (29%), up slightly from 15.4% in 2000. [9] Hence, even though a payer may recognize and even embrace the high health value ceiling of a pharma product, it needs to push as hard as possible to bring prices down toward the variable cost floor.

The individual buyer’s goal to push prices to the floor in turn creates the rub for the seller. If every payer successfully negotiated a price that just met a drug’s average variable cost, then the company producing the drug would fail because it was not covering its fixed costs of development. Instead, a bio-pharma firm requires some degree of negotiating power to charge at least some buyers prices that exceed the minimum market clearing price, shifting up toward the value ceiling.

Indeed, this is one of the purposes of the patent system: to provide a successful innovator with a period of exclusivity in which it can recover the costs of creating the innovation. Then, once a patent ends or, equally powerfully, once a product with similar therapeutic value enters the market, competition will drive prices down toward marginal costs. This balance – of incentive to innovate and competition to bring on subsequent price pressure – is central to patent policy and law.

Now let’s use Figure 1 to make things a bit more complicated, while introducing a necessary part of pharmaceutical pricing strategy. The bio-pharma market, like almost all markets, has multiple segments, with different customers who have differing ability and willingness to pay for a product. In Figure 1, these segments are depicted as Markets A, B, C, and D. For a pharmaceutical company, the goal is to identify the combination of value and ability to pay for each segment and, ideally, settle on prices that come close to that value ceiling for each market, while surpassing variable costs. Such price discrimination strategies are profit maximizing.

Market segmentation introduces pricing variation across and within countries. For instance, prices are commonly lower in lower income countries such as Greece and Spain, versus higher prices in higher income countries such as Germany and the U.S. Even within countries, different payers commonly have different ability to pay. In the U.S., for example, the state-based Medicaid systems are mandated to receive the lowest price negotiated by any other actor, while other payers such as employment-based PBMs commonly have greater latitude and financial resources.

In such cases of multiple market segments with different ability to pay, a pharma company’s dominant strategy is to set different pricing points for each segment. To be sustainable, the strategy needs to result in some prices being high enough above the variable cost floor, in aggregate across the company’s portfolio of products, to cover the gap between that floor and total average costs.

Market D in Figure 1, where buyers are not able or willing to pay enough to cover even the variable costs of production, introduces a further complication. In most industries, sellers would ignore this segment. Yet in healthcare markets, most people – including most people who work in pharmaceutical companies – feel a responsibility to reach as many patients as possible, including those who cannot pay enough to cover operating costs. While no public or private actor can afford infinite below cost contributions, there is real need and desire to provide access to as much of the population as possible. For pharma companies, this is part of the basis of patient assistance programs, which provide subsidized or free drugs and services when people in market D lack insurance or personal resources. In turn, though, such below cost strategies place even more pressure to move well above the variable cost floor when negotiating with buyers in market segments A, B, and C.

Quite simply, “too much” pressure to drive prices down will lead to two negative consequences. In the short term, the pressure will drive out a company’s ability to provide cross-subsidized services below the variable cost floor. In the longer term, the pressure will drive innovative firms out of the market because they cannot cover the gap between variable and total costs.

Time windows before competitors enter have become shorter

Now consider time windows for pharmaceutical companies to earn high prices, even after discounts. The key issue here is penetration of the market by generic drugs and “biosimilars” of biologics. Before the 1984 Hatch-Waxman legislation facilitated entry of generic competitors when drugs came off patent, generic drugs made up about 20% of prescriptions in the U.S. Generic penetration grew to about 40% in 2000. Today, as generic and biosimilar competition has become much more active, and as payers respond to pricing pressure by mandating generics on formularies whenever possible, the generic prescription rate in the U.S. is about 90%. Most traditional developed markets also are at substantial, if somewhat lower, levels; Canada, for instance, has a generic prescription rate of about 70%.

Moreover, under the rules of Hatch-Waxman and similar policies around the world, generic approvals have grown exponentially. In 1984, the U.S. FDA reported 66 approvals; in 2017, there were 847 generic approvals. [10] Generic competitors are commonly lined up to enter the market immediately when a drug goes off patent, particularly if the drug had achieved a substantial market size.

Once generic competitors enter, prices fall, sometimes drastically. Prices for traditional large market drugs with multiple generic competitors commonly face price reductions of as much as 90%. Price reductions for the specialized biologicals that have begun to go off patent and face biosimilar competition have been less striking, because so far there are fewer competitors. Nonetheless, the reductions are substantial, with discounting in the range of 35% commonly being reported.

Once generic competition becomes active, prices move, often rapidly, toward the variable cost floor in Figure 1. From the point of view of payers, this is a good outcome. And, again, this is one of the goals of the patent system: provide a period of exclusivity as an incentive to innovate, then open the doors to competition to create incentives to innovate again as well as providing cost effectiveness in the market.

From the point of view of a bio-pharma innovator, though, this increasingly striking combination of early generic entry and strong price reductions means that there are far fewer years than there once were to earn the profits needed to cover the gap between variable and fixed costs. If the firm is going to survive, it needs active strategies to deal with the shorter window.

Time window strategies have had two major components, both of which we have noted earlier. First, companies are increasingly emphasizing specialty drugs. This is partly a feature of the biological revolution, which has created opportunities for major contributions to health for targeted medical needs. In addition, drugs for specialty market segments such as oncology and immunology, whether based on biological or older science, typically face lower rates of post-patent generic competition, both because only a few firms currently have the skills needed to compete effectively and because specialty prescribers and patients are often reluctant to switch away from drugs that they have come to understand and rely on. Hence, even after patents expire, specialty drugs commonly achieve prices above the variable cost floor, sometimes for multiple years.

Second, firms have increased the initial prices they charge during the shorter protected window, in order to generate income as quickly as possible before facing generic or biosimilar competition. Thus, the policy changes that have encouraged price competition from generics – as desirable as these policies undoubtedly are for payers, patients, and the health system – have also created strong pressures to increase prices that policy makers are now complaining about. The quid of competition and long term price reductions has induced a pro quo of initial price increases.

Where does this leave us?

The key question is whether healthcare systems in countries such as the U.S. are now reasonably close to achieving a balance of innovation and cost effectiveness or, as some voices implicitly claim, can we continue to maintain incentives to innovate while drastically bringing down pre-generic prices? My interpretation of the data and observation of strategies and incentives is that we are fortunate to have an actively innovative bio-pharma sector, made up of a complex and dynamic mix of established firms, new ventures, academic and government scientists, complementary firms, and regulatory bodies, paralleled by a critically important set of generic manufacturers (some of which are the same companies) that help provide discipline in the system. This quasi-market is far from fully efficient – no market is – but it has evolved to a point of generating and commercializing new bio-pharmaceutical products and supporting services at a rate that is higher than at any point in the history of the industry.

Consider recent innovation. Just as approval of generics is increasing, so is approval of new drugs. In 2017, the U.S. FDA reported granting 54 new approvals, including 21 biologicals. This was the highest rate ever (other than a 1996 clean out of the approval pipeline), up from 29 (2 biologicals) in 2000. The companies that received the approvals included a wide mix of established pharmaceutical firms from Western Europe, Japan, and the U.S., plus an even wider mix of new ventures and smaller specialty companies.

Now consider market entry. Innovator companies commonly apply for FDA approval and introduce their drugs to the U.S. market before entering other countries. The prices available in the U.S. are not as much higher than those in other traditional developed markets as reported list prices would suggest, but on average are somewhat higher, due in large part to the multiple segments available for price discrimination. In turn, profitability in the U.S. is higher: the few firms that report geographic profit margins commonly recognize operating profits as a percentage of sales that are 15% to 25% higher in the U.S than in Europe. Higher prices and profits typically lead to faster entry, earlier access to novel treatments, and ultimately, earlier access to lower-priced generics once the innovators’ patents expire.

It is important to recognize that there are outliers in the system. Some companies earn very high profits, though typically for only a few years. In part, the hope of such profits can be viewed as a lottery that incents entry to the industry. Indeed, there are far more companies with very negative profitability than very positive results – the median return on sales of all bio-pharma companies in the Compustat data base (now more than 500 firms) has been negative each year since 1989. The lure of a payoff is a necessary complement to the uncertainties of experimentation.

There are also outliers in pricing strategy that on the face, and likely even the depths, of it do appear unreasonable. Massive increases in prices of sole-source generic drugs that can be maintained until competitors gain approval and enter, which typically takes several years, stick in many craws. But it is important to recognize that these are outliers and not to develop general policies targeted at extreme cases.

A key point here is that it is equally important to recognize that lower prices typically lead to later entry and sometimes no entry at all. Introduction rates to lower priced southern European markets, for instance, are substantially lower than in North America or much of northern Europe. Simply forcing prices to a lower level in any given country, whether the U.S. or elsewhere, would almost certainly lead to reduced entry in that country.

Nonetheless, there is an active policy and health question here, of when higher initial prices in a market – and consequent more active entry – are balanced by greater health benefits. The answer to that question requires engagement of multiple stakeholders in the health system, including payers, prescribers, regulators, bio-pharma companies, and patients. Currently, once a drug has received market approval, payers such as PBMs have become increasingly powerful gate keepers in access, with their role in setting formularies. There is real strength in that role, but there are also opportunities for more effective engagement of the other stakeholders in assessing costs and benefits.

If there is a need for policy initiatives, the goal of integrating insights across the fragmented silos of the healthcare system in the U.S. and elsewhere is far more of a priority than the marginal reductions in prices that could be accomplished without drastically damaging the ability of innovator companies and their generic followers to provide continuing health value. Rather than the current debate about costs, we would be much better served by a debate – and action – about appropriate value.

References

- Daniel C. Morgan, and Samuel E. Allison. 1964. The Kefauver Drug Hearings in Perspective. Southwestern Social Science Quarterly, 45 (1): pp. 59-68. https://news.gallup.com/poll/12748/business-industry-sector-ratings.aspx

- William S. Comanor. 1966. The Drug Industry and Medical Research: The Economics of the Kefauver Committee Investigations, The Journal of Business, 39 (1): pp. 12-18. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2352011?seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents

- Yasmeen Abutaleb and Michael Erman. 2018. Trump seeks to base Medicare drug prices on lower overseas rates. Health News, October 25. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-trump-drugpricing/trump-seeks-to-base-medicare-drug-prices-on-lower-overseas-rates-idUSKCN1MZ2SF

- https://news.gallup.com/poll/12748/business-industry-sector-ratings.aspx

- As one of many examples of studies of health benefits, see a discussion of health benefits for rheumatoid arthritis see: John J. Cush and Kathryn H. Dao. 2007. Perspectives on Safety vs. Benefits of Biologic Therapies. Medscape Rheumatology. https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/553515_4

- Robert S. Kaplan, Michael E. Porter, Mark L. Frigo. 2017. Managing Healthcare Costs and Value. Strategic Finance 98 (no. 7): pp. 24–33.

- Cole Werble. 2017. “Health Policy Brief: Pharmacy Benefit Managers,” Health Affairs, September 14, 2017. DOI: 10.1377/hpb20170914.000178

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI): https://apps.cihi.ca/mstrapp/asp/Main.aspx

- Drugs@FDA: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Reports.NewOriginal_ANDA